Catting Around

INTRODUCTORY NOTE: I wish I could take credit for this post, but I can’t. For the first time since I began Cinedrome, I’m presenting a guest blogger. The writer was a student in my Fall 2018 Introduction to Film Studies class at the college where I’m an adjunct instructor in Film and Media Studies. As I tell my Intro to Film students, my philosophy is that the best way to introduce them to film is to introduce them to films; thus I prefer to show them complete movies rather than excerpts. It’s all well and good to study individual sequences from movies you’ve seen, but if you haven’t seen the movie, showing part of it is like handing you a quarter-cup of Hershey’s Cocoa and calling it fudge.

In an 80-minute class period, finding movies to screen can be a challenge. So a major component of the class is to spend time with the films of Val Lewton, the legendary producer who turned out a series of extraordinarily intelligent B horror movies at RKO Radio during the 1940s — all of which ran between 65 and 75 minutes. An essay assignment on the final exam asked students to analyze any two of the five Lewton pictures they saw in class.

One student answered that assignment with a remarkable piece of film criticism, one of the best commentaries on Lewton’s unique body of work that I’ve ever read. I present that essay here for the enjoyment (and enlightenment) of Cinedrome readers.

I think it’s best if I don’t identify the student by name, or even by gender. Still, a few anonymous details won’t be out of order. This was the student’s first semester of college. He/she took the class “to learn more about the way movies/music videos/TV shows are made” and named some favorite movies: Roman Holiday, 10 Things I Hate About You, Lady Bird. The student has seen King Kong (1933), Gone With the Wind, West Side Story (1961), The Sound of Music and Schindler’s List, but not Citizen Kane, Dr. Strangelove or Pulp Fiction; has seen the first installment of The Lord of the Rings but not the second or third.

And with that, here is the essay prompt from the exam, followed by the student’s essay. I have corrected minor errors of spelling, grammar and punctuation, and added actors’ names in parentheses where appropriate; otherwise I’ve changed nothing.

* * *

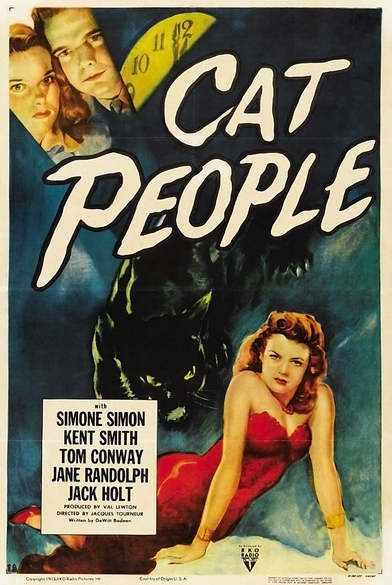

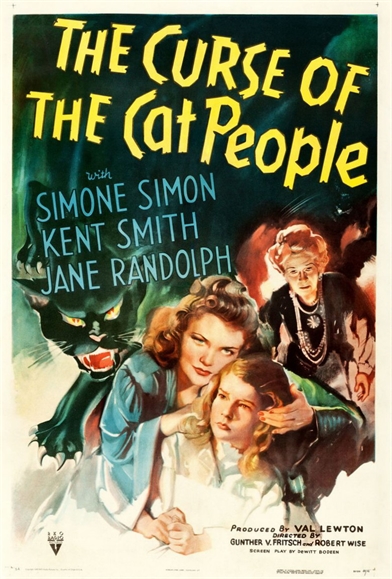

Producer Val Lewton was noted for his “psychological” horror movies, replacing the usual movie vampires, werewolves and other monsters with explorations of the darker reaches of the human psyche. We saw five of Lewton’s movies in class: Cat People (1942, d: Jacques Tourneur), I Walked with a Zombie (1943, d: Tourneur), The Curse of the Cat People (1944, d: Gunther von Fritsch, Robert Wise), The Body Snatcher (1945, d: Wise) and Isle of the Dead (1945, d: Mark Robson). Discuss the psychological aspects of any two of these films.

Producer Val Lewton was noted for his “psychological” horror movies, replacing the usual movie vampires, werewolves and other monsters with explorations of the darker reaches of the human psyche. We saw five of Lewton’s movies in class: Cat People (1942, d: Jacques Tourneur), I Walked with a Zombie (1943, d: Tourneur), The Curse of the Cat People (1944, d: Gunther von Fritsch, Robert Wise), The Body Snatcher (1945, d: Wise) and Isle of the Dead (1945, d: Mark Robson). Discuss the psychological aspects of any two of these films.

Val Lewton’s movies were known for having supernatural aspects, yet always ending with the common message that the evils of the world were not found in monstrous identities, but in humans themselves. In Cat People (1942) and The Curse of the Cat People (1944), both movies are heavy with psychological themes and explore individuals on a deeper level.

In Cat People the story is of a young man, Oliver (Kent Smith), falling for a mysterious designer named Irena (Simone Simon). Irena is reserved, and tells her husband there are certain things he cannot do, like kiss her. She is fearful of her past, which she hides from him, and is terribly afraid that she will turn into a monstrous cat that will put everyone around her in danger. She asks her husband to listen to her and to believe her when she finally confesses, but he brushes this off and makes her go see a therapist, Dr. Judd (Tom Conway). Irena wants to get better, but in the end, because her husband gives up on her and has an affair with his co-worker Alice (Jane Randolph), she turns into a large creature, is stabbed by Dr. Judd, who only wanted to exploit her, and dies.

The entire premise of Cat People seems to be a metaphor for depression or bipolar disorder, some type of mental illness. Irena suffers from a disorder due to a past that has traumatized her, and when she finally believes she can trust and open up to someone, they completely shut her down and refuse to understand her or stay with her through her episodes of unstable behavior. Throughout the film, Irena struggles with her ability to turn into a cat, much like those who suffer from mental illness. She has breakdowns and tries desperately to become better for the good of herself and her husband, but her husband gives up on her, triggering the start of another episode she cannot escape.

Irena has spent her whole life trying to suppress her emotions and “dark” feelings because that is what she has learned to do, which is unhealthy; this becomes her downfall in a way. Instead of being nurtured, encouraged, or listened to, Irena is forced to live in a cage her entire life, feeling as though she cannot escape from the prison of her mind. When she dies, she is finally free from the evils that plague her.

Irena has spent her whole life trying to suppress her emotions and “dark” feelings because that is what she has learned to do, which is unhealthy; this becomes her downfall in a way. Instead of being nurtured, encouraged, or listened to, Irena is forced to live in a cage her entire life, feeling as though she cannot escape from the prison of her mind. When she dies, she is finally free from the evils that plague her.

In truth, Irena was not the villain of the film at all. Oliver and Dr. Judd played such a large part in her downfall. Her husband, for not choosing to stick with her through the worst of times, and her therapist for trying to exploit her circumstances for his own curiosity, not to actually help her — which reflects many issues surrounding mental health today. Those afflicted with illness such as depression, etc., are not always supported and treated properly or given the help they need. When Lewton produced Cat People he chose a very taboo subject at the time and disguised it with a “horror” aspect. But Cat People seems to be a reflection of and metaphor for how mental illness works and affects people negatively.

Furthermore, in The Curse of the Cat People, the sequel to Cat People, we see Irena’s husband Oliver is now married to his co-worker Alice, and has a daughter with her named Amy (Ann Carter). Amy is perceived as a strange, imaginative girl who daydreams about fantastical and magical things. The other children believe her to be weird because of her airy personality and short attention span. She later befriends an old lady, Mrs. Farren (Julia Dean), with a jealous daughter Barbara (Elizabeth Russell), and even creates an imaginary friend who takes the form of Irena, her father’s first wife. Again, instead of choosing to understand his daughter, Oliver firmly tells her she must go play with the other kids or she will be punished. He also condemns her for having an imaginary friend, and she is severly punished for that as well.

Furthermore, in The Curse of the Cat People, the sequel to Cat People, we see Irena’s husband Oliver is now married to his co-worker Alice, and has a daughter with her named Amy (Ann Carter). Amy is perceived as a strange, imaginative girl who daydreams about fantastical and magical things. The other children believe her to be weird because of her airy personality and short attention span. She later befriends an old lady, Mrs. Farren (Julia Dean), with a jealous daughter Barbara (Elizabeth Russell), and even creates an imaginary friend who takes the form of Irena, her father’s first wife. Again, instead of choosing to understand his daughter, Oliver firmly tells her she must go play with the other kids or she will be punished. He also condemns her for having an imaginary friend, and she is severly punished for that as well.

Amy’s imaginary version of Irena is everything her parents are not — she listens to Amy, encourages and nurtures her, and therefore perpetuates Amy’s innocent view of the world in which all life is beautiful.

Amy’s childish innocence and ability to spread her warmth saves her from being killed when she hugs Mrs. Farren’s bitter daughter Barbara — Amy can see the good in people and in everything due to her innocence. In the end, Amy’s parents believe in her and finally listen to her instead of forcing her to try to be “normal” like the other children.

This here is another example of Lewton using a supernatural aspect as a disguise for a subject that was not really brought up during this time. Amy is a child who seems to be on the autism spectrum; she appears to have Asperger syndrome due to her behavior. Instead of really assessing this fact in their daughter, Amy’s parents, especially Oliver, are intent on making her a “normal” child, even punishing her for silly issues such as having an imaginary friend. Both parents are fearful their child may be mentally ill, especially when Amy mentions Irena. But in the end they come to accept her and foster her growth rather than cage her up, which is a stark contrast to what they did with Irena. The supernatural aspect Lewton added was to keep up the theme of “horror” films the company was marketing his movies as, but Curse of the Cat People was truly about child-like innocence and how adults try to take it away at an early age, when really they should be enouraging it.

Both Cat People and The Curse of the Cat People deal with serious issues in the world, but each topic is thinly veiled behind a supernatural aspect. Val Lewton’s films, though not filled with scary entities to haunt your dreams, are still equally as terrifying as they reflect how humans work. The psychological aspects of his films are what truly make them memorable and frightening.

* * *

This is Jim again — I’m back. I don’t mind saying that this essay left me gasping with admiration. I don’t think I could have answered the essay prompt as completely and concisely as this student did — and I made it up. And remember: the student wrote this, as it were, “under the gun”, in a two-hour exam period — and after writing an equally long and insightful essay comparing Buster Keaton’s The General (1926) and Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928).

The mention of Amy possibly having Asperger syndrome is particularly astute — especially since the student is probably too young to know that Asperger’s had barely been identified by 1944 (and then only in the Third Reich) and didn’t become general knowledge until the 1980s. (Of course, behavior like Amy’s was not unheard of back then, but it was usually described in less compassionate terms: “The kid’s weird / nuts / not right in the head…”) In other classes where I screened Curse of the Cat People, I discussed the idea of Amy’s being somewhere on the autism spectrum (itself barely recognized in ’44), but with this class I didn’t. As it happened, I didn’t have to — not for this student, anyhow.