The Bard of Burbank, Part 1

One night years ago I was showing a friend some scenes from the 1935 Warner Bros. movie of A Midsummer Night’s Dream — the gathering of the fairies, the magic woodland dances, things like that. “This movie,” I told her, “won an Academy Award for its cinematography. There are two amazing facts connected with that. One is that it’s the only Oscar ever awarded on a write-in vote.”

She raised her eyebrows. “You mean it wasn’t nominated?“

“That’s the other amazing fact.”

It is amazing. No disrespect to the three actual nominees that year (Barbary Coast, Les Miserables and The Crusades), but why wasn’t it? Hal Mohr’s cinematography was the one thing about Midsummer on which all commenters on the movie agreed at the time, and they still do now: this is one of the most beautiful black-and-white movies ever shot. Kevin Jack Hagopian of Penn State says Mohr sided with management in a union dispute and the cinematographers’ branch of the Academy refused to nominate him out of pure spite; that makes sense to me. Whatever the cause, a write-in campaign was organized; the Academy allowed write-ins for only two years (1934-35), and this is the only one that ever went the distance.

Mohr had replaced Ernest Haller on the picture when producer Henry Blanke and production chief Hal Wallis found Haller’s footage too murky and dark. Mohr decided it was a case of literally not seeing the forest for the trees, so he ripped out some of the trees designer Anton Grot had erected on the sound stage, had the remaining ones painted and aluminized to be more reflective, and made room for more lighting instruments.

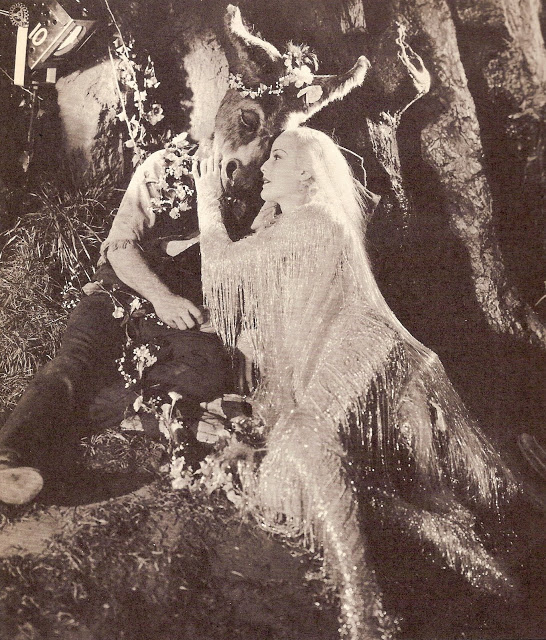

One of Mohr’s instruments is just visible in the corner of this picture; for some reason it wasn’t cropped or retouched out of sight in this version of what became one of the movie’s signature images: fairy queen Titania (Anita Louise) doting on the donkey-headed ass Nick Bottom (James Cagney). This picture was, in fact, my introduction to A Midsummer Night’s Dream in any form, when I came across it at the age of eight or nine, thumbing through a copy of Richard Griffith and Arthur Mayer’s 1956 coffee-table tome The Movies. This picture took up most of page 330; I remember it stopped me cold, and I stared at it a long time. What in the world, I thought, could possibly be the story behind a picture like this?

In time I became more familiar with A Midsummer Night’s Dream; I even directed a production of it during my college years, the only occasion on which I was able, without really trying, to commit an entire Shakespeare play to memory (and no, I can’t still remember it all). So now I know the story of how the glittering, tinselly queen of fairies and the blowhard weaver from working-class Athens come to be tenderly embracing under that tree — she madly in love, he crowned with an ass’s head, each in the grip of a different magic spell.

But my childhood question still stands: What is the story behind that picture — not Bottom and Titania, but A Midsummer Night’s Dream itself? What prompted Warner Bros., home studio of gangsters, fast-talking newsmen and working class stiffs, to take a chance on a highbrow director and a highbrow property, even one in the public domain? Prof. Hagopian says it was Jack Warner’s drive to crash high society, to prove to the upper crust that this son of Russian immigrants had kult-chah. Hmmm. Maybe, but I still wonder, was any amount of boulevard cred worth $1.5 million to this notorious penny-pincher?

Actually, according to historian Scott MacQueen in his commentary to the Midsummer DVD, it was Hal Wallis who prompted Warner to approach Max Reinhardt about committing A Midsummer Night’s Dream to film, and thereby must surely hang a tale. No doubt we could find it in the Warner Bros. archives, with that studio’s penchant for memos and paper trails (“Verbal communication leads to misunderstanding and mistakes. Put your ideas in writing.”), but nobody’s ever bothered to, evidently. There’s no section on Midsummer in Rudy Behlmer’s Inside Warner Bros., barely a sentence in Ted Sennett’s Warner Bros. Presents or in Hollywood Be Thy Name: The Warner Brothers Story by Cass Warner Sperling, Cork Millner and Jack Warner Jr. It’s been decades since I read Jack Warner’s My First Hundred Years in Hollywood, and if he said anything about it, the recollection of it is long gone by now.

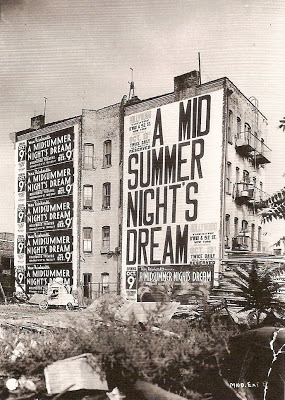

Some recounting of this undertaking is overdue, for A Midsummer Night’s Dream is another one of those “miracle pictures” I talked about in my post on Peter Ibbetson. (UPDATE 6/23/20: Since I wrote this in 2010, I’ve learned that my wish had already been granted, by the aforesaid Scott MacQueen, in a long making-of article for the Fall 2009 issue of The Moving Image: The Journal of the Association of Moving Image Archivists. It’s an excellent, eye-opening read, if you can find a copy of it. Try the Project Muse Web site.) Certainly it would have taken nothing less than a miracle for Warners to recoup their massive investment in it. Not that the studio’s publicity department didn’t give it the old college try. Here they’ve leased the whole side of a building in some blighted New York City neighborhood (Probably Brooklyn, Queens, or the Bronx; certainly not Manhattan) to proclaim the picture to anyone happening by the rubbish-strewn empty lot next door. There’s something wistfully gallant about the effort. Likewise the string of special announcement trailers to be found as supplements on the DVD, in which various cast members — Ian Hunter, Olivia de Havilland, Anita Louise, Dick Powell, etc. — step from behind a curtain to avow their pride in being part of Midsummer, all but pleading with the audience to turn out and prove their efforts from December 1934 to the following March had not been in vain.

Unfortunately, they were, as far as Warners’ bottom line for 1935 and ’36 was concerned. Midsummer did okay in the cities and not too bad overseas, but in the small towns it died a thousand deaths. Or three thousand; a record 2,971 theaters exercised their option to cancel their bookings. Jack Warner must have thanked his lucky stars (and the newest and luckiest of all, Errol Flynn) for the unexpected bonanza of Captain Blood.

Max Reinhardt was already an old hand at Shakespeare’s enchanted comedy by the time he strode onto the Warner Bros. lot. It was his favorite play, maybe because it was a 1905 production in Berlin that first made his name and set him on a course to virtually creating the theater-director-as-superstar, as we know the position today. According to his biographer J.L. Styan, Reinhardt had restaged the play over twenty-five times since then, including heralded productions in Oxford, New York and Berkeley.

It was his colossal production in the Hollywood Bowl that piqued Hal Wallis’s interest. For that, Reinhardt removed the famous band shell (what most people think of as the “bowl”; actually, the term refers to the topography of the site) and replaced it with a 25,000-square-foot stage; he had tons of soil trucked in to construct an artificial forest on the hillside behind, including a pond and suspension bridge, to be lined with torch-bearers for the big wedding procession between Acts IV and V.

Oddly enough, for years Reinhardt had been moving in a more minimalist direction for Midsummer; by 1925 he was staging it on a virtually bare stage with only green curtains to suggest the woods outside Athens. But for the Hollywood Bowl, and later for Warner Bros., he returned to the elaborate pageantry that had characterized the play through much of the 19th century.

In the 1940s and ’50s, Laurence Olivier would revolutionize the practice of filming Shakespeare, setting the bar for all who followed. But in 1935 the only bar was imported from the stage. There had been a film inspired by Midsummer in 1909, but that could be no use to anyone now. Reinhardt himself had directed movies in the silent era, but his metier was the stage, and it might have been the undoing of A Midsummer Night’s Dream had his direction carried the day. James Cagney and other members of the cast later recounted how he stalked up and down giving his own rendition of their characters, gesticulating and declaiming wildly (in German) as if he imagined they were still on that huge stage at the Hollywood Bowl projecting to an audience of 15,000 sitting hundreds of yards away. “Somebody ought to tell him,” they whispered.

Not to worry. Reinhardt’s grip of English was shaky, and consequently so was his control of the actors, which fell to William (ne Wilhelm) Dieterle. Dieterle had been a protege of Reinhardt’s in Berlin before becoming a movie director and actor and, in 1931, going over to work in Hollywood, where he flourished. Under contract to Warners in 1934, he was assigned to Midsummer ostensibly as co-director, but actually as a sort of majordomo; he and producer Blanke served as the maestro’s interpreters, and actors and technicians alike remembered the three of them barging into the soundstages where the sets were under construction, growling and barking among themselves in German.

Not to worry. Reinhardt’s grip of English was shaky, and consequently so was his control of the actors, which fell to William (ne Wilhelm) Dieterle. Dieterle had been a protege of Reinhardt’s in Berlin before becoming a movie director and actor and, in 1931, going over to work in Hollywood, where he flourished. Under contract to Warners in 1934, he was assigned to Midsummer ostensibly as co-director, but actually as a sort of majordomo; he and producer Blanke served as the maestro’s interpreters, and actors and technicians alike remembered the three of them barging into the soundstages where the sets were under construction, growling and barking among themselves in German.As things turned out, Dieterle was more the director than Reinhardt once the cameras began rolling; Mickey Rooney, who played Puck, said Dieterle was the only director he ever worked with on the movie (he had also worked for Reinhardt in the Hollywood Bowl). Dieterle bristled at having to play second fiddle to Reinhardt in studio publicity, and he said so to Jack Warner. Warner understood, but explained that — to put it more bluntly than he did — Reinhardt had a name and Dieterle didn’t; the studio’s huge investment had to be protected, and the only way to do it, he figured, was to play up “A Max Reinhardt Production” to the max (pun intended).

In the final analysis, the dual director credit was probably just; let’s give Reinhardt credit for conception and Dieterle for execution, each taking the lead where the other was less at home. In Part 2, I’ll talk a little more about both facets — conception and execution — of the final product.

To be concluded…

The Bard of Burbank, Part 2

“Was Warner Bros.’ film the glorious climax of Shakespearean art,” asks Scott MacQueen in his commentary on the DVD of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, “or just another sign that the Day of the Locust was at hand?” It’s a good question, and I’ll address it in due course.

“Was Warner Bros.’ film the glorious climax of Shakespearean art,” asks Scott MacQueen in his commentary on the DVD of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, “or just another sign that the Day of the Locust was at hand?” It’s a good question, and I’ll address it in due course.

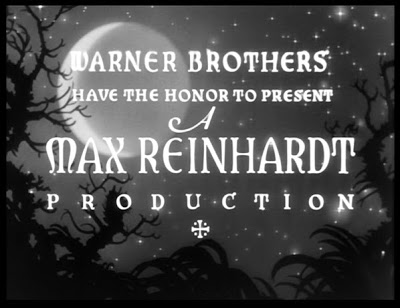

First, though, let’s take a look at the opening title that appears on the Midsummer screen. I wonder: Is this the only time the word “Brothers” was ever spelled out in a Warner Bros. picture? (They didn’t do it for Anthony Adverse, the studio’s big prestige spectacular of the following year.) Somehow it seems to lend an intimate touch, as if the title card were speaking for Harry, Albert and Jack Warner personally, not merely the corporate entity whose official name was “Warner Bros. Pictures.” At the same time, there’s an almost endearing air of self-conscious dignity about it. Deference too — notice that Max Reinhardt gets bigger billing than the brothers themselves.

Notice something else, the background. It’s an image that appears again early in the movie, as the scene shifts from Athens to the forest fairyland. There’s the moon exactly as it’s described by Hippolyta, Queen of the Amazons, “like to a silver bow/New-bent in heaven.” It’s the kind of touch that ruffled the feathers of some of the movie’s snootier critics (especially in Great Britain), a sign that (in their eyes) Shakespeare’s sublime poetry had been sullied by the over-literal hands of these impertinent, vulgar Yanks. A more charitable eye might have perceived that the artists and craftsmen behind the screen understood and honored that poetry, and were doing their best to render it faithfully in the visual medium that was their own area of expertise.

For the Hollywood Bowl production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream that so captivated Hal Wallis and thousands of other Angelenos, Reinhardt had moved away from the minimalist staging that he had been trending toward in Shakespeare’s forest revel (and which has more or less been followed ever since). In such a setting, a bare stage and simple green curtains would hardly do, so Reinhardt had transformed the play into a spectacular, awe-inspiring pageant. Or rather, transformed it back, for that was what the 19th century had seen in the play at least ever since 1843, when a German production in Potsdam first incorporated Felix Mendelssohn’s grandly romantic incidental music.

Scott MacQueen’s commentary on the DVD goes far to address the need for a full account of the making of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (though I still say it rates a book), but he offers only scattered details of the Bowl production which begot it. To my knowledge, no pictures from that staging are readily available, so I can’t address how the movie might have emulated or departed from it. There is, however, a certain semi-Wagnerian, almost Teutonic grandeur to the movie that is in keeping with what we know of Reinhardt’s style, and reviewers who saw his stage productions in L.A., New York and London recognized his touch on the screen. Whether direct credit for the final look of the movie goes to Prof. Reinhardt or to a combination of art director Anton Grot, set designer Harper Goff, costumer Max Ree, cinematographer Hal Mohr and editor Ralph Dawson (who won the movie’s other Oscar), it’s clear that the headline “A Max Reinhardt Production” was no empty boast.

The Hollywood Bowl had freed Reinhardt from the limitations of the ordinary proscenium stage. The movie screen freed him from the limitations of even that vast basin in the Hollywood Hills. As it happened, the camera ventured outside the sound stages only for this brief scene, where you can see the familiar hills of the Cahuenga Pass behind the studio’s backlot. But other freedoms came with the camera, and Reinhardt and co-director William Dieterle drew on the talents of Mohr and special effects team Byron Haskin, Fred Jackman and Hans Koenekamp to do things impossible on any stage.

The Hollywood Bowl had freed Reinhardt from the limitations of the ordinary proscenium stage. The movie screen freed him from the limitations of even that vast basin in the Hollywood Hills. As it happened, the camera ventured outside the sound stages only for this brief scene, where you can see the familiar hills of the Cahuenga Pass behind the studio’s backlot. But other freedoms came with the camera, and Reinhardt and co-director William Dieterle drew on the talents of Mohr and special effects team Byron Haskin, Fred Jackman and Hans Koenekamp to do things impossible on any stage. Like this, for instance. Here the followers of fairy queen Titania gather for their nightly revels, prancing, dancing, swirling and flying to the sprightly strains of Mendelssohn’s Scherzo as scored by Erich Wolfgang Korngold. (Korngold was imported by Reinhardt from their native Austria to arrange Midsummer‘s music; he would stay in Burbank to do other work for Warner Bros. Then, on the heels of Hitler’s annexation of Austria, Korngold would settle in Hollywood permanently, composing some of the greatest film scores of all time.) In the droll words of The New Yorker’s John Mosher, “The Reinhardt fairies flit over the treetops on escalators of moonshine, mists rise from the meadows and take the shapes of weird creatures of the night…” Shakespeare himself (as we can infer from the text of his plays) had a keen appreciation for the power of theatrical effects; would he not have reveled in these scenes as much as Titania’s fairies do? I believe he would have, and that anyone who thinks otherwise is a snob beyond redemption.

Like this, for instance. Here the followers of fairy queen Titania gather for their nightly revels, prancing, dancing, swirling and flying to the sprightly strains of Mendelssohn’s Scherzo as scored by Erich Wolfgang Korngold. (Korngold was imported by Reinhardt from their native Austria to arrange Midsummer‘s music; he would stay in Burbank to do other work for Warner Bros. Then, on the heels of Hitler’s annexation of Austria, Korngold would settle in Hollywood permanently, composing some of the greatest film scores of all time.) In the droll words of The New Yorker’s John Mosher, “The Reinhardt fairies flit over the treetops on escalators of moonshine, mists rise from the meadows and take the shapes of weird creatures of the night…” Shakespeare himself (as we can infer from the text of his plays) had a keen appreciation for the power of theatrical effects; would he not have reveled in these scenes as much as Titania’s fairies do? I believe he would have, and that anyone who thinks otherwise is a snob beyond redemption.

…minces…

…and pouts, in easily the worst performance of his career, and arguably one of the worst in Hollywood history. Powell was already chafing at his boy-tenor roles, sensing that the clock was ticking — on stage a male ingenue might keep it going until his grandkids were out of knee pants and pinafores, but in the movies it would never work, and at 30 Powell’s juvenile days were clearly numbered. Well then, playing Lysander in A Midsummer Night’s Dream was a heaven-sent opportunity for Powell to segue nimbly from squiring Ruby Keeler and Wini Shaw around Buzz Berkeley’s dance floors into the kind of roles where he could age with grace. But did he see it that way? He did not. Insisting he wasn’t “a Shakespearean actor,” he tried to dodge the role (some say “to his credit,” but I’d say it does him none; never mind “Shakespearean,” whatever that means; do you want to act or don’t you?). When the studio wouldn’t let him take a pass, he seems to have gone out of his way to prove how wrong they were. Obviously he didn’t think that one through; when the projector beam finally hit the screen in October 1935, it wasn’t Jack Warner or Hal Wallis up there with egg on his face. When Powell finally managed to carve out a new screen persona for himself in 1944’s Murder, My Sweet, I wonder: did he ever look back on the chance he had blown nine years earlier?

We can contrast Powell’s tantrum of a performance with another Midsummer actor who was miscast yet still managed to make it work: James Cagney. He’s the last actor you’d expect to play the lumpen dullard Nick Bottom, and he was apparently one of the last considered. Dieterle’s early notes mention Wallace Beery and W.C. Fields. Beery was a logical choice, if he could keep from dawdling through his lines and overdoing the neck-scratching mannerism he liked to use instead of acting — and if anyone on the set could have stood working with him (it certainly would have strained Anita Louise’s talent to the limit). Fields might have been fun, but the idea was a nonstarter — he was shooting David Copperfield over at MGM. Memos from Hal Wallis say what a “far-fetched” choice Cagney would be, and as late as the day before rehearsals started, contract player Guy Kibbee was slated for the role. But Reinhardt made an executive decision and Kibbee was out, Cagney in.

Fifty-two-year old Guy Kibbee would have been a comfortable choice for Bottom — a little old, maybe, but the right physical and character type — and he probably would have passed muster with the critics (except those in England who sniffed that there were just too damn many American accents in the cast). But Reinhardt was impressed with Cagney’s dynamism and the studio was comfortable with his box office clout (he did get top billing), so that was that. Cagney’s approach was straightforward — “The keynote,” he recalled decades later, “was the sonofabitch was a ham…he wanted to play all the parts…” He played Bottom as cocky and obnoxious rather than sluggish and obstinate; he made the character work for him, and made his performance work for Reinhardt and the movie. It’s not exactly the Bottom of Shakespeare, and in the movie it’s not entirely incongruous for Titania to fall for him, even crowned with a donkey’s head. But faced with the fait accompli of his casting, Cagney rolled up his sleeves and got to work. It was an attitude Dick Powell could have learned from, if he’d pulled in his lower lip long enough to take notice.

One facet of the movie that I’ve seen no comment on, but that keeps it living and breathing today, is its undercurrent of discreet eroticism. Nothing to put the bluenoses of the Hays Office out of joint, to be sure, but it’s there all the same. Here, for example, is the on-screen equivalent of that posed publicity shot of Titania and Bottom that I showed in Part 1. Not only is the pose more explicitly sexual, but so is the expression on Titania’s face. In the publicity still she stares blankly past Bottom’s snout, while here — in action, as it were — she gazes at him with a postcoital afterglow worthy of Scarlett O’Hara.

And here we are again with Hermia, as she contemplates eloping to beyond the forest with her true love Lysander. In 18-year-old Olivia de Havilland’s first screen performance, Hermia is proper and maidenly, but we see moments like this, flashes of the wanton under her decorous exterior. It makes the transition ring true later, as Puck’s mischievous love potion takes effect on Lysander, when Hermia becomes a snarling spitfire, seething with all the fury and sexual frustration of a woman scorned.

Notwithstanding the Neo-Victorian pageantry of the movie, there’s one way in which Reinhardt and Dieterle look not back to the past, but forward to later directors’ approach to A Midsummer Night’s Dream: they treat the quartet of young lovers not as the lyrical ideals they had become in the 19th century, but as foolish figures of fun, and the squabbling and bickering of this romantic quadrangle are some of the funniest scenes in the movie. Love’s unpredictable magic has turned them all into asses — a neat counterpoint to the story of Nick Bottom, where being changed into an ass unexpectedly turns him into a lover. Again, is that counterpoint explicitly to be found in Shakespeare? Perhaps not. But is it an astute comment on the intertwined stories of the Dream? Definitely. And it shows (again) an acute understanding of the material running all through the Warner lot in Burbank, not (as some critics then and now would have it) a blundering blindness to the beauty of what they were manhandling in their clumsy paws.

So returning to Scott MacQueen’s question — no, this was not the flowering of Shakespeare’s art, although it came closer to it than anyone could have expected. But “a sign that the Day of the Locust was at hand”? Hardly. For that, we need look no further than the 1930 Moby Dick, when Warner Bros. thoughtfully corrected the oversights of Herman Melville by providing Captain Ahab with a last name, a sweetheart, and a happy ending.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream may well be the most miraculous of those “miracle pictures” I wrote about before. Warner Bros. and Max Reinhardt undertook one of Shakespeare’s most beloved plays — not to “improve” or “correct” it, as Warners had tried with Moby Dick, but to fulfill it. Hal Wallis saw something at that amphitheater on Highland Avenue that struck him as worth putting on film, and whatever changes were wrought between the Bowl and Burbank, Wallis and his colleagues did their best to get it right. Let the salesmen worry about getting audiences into the theaters.

I conclude this tribute with a salute to three of the players from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the three members of the Hollywood Bowl cast who Max Reinhardt absolutely insisted must be included in the movie. By a happy coincidence, they are also the last three survivors of the principal players. Top to bottom: Mickey Rooney as Puck, Olivia de Havilland as Hermia, and Nini Theilade as chief fairy-in-waiting to Queen Titania.

Rooney and de Havilland hardly need any introduction. De Havilland, not only for her double-Oscar career but for her landmark lawsuit that eventually broke the studios’ iron slaveholder’s grip on their performing artists, may have proven to be Max Reinhardt’s most momentous contribution to movie history.

Nini Theilade, however, is a less familiar name. Born in Indonesia to Danish parents, she was 19 when she danced for Reinhardt at the Bowl, and for Dieterle and choreographer Bronislava Nijinska on the Warner Bros. sound stages. When Midsummer went from its road show to general release, 16 minutes were trimmed; since her performance was almost entirely danced, she was left with only a brief moment of dialogue with Rooney’s Puck. It took the restoration of the complete movie in 1994 to let us again see Mlle. Theilade’s full work, and appreciate her ethereal beauty and exquisite grace. She turned 95 on June 15, while de Havilland was 94 on July 1 and Rooney will turn 90 September 23. Continued long life to them all, and thanks.

UPDATE 9/5/16: Mickey Rooney passed away April 6, 2014, age 93. But I’m pleased to report that as of this date Ms. de Havilland and Mlle. Theilade are still with us, having turned (respectively) 100 on July 1 and 101 on June 15 of this year.

UPDATE 4/15/18: Mlle. Nini Theilade left us on February 13, 2018, just past the halfway mark to her 103rd birthday. Olivia de Havilland, 101, is now the last survivor of Warner’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream — and, in all likelihood, of the Golden Age of Hollywood.

UPDATE 8/11/20: And now, Olivia de Havilland is gone too, having passed away July 26, 2020, twenty-five days after her 104th birthday. May she, and the rest of the Midsummer cast, rest in peace, with the thanks of us all.