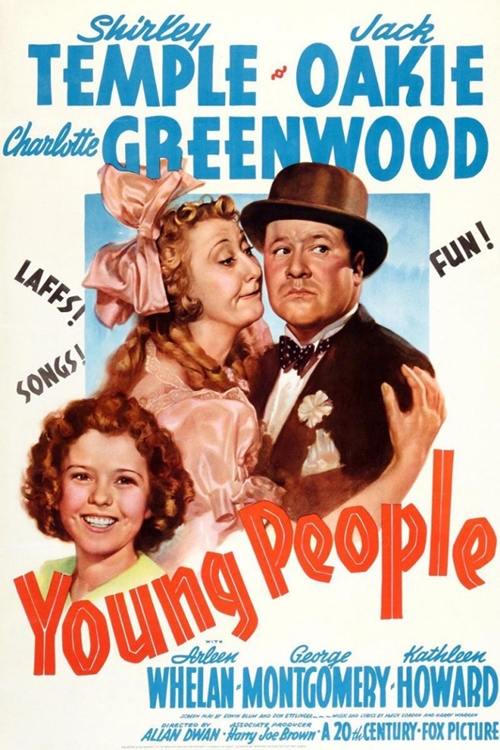

Bright Eyes, 1928-2014

It’s been over three weeks now since the news came that Shirley Temple Black had left us. I’ve spent the time perusing her 1988 autobiography Child Star — refreshingly frank and thorough, if a bit starchy and formal. I’ve also been reacquainting myself with her movies, which was more than a little overdue; I haven’t seen most of her pictures since I was about the age she was when she made them. Some I’ve never seen at all.

It’s been over three weeks now since the news came that Shirley Temple Black had left us. I’ve spent the time perusing her 1988 autobiography Child Star — refreshingly frank and thorough, if a bit starchy and formal. I’ve also been reacquainting myself with her movies, which was more than a little overdue; I haven’t seen most of her pictures since I was about the age she was when she made them. Some I’ve never seen at all.It may sound strange, but the comparison that sprang to my mind when I heard she was gone was with the Beatles, and not just because she appears in the crowd on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

And they went beyond merely breaking the mold. They reset it — in their own image. Pop idols from ABBA and the Bay City Rollers to One Direction and Justin Bieber would all be called the biggest thing since the Beatles, but there never was a “next” Beatles. It’s been 80 years since Shirley Temple’s bit part in Stand Up and Cheer! made America sit up and take notice, and from Jane Withers through Freddie Bartholomew, Roddy McDowall, Margaret O’Brien, Bobby Driscoll, Patty McCormack, Hayley Mills, Tatum O’Neal, Drew Barrymore, Abigail Breslin — plus countless sitcom kiddies sprouting up along the way — there’s never been a “next” Shirley Temple either.

Later, when — as it inevitably must — her box-office power began to wane, her personal popularity never did. Neither did the level-headed cheer that made up her on-and-off-screen personae. There was no descent into bitterness, drugs or alcohol, no pathetic scramble to cling to lost youth, no humiliating splash in the tabloids. A happy second marriage to well-to-do Charles Black helped, but even that might not have happened without the solid, no-nonsense upbringing she got from her mother.

Gertrude Temple was the kind of woman who could have given stage mothers a good name — if there hadn’t been so few like her. She saw to it that little Shirley had a firm sense of self independent of her phenomenal popularity — and in time, independent of her mother. That’s why, when her movie career ended in 1950, Shirley was able to move on without a backward glance. The grace, confidence and poise instilled by Mother Gertrude served her daughter well through those early dizzy years and, more important, long after. They took her smoothly through, first, a second career in early television; then, surprisingly, a third career in politics and international diplomacy, as U.S. ambassador to Ghana and Czechoslovakia and White House chief of protocol; and finally, a long bask in the setting sun as a Dowager Queen of the Golden Age of Hollywood.

I’ll have more to say about those first heady years in posts to come. For now: So long, Shirley, and thanks for the memories. We shall not look upon your like again.

.

Shirley Temple Revisited, Part 1

Shirley Temple got her feet wet in the movie business — and came to the attention of Fox Film Corp. — in Jack Hays’s “Baby Burlesks”. These were a bizarre series of shorts that pretty much have to be seen to be disbelieved. The basic idea was to show toddlers in diapers either spoofing famous movies or engaging in various grown-up activities: war, politics, making movies (although the series called into question exactly how grown-up that particular activity was). The first of these shorts — though the “Baby Burlesks” name hadn’t been adopted yet — was Runt Page, a send-up of Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur’s The Front Page. And this shot right here was America’s first look at three-year-old Shirley Jane Temple. She sits in her high chair listening as her screen parents and another couple chat about having seen The Front Page; then she flops over in sleep and dreams a ten-minute version of the story featuring her and her tiny playmates.

Like the other kids in the Baby Burlesks, Shirley was under exclusive contract to producer Jack Hays. To finance his share of the shorts (Educational supplied 75 percent of the funding, Hays 25 percent), Hays farmed the kids out for modeling gigs, promotional gimmicks, bit parts or walk-ons, anything that required a child, pocketing most of the money and passing a pittance along to the parents (in Shirley’s case the few dollars supplemented her father George’s income as a branch manager for California Bank). All that shuttling around L.A. on Hays’s loan-outs, on top of her lessons at Mrs. Meglin’s Dance Studio, gave Shirley a tidy fund of experience for one so young.

After Runt Page the dubbing by adult voices was abandoned, and for the rest of the Baby Burlesks’ brief run the kids would all perform, for better or worse, with their own voices. In Shirley’s case it was for the better, as it turned out she could sing and dance. Here, in her seventh Baby Burlesk, Glad Rags to Riches, she sings for the first time on screen, playing Nell (aka night club chanteuse La Belle Diaperene). The song is “She’s Only a Bird in a Gilded Cage”; Shirley is four years and nine months old.

In September 1933 Jack Hays declared personal bankruptcy, and George Temple used his banking contacts to negotiate with Hays’s court-appointed trustee to buy back Shirley’s contract for $25. (Hays, one of Hollywood’s true bottom-feeders, said nothing at the time. But later, after Shirley had hit it big, he tried suing for half a million dollars, claiming the sale had been illegal. His nuisance suit dragged on for years before he finally settled for $3,500.)

After two-and-a-half years, in which she made 15 shorts and appeared in five features, Shirley was unemployed. Then, as the saying goes, fate intervened. At the end of November 1933, at a sneak preview for What’s to Do?, one of the Educational shorts Shirley had made on loan from Hays, she and her mother met songwriter Jay Gorney, recently hired by Fox Film Corp. This landed her an audition with Gorney and his partner Lew Brown, who was also serving as associate producer under Fox production chief Winfield Sheehan. Brown and Gorney cast her in a small part in a picture that was already well into production. For all intents and purposes, whatever her previous experience, Shirley Temple’s screen career — and certainly the Shirley Temple Phenomenon — began with…

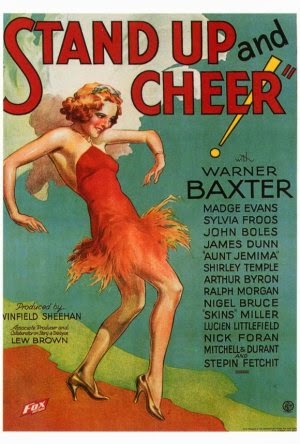

Stand Up and Cheer!

(released April 19, 1934)

Stand Up and Cheer! was an “all-star” revue masquerading as a standard book musical (the original working title was Fox Follies). The premise of Ralph Spence’s script, based on a “story idea suggested by” Will Rogers and Philip Klein, was that the U.S. President, in order to help people forget their troubles during the Depression, creates a new cabinet post, Secretary of Amusement, and appoints Broadway producer Lawrence Cromwell (Warner Baxter, essentially xeroxing his Julian Marsh from 42nd Street the year before) to oversee federally-funded public entertainment.

This provided the framework for a series of songs and specialty numbers by guest artists. Most of them were second- and third-string stars even at the time — vaudevillian Sylvia Froos, dreamboat tenor John Boles, blackface red-hot-mama entertainer Tess “Aunt Jemima” Gardella, hillbilly singer “Skins” Miller, knockabout comics Mitchell & Durant — and they’re all now generally (even utterly) forgotten. In fact, the one who’s best-remembered today is the one who wasn’t a star at all — yet: Shirley herself. In this poster she receives seventh billing, but on screen she’s billed third, right after romantic ingenue Madge Evans. Clearly, Fox had some inkling of what they had on their hands.

In Child Star Shirley remembers her mother taking her on December 7, 1933 to audition for Jay Gorney and Lew Brown. She sang “Lazybones” sitting on Brown’s piano, then slid down and stood by while the two songwriters discussed her as if she weren’t there (none of them suspecting, no doubt, that she’d be writing about it half a century hence). Brown was dubious; Winfield Sheehan, he said, was “high on the other kid.” Gorney demurred: “Unnatural, precocious. A revolting little monster.” Brown agreed, and they offered Shirley the part. After all, they wrote the songs for Stand Up and Cheer!, plus Brown was the picture’s associate producer. Shirley never knew how they brought Sheehan around, but Abel Green, in reviewing the picture for Variety, mentions approvingly that Brown had “held out…for that cute Shirley Temple.”

Shirley’s share of Stand Up and Cheer! consisted of two brief scenes, a curtain-call appearance in the movie’s finale, and a song-and-dance duet with James Dunn to “Baby, Take a Bow”. It may have helped them both that “Baby, Take a Bow” was the best song in the score. Or was it that it just seemed like the best because Dunn and Shirley performed it? That’s a chicken-or-the-egg question, but the bottom line was beyond debate: “Baby, Take a Bow” was the highlight of the weird, unruly hodgepodge that was Stand Up and Cheer!

The picture was deep into shooting when Shirley was cast, and the cash-strapped studio couldn’t afford to dawdle, so she had some serious catching up to do. To save rehearsal time, dance director Sammy Lee jettisoned the tap routine he’d taught to Dunn and had the actor learn the steps Shirley already knew from Mrs. Meglin’s. Then, late on her first morning, it was off to the sound studio to pre-record the song. Dunn flubbed several takes, then finally got it right. When her turn came, Shirley stood on a stool (her mother had taught her the words to the song just minutes before) and sang — then was mortified when, on the very last note, her voice slipped into an unintended falsetto (“Dad-dee, take a bow-oo!”). She thought she’d ruined the take and was terrified she’d be fired, but she needn’t have worried; that little half-yodel at the tail end of her vocal provided the perfect “button” to the song and firmly cemented her Cute Quotient.

Stand Up and Cheer! ran 80 minutes, and Shirley was on screen for a mere 5 minutes, 5 seconds. (The picture survives only in a 69 min. version reissued after Fox had merged with Darryl Zanuck’s 20th Century Pictures — but considering that by that time Shirley was the main selling point, it’s a cinch they didn’t cut a frame of hers.) Fleeting as they were, those five minutes were all she needed, and there was no doubt who stopped the show. Variety’s Green got right to the point. In his very first sentence, he wrote: “If nothing else, ‘Stand Up and Cheer’ should be very worthwhile for Fox because of that sure-fire, potential kidlet star in four-year-old Shirley Temple.” (Shirley was five — in fact, she turned six the day before Green’s review appeared — but never mind; Fox publicity had already shaved a year off her age.)

Meanwhile, over on the other coast, the New York Times’s Mordaunt Hall was borderline obtuse. He absurdly compared Stand Up and Cheer! to Gilbert and Sullivan and spent long inches recounting the picture’s plot — not its most prominent virtue — and praising an excruciating scene between Stepin Fetchit (so popular in the ’30s, so cringe-making today) and a penguin in a coat and hat claiming to be Jimmy Durante (the voice impersonated by Lew Brown). But even Hall paused to mention “a delightful child named Shirley Temple.”

Even before the public verdict was in, Winfield Sheehan knew what he had, and he wasted no time locking Shirley down. Two weeks after Shirley’s audition for Brown and Gorney, he tore up the old one-picture, two-week contract and offered a new one for a year, with an option to renew for seven. The money was a lot better, but Shirley and her parents were still dealing in a buyer’s market, and Fox got a sweet deal.

That was the easy part. Now the question was: How could Fox — bleeding cash, defaulting on loans and teetering on bankruptcy — exploit their most promising new star when she was only five — oops! make that [wink] four — years old? While they mulled that over, Fox decided to make a little mad money by loaning her out. And so it was that Shirley Temple’s first above-the-title credit, and the role that confirmed her as a bona fide star, came to her from another studio.

To be continued…

Shirley Temple Revisited, Part 2

Even at the age of five, Shirley already knew two things: (1) animals can’t be counted on to follow the script, and you have to be ready to deal with what they actually do; and (2) no matter what happens, only the director gets to call “Cut!” (By the way, the pony’s kick did not remain in the picture; it would have detracted too much from the “murder” of the doll, the dramatic point of the scene.)

Shirley’s new contract with Fox was exclusive, but in the immediate aftermath of shooting “Baby, Take a Bow” for Stand Up and Cheer! all the studio found for her to do was a less-than-worthless bit in a Janet Gaynor/Charles Farrell romance called Change of Heart. Eight seconds on screen — with her back to the camera, yet! — and not a syllable of dialogue; it was worse than the bits Jack Hays used to send her on. Mother Gertrude set out to drum up some work — if some other studio wanted her daughter, surely a loan could be worked out — and she had just the picture in mind, over at Paramount. It was one for which Shirley had already auditioned and been dismissed out of hand. (“They took one look, watched me dance, and rejected me without a smile.”)

Little Miss Marker

(released June 1, 1934)

Somehow, this time Gertrude was able to wangle an interview with the movie’s director, Alexander Hall. In Child Star Shirley doesn’t know how Mother did it; I wouldn’t be surprised if word of Shirley’s song-and-dance with James Dunn was already circulating on the Hollywood grapevine. In any event, Shirley auditioned for Hall personally.

Somehow, this time Gertrude was able to wangle an interview with the movie’s director, Alexander Hall. In Child Star Shirley doesn’t know how Mother did it; I wouldn’t be surprised if word of Shirley’s song-and-dance with James Dunn was already circulating on the Hollywood grapevine. In any event, Shirley auditioned for Hall personally.“No, kid! Stop! We’re finished.” It was as simple as that; Shirley had the part. Paramount offered Fox $1,000 a week for Shirley’s services (a huge profit over the $175 in her Fox contract), and on March 1, 1934 Shirley reported for her first costume fittings for Little Miss Marker.

William R. Lipman, Sam Hellman and Gladys Lehman’s script was adapted from a story by Damon Runyon about a sourpuss bookie named Sorrowful who grudgingly accepts a bettor’s small daughter as a sort of “hostage” for a two-dollar bet on a horse race. The father promises to get the money and be right back, but he never comes back. Sorrowful finds himself saddled with the little girl, whose sunny sweetness gradually thaws his heart, brightens his outlook and loosens his airtight purse strings. Everyone notices the change the tot makes in Sorrowful, and they warm to little “Marky” themselves.

Damon Runyon died in 1946, but his name has stayed current in American culture thanks to the Broadway musical Guys and Dolls (its title taken from one of his story anthologies, its plot from two of his tales). But Guys and Dolls has also skewed the popular image of his stories and what it means to be “Runyonesque”. The musical is set in a rollicking fantasy land of cute underworld denizens — grifters, mugs, oafs and dames, colorful and essentially harmless. In Runyon’s stories there is humor, to be sure, but it’s not rollicking; it’s more often sardonic, even mordant, and the atmosphere of the stories, despite the picturesque speech, is hardly fantasy. The world of Runyon’s nameless narrator is gritty and down to earth, lit by bare bulbs in cheap hotel rooms and the gaudy glare of street neon; we can almost smell the cheap cigars and stale perfume. Things may work out — for the time being — for the characters, but it’s usually thanks to ironic accidents, not a benign universe. There’s often an undercurrent of menace beneath the whimsy, and bad things do happen.

And so it is in “Little Miss Marker”. One snowy night Marky wakes to find her nursemaid asleep and Sorrowful gone. Running outside barefoot in her nightgown, she tracks him to the Hot Box nightclub and runs into his arms just as a killer named Milk Ear Willie is about to settle an old grudge by plugging Sorrowful. Willie changes his mind, so Marky has saved Sorrowful’s life — but at the cost of her own. She contracts pneumonia and dies in hospital, despite the efforts of Sorrowful and his associates (even Milk Ear Willie chips in, kidnapping a famous child specialist to attend Marky’s bedside). Minutes after Marky’s death her father turns up, having suffered from amnesia since the day he left his little girl with the bookmaker. He has read about Marky in the newspapers and has finally come to take her home. “I suppose I owe you something?” he asks Sorrowful. Yes, says the bookie, you owe me two bucks. “I will trouble you to send it to me at once, so I can wipe you off my books.” He is once again the old Sorrowful, with the same “sad, mean-looking kisser” he had before — “and furthermore,” says the narrator, “it is never again anything else.”

The movie keeps Runyon’s hospital climax — Marky is there with life-threatening injuries from falling from a horse, not pneumonia — but softens the ending: Marky lives, and Sorrowful’s reformation is allowed to stick. (The writers also gave Sorrowful a surname, Jones, which is not in the story but has stayed with him through two remakes.) Otherwise, it’s faithful to the spirit of Runyon’s story — basically a drama with small comic flourishes — with a suitable mix of seediness and vulgar glamour. Surely, Runyon was pleased.

Little Miss Marker contains one of the most unusual movie pairings of the 1930s: Shirley Temple and Adolphe Menjou. The usually dapper, immaculately tailored Menjou (he was voted Best Dressed Man in America nine times) was, at first glance, an odd choice not only to team with a child but to portray the rumpled, unkempt Sorrowful Jones. But it works; Shirley’s Marky brings out the debonair sport in Menjou’s Sorrowful, the one we knew was there all the time, by inspiring him to move to a more suitable apartment and upgrade his wardrobe. (Curiously enough, Menjou would play a similarly disheveled grump, and have a similar rapport with kids, in his last picture, Disney’s Pollyanna in 1960 — this time with two child stars, Hayley Mills and Kevin Corcoran.)

Shirley says in Child Star that Menjou once offered to play hide-and-seek with her, but otherwise tended to keep his distance (“off-camera he treated me with the reticence adults commonly reserve for children”). But when the camera’s rolling the two have a remarkable chemistry. It’s there when Marky and Sorrowful first meet, as she stands beside her father on the divider railing in Sorrowful’s shabby office. Sorrowful orders Marky “down offa there”, but she teases him: “Look, Daddy, he’s running away! Is he afraid?…You’re afraid of my daddy! Or you’re afraid of me. You’re afraid of something…” There follows a remarkable moment when Sorrowful picks Marky up, supposedly to get her off the railing, but holds her for a short while, her hands resting on his shoulders, while their eyes meet. Then he sets her down and growls to his henchman Regret (Lynn Overman), “Take his marker…A little doll like that’s worth twenty bucks. Any way you look at it.” (“Yeah,” Regret grumbles, “she oughta melt down for that much.”)

The chemistry is there, too, in a charming scene where Sorrowful and Marky talk about God, and he grudgingly agrees to teach her to say her prayers: “All right, get outta bed. I’ll show you how to pray. Sort of. But don’t you tell anybody, see?” The topper to the scene is the look on Sorrowful’s face when he hears why she wanted to learn: “And please, God, buy Sir Sorry a new suit of clothes.” In the very next scene, Sorrowful the sartorial butterfly has hatched out of his rumpled cocoon. (“Sir Sorry the Sad Knight” is the name Marky gives Sorrowful; she names all his cronies according to the stories she’s heard about King Arthur.)

Little Miss Marker fleshed out and in many ways improved Runyon’s original story. The amnesiac-father angle was always a bit of a credulity stretch; in the movie he becomes a suicide — driven off the end of his rope when the bet he placed with Sorrowful turns out a loser. This heightens Sorrowful’s sense of obligation to Marky: the race was rigged and he knew it when he took the man’s bet. It also links Marky to that losing horse, the ironically named Dream Prince. When Big Steve, Dream Prince’s owner, is suspended over suspicions about that fixed race, Steve and Sorrowful set Marky up as Dream Prince’s dummy owner so the horse can continue to run. Marky’s affection for “the Charger” (another one of her fanciful King Arthur names) draws her, Sorrowful and Bangles closer together, and leads to a crisis when Big Steve gets wind of shenanigans behind his back.

Little Miss Marker fleshed out and in many ways improved Runyon’s original story. The amnesiac-father angle was always a bit of a credulity stretch; in the movie he becomes a suicide — driven off the end of his rope when the bet he placed with Sorrowful turns out a loser. This heightens Sorrowful’s sense of obligation to Marky: the race was rigged and he knew it when he took the man’s bet. It also links Marky to that losing horse, the ironically named Dream Prince. When Big Steve, Dream Prince’s owner, is suspended over suspicions about that fixed race, Steve and Sorrowful set Marky up as Dream Prince’s dummy owner so the horse can continue to run. Marky’s affection for “the Charger” (another one of her fanciful King Arthur names) draws her, Sorrowful and Bangles closer together, and leads to a crisis when Big Steve gets wind of shenanigans behind his back.

To be continued…

Shirley Temple Revisited, Part 3

At this point in our story it’s still the spring of 1934. Before renting Shirley Temple out to Paramount to become a star, Fox frittered her away in one more pointless bit in Now I’ll Tell. Actually, the picture’s full title on screen was “Now I’ll Tell” by Mrs. Arnold Rothstein, and as that suggests, it purported to be the inside dope on the high-flying life and mysterious death of Mrs. Rothstein’s deceased husband, the gangster/gambler who fixed the 1919 World Series, was shot in November 1928 (apparently for welshing on a poker debt), and died two days later refusing to name his killer. Names were changed to protect the guilty, so Spencer Tracy starred as “Murray Golden”, with Helen Twelvetrees as his saintly, noble wife (Mrs. Rothstein wrote the story, remember!), and with Rothstein’s many mistresses combined into one person and played by 18-year-old Alice Faye.

Shirley’s role was an inch or two better than in Change of Heart: 42 seconds on screen and a whopping five lines of dialogue (to wit: “And we saw a cow there, too!”, “Does a black cow make black milk?”, “Good night”, and “Good night, Daddy” — twice). Publicity poses like this one may have led Shirley to misremember her role as that of Tracy’s daughter; in fact, she played the daughter of Tommy Doran (Henry O’Neill), a boyhood chum of Golden’s who grows up to be a police detective — on the other side of the law from his old pal. A decent enough gangland melodrama, Now I’ll Tell hit screens one week after Little Miss Marker, and could only have underscored Fox’s cluelessness.

(A side note: While Fox quickly learned to value Shirley, they never did know what they had in Spencer Tracy. They put him in 18 pictures in five years, usually as mugs and lummoxes, with the occasional loan-out here and there. Gradually he built a reputation as one of the best actors in town, but Fox kept wasting him on parts you could practically train a gorilla to play. Eventually they let him slip through their fingers into a contract with MGM in 1935. Within two years at Metro, Spence had snagged his first Oscar nomination; in the following two years he got his second and third, winning both times.)

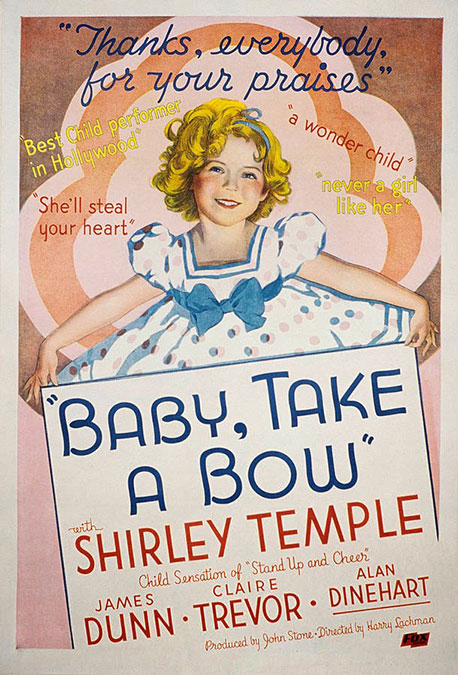

After Now I’ll Tell, however, Shirley’s days of Poverty Row shorts, four-line bits and uncredited walk-ons were finally behind her. For her next picture, she got top billing at last from her home studio, and just to remind audiences where they’d seen this kid before, Fox changed the title to…

Baby Take a Bow

(released June 30, 1934)

First, an explanation of a trivial point, just so you don’t suspect sloppy copy editing here at Cinedrome. The title of Jay Gorney and Lew Brown’s song “Baby, Take a Bow” has a comma, and the comma appears in this and some other posters, ads and lobby cards for the movie. But it’s not on the picture’s main title card as it appears on screen. Therefore, I’ll be using the comma when referring to the song, but not using it when I’m referring to the movie. Got it?

First, an explanation of a trivial point, just so you don’t suspect sloppy copy editing here at Cinedrome. The title of Jay Gorney and Lew Brown’s song “Baby, Take a Bow” has a comma, and the comma appears in this and some other posters, ads and lobby cards for the movie. But it’s not on the picture’s main title card as it appears on screen. Therefore, I’ll be using the comma when referring to the song, but not using it when I’m referring to the movie. Got it?Robert Armstrong and John Mack Brown played two ex-cons trying to go straight who fall under suspicion when a crony from their criminal days steals a pearl necklace from their wealthy employer. The thief tries to get the two to fence the pearls but they refuse. Complications arise when the thief, sensing the cops hot on his trail, stashes the necklace with Armstrong’s unsuspecting little girl, who thinks it’s a birthday present. What follows is a comic round of button-button-who’s-got-the-button as the thief tries to retrieve the pearls; the heroes try to return them to their boss; an implacable insurance detective seeks to get the goods on the heroes, whom he suspects of the theft; and the little girl thinks it’s all a game of hide-and-seek.

Be that as it may, we certainly know who played the kid in the sound remake. Shirley is shown here with Claire Trevor, who plays her mother and James Dunn’s wife. Trevor is younger and softer in Baby Take a Bow than we remember her from her better-known performances — Stagecoach; Key Largo; The High and the Mighty; Murder, My Sweet — she could almost pass for Ginger Rogers here.

Baby Take a Bow opens as Eddie Ellison (Dunn) is released from Sing Sing, promising to go straight. His girl Kay (Trevor) meets him at the gate, with continuing tickets for them to Niagra Falls for a justice of the peace wedding and honeymoon. At the same time we meet insurance investigator Welch (Alan Dinehart in an interesting performance), a tinhorn Javert who bluffly pals around with the men of various police forces — and tries in vain to make time with Kay. Everybody, especially Kay, makes it clear that they don’t like him, but Welch remains oblivious, blithely carrying on as if he’s one of the guys. Six years later, when Eddie and Kay have built a happy home with their daughter Shirley (star and character share the given name), it will be Welch who tries to hound Eddie and his pal Larry (Ray Walker) back into prison.

Variety’s reviewer “Kauf” pegged Baby Take a Bow exactly: “Without Shirley Temple this might have been a pretty obvious and silly melodrama, but it has Shirley Temple so it can go down on the books as a neat and sure b.o. (box office) hit, especially for the family trade.” (It’s a pity Mori couldn’t have reviewed it; it would be interesting to have him compare it to Square Crooks — assuming he even remembered a six-year-old silent B picture as late as 1934.) Meanwhile, back east at the New York Times, the anonymous reviewer sounded the first notes of praise mixed with highbrow condescension that would increase in some quarters in coming years (and would lead eventually to a successful libel suit against novelist Graham Greene and the British magazine Night and Day):

Little Shirley Temple continues in her new film at the Roxy to be the nation’s best-liked babykins. A miracle of spontaneity, Shirley successfully conceals the illusion of sideline coaching which, in the ordinary child genius, produces homicidal impulses in those old fussbudgets who lack the proper admiration for cute kiddies.

Before embarking on her next picture at Fox, Shirley was shuttled back to Paramount for another loan-out:

Now and Forever

(released August 31, 1934)

Shirley’s billing on Now and Forever was again above the title, but third this time. Still, when you’re billed third after Gary Cooper and Carole Lombard, you’ve really got no kick coming. (On screen she gets an “and”: “And SHIRLEY TEMPLE”.) Even more significantly, the music under the opening titles is an instrumental rendition of “Laugh, You Son of a Gun” — reminding audiences of Little Miss Marker the way Baby Take a Bow had reminded them of Stand Up and Cheer!

To be continued…

Shirley Temple Revisited, Part 4

According to the IMDb, Now and Forever‘s U.S. release date was August 31, 1934. However, it wasn’t reviewed by the New York Times or Variety until October 13 and 16, respectively. Apparently, either Fox sent the picture off to down-market engagements two-and-a-half months before opening it in New York — or (more likely, I think) the IMDb has the date wrong.

Whatever the case, both Andre Sennwald in the Times and Abel Green (again) in Variety pegged Shirley as Now and Forever‘s saving grace. Sennwald:

The little girl has lost none of her obvious delight in her work during her rise to fame. In “Now and Forever” she is, if possible, even more devastating in her unspoiled freshness of manner than she has been in the past…With Shirley’s assistance [the photoplay] becomes, despite its violent assaults upon the spectator’s credulity, a pleasant enough entertainment.

And Green:

“Now and Forever” is a remote title; it strains credulity; it can’t stand analysis; it has sundry other technical and plausibility shortcomings — but it has Shirley Temple and that virtually underwrites it for boxoffice…Shirley Temple in “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” would probably click just as well.

In these reviews, both written by seasoned showbiz observers, the subtext is unmistakeable: Shirley Temple saves the show; Gary Cooper and Carole Lombard do their best, but without Shirley they’d have gone down with the ship. And Shirley is still only six years old.

Next it was back home to Fox for…

Bright Eyes

(released December 20, 1934)

As bad as the Smythes are, they’re not the worst of it. That would be their daughter Joy (Jane Withers), a screaming little monster in a perpetual state of tantrum, and the most misnamed child in the history of human life on Earth.

As bad as the Smythes are, they’re not the worst of it. That would be their daughter Joy (Jane Withers), a screaming little monster in a perpetual state of tantrum, and the most misnamed child in the history of human life on Earth.

In real life, eight-year-old Jane was nothing like the character she played. Bright Eyes was her big break after a handful of uncredited bits since 1932. Fox quickly signed her to a seven-year contract and she went on to become a star in her own right, though inevitably in Shirley’s shadow, especially since they worked for the same studio. The two girls never worked together again — which is a pity, because Jane was the perfect foil for her younger co-star, and in Bright Eyes she comes as close as anybody ever did to stealing a show from Shirley Temple. Playing an obnoxious, spoiled-rotten brat, Jane was genuinely funny — no small achievement when you consider how many child actors over the years have tried to be funny, only to come off looking like obnoxious, spoiled-rotten brats.

Jane continued acting into her early 20s, even after 20th Century Fox dropped her in 1942, then she retired from the screen in favor of marriage to a rich Texas oil man. That foundered after eight years, and Jane made a comeback as a character actress in George Stevens’s Giant in 1956. Thereafter, she stayed busy in movies and on TV, and she became familiar to millions of baby boomers as Josephine the Plumber in a series of commercials for Comet Cleanser in the 1960s and ’70s. As of this writing Jane Withers is still with us, and hopefully in good health and spirits. Continued long life to her.

* * *

In a nutshell — and not counting five shorts and bit roles under her old contract to Jack Hays, or the two walk-ons in Change of Heart and Now I’ll Tell — Shirley Temple’s output for 1934 consisted of a breakthrough debut in Stand Up and Cheer!, a confirming star turn in Little Miss Marker, a placeholding appearance in Baby Take a Bow, credit for the save in Now and Forever, and a tailor-made vehicle in Bright Eyes. A great year for any rising star, and unprecedented for one who turned six midway through it.

In Child Star Shirley remembers that when Oscar nominations for 1934 were announced, “a vicious cat fight had erupted. My name was on the nomination list and odds-makers had me an almost certainty to win.” She goes on to assert that a storm of protest arose over the Academy’s failure to nominate either Myrna Loy for The Thin Man or Bette Davis for Of Human Bondage, and that as a result her own nomination was rescinded and voting rules changed to allow for write-ins. I’ve been unable to find this confirmed anywhere else, and I suspect Shirley’s memory was playing her false. She doesn’t say which picture she believed she had been nominated for (if they’d had supporting awards in ’34, she might have been a cinch to win for Little Miss Marker, but those categories were still two years in the future). Shirley is right, however, about the write-ins and the protest — though the storm was more on behalf of Davis than Loy (in the end, the award went to Claudette Colbert for It Happened One Night; Davis, even with the write-ins, came in third).

Be that as it may, there was no ignoring Shirley’s meteoric rise to the top tier of box-office stars, and the Academy Board of Governors conferred a new award, a miniature statuette “in grateful recognition of her outstanding contribution to screen entertainment during the year”. The emcee at that year’s awards was the prolific Kentucky humorist, author and columnist Irvin S. Cobb (shown here with Shirley), one of those writers whose fame more or less died when he did in 1944. Most of his 60-plus books and 300 short stories are out of print now, and he is probably best remembered for what he said that night. First: “There was one great towering figure in the cinema game, one artiste among artistes, one giant among the troupers, whose monumental, stupendous and elephantine work deserved special mention…Is Shirley Temple in the house?” Then, after Shirley joined him at the podium: “Listen, y’all ain’t old enough to know what this is all about. But honey, I want to tell you that when Santa Claus wrapped y’all up in a package and dropped you down Creation’s chimney, he brought the loveliest Christmas present that was ever given to the world.”

In Child Star, even 50-plus years on, Shirley’s disappointment still sounds tender to the touch (“If mine was really a commendable job done, why not a big Oscar like everyone else’s?”), but I think she overlooks the specialness of her special award (the only one given that year). The miniature Oscar that was created just for her would remain the standard recognition for outstanding juvenile performers for the next 26 years, and would be given 11 more times. The last went to Hayley Mills for Pollyanna in 1960; after that, beginning with nine-year-old Mary Badham for To Kill a Mockingbird in 1962, the kids would have to take their chances with the grownups (and some — Patty Duke, Tatum O’Neal, Anna Paquin — would even win). Of those dozen miniature-Oscar winners — who include Mickey Rooney, Deanna Durbin, Judy Garland, Margaret O’Brien and others — the little girl who inspired the creation of it was the youngest to receive it. In fact, she remains to this day the youngest person ever to win anything from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. I doubt if that record will ever be broken.

Shirley Temple Revisited, Part 5

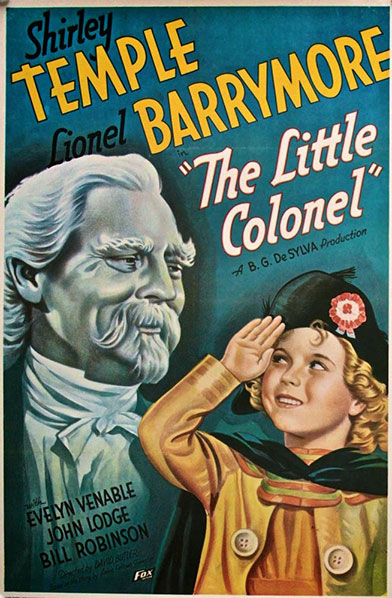

The Little Colonel

(released March 21, 1935)

Shirley’s first picture of 1935 was a period piece, her first costume drama as a star. The source material was a children’s book by Annie Fellows Johnston of McCutchanville, Indiana. Mrs. Johnston turned to writing at the age of 29 when her husband died in 1892, leaving her with three small stepchildren to raise on her own. The Little Colonel, published in 1895, was her third novel, and it proved so popular that she wrote a sequel a year until 1907. She wrote, in all, some four dozen books before she died in 1931 at age 68, but The Little Colonel was the only one that was ever filmed. It’s a pity Mrs. Johnston couldn’t have hung on for four more years and seen the apotheosis of her most famous creation.

Shirley’s first picture of 1935 was a period piece, her first costume drama as a star. The source material was a children’s book by Annie Fellows Johnston of McCutchanville, Indiana. Mrs. Johnston turned to writing at the age of 29 when her husband died in 1892, leaving her with three small stepchildren to raise on her own. The Little Colonel, published in 1895, was her third novel, and it proved so popular that she wrote a sequel a year until 1907. She wrote, in all, some four dozen books before she died in 1931 at age 68, but The Little Colonel was the only one that was ever filmed. It’s a pity Mrs. Johnston couldn’t have hung on for four more years and seen the apotheosis of her most famous creation.

Anyone who thinks that a movie is never as good as the book should try reading The Little Colonel. Mrs. Johnston’s ever-so-precious style hasn’t weathered the years well; I suspect it hadn’t by 1935, either. (It’s available online here if you want to check it out.) The story, as the saying goes, had “good bones”, and writer William Conselman fleshed them out rather better than Mrs. Johnston had. (Conselman also wrote Bright Eyes and would write for Shirley again.)

In Conselman’s script (unlike the original book), the story opens before the birth of its title character. A title tells us it’s “Kentucky in the ’70s”, and we meet old Colonel Lloyd (Lionel Barrymore), an unreconstructed Confederate for whom the War isn’t over. At a soiree at his plantation he offers a toast: “Gentlemen, I give you the South — and confusion to her enemies!” But it’s the Colonel who’s due for confusion; one of those “enemies”, a Northerner — named Sherman, no less — has won the heart of his beloved daughter Elizabeth (Evelyn Venable). The Colonel interrupts her and her intended (John Lodge) in the act of eloping, and he warns her: “Elizabeth, when that door closes, it’ll never open for you again.” Elizabeth leaves without another word, and she doesn’t close the door — she slams it.

Next scene, it’s six years later and the Shermans — Jack, Elizabeth and their daughter Lloyd (Shirley) — are at a military outpost on the edge of the western frontier. Lloyd has become the darling of the post, and she receives a commission as honorary colonel — an addition by Conselman that makes the girl a “little colonel” in fact, not just as the nickname the author gives her in the original story. The family has sold everything they own and left their Philadelphia home. Papa Jack is to continue west to make a new home for them; when he’s well-established and it’s safe, he’ll send for his wife and daughter. Until then, Elizabeth and the Little Colonel will return to Kentucky and live in a small cottage on the family property that was left to her by her mother.

Later, when the old man learns who she is, he is mollified, even apologetic. He may have disowned his daughter and her husband, but he sees no reason not to associate with his granddaughter — especially since she reminds him so much of himself (and his outcast daughter, though he won’t admit it).

There’s another teaming in The Little Colonel that also makes it crackle. Playing the Old Colonel’s butler Walker was Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. Robinson began in vaudeville in 1900, and by 1934, when The Little Colonel was made, he was universally recognized (and for that matter, still is) as one of the greatest tapdancers who ever lived. Shirley was always proud that she and Robinson were the first interracial dance team in movie history. More than that, because of the age difference between six-year-old Shirley and the 56-year-old Robinson (and at the time, let’s face it, because of the difference in the color of their skin), they were one male-and-female team whose dances carried no hint of courtship or romance — nothing but the sheer joy of dancing together. (“The smile on my face wasn’t acting,” Shirley said in Child Star; “I was ecstatic.”) The teaming was Winfield Sheehan’s idea, and he hesitated only because he was unsure if Robinson could act; his three previous screen appearances had been dance-only. Robinson passed a screen test, and that was that. In all, he and Shirley would make five pictures together (I’ll get to the others in their time), and it all started here.

Their first dance together was the famous staircase dance. It was Robinson’s signature act, and he modified it to accomodate Shirley’s abilities; she couldn’t have come up to his level in the rehearsal time they had — but then, probably nobody could, no matter how long they rehearsed. Shirley remembered her “Uncle Billy” as “a superlative teacher, imperturbable and kind, but demanding…Every one of my taps had to ring crisp and clear in the best cadence. Otherwise I had to do it over.”

It must be said that racial attitudes of the 1930s make The Little Colonel (and The Littlest Rebel, later in ’35) an awkward experience for some people today. It’s hard not to view these movies through the hindsight of how far African Americans have come (on screen and in real life) in the last 80 years. It’s worth remembering, though, the progress they had made by 1935 — what little there was, and only on screen at that — in the 40 years since The Little Colonel was written (or even the 20 years since The Birth of a Nation). We rightly cringe now when Colonel Lloyd calls to his granddaughter’s black playmates, “Come on, you pickaninnies!” But in Annie Fellows Johnston’s novel he uses an even uglier word — and for that matter, so does the Little Colonel herself. And to be fair to The Little Colonel (the movie), there’s a scene where Lloyd attends a black church’s baptism ceremony in a stream that runs through her grandfather’s property; the scene is presented unpatronizingly and without condescension. Also, the two most prominent black characters are played by Robinson as Walker and, as the Little Colonel’s cook and housekeeper “Mom Beck”, Hattie McDaniel (five years before she became the first African American to win an Academy Award). Both of them imbue their characters with a warmth and dignity that rises above the racism of the time.

Plus, of course and always, there’s the sheer pleasure of Shirley and Bojangles dancing.

Shirley Temple Revisited, Part 6

Our Little Girl

Our Little Girl

(released June 6, 1935)

I’m not going to spend a lot of time on Shirley’s next picture because…Well, if (as I said in Part 3) Now and Forever is a bit of a dud, Our Little Girl is a flat-out stinker. A country doctor (Joel McCrea) gets so wrapped up in his practice and his research that his wife (Rosemary Ames), feeling ignored, seeks comfort first in the company, then in the arms, of their bachelor neighbor (Lyle Talbot). Meanwhile, the doctor’s nurse (Erin O’Brien-Moore) nurses an unrequited love for him. Caught in the middle of all this, and neglected by both her parents, is the couple’s daughter (Shirley).

Shirley couldn’t save this one; nothing could. The script by Steven Avery and Allen Rivkin was an indigestible stew of sugar, soap and corn, and director John Robertson (a veteran whose credits went back to 1916) was utterly defeated by it. On the other hand, even a brilliant script couldn’t have survived Robertson’s leaden, clomping direction, which made the picture feel much longer than the 64 minutes it actually ran. Perhaps not incidentally, this was Robertson’s last movie, as it was for leading lady Rosemary Ames, whose two-year, eight-picture career ended here.

Shirley never made a worse movie, and neither did Joel McCrea. (Lyle Talbot did — but only because he made three pictures with Ed Wood.)

Variety’s reviewer “Odec” predicted (accurately) that “despite [the] story”, Shirley’s fans would make the picture profitable. At the New York Times, Andre Sennwald was less conciliatory: “As we have learned to expect, ‘Pollyanna’ and ‘The Bobsey Twins’ [sic] are classics of gutter realism by comparison with the sentimental syrups which Miss Temple’s impresarios arrange for the Baby Duse.“ Dyspeptic, yes, but Our Little Girl had it coming, and worse. (Mr. Sennwald still spoke fondly of Little Miss Marker, but he was clearly reaching a saturation point, if not with Shirley, at least with her vehicles. As fate would have it, he would review only two more of them — Curly Top and The Littlest Rebel, with increasing asperity — before dying in a gas-line explosion in his Manhattan penthouse on January 12, 1936; Sennwald was only 28.)

In Child Star, Shirley said of Our Little Girl, “I forgot it as soon as possible.” As well she might, but it wasn’t because of the picture itself; it was due to things that happened during shooting.

First: Shirley was going through the normal tooth losses of any kid her age, but shooting couldn’t be held up while they grew back, so she wore temporaries for the camera. One day on Our Little Girl‘s rural location, she sneezed two of hers out into a grassy meadow. The whole crew searched long through the grass, but to no avail, and the company had to wrap for the day while new ones were crafted for the little star. Shirley had conceived a girlish crush on Joel McCrea, and seeing his annoyance at the delay, she was accordingly chagrined.

But worse was to come; the very next day, Shirley’s chagrin turned to mortification. Standing with McCrea by a stream while lighting gaffers fiddled endlessly with their lights and reflectors, and with the long silence broken only by the trickle of the nearby brook, Shirley — there’s no gentle way to say it — wet her pants. Understandably, she immediately burst into tears. Mother Gertrude gently led her sobbing daughter to their trailer, where socks and undies were replaced, then Mother bucked up Shirley’s courage for the unavoidable return to the set. “Finally I mustered enough confidence to open the door,” Shirley wrote, “but only by convincing myself the whole thing had never happened.” She considered that moment her “Oscar performance”.

Poor Shirley. Even fifty-plus years on, writing in Child Star, her humiliation is still palpable. No wonder she forgot Our Little Girl without delay. We should too.

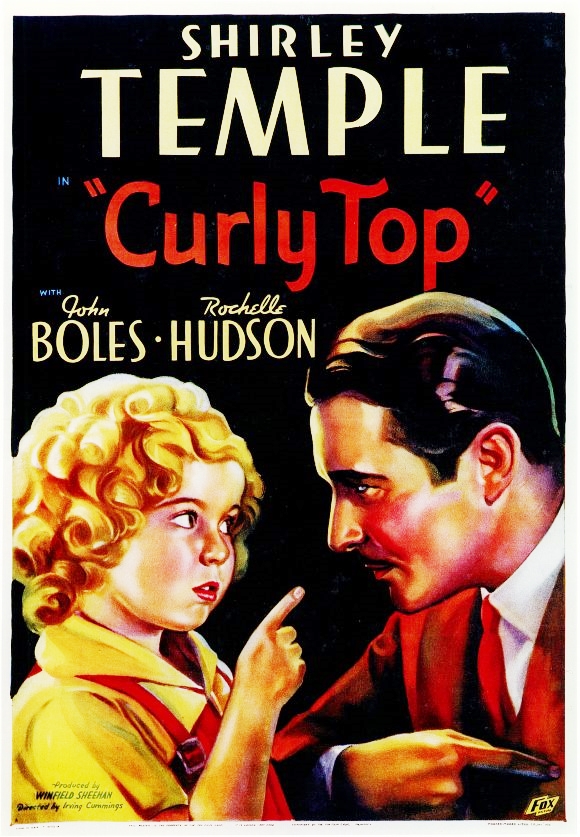

Curly Top

Curly Top

(released August 1, 1935)

Shirley plays Elizabeth “Curly” Blair, an orphan who charms Edward Morgan (John Boles), one of the rich trustees of the orphanage where she lives; Morgan legally adopts Curly while pretending to be acting on behalf of one “Hiram Jones.”

The story was a liberal reworking of Jean Webster’s 1912 novel Daddy Long Legs, which told of Judy Abbott, an orphan who, when she grows too old to stay at her orphanage, is sponsored through college by a benefactor who insists on remaining anonymous. By story’s end Judy learns that the mysterious “John Smith” is wealthy Jervis Pendleton, whom she knew (and had a girl’s crush on) from his visits to the orphanage. Now full-grown (and college educated), Judy marries him. Webster’s novel had already been filmed in 1919 with Mary Pickford and in 1931 with Janet Gaynor (and would be again in 1955, as a musical starring Fred Astaire and Leslie Caron). Since Fox had produced the 1931 version and still owned the screen rights to the story, they were at liberty to refashion it to fit Shirley.

Needless to say, if the boys at Fox couldn’t wait for Shirley’s adult teeth to grow in, they certainly couldn’t sit around while she reached an age to marry John Boles, so Patterson McNutt and Arthur Beckhard’s script supplied Curly with an older sister Mary (Rochelle Hudson) to be adopted with her and to discharge the romantic duties with the handsome Boles. Hudson and Boles even held up their end with the songs: Hudson, a neophyte singer, did quite well with “The Simple Things in Life” (by Edward Heyman and Ray Henderson), while Boles returned to his musical comedy roots with “It’s All So New to Me” (also by Heyman and Henderson) and the picture’s title song (Henderson and Ted Koehler).

But like the story, the supporting players (Boles; Hudson; Jane Darwell and Rafaela Ottiano as matrons at the orphanage; Esther Dale as Boles’s aunt; Billy Gilbert and Arthur Treacher as his cook and butler) were all beside the point. Shirley was just about the whole show. She is even the focus of both Boles’s songs. After singing “It’s All So New to Me”, while the orchestra wafts on in the background, he strolls around his palatial drawing room, where he fancies Shirley beaming down at him from the paintings on the walls…

But like the story, the supporting players (Boles; Hudson; Jane Darwell and Rafaela Ottiano as matrons at the orphanage; Esther Dale as Boles’s aunt; Billy Gilbert and Arthur Treacher as his cook and butler) were all beside the point. Shirley was just about the whole show. She is even the focus of both Boles’s songs. After singing “It’s All So New to Me”, while the orchestra wafts on in the background, he strolls around his palatial drawing room, where he fancies Shirley beaming down at him from the paintings on the walls…

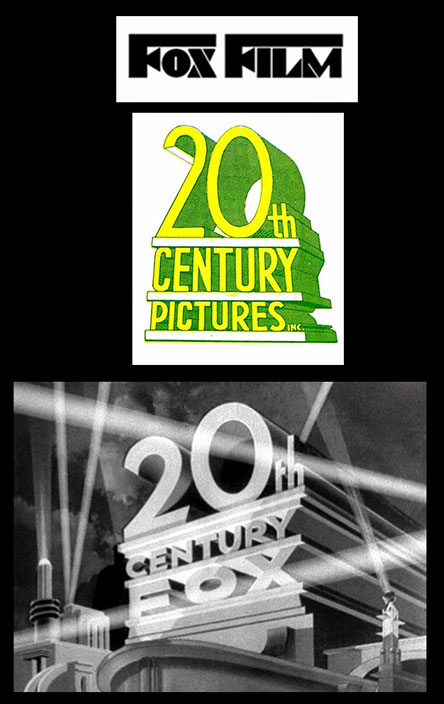

Curly Top was Shirley’s last picture for Fox Film Corp., and her last with Winfield Sheehan, who had piloted her career since Stand Up and Cheer! As chief of production in the wake of William Fox’s personal and professional nosedive in 1929-30, Sheehan had managed to stave off the studio’s total financial collapse (largely through hanging on to Will Rogers and locking Shirley into a long-term contract), but the waters were still rocky. Even before Curly Top went into production, there were rumors of negotiations with the upstart Twentieth Century Pictures, a thriving new kid in town, but one in need of a studio complex and distribution system — one like Fox’s, for example. On May 29, 1935, a merger was announced; the new studio would be called 20th Century Fox. Less than two months later, Winfield Sheehan was out as head of production, replaced by the man who had spearheaded Twentieth Century to a success that entitled it to be senior partner in its merger with the more venerable Fox. The man, moreover, who would be in charge of Shirley’s career for the rest of the 1930s: Darryl F. Zanuck.

To be continued…

Shirley Temple Revisited, Part 7

The creation of 20th Century Fox was announced as a merger, but it was really a friendly takeover. Darryl Zanuck (former production head at Warner Bros.) and Joseph Schenck (former president of United Artists) had formed 20th Century Pictures in 1933 as an independent concern, renting equipment and studio-and-office space from UA. In two years 20th Century had produced 18 pictures, all but one of which had made money, and several of which had made quite a lot: Folies Bergere de Paris, The House of Rothschild, The Affairs of Cellini, The Call of the Wild, Les Miserables, etc. But Zanuck got his hackles up when UA wouldn’t sell any of its stock to 20th Century, and he started looking around.

The creation of 20th Century Fox was announced as a merger, but it was really a friendly takeover. Darryl Zanuck (former production head at Warner Bros.) and Joseph Schenck (former president of United Artists) had formed 20th Century Pictures in 1933 as an independent concern, renting equipment and studio-and-office space from UA. In two years 20th Century had produced 18 pictures, all but one of which had made money, and several of which had made quite a lot: Folies Bergere de Paris, The House of Rothschild, The Affairs of Cellini, The Call of the Wild, Les Miserables, etc. But Zanuck got his hackles up when UA wouldn’t sell any of its stock to 20th Century, and he started looking around.

Enter Sidney Kent, president of Fox Film Corp. When Kent entered into merger negotiations with Zanuck and Schenck, he probably had visions of “Fox-20th Century Pictures”, thinking he was co-opting the rising competition and bringing a hot young producer into the Fox fold. But he didn’t figure on the drive and energy of Darryl F. Zanuck.

Neither did Winfield Sheehan. The Fox production chief knew there’d be room for only one chief at the new studio, and he braced himself for a struggle. But he was overmatched; Zanuck was younger, more aggressively ambitious — and, frankly, he had a better record at the box office. By the end of July 1935 Sheehan had taken a $420,000 buyout and left the company. Sidney Kent stayed on as president, at $180,000 a year, plus $25,000 as president of National Theatres Corp., Fox’s distribution affiliate. Just to show who 20th Century Fox’s real key figure was, Zanuck was made vice president in charge of production at $260,000 a year, plus ten percent of the gross on the pictures he supervised — plus enough stock in the company to ensure another $500,000 a year.

Such popularity did have its worrisome side, especially for Shirley’s parents; the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby was still news. Their concern would be borne out during a radio broadcast on Christmas Eve 1939, when a woman in the audience, unhinged by grief, pointed a gun at Shirley, determined to kill the body that she believed had stolen the soul of her own dead daughter; the danger passed when the woman was seized and disarmed by two FBI agents who had been alerted to her suspicious presence. But that’s getting ahead of my story. For now, in 1935, the studio engaged burly John Griffith to serve as Shirley’s chauffeur and bodyguard (Shirley considered him a grown-up playmate). “Watch the kid like a hawk,” Zanuck told Griffith. “If anything happens to her, this studio might as well close up.”

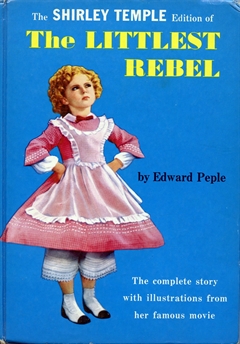

The Littlest Rebel

(released December 19, 1935)

Shirley’s first picture to bear the new 20th Century Fox logo (with its now-famous fanfare) had been in the works before the merger, as the cover of this sheet music suggests. The ostensible source was a play by Edward Peple that ran for 55 performances on Broadway in the winter of 1911-12 before embarking on a long and prosperous tour, making a child star of the ill-fated Mary Miles Minter. The play had been filmed before in 1914, a version now presumed lost. (Playwright Peple, like The Little Colonel author Annie Fellows Johnston, did not live to see Shirley’s remake, having died of a heart attack in 1924, age 54.)

Shirley’s first picture to bear the new 20th Century Fox logo (with its now-famous fanfare) had been in the works before the merger, as the cover of this sheet music suggests. The ostensible source was a play by Edward Peple that ran for 55 performances on Broadway in the winter of 1911-12 before embarking on a long and prosperous tour, making a child star of the ill-fated Mary Miles Minter. The play had been filmed before in 1914, a version now presumed lost. (Playwright Peple, like The Little Colonel author Annie Fellows Johnston, did not live to see Shirley’s remake, having died of a heart attack in 1924, age 54.)But actually, that’s a bit of an overstatement. In fact, several of the characters’ names survived from stage to screen. Shirley plays Virginia Cary, a six-year-old resident of her namesake state whose birthday party is interrupted by news of the firing on Fort Sumter. Her father (John Boles) soon rides off to war, leaving the plantation in the hands of his wife (Karen Morley), little Virgie, and their loyal slaves, led by butler Uncle Billy (Bill Robinson) and his assistant James Henry (Willie Best). Late in the war, the Union Army sweeps through, and Virgie’s defiance earns the amused respect of Yankee Col. Morrison (Jack Holt). When Capt. Cary sneaks home to attend his wife’s deathbed and is captured, a sympathetic Morrison tries to help him and Virgie escape through Union lines, but father and daughter are caught and the two men are condemned to the firing squad — Capt. Cary for spying, Col. Morrison for aiding and abetting the enemy. Virgie and Uncle Billy rush to Washington, hoping to obtain a pardon from President Lincoln. I won’t say how this all turns out, but even if I did it would hardly amount to a surprise or a spoiler.

The Littlest Rebel was aimed at duplicating the success of The Little Colonel; in fact, it surpassed it, and was one of Shirley’s smoothest pictures. The only thing that really dates it today — and it dates it terribly — is the racial attitude I mentioned in my notes on The Little Colonel. That attitude is even more glaring and uncomfortable in The Littlest Rebel because the picture deals directly with the Civil War itself. When Edward Peple wrote his play in 1914, the war was well within human memory; even by the time the movie was made, that generation had not yet passed away (three years later, in 1938, the 75th anniversary of the battle of Gettysburg would occasion a reunion of nearly 1,900 Civil War veterans). The Old South with its genteel planter aristocracy and loyal, happy, contented slaves was an article of faith in the Myth of the Lost Cause, one that died hard and bitterly, and it’s on full display in The Littlest Rebel. It’s difficult to argue with modern viewers who find it just too hard to take. (Shirley even plays one scene in blackface disguise, though at least we are spared the sorry spectacle of hearing her speak with a “darkie” accent.)

The Littlest Rebel was aimed at duplicating the success of The Little Colonel; in fact, it surpassed it, and was one of Shirley’s smoothest pictures. The only thing that really dates it today — and it dates it terribly — is the racial attitude I mentioned in my notes on The Little Colonel. That attitude is even more glaring and uncomfortable in The Littlest Rebel because the picture deals directly with the Civil War itself. When Edward Peple wrote his play in 1914, the war was well within human memory; even by the time the movie was made, that generation had not yet passed away (three years later, in 1938, the 75th anniversary of the battle of Gettysburg would occasion a reunion of nearly 1,900 Civil War veterans). The Old South with its genteel planter aristocracy and loyal, happy, contented slaves was an article of faith in the Myth of the Lost Cause, one that died hard and bitterly, and it’s on full display in The Littlest Rebel. It’s difficult to argue with modern viewers who find it just too hard to take. (Shirley even plays one scene in blackface disguise, though at least we are spared the sorry spectacle of hearing her speak with a “darkie” accent.)

So: The Littlest Rebel has Willie Best’s James Henry to neutralize (if not nullify) the humanity of Bill Robinson’s Uncle Billy — rather than complement and reinforce it, as Hattie McDaniel’s Mom Beck had done in The Little Colonel. Plus a slave population so happy in bondage that they have no interest in emancipation and don’t even understand what it is. With all that, it’s not surprising that many viewers prefer not to watch the picture today — much less show it to children who can’t place it in its proper historical context.

Variety’s reviewer “Land” pegged The Littlest Rebel exactly, noting its striking similarity to The Little Colonel, yet conceding that it probably “won’t dampen the enthusiasm of the Temple worshippers…All bitterness and cruelty has been rigorously cut out and the Civil War emerges as a misunderstanding among kindly gentlemen with eminently happy slaves and a cute little girl who sings and dances through the story…Story is synthetic throughout but smart showmanship instills the illusion of life.” In the New York Times, Andre Sennwald agreed: “You may have got the mistaken notion from ‘So Red the Rose’ [a Civil War melodrama released the month before] that the war between the States was filled with ruin, death, rebellious slaves and horrid Yankee barbarians. ‘The Littlest Rebel’ corrects that unhappy thought and presents the conflict as a decidely chummy little war…As Uncle Billy, the faithful family butler, Bill Robinson is excellent, and some of the best moments in ‘The Littlest Rebel’ are those in which he breaks into song and dance with Mistress Temple.”

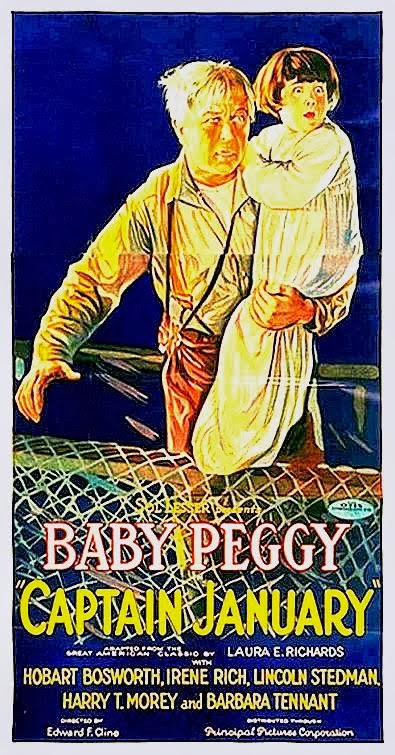

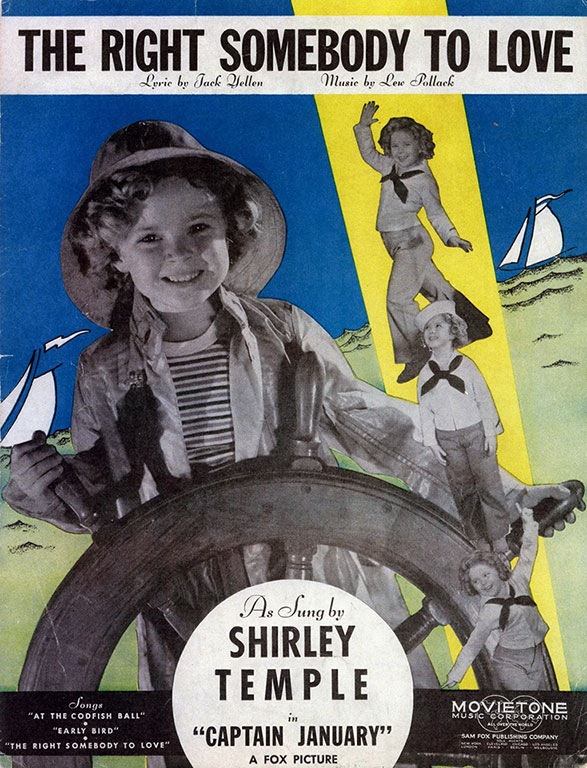

Captain January

(released April 24, 1936)

Captain January seems to have a special place in the hearts of Baby Boomers of a Certain Age, perhaps because it was one of Shirley Temple’s first features to go into television syndication in the 1950s. The source material was an 1891 novella by Laura E. Richards. Born Laura Elizabeth Howe in 1850, Mrs. Richards was the daughter of Julia Ward Howe, author of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”. A prolific author in her own right, Mrs. Richards wrote over 90 books, including, with her sister Maud Howe Elliott, a biography of their mother that won them a Pulitzer Prize in 1917. Mrs. Richards also wrote the children’s nonsense poem “Eletelephony” (“Once there was an elephant,/Who tried to use the telephant –/No! No! I mean an elephone,/Who tried to use the telephone…”). Unlike the authors of The Little Colonel and The Littlest Rebel, she lived long enough to see two movies made from her modest little story, dying in 1943 at 92. Whether she saw either movie, or what she thought of them, is not recorded.

Captain January seems to have a special place in the hearts of Baby Boomers of a Certain Age, perhaps because it was one of Shirley Temple’s first features to go into television syndication in the 1950s. The source material was an 1891 novella by Laura E. Richards. Born Laura Elizabeth Howe in 1850, Mrs. Richards was the daughter of Julia Ward Howe, author of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”. A prolific author in her own right, Mrs. Richards wrote over 90 books, including, with her sister Maud Howe Elliott, a biography of their mother that won them a Pulitzer Prize in 1917. Mrs. Richards also wrote the children’s nonsense poem “Eletelephony” (“Once there was an elephant,/Who tried to use the telephant –/No! No! I mean an elephone,/Who tried to use the telephone…”). Unlike the authors of The Little Colonel and The Littlest Rebel, she lived long enough to see two movies made from her modest little story, dying in 1943 at 92. Whether she saw either movie, or what she thought of them, is not recorded.

Mrs. Richards’s Captain January is a short-and-bittersweet tale of a retired old seafarer, one Januarius Judkins (“Captain January”), who lives alone tending a lighthouse on a small island off the rugged coast of Maine.

One night during a terrible storm he sees a ship founder in the rocky sea around his island. Venturing out in search of possible survivors, he finds only one, an infant girl clutched in her dead mother’s arms. He retrieves the child and several corpses, including both the baby’s parents. The anonymous dead he gives a decent burial on his island, the orphan girl he takes to shelter in his lighthouse. The next day a trunkfull of clothing belonging to the infant’s mother washes up on shore, but it contains no hint of the dead parents’ identities beyond some embroidered initials. With no way of knowing the baby’s name or family, he raises the girl himself, naming her Star Bright.

Ten years later, a woman on a passing cruise ship catches a glimpse of Star and is convinced she is the daughter of her dead sister, lost at sea with her husband and child while sailing home from Europe ten years earlier. It’s soon established beyond doubt that Star is Isabel Maynard, the long lost and presumed dead niece of that cruise ship passenger, Mrs. Morton. At first, Mrs. Morton wishes to take the girl to live with her, with full gratitude to Captain January for rescuing and raising her. But when she sees how it will break the hearts of both Star and the captain, she relents, and lovingly leaves the girl with the only father she’s ever known.

Even so, Captain January knows that his days on earth are nearly done, and he arranges with his friend, sailor Bob Peet, to keep an eye on the lighthouse whenever he sails by: If the little blue flag is flying, all is well; if the flag has been struck, it’s time for Bob to come and collect Star, and to take her to live with the Mortons, who will welcome her as one of their own — which in fact she is. Finally, in the spring of the following year, January feels his heart failing, and with his last ounce of strength he hauls down the little flag, then returns to his favorite chair to wait. “For Captain January’s last voyage is over, and he is already in the haven where he would be.”

Both Abel Green in Variety and Frank S. Nugent in the New York Times found Captain January to be “okay film fare” (Green) despite the “moss-covered script” (Nugent). One of the most interesting reviews came from across the Pond, where Graham Greene, writing in the London Spectator, found the picture to be “a little depraved, with an appeal interestingly decadent…Shirley Temple acts and dances with immense vigor and assurance, but some of her popularity seems to rest on a coquetry quite as mature as Miss [Claudette] Colbert’s, and on an oddly precocious body, as voluptuous in grey flannel trousers as Miss [Marlene] Dietrich’s.” Greene would pursue that line of thought in subsequent reviews, and would in time catch the gimlet eye of 20th Century Fox’s legal department. But I’ll get to that in its turn.

For the record, just in case you’ve lost track, Shirley was now seven years old; her eighth birthday was the day before Captain January opened in New York. Of course, hardly anybody besides her parents knew that; the rest of the world — including Shirley herself — thought she had just turned seven.

Next time: Fox’s top two female stars go head-to-head.

To be continued…

Shirley Temple Revisited, Part 8

Since I last posted on The Littlest Rebel I’ve had a chance to examine both Edward Peple’s play and novel of that title (both were copyrighted in 1911, so it’s impossible, without input from Mr. Peple’s heirs and descendants, to know whether the play was based on the novel or vice versa). It’s clear that Variety’s reviewer “Land” misspoke when he said there was “no trace” of Peple’s play in Edwin J. Burke’s script. In fact, Burke followed Peple’s broad outline quite faithfully, making such changes as the passage of 25 years and the talent on hand would call for. The stagebound bombast of the play’s dialogue is purged entirely, as is the “colored” humor that was hopelessly dated by 1935 (albeit replaced with humor that looks equally dated to us today). In the play, Virgie saves her father from the firing squad by appealing for clemency to Gen. U.S. Grant; having her appeal to President Lincoln in the movie was an obvious improvement. And, of course, song-and-dance opportunities were inserted for Shirley and Bill Robinson because it would have been plainly stupid not to do so.

“Land” was being either forgetful, ignorant or unjust. If he wanted to see a movie that really had no trace of its original source, he need only have waited for the picture that 20th Century Fox hustled Shirley into immediately after shooting wrapped on Captain January.

Poor Little Rich Girl

(released June 25, 1936)

Don’t be misled by the picture’s title as it appears on the cover of the sheet music below (and on several of the posters and lobby cards); the title was Poor Little Rich Girl, with no “The“. Poor Little Rich Girl has a distinction it shares with Our Little Girl: They are the only two pictures from Shirley’s reign as Fox’s box-office queen (before and after the merger) that are not available on DVD; both can be seen only on out-of-print colorized VHS tapes.

Don’t be misled by the picture’s title as it appears on the cover of the sheet music below (and on several of the posters and lobby cards); the title was Poor Little Rich Girl, with no “The“. Poor Little Rich Girl has a distinction it shares with Our Little Girl: They are the only two pictures from Shirley’s reign as Fox’s box-office queen (before and after the merger) that are not available on DVD; both can be seen only on out-of-print colorized VHS tapes.While waiting for the car to take them to the station, Barbara asks Collins what she’ll do while Barbara’s away at school.”I’m going to take a little vacation,” Collins tells her. Barbara asks what a vacation is. “It’s a rest, dear. It means getting away from people you’ve been with every day and seeing new faces. You really become another person on a vacation.”

The words leave a fateful impression on Barbara. When they get to the station, Collins stops to send a telegram telling the school that Barbara is on her way. That’s when she misses her purse; she must have dropped it as she got out of the car. She tells Barbara to wait, and rushes outside to search. There she’s run down by a car and winds up in the hospital, unconscious and unidentified.

Meanwhile, back in the station, Barbara gets tired of waiting and decides to take a “little vacation” of her own — and the “other person” she decides to become is Betsy Ware, an orphan in her favorite series of stories that Mrs. Woodward has been reading to her. In this guise she meets Jimmy Dolan and his wife Jerry (Jack Haley and Alice Faye), vaudevillians down on their luck and looking to break into radio. Taking little “Betsy” into their act, they rename her “Bonnie Dolan” and make the rounds as “Dolan, Dolan and Dolan” — and sure enough, before you can say “audition” they’ve landed starring spots on a radio show. On top of that, their show is sponsored by the Peck Soap Co., arch-competitor to Barry’s Beauty Soap, and little Barbara/Betsy/Bonnie has charmed the socks off cranky old Simon Peck (Claude Gillingwater), who had long vowed never to sponsor a radio program. All this happens within two days, while Barbara’s father, who assumes his daughter is safely ensconced at school in the Adirondacks, is romancing the Peck Soap Co.’s head of advertising (Gloria Stuart).

Well, all of this gets sorted out in time for a happy fadeout — that is, for everyone except poor Collins, the nursemaid, whom we last see comatose in the hospital while doctors puzzle over her identity, and who is never heard from again.

…and then, exactly the right touch: the dolls jump up and dance for her. The whole scene is a perfectly delightful expression of the loneliness of a friendless little girl, presented in song (by Shirley) and dance (by the dolls).

Other songs round out the musical program with variety and a satisfying range of styles. There are spoofs of commercial jingles in the ditties for the competing soap companies, “Buy a Bar of Barry’s” and “Wash Your Necks with a Cake of Peck’s”. A standard love song, “When I’m with You”, introduced by an unbilled Tony Martin at the very beginning of his career — and one year before his three-year marriage to Alice Faye. The song is then reprised by Barbara, singing to her father (and including the rather alarming line, “Marry me and let me be your wife.”). These and other songs, often heard in different forms in the background, on pianos, hand-organs and what-not, add to the varied musical texture of Poor Little Rich Girl.

Years later, Alice Faye shared her memories of Poor Little Rich Girl with her great fan W. Franklyn Moshier, author of the self-published The Films of Alice Faye (which was picked up by Stackpole Books in 1974 and published as The Alice Faye Movie Book), and Frank Moshier shared those memories with me when I knew him in the early ’70s. Evidently, Alice rankled at having to play second fiddle to this eight-year-old; according to Frank, she never talked about “Shirley”, it was always “that Temple child”. Alice told Frank, and Frank told me, stories of Shirley throwing tantrums on the set — red-faced, stomping, screaming “Miss Faye pushed me! Miss Faye pushed me!” Frank had the good sense not to include such tales in The Films of Alice Faye, but he did assert that “while pure and wholesome in appearance and the darling of everyone from Key West to Puget Sound, Shirley was more than a little difficult to work with.”

Nonsense. I didn’t believe these stories in 1972 and I don’t believe them now. They simply fly in the face of everything — everything — that everybody else who ever worked with Shirley had to say about her. We can only speculate on what prompted such melodramatic yarns; both Shirley and Alice — and for that matter, Frank Moshier — are beyond asking about it now. In any event, Alice Faye was not through playing second fiddle to Shirley Temple. Within a very few months, she’d be doing it again.

To be continued…

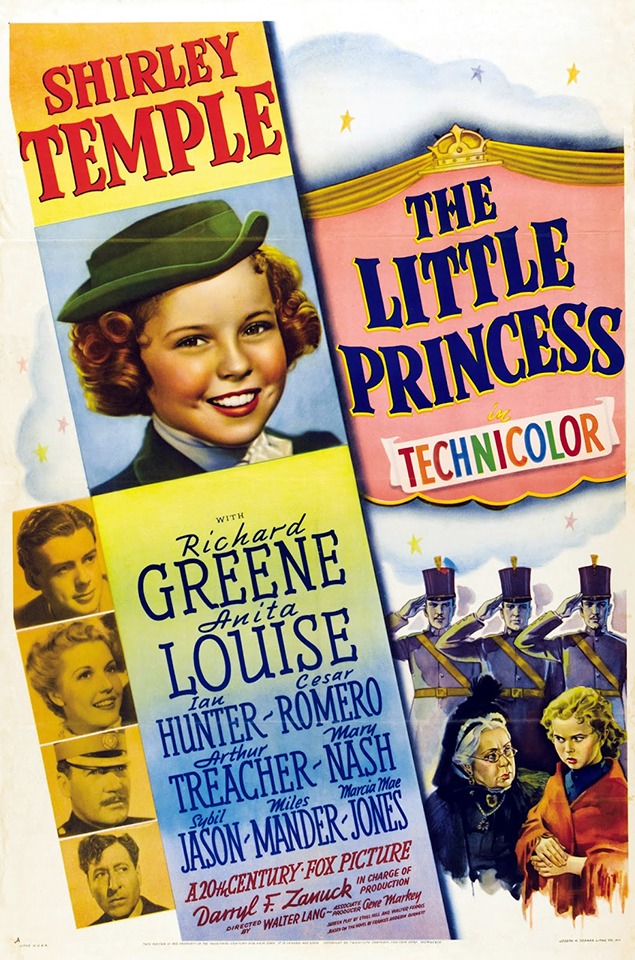

Shirley Temple Revisited, Part 9

During shooting on Poor Little Rich Girl, director Irving Cummings drew Shirley’s mother aside and warned her that (as Shirley recalled it in Child Star) “the studio would have to find better stories for me; I had lost that baby quality and was getting an emotional understanding, ‘like Helen Hayes when she started.'” Cummings’s point was well taken, but like contract players at other studios, Shirley was at the mercy of the 20th Century Fox front office, and their interest was in keeping her a baby as long as possible. Certainly that was how they played it for her next picture.

Dimples

(released October 11, 1936)

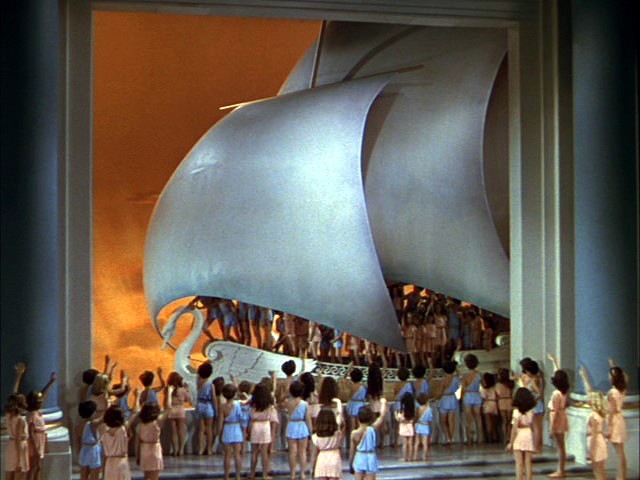

I’m going to pass over Dimples as quickly as duty will allow because, like Now and Forever, it’s a bit of a dud, and for similar reasons. The setting is New York in 1850; Shirley plays Chalvia Dolores Appleby, known by all as “Dimples”. As in Now and Forever, she’s the child of an unregenerate grifter, only this time it’s not her father but her grandfather, “Professor” Eustace Appleby (Frank Morgan). The Professor calls himself a music teacher of “the Pianoforte, the Bugle, the Melodion, the Drum, also Bird Calls”, but mainly he just stands in the crowd shilling while Dimples and his other “students” sing, dance and play their instruments in the streets. Then he starts the contributions when Dimples passes the hat and, while other bystanders are dropping coins in, he works the crowd picking pockets. In another similarity to Now and Forever, Dimples catches the eye of wealthy old Mrs. Drew (Helen Westley), who wants to lift her out of the Bowery poverty in which she lives with the Professor. At the same time, Mrs. Drew becomes estranged from her nephew Allen (Robert Kent) when he becomes romantically involved with (gasp!) an actress whom he decides to star in a production of Uncle Tom’s Cabin — in which he later hires Dimples to play Little Eva.

I’m going to pass over Dimples as quickly as duty will allow because, like Now and Forever, it’s a bit of a dud, and for similar reasons. The setting is New York in 1850; Shirley plays Chalvia Dolores Appleby, known by all as “Dimples”. As in Now and Forever, she’s the child of an unregenerate grifter, only this time it’s not her father but her grandfather, “Professor” Eustace Appleby (Frank Morgan). The Professor calls himself a music teacher of “the Pianoforte, the Bugle, the Melodion, the Drum, also Bird Calls”, but mainly he just stands in the crowd shilling while Dimples and his other “students” sing, dance and play their instruments in the streets. Then he starts the contributions when Dimples passes the hat and, while other bystanders are dropping coins in, he works the crowd picking pockets. In another similarity to Now and Forever, Dimples catches the eye of wealthy old Mrs. Drew (Helen Westley), who wants to lift her out of the Bowery poverty in which she lives with the Professor. At the same time, Mrs. Drew becomes estranged from her nephew Allen (Robert Kent) when he becomes romantically involved with (gasp!) an actress whom he decides to star in a production of Uncle Tom’s Cabin — in which he later hires Dimples to play Little Eva. In Child Star Shirley remembered Frank Morgan’s tireless efforts to upstage her and steal focus during their scenes — fiddling with his cuffs, flourishing his handkerchief, placing his stovepipe hat on a table between her and the camera so that she couldn’t be in the shot without stepping off her mark and out of the light. (“Both of us knew perfectly well what he was doing. There was no way I could cope, short of biting at his fingers.”) Director William A. Seiter was on to Morgan’s tricks too; in this scene, where Dimples sings “Picture Me Without You” (one of four pleasantly forgettable songs provided by Jimmy McHugh and Ted Koehler), Seiter made Morgan sit in a chair with his back to the camera. (“When this picture is over,” cracked producer Nunnally Johnson, “either Shirley will have acquired a taste for Scotch whiskey or Frank will come out with curls.”)