The Bard of Burbank, Part 1

One night years ago I was showing a friend some scenes from the 1935 Warner Bros. movie of A Midsummer Night’s Dream — the gathering of the fairies, the magic woodland dances, things like that. “This movie,” I told her, “won an Academy Award for its cinematography. There are two amazing facts connected with that. One is that it’s the only Oscar ever awarded on a write-in vote.”

She raised her eyebrows. “You mean it wasn’t nominated?“

“That’s the other amazing fact.”

It is amazing. No disrespect to the three actual nominees that year (Barbary Coast, Les Miserables and The Crusades), but why wasn’t it? Hal Mohr’s cinematography was the one thing about Midsummer on which all commenters on the movie agreed at the time, and they still do now: this is one of the most beautiful black-and-white movies ever shot. Kevin Jack Hagopian of Penn State says Mohr sided with management in a union dispute and the cinematographers’ branch of the Academy refused to nominate him out of pure spite; that makes sense to me. Whatever the cause, a write-in campaign was organized; the Academy allowed write-ins for only two years (1934-35), and this is the only one that ever went the distance.

Mohr had replaced Ernest Haller on the picture when producer Henry Blanke and production chief Hal Wallis found Haller’s footage too murky and dark. Mohr decided it was a case of literally not seeing the forest for the trees, so he ripped out some of the trees designer Anton Grot had erected on the sound stage, had the remaining ones painted and aluminized to be more reflective, and made room for more lighting instruments.

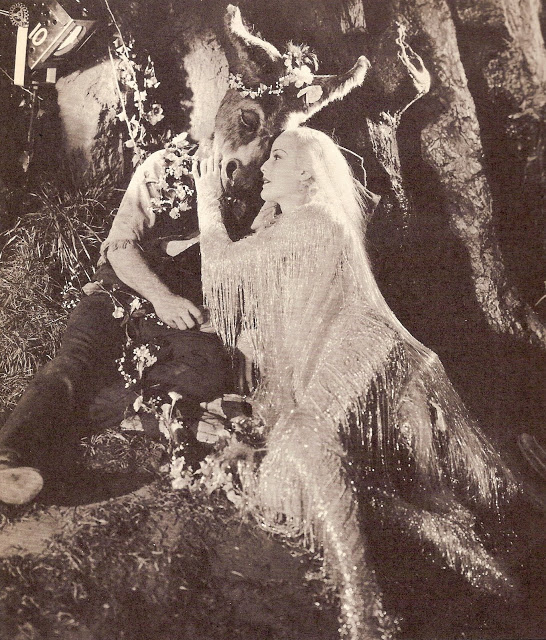

One of Mohr’s instruments is just visible in the corner of this picture; for some reason it wasn’t cropped or retouched out of sight in this version of what became one of the movie’s signature images: fairy queen Titania (Anita Louise) doting on the donkey-headed ass Nick Bottom (James Cagney). This picture was, in fact, my introduction to A Midsummer Night’s Dream in any form, when I came across it at the age of eight or nine, thumbing through a copy of Richard Griffith and Arthur Mayer’s 1956 coffee-table tome The Movies. This picture took up most of page 330; I remember it stopped me cold, and I stared at it a long time. What in the world, I thought, could possibly be the story behind a picture like this?

In time I became more familiar with A Midsummer Night’s Dream; I even directed a production of it during my college years, the only occasion on which I was able, without really trying, to commit an entire Shakespeare play to memory (and no, I can’t still remember it all). So now I know the story of how the glittering, tinselly queen of fairies and the blowhard weaver from working-class Athens come to be tenderly embracing under that tree — she madly in love, he crowned with an ass’s head, each in the grip of a different magic spell.

But my childhood question still stands: What is the story behind that picture — not Bottom and Titania, but A Midsummer Night’s Dream itself? What prompted Warner Bros., home studio of gangsters, fast-talking newsmen and working class stiffs, to take a chance on a highbrow director and a highbrow property, even one in the public domain? Prof. Hagopian says it was Jack Warner’s drive to crash high society, to prove to the upper crust that this son of Russian immigrants had kult-chah. Hmmm. Maybe, but I still wonder, was any amount of boulevard cred worth $1.5 million to this notorious penny-pincher?

Actually, according to historian Scott MacQueen in his commentary to the Midsummer DVD, it was Hal Wallis who prompted Warner to approach Max Reinhardt about committing A Midsummer Night’s Dream to film, and thereby must surely hang a tale. No doubt we could find it in the Warner Bros. archives, with that studio’s penchant for memos and paper trails (“Verbal communication leads to misunderstanding and mistakes. Put your ideas in writing.”), but nobody’s ever bothered to, evidently. There’s no section on Midsummer in Rudy Behlmer’s Inside Warner Bros., barely a sentence in Ted Sennett’s Warner Bros. Presents or in Hollywood Be Thy Name: The Warner Brothers Story by Cass Warner Sperling, Cork Millner and Jack Warner Jr. It’s been decades since I read Jack Warner’s My First Hundred Years in Hollywood, and if he said anything about it, the recollection of it is long gone by now.

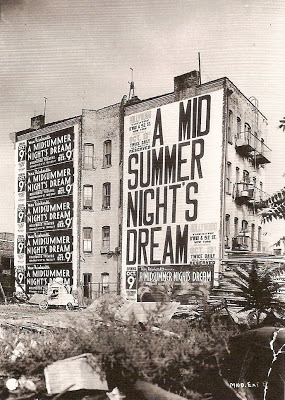

Some recounting of this undertaking is overdue, for A Midsummer Night’s Dream is another one of those “miracle pictures” I talked about in my post on Peter Ibbetson. (UPDATE 6/23/20: Since I wrote this in 2010, I’ve learned that my wish had already been granted, by the aforesaid Scott MacQueen, in a long making-of article for the Fall 2009 issue of The Moving Image: The Journal of the Association of Moving Image Archivists. It’s an excellent, eye-opening read, if you can find a copy of it. Try the Project Muse Web site.) Certainly it would have taken nothing less than a miracle for Warners to recoup their massive investment in it. Not that the studio’s publicity department didn’t give it the old college try. Here they’ve leased the whole side of a building in some blighted New York City neighborhood (Probably Brooklyn, Queens, or the Bronx; certainly not Manhattan) to proclaim the picture to anyone happening by the rubbish-strewn empty lot next door. There’s something wistfully gallant about the effort. Likewise the string of special announcement trailers to be found as supplements on the DVD, in which various cast members — Ian Hunter, Olivia de Havilland, Anita Louise, Dick Powell, etc. — step from behind a curtain to avow their pride in being part of Midsummer, all but pleading with the audience to turn out and prove their efforts from December 1934 to the following March had not been in vain.

Unfortunately, they were, as far as Warners’ bottom line for 1935 and ’36 was concerned. Midsummer did okay in the cities and not too bad overseas, but in the small towns it died a thousand deaths. Or three thousand; a record 2,971 theaters exercised their option to cancel their bookings. Jack Warner must have thanked his lucky stars (and the newest and luckiest of all, Errol Flynn) for the unexpected bonanza of Captain Blood.

Max Reinhardt was already an old hand at Shakespeare’s enchanted comedy by the time he strode onto the Warner Bros. lot. It was his favorite play, maybe because it was a 1905 production in Berlin that first made his name and set him on a course to virtually creating the theater-director-as-superstar, as we know the position today. According to his biographer J.L. Styan, Reinhardt had restaged the play over twenty-five times since then, including heralded productions in Oxford, New York and Berkeley.

It was his colossal production in the Hollywood Bowl that piqued Hal Wallis’s interest. For that, Reinhardt removed the famous band shell (what most people think of as the “bowl”; actually, the term refers to the topography of the site) and replaced it with a 25,000-square-foot stage; he had tons of soil trucked in to construct an artificial forest on the hillside behind, including a pond and suspension bridge, to be lined with torch-bearers for the big wedding procession between Acts IV and V.

Oddly enough, for years Reinhardt had been moving in a more minimalist direction for Midsummer; by 1925 he was staging it on a virtually bare stage with only green curtains to suggest the woods outside Athens. But for the Hollywood Bowl, and later for Warner Bros., he returned to the elaborate pageantry that had characterized the play through much of the 19th century.

In the 1940s and ’50s, Laurence Olivier would revolutionize the practice of filming Shakespeare, setting the bar for all who followed. But in 1935 the only bar was imported from the stage. There had been a film inspired by Midsummer in 1909, but that could be no use to anyone now. Reinhardt himself had directed movies in the silent era, but his metier was the stage, and it might have been the undoing of A Midsummer Night’s Dream had his direction carried the day. James Cagney and other members of the cast later recounted how he stalked up and down giving his own rendition of their characters, gesticulating and declaiming wildly (in German) as if he imagined they were still on that huge stage at the Hollywood Bowl projecting to an audience of 15,000 sitting hundreds of yards away. “Somebody ought to tell him,” they whispered.

Not to worry. Reinhardt’s grip of English was shaky, and consequently so was his control of the actors, which fell to William (ne Wilhelm) Dieterle. Dieterle had been a protege of Reinhardt’s in Berlin before becoming a movie director and actor and, in 1931, going over to work in Hollywood, where he flourished. Under contract to Warners in 1934, he was assigned to Midsummer ostensibly as co-director, but actually as a sort of majordomo; he and producer Blanke served as the maestro’s interpreters, and actors and technicians alike remembered the three of them barging into the soundstages where the sets were under construction, growling and barking among themselves in German.

Not to worry. Reinhardt’s grip of English was shaky, and consequently so was his control of the actors, which fell to William (ne Wilhelm) Dieterle. Dieterle had been a protege of Reinhardt’s in Berlin before becoming a movie director and actor and, in 1931, going over to work in Hollywood, where he flourished. Under contract to Warners in 1934, he was assigned to Midsummer ostensibly as co-director, but actually as a sort of majordomo; he and producer Blanke served as the maestro’s interpreters, and actors and technicians alike remembered the three of them barging into the soundstages where the sets were under construction, growling and barking among themselves in German.As things turned out, Dieterle was more the director than Reinhardt once the cameras began rolling; Mickey Rooney, who played Puck, said Dieterle was the only director he ever worked with on the movie (he had also worked for Reinhardt in the Hollywood Bowl). Dieterle bristled at having to play second fiddle to Reinhardt in studio publicity, and he said so to Jack Warner. Warner understood, but explained that — to put it more bluntly than he did — Reinhardt had a name and Dieterle didn’t; the studio’s huge investment had to be protected, and the only way to do it, he figured, was to play up “A Max Reinhardt Production” to the max (pun intended).

In the final analysis, the dual director credit was probably just; let’s give Reinhardt credit for conception and Dieterle for execution, each taking the lead where the other was less at home. In Part 2, I’ll talk a little more about both facets — conception and execution — of the final product.

To be concluded…