Wyler Catches Fire: Hell’s Heroes

July 1 will mark the 110th anniversary of the birth of William Wyler (1902-81), peerless movie director par excellence. The occasion is being observed by a blogathon hosted by The Movie Projector over the next six days, in which many of my fellow members in the Classic Movie Blog Association (CMBA) will be holding forth on their favorite Wyler pictures. Go here for a list of blogathon participants and links to their individual posts as they go up.

For my part, in conjunction with The Movie Projector’s blogathon, I’m republishing a series of five posts I did on Wyler in 2010, one a day for five of the six days of the blogathon. Happy Birthday, Willy, and thanks for the memories!

* * *

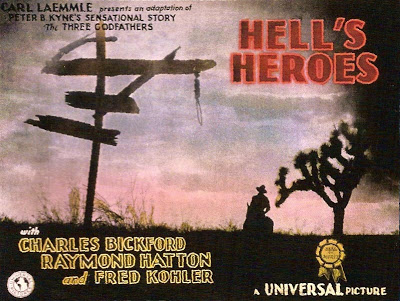

In his biography of William Wyler, A Talent for Trouble, author Jan Herman makes the kind of statement movie buffs love to see become obsolete: “There are no extant prints of the sound version of Hell’s Heroes.” Herman then goes on to discuss Wyler’s first talkie in terms of its silent version (like many early sound pictures, Hell’s Heroes was released silent as well, for theaters that had not yet been wired for sound).

A Talent for Trouble was published seventeen years ago, and I’m sure Herman himself is pleased to know that his pronouncement is no longer operative. Fortunately for us, Hell’s Heroes was remade by MGM in 1936 under author Peter B. Kyne’s original title Three Godfathers (and again in 1948 as 3 Godfathers, that time directed by John Ford and starring Duke Wayne), so ownership of this Universal picture devolved upon Metro.

In those days, when Metro remade a movie, it was studio practice to buy up and suppress (some say destroy) any earlier versions. If those originals were in fact earmarked for the incinerator, we probably have a fumbling studio bureaucracy to thank for the fact that we can still see Paramount’s 1932 Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Universal’s 1936 Show Boat, the British Gaslight of 1940, even MGM’s own silent Ben-Hur, and other movies that the suits at the Tiffany Studio took it into their heads to remount over the years.

We can certainly thank MGM’s acquisitiveness for the fact that these titles from other studios ended up in the MGM library and are now owned by Warner Home Video. The Warner Archive offers a double-feature package of Hell’s Heroes with MGM’s 1936 remake, and it affords us an opportunity to appreciate this landmark in William Wyler’s career that wasn’t available to Jan Herman in 1995.

To direct the new version of the story, Laemmle chose 27-year-old William Wyler. Wyler had begun work on the Universal City lot as an errand boy, and after a rocky start — at one point studio chief Irving Thalberg dubbed him “Worthless Willy” — Wyler had risen to where he was considered an asset to the studio. Hell’s Heroes was to be his first talkie, but he was no stranger to westerns, having cut his directorial teeth on them from 1925 on — first a series of nearly two dozen two-reel horse operas for Universal’s so-called “Mustang” unit, then five-reel features in the “Blue Streak” series.

Bodie was near the tail-end of its boom-and-bust history in the late summer of 1929. Originally founded on a nearby gold strike in 1859, it had grown by 1880 to a reported population of 10,000, home to 65 saloons and other establishments of ill repute. By 1929 the population hovered around 100. Three years after the Hell’s Heroes crew left town, so the story goes, a young boy at a church social threw a tantrum when he was given Jell-O instead of ice cream. Sent home as a punishment, he set fire to his bed and burned down over 90 percent of the town. The final blow came in 1942, when War Production Board Order L-208 closed down all nonessential gold mines in the country, including Bodie’s; even the U.S. Post Office closed. Today, what’s left of Bodie is a California State Park and a National Historic Landmark.

Notwithstanding the efforts of that youthful Depression-Era pyromaniac, traces of Bodie as it appears in Hell’s Heroes survive to the present day. Here’s Bodie’s Methodist Church, which figures prominently in the movie’s opening and closing scenes, as it appears today.

And here it is again, on the left edge of the frame, at the top of Bodie’s — er, that is, New Jerusalem’s — dusty main street.

… and a similar view taken more recently, showing what’s left of the same street.

Hell’s Heroes was a success for Universal and for Wyler personally. He’d become an asset to Universal for his westerns, but outside the studio Universal’s westerns — cranked out in days for small-time houses in neighborhoods and farm towns — hardly deserved notice. Now people were noticing. Over at Warner Bros., Darryl F. Zanuck ordered all his producers to see “this picture by this new director.”

What specifically excited Zanuck was a tracking shot that Wyler inserted as a way to sidestep a conflict with his leading man, Charles Bickford (on the right in this picture; the others are Raymond Hatton, left, and Fred Kohler). Bickford was a recent import from Broadway — Heroes was his third picture, made and released hot on the heels of the other two — and he evidently didn’t cotton much to being directed by some Hollywood rube who didn’t know anything about real acting. Herman tells us he even went out of his way to undermine Wyler with his fellow actors, an unconscionable breach of protocol then, and an actionable offense under union rules now.

Their particular conflict came over a scene late in the movie as Bickford, the last survivor of the three bandits, trudges through the desert with the baby in his arms. Wyler wanted Bickford, carrying a rifle as well as the child, to first drop the butt-end of the rifle in the dust and drag it for a distance before dropping it altogether. Bickford refused. He insisted on stopping in his tracks, looking at the rifle, then hurling it away from him into the dirt.

I almost wish this shot survived in the Universal vaults; I’d love to see it, because it sounds perfectly ridiculous — just the kind of grandiloquent gesture you’d expect from a stage-trained ham with a lot to learn about movie acting. A man dying of thirst won’t be able to summon the strength to throw a heavy rifle at all — and besides, shooting the scene in a real desert, he’d have to throw it about a hundred yards before it looked as impressive to the camera as the actor doing it thought it did.

Wyler’s solution was ingeniously simple. He filmed the scene the way Bickford wanted to play it. Then, one day when Bickford wasn’t on call, he dressed a prop man in Bickford’s boots, had him make tracks in the desert sand, and photographed them with a moving camera.

First we see just the bandit’s footprints, occasionally staggering and shuffling…

…then the tracks and the divot dug by the rifle butt…

“The Best of Us”, Part 1

* * *

True, it’s hard to believe that the director of the bloated, lumbering Ben-Hur is the same man, 20-plus years on, who turned out the spare, gritty Hell’s Heroes or the trifling, light-hearted confection The Good Fairy with Margaret Sullavan (who became, for a scant sixteen months, his first wife), never mind anything in between. Wyler’s career doesn’t have to stand on Ben-Hur, nor does it deserve to fall on it.

I have an idea for a book, and I may yet do it: The Movie Directors’ Hall of Fame. The idea is this: create a scoring system for directors, compiling statistics the way they do for professional athletes. Award so many points for winning an Oscar, so many for directing an Oscar-winning best picture, for directing an Oscar-winning or nominated performance, for directing one of the top box-office movies of the year, for winning the DGA or other directing awards, and so on. Total up the points and see how things shake out.

To be continued…

“The Best of Us”, Part 2

July 1 will mark the 110th anniversary of the birth of William Wyler (1902-81), peerless movie director par excellence. The occasion is being observed by a blogathon hosted by The Movie Projector June 24 – 29, in which many of my fellow members in the Classic Movie Blog Association (CMBA) will be holding forth on their favorite Wyler pictures. Go here for a list of blogathon participants and links to their individual posts as they go up.

* * *

Thalberg called him “Worthless Willy.” This surely makes William Wyler the only recipient of the Academy’s Irving G. Thalberg Award to have been publicly disparaged by the man the award was named for.

Thalberg did have his reasons. Only three years older than Wyler, he was far beyond him in stature at Universal when Wyler started there as an errand boy in 1921. According to Wyler’s biographer Jan Herman, the only time Universal’s youthful production chief deigned to notice the 19-year-old Wyler, it didn’t go well for the future director. “You read German, don’t you?” Thalberg asked. Wyler, fairly fresh from Europe and still honing the command of English he’d begun developing there, said he did. Thalberg handed him a German novel, a property the studio was considering buying for director Erich von Stroheim. “Bring me a synopsis in English on Monday.”

This was on Friday, and Wyler didn’t make the deadline; he didn’t even finish the book. Monday came, then Tuesday and Wednesday before he could even tell Thalberg what the book was about; he appears never to have done a written synopsis. It also appears that Thalberg was administering a test — and Wyler flunked. In any case, Wyler — young and unfocused — never got another personal assignment, however trivial, from Thalberg. The “Worthless” moniker came along later, when Thalberg got wind of the teenager’s arrests for reckless driving; Thalberg must have decided the kid would never amount to much.

If so, then Thalberg, who died at 37, lived just long enough to get an inkling of how wrong he was. Even by the time Thalberg left Universal in 1924 for the new-minted super-studio MGM, Worthless Willy had already amounted to an assistant director — of sorts. On The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), Thalberg’s pet project at Universal, Wyler was still just an errand boy, but now he was running errands for assistant directors Jack Sullivan and Jimmy Dugan, wrangling the picture’s thousands of extras and getting his first chance to wield the coveted megaphone.

The anecdote of the German novel is a telling one. Wyler may have been a slow starter at Universal, and may have struck higher-ups — and in those days nearly everybody at Universal was higher up than he was — as a bad bet, but he was already showing a trait that would follow him all through his career: Willy Wyler didn’t like to be hurried. In time, the “Worthless Willy” nickname would give way to another: “90-Take Wyler.”

Charlton Heston on Ben-Hur, for example. One night, he said, Wyler came to him in his dressing room. “Chuck, you gotta be better in this picture.”

Nonplussed, Heston said, “Okay. What can I do?”

“I don’t know. I wish I did. If I knew, I’d tell you, and you’d do it, and that would be fine. But I don’t know.”

“That was very tough,” Heston recalled. “I spent a long time with a glass of scotch in my hand after that.”

Wyler, it seems, didn’t always issue instructions like a recipe to his actors. But he knew what he wanted. And he knew that “I’ll know it when I see it.”

These anecdotes conjure an image of a director passively waiting for lightning to strike, and willing to spend any amount of time and his producer’s money while he waited. What they don’t suggest is the process his refusal to accept the merely adequate sparked in his actors and writers. On their first picture together, The Big Country, Heston took exception to some minor piece of Wyler’s direction and wanted to discuss it. He didn’t have his script handy, so he asked to borrow Wyler’s.

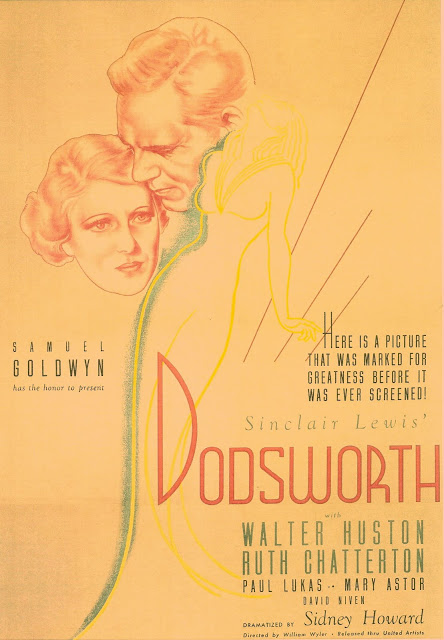

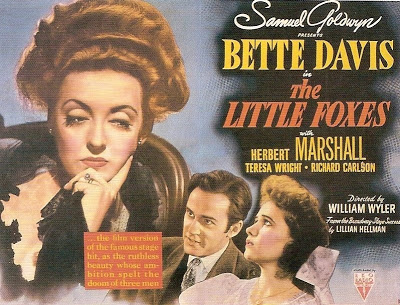

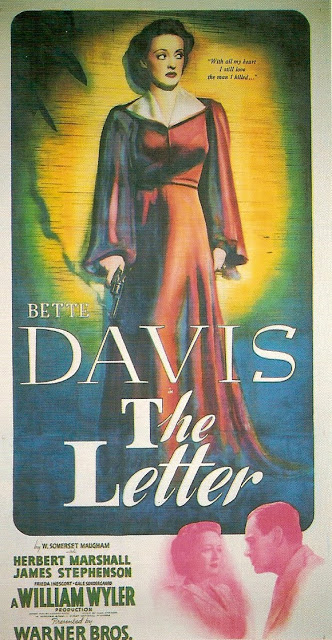

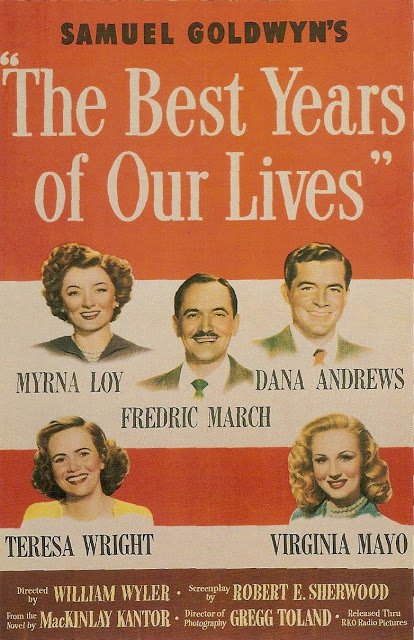

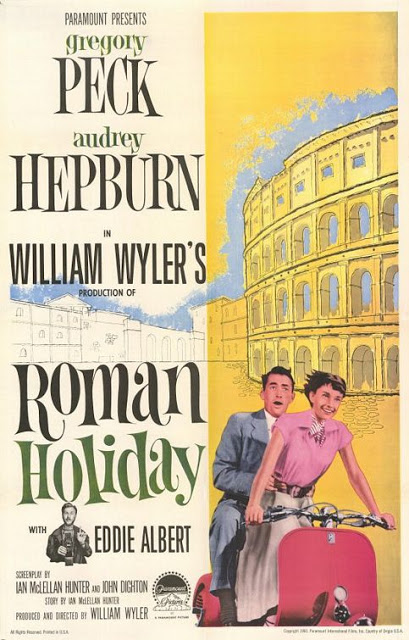

Wyler always carried his script in a leather binder, with the titles of his movies engraved in gold inside the front cover; when he finished a picture, he’d take the script out, engrave that one’s title on the cover and move on to the next. As Heston took Wyler’s script, it flipped open to the inside cover and he saw the titles engraved there: Dodsworth, Dead End, Jezebel, Wuthering Heights, The Letter, The Westerner, The Little Foxes, Mrs. Miniver, The Best Years of Our Lives, The Heiress, Detective Story, Roman Holiday…

As Heston stared, Wyler grew impatient. “What is it, Chuck? What’s on your mind?”

Heston closed the script and handed it back. “Never mind, Willy. It’s not important.”

Wyler began directing on two- and five-reel westerns at Universal, where they didn’t want it good, they wanted it Thursday afternoon. The formulas were simple and unsubtle, and the movies had to move. Wyler showed, in now-forgotten titles like Ridin’ for Love, Gun Justice and Straight Shootin’, that he could turn it in Thursday afternoon and good. As the importance of his assignments increased, he drew on his bosses’ memory of how right he had gotten things before — under the gun, with the front office relentlessly beancounting — to take more time and money to get it exactly right this time. And as his reputation grew (and stayed with him nearly to the end) as a man who couldn’t make a flop, the people who worked with him tended more and more to take his word, like Heston on The Big Country and Ben-Hur. If Willy thinks I can do better, he must be right, and it’s up to me to figure out how.

When a director insists on take after take, saying nothing but “again” and “it stinks,” an actor’s response is usually to think (or say), “This guy’s giving me nothing, and he’s a tyrant to boot.” And some did. Jean Simmons worked for Wyler on The Big Country (1958), and even thirty years later she declined to discuss the experience with Jan Herman. Not so Sylvia Sidney, who dripped venom talking about doing Dead End fifty years after the fact. Ruth Chatterton didn’t wait that long; she was every inch the affronted diva on Dodsworth even as Wyler and producer Sam Goldwyn were trying to jumpstart her fading career (“Would you like me to leave the studio, Miss Chatterton?” “I would indeed, but unfortunately I’m afraid it can’t be arranged.”).

Whatever the truth of these situations, the point is what conspicuous exceptions Simmons, Sidney and Chatterton are among the legions of actors who worked with Wyler. The tales of his calling take after take are recounted with affection, not exasperation — not only by the Oscar winners, and not only years after wounded feelings have healed (Bette Davis got over her snit instantly). Wyler apparently never uttered the words “I know what I’m doing; trust me,” but that seems to be the effect he had on people. Combined with a powerful personal charm, he exuded an atmosphere of serene confidence on the set that made people want to please him, even as they struggled through twenty, thirty takes or more trying to figure out what the hell he wanted them to do. Wyler’s attitude was that they could do better; their response was to work all the harder to prove him right.

This is the intangible ingredient in Wyler’s pictures, along with the ones we can identify and point to: the bravura or simply spot-on-genuine performances, the incisive writing, the striking cinematography (Wyler worked seven times with the great Gregg Toland, and they brought out the best in each other), the handsome production designs. If you want to find the “personal element” in Wyler’s pictures, there it is: He had the confidence to take his time. In remarkably short order, thanks to luck as well as talent, he established a track record that allowed him to insist on it.

To be continued…

Wyler and “Goldwynitis” (reprinted)

* * *

For his part, Goldwyn complained that Wyler shot as if he owned stock in a film company. Part of the reason for all this is the fact that they were so much alike. They were both inarticulate, though each handled it in different ways. Goldwyn blustered and railed, shaking his fist at the top of his voice. Wyler didn’t; he just quietly ordered another take, saying little. Neither man could tell people exactly what he wanted, but each knew it when he finally saw it. In Goldwyn A. Scott Berg quotes Ben Hecht on the producer:

Ben Hecht wrote that Goldwyn as a collaborator was inarticulate but stimulating, that he “filled the room with wonderful panic and beat at your mind like a man in front of a slot machine, shaking it for a jackpot.”

To be concluded…

Wyler’s Legacy (reprinted)

July 1 will mark the 110th anniversary of the birth of William Wyler (1902-81), peerless movie director par excellence. The occasion is being observed by a blogathon hosted by The Movie Projector June 24 – 29, in which many of my fellow members in the Classic Movie Blog Association (CMBA) will be holding forth on their favorite Wyler pictures. Go here for a list of blogathon participants and links to their individual posts as they go up.

* * *

When I mentioned to a friend that I was planning a post on William Wyler (which has now turned into several), he said, “Good. I’ll be interested to see what you consider his…” — he searched for the right word — “…apotheosis.”

To tell the truth, at that point I hadn’t given much thought to apotheosizing the man, though I guess that’s what I’ve done. The dictionary gives two definitions of apotheosis: (1) the elevation of someone to the status of a god; and (2) the epitome or quintessence. So since my friend brought it up, what is, or was, the apotheosis of William Wyler? Now that I’ve elevated him to somewhere in the vicinity of godhood, what should we consider the epitome and quintessence of his work?

Mrs. Miniver was also a juggernaut in 1942, but that time the momentum was fueled by patriotism instead of studio hype. In this poster the exclamation point is appended to the claim “Voted the Greatest Movie Ever Made.” Whose votes were counted is left obscure, but there’s no denying that Miniver was beloved in its day, and its Oscar was similarly assured.

The picture began as unabashed pro-British propaganda in their war against Germany; it changed to pro-Allied propaganda when Pearl Harbor was attacked midway through production. Miniver‘s morale value was a real boon to the war effort, and it deserves points for fervent sincerity, but alas, it’s a museum piece today, with the same Hollywooden imitation-Englishness that besets MGM’s 1938 A Christmas Carol. (In Miniver‘s case, British audiences seemed not to mind, no doubt taking the intention for the deed.) Among its fellow best picture nominees, even the rampant flag-waving of Wake Island, The Pied Piper and Yankee Doodle Dandy wears better today. Add in The Invaders, Kings Row, The Pride of the Yankees, The Talk of the Town and The Magnificent Ambersons — and the case for Mrs. Miniver grows weaker with each title. Potent blow for righteousness that it was in its day, Miniver no longer has the ring of truth it had in 1942.

I use that phrase deliberately, because it brings to mind the first time I saw The Best Years of Our Lives, in the early ’70s when Sam Goldwyn had finally released at least some of his films to television. I watched Best Years one night with a friend, a conscientious objector then in the midst of grappling with his draft board at the height of the Vietnam War. As we watched the movie unfold, Wyler’s (and writers MacKinlay Kantor and Robert Sherwood’s, and producer Sam Goldwyn’s) story of three World War II vets struggling to readjust to civilian life, my pacifist-conscientious-objector-draft-dodger pal turned to me and said, “This still has the ring of truth, doesn’t it?”

So much for those three. But it’s a truism that people seldom win Oscars for their best work, and nobody illustrates the point better than William Wyler. To find his best work — his (ahem) apotheosis — I do think you have to look further than even the best of those three.

High on my short list — and right at the top, probably — would be the two pictures Wyler made on loan to Warner Bros. with Bette Davis. I’ve told the story of Jezebel and the 48 takes with the riding crop. Later on that same picture, when executive producer Hal Wallis made noises about firing Wyler for (what else?) wasting film and ordering too many takes, Davis went to bat for her director and saved his job, offering to work overtime if it would help (and only if they’d keep Wyler on).

True, she was having an affair with Wyler at the time, but she was a hard-nosed career woman who (if you’ll pardon the expression) never let the little head do the thinking for the big head. Whatever was going on during off-hours, she knew he was getting the performance of her life (so far) out of her, and was doing almost as much for others in the cast — George Brent and (of all people) Richard Cromwell were seldom as good, and never better.

He did almost as much on The Letter in 1940, two years later, and with a much better script (from the story by W. Somerset Maugham). Davis didn’t get the Oscar for this one, but she’s nearly as good as she was in Jezebel, showing the feral fang-and-claw passions roiling under a studied veneer of respectability. (The Wyler-Davis magic failed only on their third and final movie together, 1941’s The Little Foxes, and then only because the headstrong Davis wouldn’t listen to him. He wanted a more textured performance, but she insisted on going deep into Wicked Witch territory. Her two-dimensional approach wasn’t enough to sink the movie — Davis was always worth watching, no matter what — but it did allow the all-but-unthinkable: not one but two other performers, Charles Dingle and Patricia Collinge, stole the picture from her.)

So I guess my friend’s curiosity will have to remain unsatisfied, at least by me. I can’t name a single “apotheosis” for William Wyler, and even now I’ve probably left somebody’s favorite out; at least half a dozen other titles spring to mind without even trying. For me, there’s no single “elevation” of the man and his work; there are just too many peaks, like the Himalayas with a dozen Everests.