The Rubaiyat of Eugene O’Neill

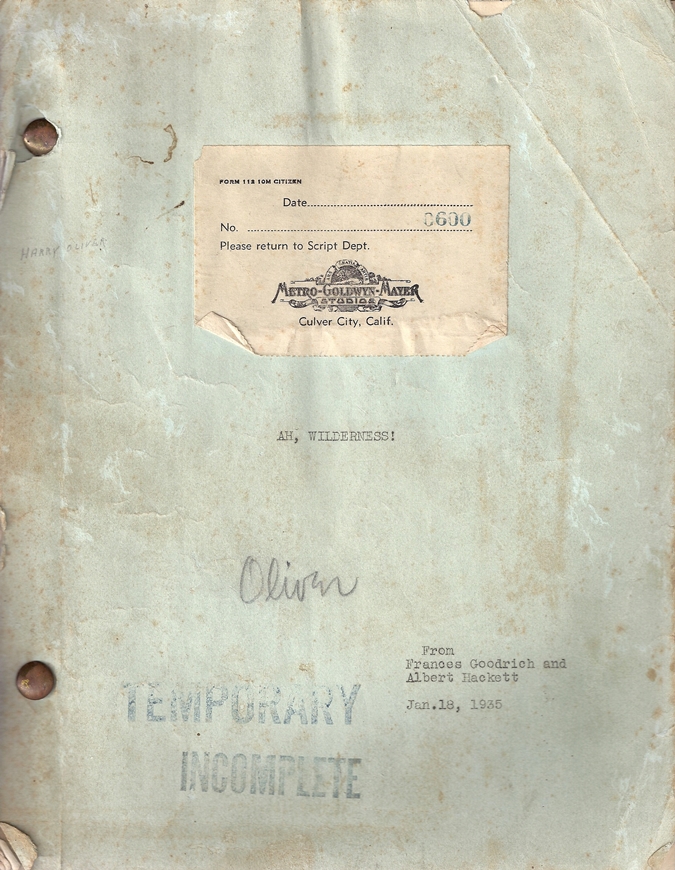

An interesting artifact has come into my hands on loan from an old friend. It’s an early draft of the screenplay for MGM’s 1935 movie of Eugene O’Neill’s Ah, Wilderness! by the husband-and-wife team of Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett.

An interesting artifact has come into my hands on loan from an old friend. It’s an early draft of the screenplay for MGM’s 1935 movie of Eugene O’Neill’s Ah, Wilderness! by the husband-and-wife team of Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett.

It’s a very early draft, in fact — labeled both TEMPORARY and INCOMPLETE and dated January 18, 1935. The picture’s premiere (in Worcester, Mass.) wasn’t until December 6, and it didn’t open in New York until Christmas Day. I don’t know when it opened in Los Angeles, but Variety’s review (and they were always very prompt) finally appeared January 1, 1936 — nearly a full year after this draft started making the rounds at the Culver City studio.

Exactly what rounds did it make? Well, obviously it never made it back to the Script Dept., despite the request on the cover. The names “Oliver” and (smaller, more faintly) “Harry Oliver” are pencilled on the cover. Harry Oliver worked as an art director in Hollywood in the ’20s and ’30s, including (but not exclusively) at MGM; his IMDb page lists credits with Fox before the 20th Century merger (two of which, 7th Heaven and Street Angel, garnered him Oscar nominations), with Harold Lloyd, and with independent producer Sol Lesser. He’s not among the names credited on Ah, Wilderness!, but that doesn’t mean he didn’t work on it; MGM was all one big family in those days, and crafts technicians didn’t get credit for every lick of work they did. My guess is that when Ah, Wilderness! was in pre-production, the Art Department got a number of scripts for budget estimating purposes, and Harry Oliver got one of them to look over and offer input. How it got out of his hands (Oliver died in 1973) and wound up in my friend’s wife’s friend’s uncle’s box of mementos is anybody’s guess.

The “600” stamped on the label isn’t the number of this individual script, it’s the picture’s production number — meaning this was the six-hundredth feature initiated since the founding of MGM in 1924. The “Incomplete” stamp is literal: the last page of the script, p. 93, ends at a point where the finished film still has 32 of its 97 minutes left to run. The “Temporary” stamp means “Tentative”; there are many minor and two major differences between what the Hacketts had written by January 18 and what eventually turned up on the screen.

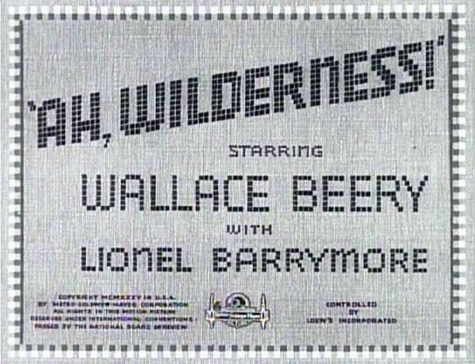

The first major difference is in the treatment of Wallace Beery’s role. Beery (left) gets top billing in the picture, playing Sid Davis, the brother of Spring Byington’s Essie Miller and the brother-in-law of Essie’s husband Nat (second-billed Lionel Barrymore, right). O’Neill’s play all takes place on one day — July 4, 1906 — but the Hacketts had expanded the time frame to open a week or two earlier (“late June”), before Sid enters the action (he comes back to the Miller household after being fired for drunkenness from his newspaper job in a neighboring town). So in this January 18 draft, Sid doesn’t show up until page 40 (of 93), on the morning of the Fourth. This would hardly do for a star of Beery’s standing at the time (I wouldn’t put it past him to have griped about it himself, loud and long), so a scene was added showing him going off with high hopes — for both his new job and his newfound sobriety — at the end of June, before slinking back to the Millers in time for the holiday. (“Ma! Pa! Uncle Sid’s come to spend the Fourth!” To which Sid mutters under his breath: “The Fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth, ad infinitum.”)

The first major difference is in the treatment of Wallace Beery’s role. Beery (left) gets top billing in the picture, playing Sid Davis, the brother of Spring Byington’s Essie Miller and the brother-in-law of Essie’s husband Nat (second-billed Lionel Barrymore, right). O’Neill’s play all takes place on one day — July 4, 1906 — but the Hacketts had expanded the time frame to open a week or two earlier (“late June”), before Sid enters the action (he comes back to the Miller household after being fired for drunkenness from his newspaper job in a neighboring town). So in this January 18 draft, Sid doesn’t show up until page 40 (of 93), on the morning of the Fourth. This would hardly do for a star of Beery’s standing at the time (I wouldn’t put it past him to have griped about it himself, loud and long), so a scene was added showing him going off with high hopes — for both his new job and his newfound sobriety — at the end of June, before slinking back to the Millers in time for the holiday. (“Ma! Pa! Uncle Sid’s come to spend the Fourth!” To which Sid mutters under his breath: “The Fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth, ad infinitum.”)

As for the second major difference, it’s another scene that doesn’t appear in O’Neill’s play — a major one, just over 15 minutes long. I don’t know when it was inserted into the script, but God bless the Hacketts for writing it, and Clarence Brown for directing it so beautifully, because it’s one of the best and funniest scenes in the whole movie. Most of it takes place during the graduation ceremony at the high school in this small Connecticut city, where Nat and Essie Miller’s middle son Richard (Eric Linden) will be the valedictorian. Before Richard’s speech, however, we’re treated to a generous sampling of the commencement program: the school glee club singing “The Blue Danube”, an earnest young student reciting Mark Antony’s funeral oration from Julius Caesar; a more nervous youngster offering Poe’s “The Bells” (“…of the bells bells bells bells bells bells bells…”) and studiously counting every “bells” off on his fingers; a girl student’s how-I-spent-my-summer-vacation travelogue about her family’s visit to the Swiss Alps; and my favorite, this young lady (I wish I knew her name) struggling doggedly through a clarinet solo, darting irritated glances toward her piano accompanist at every real and imagined mistake.

As for the second major difference, it’s another scene that doesn’t appear in O’Neill’s play — a major one, just over 15 minutes long. I don’t know when it was inserted into the script, but God bless the Hacketts for writing it, and Clarence Brown for directing it so beautifully, because it’s one of the best and funniest scenes in the whole movie. Most of it takes place during the graduation ceremony at the high school in this small Connecticut city, where Nat and Essie Miller’s middle son Richard (Eric Linden) will be the valedictorian. Before Richard’s speech, however, we’re treated to a generous sampling of the commencement program: the school glee club singing “The Blue Danube”, an earnest young student reciting Mark Antony’s funeral oration from Julius Caesar; a more nervous youngster offering Poe’s “The Bells” (“…of the bells bells bells bells bells bells bells…”) and studiously counting every “bells” off on his fingers; a girl student’s how-I-spent-my-summer-vacation travelogue about her family’s visit to the Swiss Alps; and my favorite, this young lady (I wish I knew her name) struggling doggedly through a clarinet solo, darting irritated glances toward her piano accompanist at every real and imagined mistake. In their adaptation, the Hacketts emphasized the one slim thread of plot in O’Neill’s nostalgic reverie of a youth he never had: the emotional growing pains of the Millers’ middle son Richard, from his jejune flirtation with radical politics to his blossoming romance with neighbor girl Muriel McComber (Cecilia Parker) and the mean-spirited oppostion of her father. In so doing, the Hacketts handed 25-year-old Eric Linden the opportunity to give the performance of his career — and he delivered in style. Never mind that he gets no better than fourth billing; Ah, Wilderness! is Eric Linden’s picture from beginning to end. And never mind that he was a good decade too old for the role; his boyishness made him look not a day over 16, and his performance did the rest. Linden had a busy career in the 1930s — mostly in B-pictures for RKO, Warners and MGM — without ever really becoming a star; this was his only chance to carry an A-picture on his own. After this it was back to Bs at Metro and on loan to various studios and independent producers. But before he finally closed out his career in 1943 with Criminals Within (for lowly Producers Releasing Corporation, the skid row flophouse of Hollywood studios), he would give one more performance that I’m sure everyone who ever saw it will remember to their dying day:

In their adaptation, the Hacketts emphasized the one slim thread of plot in O’Neill’s nostalgic reverie of a youth he never had: the emotional growing pains of the Millers’ middle son Richard, from his jejune flirtation with radical politics to his blossoming romance with neighbor girl Muriel McComber (Cecilia Parker) and the mean-spirited oppostion of her father. In so doing, the Hacketts handed 25-year-old Eric Linden the opportunity to give the performance of his career — and he delivered in style. Never mind that he gets no better than fourth billing; Ah, Wilderness! is Eric Linden’s picture from beginning to end. And never mind that he was a good decade too old for the role; his boyishness made him look not a day over 16, and his performance did the rest. Linden had a busy career in the 1930s — mostly in B-pictures for RKO, Warners and MGM — without ever really becoming a star; this was his only chance to carry an A-picture on his own. After this it was back to Bs at Metro and on loan to various studios and independent producers. But before he finally closed out his career in 1943 with Criminals Within (for lowly Producers Releasing Corporation, the skid row flophouse of Hollywood studios), he would give one more performance that I’m sure everyone who ever saw it will remember to their dying day: He was the Confederate soldier in Gone With the Wind who has just learned from Harry Davenport’s Dr. Meade that his leg will have to be amputated. He is on screen for less than three seconds, but his desperate cries (“Don’t cut! Don’t! — cut! Ple-e-e-e-ease!!”) have curdled the blood of millions of moviegoers for over 70 years. Oh yes, I’ll just bet you remember Eric Linden, all right.

He was the Confederate soldier in Gone With the Wind who has just learned from Harry Davenport’s Dr. Meade that his leg will have to be amputated. He is on screen for less than three seconds, but his desperate cries (“Don’t cut! Don’t! — cut! Ple-e-e-e-ease!!”) have curdled the blood of millions of moviegoers for over 70 years. Oh yes, I’ll just bet you remember Eric Linden, all right. The Hacketts deftly tinkered with the letter of O’Neill’s play, but Ah, Wilderness! the movie remained stoutly faithful to its spirit, and for that, a good share of the credit should go to director Clarence Brown. Brown’s career and work deserve more attention than they’ve gotten, and maybe someday I’ll have more to say about him. For now, I’ll simply observe that in his 53 pictures between 1920 and 1952 he directed a striking number of performers to their best-ever performances: Eric Linden here, Elizabeth Taylor in National Velvet, Claude Jarman Jr. in The Yearling, Juano Hernandez in Intruder in the Dust, George Brent in The Rains Came, Marie Dressler in Emma, and so on. An equally striking number gave their near-best for him: Garbo and Basil Rathbone in Anna Karenina, Mickey Rooney and Frank Morgan in The Human Comedy, Charles Boyer in Conquest, Paul Douglas in Angels in the Outfield — well, you get the idea. I could do a whole post just on Brown’s contribution to Ah, Wilderness!, but my topic here is what the picture’s success led to for MGM and Hollywood — consequences beyond what anyone could have expected. Clarence Brown had a lot to do with that success; let’s just leave it at that.

The Hacketts deftly tinkered with the letter of O’Neill’s play, but Ah, Wilderness! the movie remained stoutly faithful to its spirit, and for that, a good share of the credit should go to director Clarence Brown. Brown’s career and work deserve more attention than they’ve gotten, and maybe someday I’ll have more to say about him. For now, I’ll simply observe that in his 53 pictures between 1920 and 1952 he directed a striking number of performers to their best-ever performances: Eric Linden here, Elizabeth Taylor in National Velvet, Claude Jarman Jr. in The Yearling, Juano Hernandez in Intruder in the Dust, George Brent in The Rains Came, Marie Dressler in Emma, and so on. An equally striking number gave their near-best for him: Garbo and Basil Rathbone in Anna Karenina, Mickey Rooney and Frank Morgan in The Human Comedy, Charles Boyer in Conquest, Paul Douglas in Angels in the Outfield — well, you get the idea. I could do a whole post just on Brown’s contribution to Ah, Wilderness!, but my topic here is what the picture’s success led to for MGM and Hollywood — consequences beyond what anyone could have expected. Clarence Brown had a lot to do with that success; let’s just leave it at that.

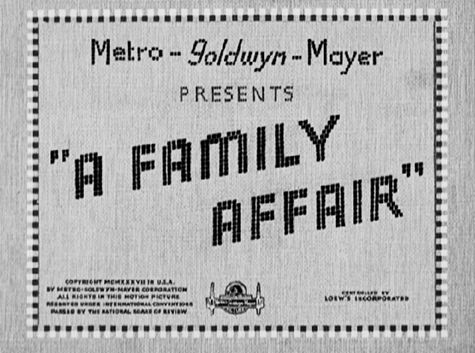

When the picture went into production in the fall of 1936, Aurania Rouverol’s Skidding had a new title, A Family Affair, and George B. Seitz was directing from a script by Kay Van Riper. It reunited a hefty chunk of the cast from Ah, Wilderness!: Lionel Barrymore, Spring Byington, Mickey Rooney, Charles Grapewin. Also back were Eric Linden and Cecilia Parker, romantically paired once again — only this time she was the one in the family and he was the neighboring sweetheart. The picture was shot on the same backlot “New England Street” that had been built for Ah, Wilderness!, and the new family “lived” in the same house. If you have any lingering doubt that this new picture was designed to evoke pleasant memories of the earlier one, here’s the title frame from Ah, Wilderness!…

When the picture went into production in the fall of 1936, Aurania Rouverol’s Skidding had a new title, A Family Affair, and George B. Seitz was directing from a script by Kay Van Riper. It reunited a hefty chunk of the cast from Ah, Wilderness!: Lionel Barrymore, Spring Byington, Mickey Rooney, Charles Grapewin. Also back were Eric Linden and Cecilia Parker, romantically paired once again — only this time she was the one in the family and he was the neighboring sweetheart. The picture was shot on the same backlot “New England Street” that had been built for Ah, Wilderness!, and the new family “lived” in the same house. If you have any lingering doubt that this new picture was designed to evoke pleasant memories of the earlier one, here’s the title frame from Ah, Wilderness!…

…and here’s the same frame from A Family Affair. The new picture took place in the “present day” (i.e., 1936) instead of a rose-colored turn of the century, but otherwise it followed the benevolent formula laid down by Eugene O’Neill in his change-of-pace comedy: the friendly, cozy big-small-town where everybody knows everybody else, the close-knit family bound by ties of affection and respect, the periodic heart-to-heart talks between father and son. The family of newspaper publisher Nat Miller in Ah, Wilderness! were the clear progenitors of Judge James K. Hardy and his clan — at least, by the time MGM had brought the Hardys to the screen. (In fact, ironically, Aurania Rouverol’s play had beaten O’Neill’s to Broadway by nearly five-and-a-half years; Skidding had a longer run, too.)

…and here’s the same frame from A Family Affair. The new picture took place in the “present day” (i.e., 1936) instead of a rose-colored turn of the century, but otherwise it followed the benevolent formula laid down by Eugene O’Neill in his change-of-pace comedy: the friendly, cozy big-small-town where everybody knows everybody else, the close-knit family bound by ties of affection and respect, the periodic heart-to-heart talks between father and son. The family of newspaper publisher Nat Miller in Ah, Wilderness! were the clear progenitors of Judge James K. Hardy and his clan — at least, by the time MGM had brought the Hardys to the screen. (In fact, ironically, Aurania Rouverol’s play had beaten O’Neill’s to Broadway by nearly five-and-a-half years; Skidding had a longer run, too.)

A Family Affair was an unexpected hit, particularly for a B picture, and exhibitors besieged MGM with requests for more, especially more of Mickey Rooney, who played Judge Hardy’s teenage son Andy — the clear equivalent of Eric Linden’s Richard Miller in Ah, Wilderness! By the time the studio could get a sequel underway, Lionel Barrymore and Spring Byington had moved on to other projects and were unavailable. They were replaced by Lewis Stone and Fay Holden as Judge and Mrs. Hardy, and You’re Only Young Once became, officially, the first installment of the Andy Hardy series — and the only one not to have the name “Hardy” in the title.

The Andy Hardy pictures, 15 of them between 1937 and 1946, became the most successful series in movie history before the James Bond movies — and in fact, if we think of it in terms of percent of profit for cost of production, they may still hold the record. There’s no telling how many of MGM’s expensive, prestigious failures had their fingers pulled out of the financial fire by the Hardy family. The series served as a training ground for future MGM stars — Lana Turner, Ava Gardner, Esther Williams, Kathryn Grayson, Donna Reed, and of course Judy Garland — who one way or another would cross Andy Hardy’s path. It made Mickey Rooney the number-one box office star in America for three years running. It was pointed to by Louis B. Mayer as his proudest achievement. It won MGM a special Academy Award (certificate) in 1942 for “representing the American way of life”. In 1941 Los Angeles Mayor Fletcher Bowron proclaimed the Hardys “the first family of Hollywood”, commemorated by a plaque in the forecourt of Grauman’s Chinese Theatre.

By the way, don’t go looking for that plaque; it isn’t there any more. The Andy Hardy pictures have long gone (unjustly) out of vogue. A few were issued on VHS years ago, but only one (so far) has made it to DVD, and that from the bargain-basement Warner Archive. (It’s Love Finds Andy Hardy, and it’s available, no doubt, only because Judy Garland co-stars with Mickey.) (UPDATE 12/23/11: The Warner Archive has begun to rectify this; they’ve just issued The Andy Hardy Collection, Vol. 1 with six of the early titles.) (UPDATE 7/12/13: The rectification is now complete: Warner Archive has issued The Andy Hardy Film Collection, Vol. 2 with the remaining ten features. Titles are also available individually.)

Mickey Rooney had an interesting take on the series: “Creating this New England utopia was all part of L.B. Mayer’s master plan to reinvent America. In most of his movies that came under his control, Mr. Mayer knew that he was ‘confecting, not reflecting’ America…The Andy Hardy movies didn’t tell it ‘like it is.’ They told it the way we’d like it to be, describing an ideal that needs constant reinvention.”

In 1946, the year of the last regular Andy Hardy picture (Love Laughs at Andy Hardy), there was a sort of closing of the circle on Ah, Wilderness! Producer Arthur Freed, still flush from his rousing success with Meet Me in St. Louis (which itself was a very close cousin to Ah, Wilderness!) conceived the idea of turning O’Neill’s play into a musical. So the Hardys moved out of their comfy white house and the Millers moved back in (and painted it yellow for Technicolor), and the result was Summer Holiday. This time Andy Hardy himself, Mickey Rooney (who had played Tommy, the youngest Miller boy, in Ah, Wilderness!), was promoted into the role of Richard Miller, and Richard and his Muriel (Gloria DeHaven) got the top billing (thanks to the Hacketts’ tweakings of O’Neill, here preserved and enhanced) that Eric Linden and Cecilia Parker had deserved but been denied in 1935.

In 1946, the year of the last regular Andy Hardy picture (Love Laughs at Andy Hardy), there was a sort of closing of the circle on Ah, Wilderness! Producer Arthur Freed, still flush from his rousing success with Meet Me in St. Louis (which itself was a very close cousin to Ah, Wilderness!) conceived the idea of turning O’Neill’s play into a musical. So the Hardys moved out of their comfy white house and the Millers moved back in (and painted it yellow for Technicolor), and the result was Summer Holiday. This time Andy Hardy himself, Mickey Rooney (who had played Tommy, the youngest Miller boy, in Ah, Wilderness!), was promoted into the role of Richard Miller, and Richard and his Muriel (Gloria DeHaven) got the top billing (thanks to the Hacketts’ tweakings of O’Neill, here preserved and enhanced) that Eric Linden and Cecilia Parker had deserved but been denied in 1935. Even by 1948, the “reinventions” — of America and of Ah, Wilderness! — that Mickey Rooney talked about had begun to outstrip Andy Hardy, but Andy cast a long shadow for decades after the series itself ebbed. Sometimes the influence was direct and deliberate, as with the Archie comics that started in 1941 in blatant imitation of Andy Hardy and are still around today. Sometimes it was indirect but distinct, as in TV sitcoms from Father Knows Best and Leave It to Beaver, through The Partridge Family and The Brady Bunch, to Eight Is Enough and Modern Family. In them all, we can still discern the basic template with which L.B. Mayer “confected” small-town American life, in MGM’s conscious imitation of the way Eugene O’Neill had “confected” an imaginary youth for himself in New London, Conn. The shadow of Andy Hardy is really the shadow of Ah, Wilderness! (And let’s not forget Meet Me in St. Louis and the Technicolor musicals inspired by it, like Centennial Summer, State Fair, On Moonlight Bay, By the Light of the Silvery Moon, and yes, Summer Holiday, all with a clear kinship to O’Neill’s comedy.)

Even by 1948, the “reinventions” — of America and of Ah, Wilderness! — that Mickey Rooney talked about had begun to outstrip Andy Hardy, but Andy cast a long shadow for decades after the series itself ebbed. Sometimes the influence was direct and deliberate, as with the Archie comics that started in 1941 in blatant imitation of Andy Hardy and are still around today. Sometimes it was indirect but distinct, as in TV sitcoms from Father Knows Best and Leave It to Beaver, through The Partridge Family and The Brady Bunch, to Eight Is Enough and Modern Family. In them all, we can still discern the basic template with which L.B. Mayer “confected” small-town American life, in MGM’s conscious imitation of the way Eugene O’Neill had “confected” an imaginary youth for himself in New London, Conn. The shadow of Andy Hardy is really the shadow of Ah, Wilderness! (And let’s not forget Meet Me in St. Louis and the Technicolor musicals inspired by it, like Centennial Summer, State Fair, On Moonlight Bay, By the Light of the Silvery Moon, and yes, Summer Holiday, all with a clear kinship to O’Neill’s comedy.)

With all due respect to the titanic power of plays like Long Day’s Journey into Night, The Iceman Cometh and Mourning Becomes Electra, it just may be that Ah, Wilderness! was in fact the most influential play Eugene O’Neill ever wrote.

Jim – Happy to report I've found a DVD copy of "Ah, Wilderness!" via a local library system and should have it soon.

I, too, believe Hepburn gives the performance of her life in "Long Day's Journey…" A very different role for her and she leaves no question of her capability as an actress (she stuck to type for most of her films and I've sometimes thought less of her as an actress because of it). Her rendition of Mary Tyrone's soliloquy is just breathtaking. Lumet's entire cast is superb and, for me, his film captures O'Neill's dark, anguished mood beautifully.