Nuts and Bolts of the Rollercoaster

At This Is Cinerama‘s premiere on September 30, 1952, historian Greg Kimble tells us, Lowell Thomas and Merian Cooper were as nervous as expectant fathers. But not Fred Waller; he sat quietly confident, and as the cheers and bravos echoed at the end, he allowed himself only the slightest of smiles. “I knew 16 years ago,” he said, “it would be like this.”

Even so, Waller never considered that night’s showing to be Cinerama in its final form; this was, in a sense, only the “third generation” version. Just as he had refined Vitarama’s 11 cameras and projectors down to five, and those five down to Cinerama’s three, he fully expected that the process would continue to evolve, and that he would be there to see it was done.

Truth be told, there was room for improvement, and Waller knew it.

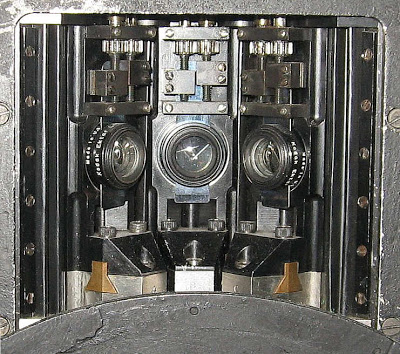

Some of Cinerama’s technical problems can be discerned in this frame (frames, actually) from Search for Paradise — although to be fair, by the time this picture was shot most of them had been considerably alleviated. Most often complained about were those dividing lines between the three panels. The panels overlapped by a degree or two, which meant that the overlap area would inevitably get the light from two projectors. To minimize this over-exposure, the sides of each projector’s film gate were supplied with little devices called (spellings vary) “gigolos”. These were serrated, comb-like assemblies mounted on cams that moved them up and down, once for each frame (i.e., 26 times per second) as the film passed through the gate. This was intended to cut down on the excess light hitting the overlap, and to blur the sharp division from one panel to the next. As a matter of fact, this worked reasonably well.

Some of Cinerama’s technical problems can be discerned in this frame (frames, actually) from Search for Paradise — although to be fair, by the time this picture was shot most of them had been considerably alleviated. Most often complained about were those dividing lines between the three panels. The panels overlapped by a degree or two, which meant that the overlap area would inevitably get the light from two projectors. To minimize this over-exposure, the sides of each projector’s film gate were supplied with little devices called (spellings vary) “gigolos”. These were serrated, comb-like assemblies mounted on cams that moved them up and down, once for each frame (i.e., 26 times per second) as the film passed through the gate. This was intended to cut down on the excess light hitting the overlap, and to blur the sharp division from one panel to the next. As a matter of fact, this worked reasonably well. Most noticeable of all was the parallax effect caused by the fact that the Cinerama camera was really three cameras, each with its own vanishing point. (“parallax [pár-a-laks] n. 1 the apparent difference in the position or direction of an object caused when the observer’s position is changed.”) Imagine yourself looking out at a vista: First you look straight ahead; then you take a step to your right and turn your head left; then two steps left and turn your head right. You’re looking at the same view each time, but from three ever-so-slightly different places. That’s parallax. Take this frame on the right, from the last scene of How the West Was Won, flying under the Golden Gate Bridge. The join lines and the difference in color textures from one panel to the next are glaringly obvious, but even more pronounced are the “elbows” in the bridge; everyone knows that the Golden Gate travels in a perfectly straght line between San Francisco on the left and Marin County on the right.

Most noticeable of all was the parallax effect caused by the fact that the Cinerama camera was really three cameras, each with its own vanishing point. (“parallax [pár-a-laks] n. 1 the apparent difference in the position or direction of an object caused when the observer’s position is changed.”) Imagine yourself looking out at a vista: First you look straight ahead; then you take a step to your right and turn your head left; then two steps left and turn your head right. You’re looking at the same view each time, but from three ever-so-slightly different places. That’s parallax. Take this frame on the right, from the last scene of How the West Was Won, flying under the Golden Gate Bridge. The join lines and the difference in color textures from one panel to the next are glaringly obvious, but even more pronounced are the “elbows” in the bridge; everyone knows that the Golden Gate travels in a perfectly straght line between San Francisco on the left and Marin County on the right.

Here’s a similar frame, on the left, from the same scene as it appears in a later DVD issue. The digital clean-up crew has been busy: Join lines have been digitally erased, the color has been made uniform, and the “elbows” have been smoothed out. But the digital wizards couldn’t do anything about how the three lenses saw the bridge. That’s how it was with the Cinerama camera. The parallax wasn’t always obvious — especially when you were careening up and down rollercoaster tracks or swooping over Niagara Falls or through Zion Canyon in Utah — but when it was, it was impossible to ignore.

As for the problem of slight variations in color, that was dependent on printing standards, which in most laboratories, as Hazard Reeves admitted, “have never been tight. If necessary,” he went on, “we’ll do our own printing.” But once again he ran up against the cheapskates at Stanley Warner. Not until 1958 did they agree to allot $200,000 for research into improved printing standards, and it wasn’t enough; Cinerama’s special in-house printers never materialized.

Jim, I agree with Ruth: with all the work you've put in on this fascinating, riveting series, I think it's well worth putting together and marketing a CINERAMA book. I say put together a synopsis and go for it! For that matter, I'd make make sure it had plenty of pictures, too! Now I'm off to read your next installment! 🙂

I just an online search for a book on Cinerama, and all I can find is a Lowell Thomas' paperback, "This is Cinerama". So, what do you suppose this means? It means that you are poised to write a book about Cinerama. You've already done the research; you just need to put in book format.