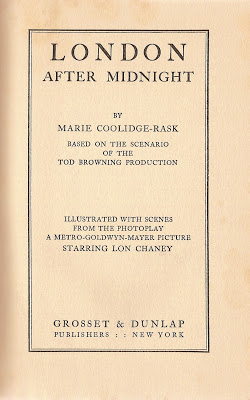

Here begins a chapter-by chapter synopsis of London After Midnight, a novel by Marie Collidge-Rask, based on the scenario of the Tod Browning production. Like the book, the synopsis will be

Balfour House is an old ancestral home on the outskirts of London whose origins stretch back to before the time of Charles II. Successive generations of the Balfour family have added to it until it is a weird and mystifying architectural abnormality, a labyrinth of chambers, corridors, passageways and dark, massively furnished and heavily curtained rooms. One room, heavily bolted and padlocked, has not been opened in centuries. It is said that a beautiful young woman once met a horrible death in that room, and that her ghost walks restlessly moaning and sobbing whenever some tragedy is about to occur in the house. Those sobs are heard the night Roger Balfour is found dead in the house, a bullet in his head, driven to suicide by depression and money problems.

Roger’s son Harry, 15, and daughter Lucy, 13, become the wards of their father’s friend and neighbor Sir James Hamlin. Since there was no will, Sir James supervises the settling of Roger Balfour’s estate and takes the two children into his home. Balfour House and its grounds become shunned and neglected and, with no money left for their upkeep after settling Roger’s debts, fall into disrepair.

Five years pass. Harry Balfour, now 20 and more than a little resentful of his and Lucy’s dependence on Sir James’s generosity, returns from school and announces that he wants to reopen Balfour House. Sir James says this is impossible without major repairs, either by finding a wealthy tenant or a wealthy bride for Harry. Harry refuses to marry for money. Sir James offers to buy the Balfour estate outright, to give Harry a stake in life. Again, Harry indignantly refuses: “So long as I live the Balfour estate shall not revert to other hands.”

Soon after this, Harry has an unpleasant scene with Jerry Hibbs, Sir James’s secretary. An agitated Hibbs mutters to himself that Harry is “courting disaster” if he goes near Balfour House.

Two days after his confrontations with Sir James and Hibbs, Harry fails to show up for a riding date with his sister Lucy. No one has seen him since dinner the night before, and his bed has not been slept in. At first Lucy pouts that Harry has ruined her day, but as the day wears on she begins to worry.

That night Hibbs sends one of the servants on a confidential errand. Overheard by the maid, Anna Smithson, Hibbs asks her to say nothing to anyone.

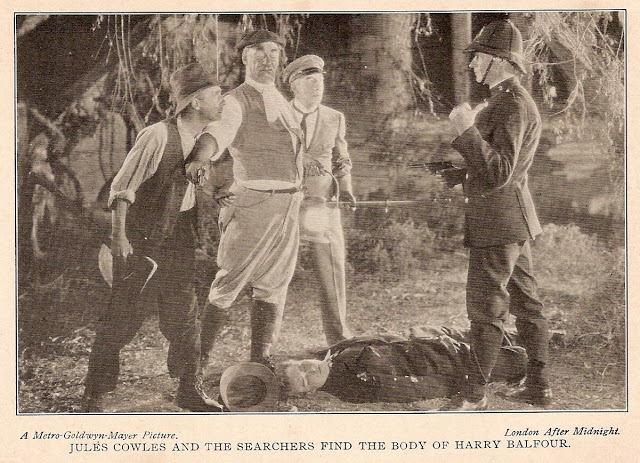

An hour later a group of Sir James’s servants, lashed by wind and rain, spooked and unnerved as they search through the overgrown grounds at Balfour House, find the body of Harry Balfour. As they lift the body to carry it to shelter, one of the servants swears he can hear, beneath the whistling of the wind, the wails of the ghost in the secret room of Balfour House.

Chapter 3 – Who Killed Harry Balfour?

Lucy Balfour is still worrying about Harry’s disappearance when her brother’s body is brought in. She is distraught at his death and horrified, as are the others, at the sight of two red wounds on his throat. The coroner’s inquest returns a verdict of death at the hands of “person or persons unknown.” In testimony at the inquest, neither Sir James nor Hibbs mentions their respective run-ins with Harry before his disappearance. The maid Smithson testifies that on the night of the murder, she was looking out a window into the storm and saw a man heading toward Balfour House. The man was definitely not Master Harry, she says. It is assumed that the person she saw was the murderer, but there is no clue as to his identity, his motive, or why he would make those wounds on Harry’s throat.

Chief Detective Inspector Burke of Scotland Yard, dining with the assistant commissioner of his division, discusses the unsolved murder of Harry Balfour. Burke believes that the murder of Harry confirms his suspicion that Roger Balfour was murdered as well, even though all signs seemed to point to suicide at the time. He says that he has a number of leads but no firm evidence, and plans to test his theory that under hypnosis and the proper conditions, a criminal will reenact his crimes. Burke borrows a book from the assistant commissioner’s library, saying that he expects to be busy with his investigation for some time, but when next they dine together, Burke says, he is sure he’ll have the proof he needs.

Seven months have passed since Harry’s death, and Lucy is finally beginning to emerge from her grief. As May turns to June, Lucy finds herself turning more and more to Jerry Hibbs for companionship, and her feelings for him have grown more than sisterly. At last, in a sun-bathed arbor scented by the blooming roses of Hamlin House, Lucy and Hibbs profess their love for one another. They agree to say nothing to Sir James for the time being, for fear that he will disapprove and dispense with Hibbs’s services.

Chapter 6 – Uncanny Tenants

Night. Two men stand under a tree on the grounds of Balfour House, near where Harry Balfour’s body was discovered. They are representatives of the London realtor’s office that administers the Balfour property and are waiting while prospective tenants inspect the premises by lantern-light. The people came into the office near closing time and expressed an interest after seeing a picture of the house in a magazine (the realtors having long since given up advertising the property). If satisfactory, the tenants propose to move in at once. This has all happened so quickly that the agent hasn’t had time to notify Sir James, though he did get in touch with Hibbs. Hibbs told him to go ahead with the transaction if the tenants’ references are satisfactory. The agent is waiting outside for the tenants because, he said, nothing would induce him to enter the house.

Meanwhile, Anna Smithson and Thomas, another of the Hamlin House servants, are returning from the village station in a cart with the luggage of a guest Sir James is expecting. They see the light in Balfour House. They can see two shadowy figures moving about with the lantern; one of them is a woman, but they can make out no other details. Thomas believes the woman is the ghost of the house, but Anna scoffs. As they watch, the door of Balfour House opens and a man emerges, tall but stooped, shrouded in a heavy Inverness coat and wearing a high beaver hat. That’s all it takes for Thomas to crack his whip and hurry the horse on to Hamlin House.

At Hamlin House, preparations are under way for the coming of Colonel Yates, Sir James’s guest, when the realtor’s agents arrive. Sir James is astonished to learn that Balfour House has been let, and it is evident that the surprise is not an entirely pleasant one. Hibbs explains that he did not expect the tenants to take immediate possession; he thought they would merely inspect the property and then negotiate terms. The agents report that the tenant’s references were impeccable and he paid the entire term of the lease in cash, in advance.

Reassured, Sir James glances at the papers the agents have handed him. His calm demeanor vanishes and his face goes white when he sees the signature on the lease. It is signed “Roger Balfour.” And it is in Roger Balfour’s handwriting.

Why wasn’t this noticed at the office? Sir James asks. The agent replies that the matter was handled by a new employee who didn’t know the house’s history; the agent himself had simply presumed that this Roger Balfour was perhaps a distant relation wishing to see the ancestral home. Sir James says there are no other branches of the family and demands a description of the man in the beaver hat.

At this point, the butler announces Colonel Yates. Sir James’s consternation is almost complete, because in addition to this shock about Roger Balfour, he has been trying all day to remember who Colonel Yates is; he learned only today that this “old friend from India” was coming, and has been unable to place the name. As Yates is ushered in, however, Sir James remembers him at once and is reassured by Yates’s solid, dependable, no-nonsense presence. In fact, he welcomes his guest’s opinions on the matter of the new tenant at Balfour House, and briefly explains the situation to him.

It turns out Yates had known Roger Balfour years before, but had lost touch and did not know of his death; he says suicide seems unlike the Balfour he knew. When the agents describe the new tenant as “creepy” and “un-holy,” Yates scoffs. “You chaps must have been smoking something…” His laughter diffuses the tension in the room; even Sir James looks less upset.

As Yates and Sir James discuss the matter later, alone, Sir James shows Yates some documents signed by the late Roger Balfour, and Yates concedes that the handwriting on the lease is unmistakeably the same. Mulling this over, he cautions Sir James not to dismiss out of hand the idea of supernatural; years in India, he says, have taught him the folly of that. In fact, he has a book with him that he thinks might bear on the subject, and promises to give it to Sir James. Later, after dressing for dinner, Yates gives the book to Hibbs to place in the library, where it will be available to anyone interested. Hibbs (who for some reason has taken an instant, mild dislike to Colonel Yates) does so, and a glance at the book’s contents interests him enough to make him resolve to come back to it later.

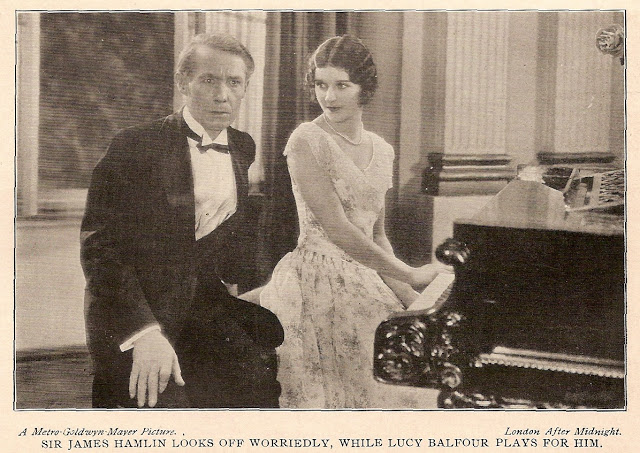

All through dinner, and even afterward as Lucy plays for diversion, Sir James’s mind is elsewhere. He had insistd to Yates that he does not believe in ghosts, but he nevertheless has a superstitious nature and is troubled.

All through dinner, and even afterward as Lucy plays for diversion, Sir James’s mind is elsewhere. He had insistd to Yates that he does not believe in ghosts, but he nevertheless has a superstitious nature and is troubled.

Here’s another look at those eyes, this time smoldering and looking straight into your own. The portrait is by the German painter Friedrich August von Kaulbach (1850-1920), and is now part of the Geraldine Farrar Collection in the Music Division of the Library of Congress. It was probably painted in late 1901 or early ’02, about the time the 19-year-old Geraldine created a sensation as Marguerite in Gounod’s Faust and became the toast of Berlin.

Here’s another look at those eyes, this time smoldering and looking straight into your own. The portrait is by the German painter Friedrich August von Kaulbach (1850-1920), and is now part of the Geraldine Farrar Collection in the Music Division of the Library of Congress. It was probably painted in late 1901 or early ’02, about the time the 19-year-old Geraldine created a sensation as Marguerite in Gounod’s Faust and became the toast of Berlin.

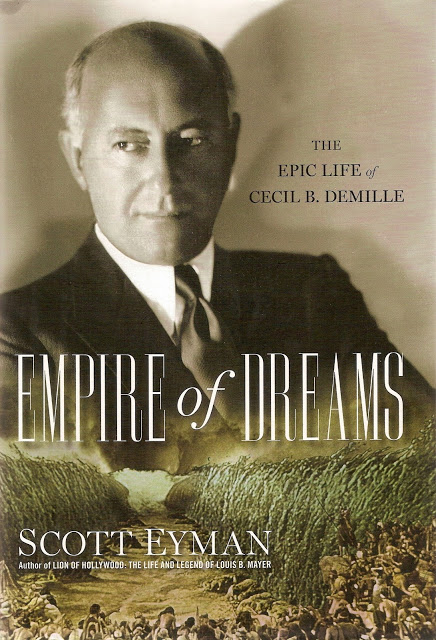

And here she is again, assuring her gypsy confederate (Horace B. Carpenter) that the trap is ready to be sprung. As DeMille biographer Scott Eyman observes, Farrar wasn’t exactly beautiful, but she was alluring. Her Carmen moves like a cat, slinky, self-assured and radiating a confident, even aggressive sexuality. (Apparently in real life, too; Crown Prince Wilhelm wasn’t the only name linked romantically with hers. While at the Met she carried on a torrid six-year affair with conductor Arturo Toscanini that ended only when she gave him an ultimatum: leave your wife or else. The maestro abruptly resigned from the Met and beat a hasty retreat back to Italy, wife and family in tow.)

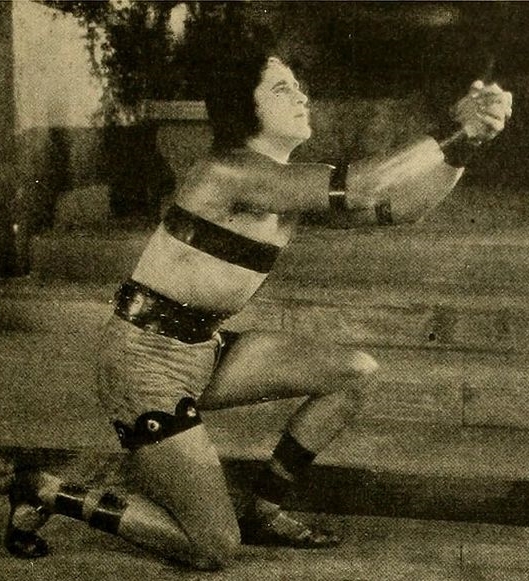

And here she is again, assuring her gypsy confederate (Horace B. Carpenter) that the trap is ready to be sprung. As DeMille biographer Scott Eyman observes, Farrar wasn’t exactly beautiful, but she was alluring. Her Carmen moves like a cat, slinky, self-assured and radiating a confident, even aggressive sexuality. (Apparently in real life, too; Crown Prince Wilhelm wasn’t the only name linked romantically with hers. While at the Met she carried on a torrid six-year affair with conductor Arturo Toscanini that ended only when she gave him an ultimatum: leave your wife or else. The maestro abruptly resigned from the Met and beat a hasty retreat back to Italy, wife and family in tow.) The Woman God Forgot wasn’t released until 1917; the big money picture for ’16 was Joan the Woman. DeMille and Macpherson drew a direct parallel between the Hundred Years War and the war then raging in Europe, telling the story of Joan’s battle for France within a framing story of an English officer in the trenches of the Great War (also played by Wallace Reid) who takes heart from Joan’s devotion (and attains a similar shall-not-have-died-in-vain martyrdom under the barbed wire). This publicity still was presumably approved for release by DeMille and Lasky, but unfortunately it isn’t terribly becoming to Ms. Farrar; granted, she was some years over-age (and some pounds overweight) for the role, but in the finished picture she never looks quite as tomboy-silly as she does here.

The Woman God Forgot wasn’t released until 1917; the big money picture for ’16 was Joan the Woman. DeMille and Macpherson drew a direct parallel between the Hundred Years War and the war then raging in Europe, telling the story of Joan’s battle for France within a framing story of an English officer in the trenches of the Great War (also played by Wallace Reid) who takes heart from Joan’s devotion (and attains a similar shall-not-have-died-in-vain martyrdom under the barbed wire). This publicity still was presumably approved for release by DeMille and Lasky, but unfortunately it isn’t terribly becoming to Ms. Farrar; granted, she was some years over-age (and some pounds overweight) for the role, but in the finished picture she never looks quite as tomboy-silly as she does here.

Alas, the honeymoon with Lasky and DeMille did not last, chiefly because of the honeymoon with Lou Tellegen. The Dutch-born Tellegen had come to America in 1910 at 29, as leading man (and offstage consort) to Sarah Bernhardt. After marrying Farrar in 1916, when she returned to Hollywood he began throwing his weight around and interfering in her films. To keep him out of their hair (and hers), DeMille and Lasky allowed him to direct a picture, What Money Can’t Buy. When they judged that one to be a dog — along with another, The Things We Love — Tellegen got his nose bent out of shape, and Farrar (out of what she later ruefully called “wifely loyalty”) sided with him. Both of them left the Lasky Co. and signed with Samuel Goldwyn.

Alas, the honeymoon with Lasky and DeMille did not last, chiefly because of the honeymoon with Lou Tellegen. The Dutch-born Tellegen had come to America in 1910 at 29, as leading man (and offstage consort) to Sarah Bernhardt. After marrying Farrar in 1916, when she returned to Hollywood he began throwing his weight around and interfering in her films. To keep him out of their hair (and hers), DeMille and Lasky allowed him to direct a picture, What Money Can’t Buy. When they judged that one to be a dog — along with another, The Things We Love — Tellegen got his nose bent out of shape, and Farrar (out of what she later ruefully called “wifely loyalty”) sided with him. Both of them left the Lasky Co. and signed with Samuel Goldwyn. What might have been if Geraldine Farrar had not joined in Lou Tellegen’s falling-out with Cecil B. DeMille is a tantalizing question mark. Even more tantalizing is the thought of how her career might have gone if she’d been born 20 years later, if she had made that hit in Berlin in 1921 instead of 1901. Then, when Hollywood went ransacking New York for musical talent during the sound revolution, she would have been about the age she is here, when she created the role of the Goose-Girl in Humperdinck’s Königskinder (The King’s Children) at the Met in 1910. Jeanette MacDonald and Irene Dunne, among others, may have had reason to be grateful that they never had to deal with any competition frrom Geraldine Farrar.

What might have been if Geraldine Farrar had not joined in Lou Tellegen’s falling-out with Cecil B. DeMille is a tantalizing question mark. Even more tantalizing is the thought of how her career might have gone if she’d been born 20 years later, if she had made that hit in Berlin in 1921 instead of 1901. Then, when Hollywood went ransacking New York for musical talent during the sound revolution, she would have been about the age she is here, when she created the role of the Goose-Girl in Humperdinck’s Königskinder (The King’s Children) at the Met in 1910. Jeanette MacDonald and Irene Dunne, among others, may have had reason to be grateful that they never had to deal with any competition frrom Geraldine Farrar.

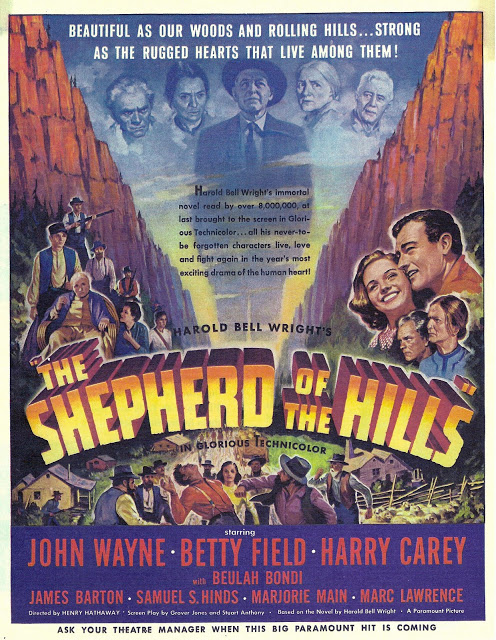

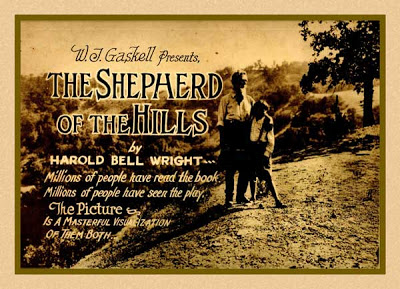

The best of the lot just may be Betty Field in Shepherd. Her Sammy is feisty and independent, uneducated and superstitious — muttering half-heard incantations, drawing symbols and spitting in the dirt before venturing into Moaning Meadow — but no fool. She knows her own world inside out, and when her moonshiner father stumbles home with a revenuer’s bullet in his side, she calmly goes about her business, slicing bacon and singing as if nothing had happened, until the suspicious lawmen have gone their way. When she meets Daniel Howitt, she’s wary at first, but she soon sees the good in the man and vouches for him to others; when he seeks to cash a check for the unheard-of sum of a hundred dollars, the storekeeper blanches, but says, “Sammy’s say-so is all right with me. I’ll look around.” Sammy senses the tender heart of Young Matt, too, and struggles to reach it, battering in futile frustration at the crust of hatred so carefully planted and tended by the malicious Aunt Mollie.

The best of the lot just may be Betty Field in Shepherd. Her Sammy is feisty and independent, uneducated and superstitious — muttering half-heard incantations, drawing symbols and spitting in the dirt before venturing into Moaning Meadow — but no fool. She knows her own world inside out, and when her moonshiner father stumbles home with a revenuer’s bullet in his side, she calmly goes about her business, slicing bacon and singing as if nothing had happened, until the suspicious lawmen have gone their way. When she meets Daniel Howitt, she’s wary at first, but she soon sees the good in the man and vouches for him to others; when he seeks to cash a check for the unheard-of sum of a hundred dollars, the storekeeper blanches, but says, “Sammy’s say-so is all right with me. I’ll look around.” Sammy senses the tender heart of Young Matt, too, and struggles to reach it, battering in futile frustration at the crust of hatred so carefully planted and tended by the malicious Aunt Mollie.

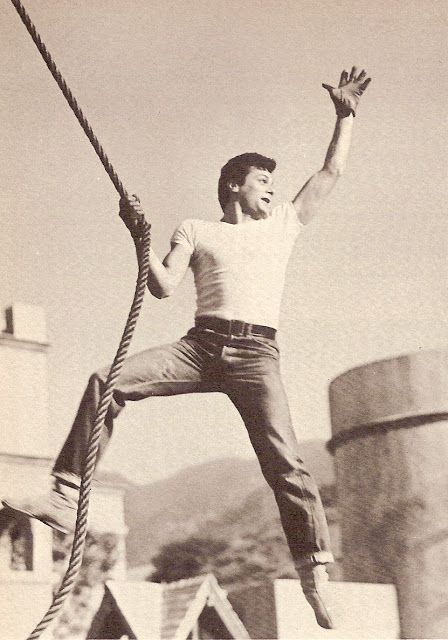

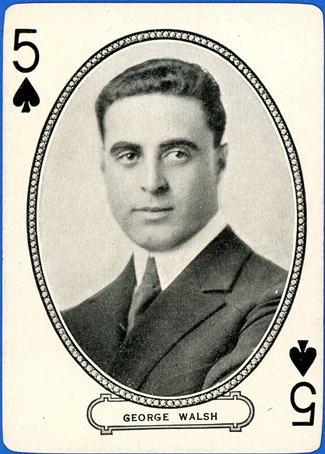

But back to our subject. Born in 1889, George Frederick Walsh followed his older brother Raoul (né Albert Edward) into pictures in the mid-1910s, having originally planned to be an attorney (he attended, however briefly, Fordham and Georgetown). He also attended New York’s High School of Commerce, where he graduated in 1911, and where he was a versatile athlete: baseball, track, cross country, swimming, rowing. This experience would stand him in good stead, at least in the Hollywood short run — certainly better than whatever he learned about commerce or pre-law.

But back to our subject. Born in 1889, George Frederick Walsh followed his older brother Raoul (né Albert Edward) into pictures in the mid-1910s, having originally planned to be an attorney (he attended, however briefly, Fordham and Georgetown). He also attended New York’s High School of Commerce, where he graduated in 1911, and where he was a versatile athlete: baseball, track, cross country, swimming, rowing. This experience would stand him in good stead, at least in the Hollywood short run — certainly better than whatever he learned about commerce or pre-law. George did get his first breaks in Reliance-Mutual pictures directed by Raoul and others, moving up the cast list till he was top-billed, and first drawing the eye of Variety’s reviewer in Raoul’s Blue Blood and Red (1916): “The kid is clever…a fine, manly looking chap, full of athletic stunts…” By this time, both Raoul and George were working for William Fox, and soon George worked again for D.W. Griffith. Here he is as the Bridegroom of Cana in the Judean Story section of Intolerance, receiving the bad news that the wine supply has run out. With him are 17-year-old Bessie Love (still several years from her own stardom) as the Bride of Cana and William Brown as the father of the bride.

George did get his first breaks in Reliance-Mutual pictures directed by Raoul and others, moving up the cast list till he was top-billed, and first drawing the eye of Variety’s reviewer in Raoul’s Blue Blood and Red (1916): “The kid is clever…a fine, manly looking chap, full of athletic stunts…” By this time, both Raoul and George were working for William Fox, and soon George worked again for D.W. Griffith. Here he is as the Bridegroom of Cana in the Judean Story section of Intolerance, receiving the bad news that the wine supply has run out. With him are 17-year-old Bessie Love (still several years from her own stardom) as the Bride of Cana and William Brown as the father of the bride. “Walsh is in his glory scaling walls, climbing trees, foiling cops, etc. There are a couple of corking fights where he handles anywhere from a dozen to twenty opponents at a time”; From Now On (’20), “What may be held up for approval is the hard work which George Walsh invests in it.” The image conjured up from these reviews is a series of lightweight adventures distinguished by George’s prowess; as brother Raoul, who directed From Now On, said years later, “Well, anything with him wouldn’t be too heavy.”

“Walsh is in his glory scaling walls, climbing trees, foiling cops, etc. There are a couple of corking fights where he handles anywhere from a dozen to twenty opponents at a time”; From Now On (’20), “What may be held up for approval is the hard work which George Walsh invests in it.” The image conjured up from these reviews is a series of lightweight adventures distinguished by George’s prowess; as brother Raoul, who directed From Now On, said years later, “Well, anything with him wouldn’t be too heavy.” Then came what looked like the break of a lifetime: George Walsh was chosen by writer June Mathis to play the title role in Metro’s screen adaptation of Ben-Hur, to be shot on location in Rome. The role was coveted by every actor in movies except Jackie Coogan. The most popular choice, Rudolph Valentino, was out of play because of a contract dispute with Famous Players-Lasky; until they settled their differences, the studio wasn’t about to let him work for anyone else. Mathis ordered tests, dozens of them, and Walsh won out. In his recounting of the Ben-Hur production in

Then came what looked like the break of a lifetime: George Walsh was chosen by writer June Mathis to play the title role in Metro’s screen adaptation of Ben-Hur, to be shot on location in Rome. The role was coveted by every actor in movies except Jackie Coogan. The most popular choice, Rudolph Valentino, was out of play because of a contract dispute with Famous Players-Lasky; until they settled their differences, the studio wasn’t about to let him work for anyone else. Mathis ordered tests, dozens of them, and Walsh won out. In his recounting of the Ben-Hur production in

And so did Charlotte. Somebody made up a nursery rhyme:

And so did Charlotte. Somebody made up a nursery rhyme:

He may have had other effects on her as well, and that possibility came to light only after the evening of Wednesday, February 1, 1922. On that night, sometime after 7:45 p.m., in the living room of this bungalow at 404-B Alvarado Street in Los Angeles, somebody stood behind William Desmond Taylor and shot him dead with a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson revolver.

He may have had other effects on her as well, and that possibility came to light only after the evening of Wednesday, February 1, 1922. On that night, sometime after 7:45 p.m., in the living room of this bungalow at 404-B Alvarado Street in Los Angeles, somebody stood behind William Desmond Taylor and shot him dead with a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson revolver.

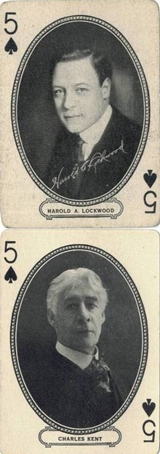

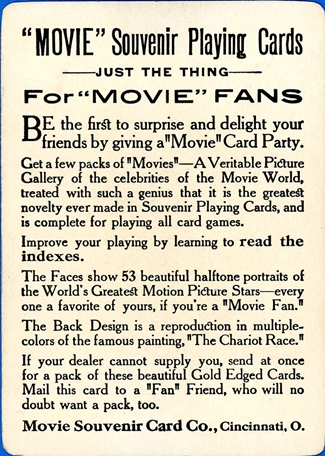

Try to imagine a time when a deck of cards with movie star pictures was a novelty. It’s not easy, is it? We can hardly even imagine a time when a movie star was such a novelty that the word “movie” itself was in quotes. But here it is, courtesy of one M.J. Moriarty and the Movie Souvenir Card Co. of Cincinnati, Ohio.

Try to imagine a time when a deck of cards with movie star pictures was a novelty. It’s not easy, is it? We can hardly even imagine a time when a movie star was such a novelty that the word “movie” itself was in quotes. But here it is, courtesy of one M.J. Moriarty and the Movie Souvenir Card Co. of Cincinnati, Ohio.

Von Wagner painted at least three versions of the painting, the first one in 1873 for the Vienna Exposition. A second version went on display at Philadelphia’s Centennial Exposition in 1876, and another — or perhaps the same one — at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The painting sparked a national craze, with etchings and lithograph prints for sale everywhere. Contrary to what some have said, it does not reproduce a scene from Ben-Hur, which wasn’t published until 1880; indeed, the painting and its pop-culture clones may have inspired Gen. Lew Wallace to include such a scene in his novel. In point of fact, the full title of the work is “Chariot Race in the Circus Maximus, Rome, in the Presence of the Emperor Domitian”, which would have been several decades after Judah Ben-Hur and Messala had their fateful showdown in Antioch’s Circus Maximus. Only one of von Wagner’s versions of the painting is known to survive; it hangs today in the Manchester Art Gallery in England.

Von Wagner painted at least three versions of the painting, the first one in 1873 for the Vienna Exposition. A second version went on display at Philadelphia’s Centennial Exposition in 1876, and another — or perhaps the same one — at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The painting sparked a national craze, with etchings and lithograph prints for sale everywhere. Contrary to what some have said, it does not reproduce a scene from Ben-Hur, which wasn’t published until 1880; indeed, the painting and its pop-culture clones may have inspired Gen. Lew Wallace to include such a scene in his novel. In point of fact, the full title of the work is “Chariot Race in the Circus Maximus, Rome, in the Presence of the Emperor Domitian”, which would have been several decades after Judah Ben-Hur and Messala had their fateful showdown in Antioch’s Circus Maximus. Only one of von Wagner’s versions of the painting is known to survive; it hangs today in the Manchester Art Gallery in England.

In 1937, Capra gave Warner the opportunity to deliver probably his best screen performance. The picture was Lost Horizon, from James Hilton’s utopian romance about a group of refugees from war-torn “civilization” who find themselves in the remote Himalayan paradise of Shangri-La. Warner (here with Isabel Jewell, Edward Everett Horton, Ronald Colman and Thomas Mitchell) played Chang, their mysterious escort from the snowbound wreck of their plane to the Edenic Valley of the Blue Moon, and their host after they arrive. Endlessly cordial, welcoming and polite, he nevertheless is inscrutably vague about when and how they will ever be able to return to their homes. Warner got an Oscar nomination as best supporting actor, but he didn’t win; he lost out to Joseph Schildkraut as Alfred Dreyfus in Warner Bros.’ The Life of Emile Zola. That’s a worthy performance, but I’m not at all sure the Academy made the right call. H.B. Warner’s other pictures for Capra were You Can’t Take It with You (1938), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939, as the Senate majority leader) and Here Comes the Groom (1951).

In 1937, Capra gave Warner the opportunity to deliver probably his best screen performance. The picture was Lost Horizon, from James Hilton’s utopian romance about a group of refugees from war-torn “civilization” who find themselves in the remote Himalayan paradise of Shangri-La. Warner (here with Isabel Jewell, Edward Everett Horton, Ronald Colman and Thomas Mitchell) played Chang, their mysterious escort from the snowbound wreck of their plane to the Edenic Valley of the Blue Moon, and their host after they arrive. Endlessly cordial, welcoming and polite, he nevertheless is inscrutably vague about when and how they will ever be able to return to their homes. Warner got an Oscar nomination as best supporting actor, but he didn’t win; he lost out to Joseph Schildkraut as Alfred Dreyfus in Warner Bros.’ The Life of Emile Zola. That’s a worthy performance, but I’m not at all sure the Academy made the right call. H.B. Warner’s other pictures for Capra were You Can’t Take It with You (1938), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939, as the Senate majority leader) and Here Comes the Groom (1951).

H.B. Warner’s final screen appearance was a poignant one. He was approaching 80 and living at the Motion Picture Country Home in Woodland Hills in 1955 when the call came from his old friend Cecil B. DeMille. DeMille was planning a massive spectacle expanding the Biblical section of his 1923 hit The Ten Commandments, and he had a part for H.B. if he felt up to it. The role was identified in the script as “Amminadab”, an aging Israelite setting out on the Exodus from Egypt, even though he knows he’ll never see the Promised Land — indeed, probably won’t live out the day. The actor carrying him in this shot, Donald Curtis, remembered that Warner weighed no more than a child, and carrying him wasn’t merely in the script, it was a necessity: “It was clear H.B. couldn’t walk — could barely breathe.” He had come to the set in an ambulance and lay on a stretcher, breathing through an oxygen mask, until the cameras were ready to roll. In the script, he had a rather complex speech adapted from Psalm 22, but he couldn’t manage it, so DeMille told him to say whatever he wanted, and Curtis and Nina Foch would work with it. H.B. Warner’s last words in his 137th movie, after 53 years as an actor, were: “I am poured out like water, my strength dried up into the dust of death.”

H.B. Warner’s final screen appearance was a poignant one. He was approaching 80 and living at the Motion Picture Country Home in Woodland Hills in 1955 when the call came from his old friend Cecil B. DeMille. DeMille was planning a massive spectacle expanding the Biblical section of his 1923 hit The Ten Commandments, and he had a part for H.B. if he felt up to it. The role was identified in the script as “Amminadab”, an aging Israelite setting out on the Exodus from Egypt, even though he knows he’ll never see the Promised Land — indeed, probably won’t live out the day. The actor carrying him in this shot, Donald Curtis, remembered that Warner weighed no more than a child, and carrying him wasn’t merely in the script, it was a necessity: “It was clear H.B. couldn’t walk — could barely breathe.” He had come to the set in an ambulance and lay on a stretcher, breathing through an oxygen mask, until the cameras were ready to roll. In the script, he had a rather complex speech adapted from Psalm 22, but he couldn’t manage it, so DeMille told him to say whatever he wanted, and Curtis and Nina Foch would work with it. H.B. Warner’s last words in his 137th movie, after 53 years as an actor, were: “I am poured out like water, my strength dried up into the dust of death.”