Wyler Catches Fire: Hell’s Heroes

July 1 will mark the 110th anniversary of the birth of William Wyler (1902-81), peerless movie director par excellence. The occasion is being observed by a blogathon hosted by The Movie Projector over the next six days, in which many of my fellow members in the Classic Movie Blog Association (CMBA) will be holding forth on their favorite Wyler pictures. Go here for a list of blogathon participants and links to their individual posts as they go up.

For my part, in conjunction with The Movie Projector’s blogathon, I’m republishing a series of five posts I did on Wyler in 2010, one a day for five of the six days of the blogathon. Happy Birthday, Willy, and thanks for the memories!

* * *

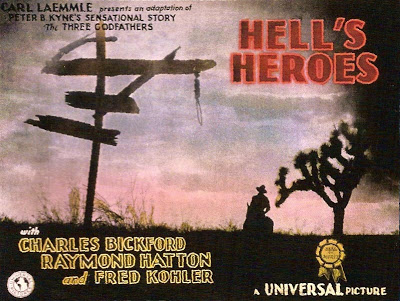

In his biography of William Wyler, A Talent for Trouble, author Jan Herman makes the kind of statement movie buffs love to see become obsolete: “There are no extant prints of the sound version of Hell’s Heroes.” Herman then goes on to discuss Wyler’s first talkie in terms of its silent version (like many early sound pictures, Hell’s Heroes was released silent as well, for theaters that had not yet been wired for sound).

A Talent for Trouble was published seventeen years ago, and I’m sure Herman himself is pleased to know that his pronouncement is no longer operative. Fortunately for us, Hell’s Heroes was remade by MGM in 1936 under author Peter B. Kyne’s original title Three Godfathers (and again in 1948 as 3 Godfathers, that time directed by John Ford and starring Duke Wayne), so ownership of this Universal picture devolved upon Metro.

In those days, when Metro remade a movie, it was studio practice to buy up and suppress (some say destroy) any earlier versions. If those originals were in fact earmarked for the incinerator, we probably have a fumbling studio bureaucracy to thank for the fact that we can still see Paramount’s 1932 Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Universal’s 1936 Show Boat, the British Gaslight of 1940, even MGM’s own silent Ben-Hur, and other movies that the suits at the Tiffany Studio took it into their heads to remount over the years.

We can certainly thank MGM’s acquisitiveness for the fact that these titles from other studios ended up in the MGM library and are now owned by Warner Home Video. The Warner Archive offers a double-feature package of Hell’s Heroes with MGM’s 1936 remake, and it affords us an opportunity to appreciate this landmark in William Wyler’s career that wasn’t available to Jan Herman in 1995.

To direct the new version of the story, Laemmle chose 27-year-old William Wyler. Wyler had begun work on the Universal City lot as an errand boy, and after a rocky start — at one point studio chief Irving Thalberg dubbed him “Worthless Willy” — Wyler had risen to where he was considered an asset to the studio. Hell’s Heroes was to be his first talkie, but he was no stranger to westerns, having cut his directorial teeth on them from 1925 on — first a series of nearly two dozen two-reel horse operas for Universal’s so-called “Mustang” unit, then five-reel features in the “Blue Streak” series.

Bodie was near the tail-end of its boom-and-bust history in the late summer of 1929. Originally founded on a nearby gold strike in 1859, it had grown by 1880 to a reported population of 10,000, home to 65 saloons and other establishments of ill repute. By 1929 the population hovered around 100. Three years after the Hell’s Heroes crew left town, so the story goes, a young boy at a church social threw a tantrum when he was given Jell-O instead of ice cream. Sent home as a punishment, he set fire to his bed and burned down over 90 percent of the town. The final blow came in 1942, when War Production Board Order L-208 closed down all nonessential gold mines in the country, including Bodie’s; even the U.S. Post Office closed. Today, what’s left of Bodie is a California State Park and a National Historic Landmark.

Notwithstanding the efforts of that youthful Depression-Era pyromaniac, traces of Bodie as it appears in Hell’s Heroes survive to the present day. Here’s Bodie’s Methodist Church, which figures prominently in the movie’s opening and closing scenes, as it appears today.

And here it is again, on the left edge of the frame, at the top of Bodie’s — er, that is, New Jerusalem’s — dusty main street.

… and a similar view taken more recently, showing what’s left of the same street.

Hell’s Heroes was a success for Universal and for Wyler personally. He’d become an asset to Universal for his westerns, but outside the studio Universal’s westerns — cranked out in days for small-time houses in neighborhoods and farm towns — hardly deserved notice. Now people were noticing. Over at Warner Bros., Darryl F. Zanuck ordered all his producers to see “this picture by this new director.”

What specifically excited Zanuck was a tracking shot that Wyler inserted as a way to sidestep a conflict with his leading man, Charles Bickford (on the right in this picture; the others are Raymond Hatton, left, and Fred Kohler). Bickford was a recent import from Broadway — Heroes was his third picture, made and released hot on the heels of the other two — and he evidently didn’t cotton much to being directed by some Hollywood rube who didn’t know anything about real acting. Herman tells us he even went out of his way to undermine Wyler with his fellow actors, an unconscionable breach of protocol then, and an actionable offense under union rules now.

Their particular conflict came over a scene late in the movie as Bickford, the last survivor of the three bandits, trudges through the desert with the baby in his arms. Wyler wanted Bickford, carrying a rifle as well as the child, to first drop the butt-end of the rifle in the dust and drag it for a distance before dropping it altogether. Bickford refused. He insisted on stopping in his tracks, looking at the rifle, then hurling it away from him into the dirt.

I almost wish this shot survived in the Universal vaults; I’d love to see it, because it sounds perfectly ridiculous — just the kind of grandiloquent gesture you’d expect from a stage-trained ham with a lot to learn about movie acting. A man dying of thirst won’t be able to summon the strength to throw a heavy rifle at all — and besides, shooting the scene in a real desert, he’d have to throw it about a hundred yards before it looked as impressive to the camera as the actor doing it thought it did.

Wyler’s solution was ingeniously simple. He filmed the scene the way Bickford wanted to play it. Then, one day when Bickford wasn’t on call, he dressed a prop man in Bickford’s boots, had him make tracks in the desert sand, and photographed them with a moving camera.

First we see just the bandit’s footprints, occasionally staggering and shuffling…

…then the tracks and the divot dug by the rifle butt…

I love this film! It has haunted me since I first saw it ten years ago: the awfulness, and yet the majesty of the desert were what attracted me at first. I love how the fluidity of a silent western (probably with some dubbing in the bank robbery scene) and the absolute starkness of an early sound film combine here so well. This makes the contemporaneous Virginian look like little better than a filmed play. Also, the dialogue, with a few completely genuine curse words (something that only the earliest sound films even have) makes this all the more stark.

I greatly enjoyed your post, Jim — I'd never even heard of this film before, but I'd like to check it out (even though I'm generally not a big western lover). I also appreciated your "then and now" pictures!