Say, What Ever Happened to Carman Barnes?

I can hear you now: “WHO???”

I can hear you now: “WHO???”

Frankly, that was exactly my reaction when I first encountered Carman Barnes’s name (and no, that’s not a typo: it’s “Carman”, not “Carmen”. Her great-grandmother was married three times, the last time to a man named Carman. Carman’s parents liked the sound of that, and there you are).

I was combing through some old fan magazines researching a post on Clara Bow’s talking picture career (that post, by the way, is still simmering on a back burner, refusing to come to a boil). In the May 1931 issue of Screenland Magazine I found an article by Sydney Valentine, “Danger Ahead for Clara Bow” (“She’s always taking chances! And now — what’s to become of her?”). Valentine offered unctuous advice to Clara on her floundering career and scandalous private life (one having largely caused the other), and he warned her:

Right now, out in Hollywood, there are more promising new girls than ever before! And at least two of them are apparently being groomed “to take Clara Bow’s place.”

Then he listed several of them, most of whose names will be at least vaguely familiar to any self-respecting classic-movie buff. Valentine emphasized that any one of them might supplant Clara as “the spirit of youth” (Clara herself was still only 26), so I’ll take them more or less in descending order of their ages as of May ’31, with some of Valentine’s remarks:

Sidney Fox (23 years, 5 months) “…very young…brunette, with lovely big dark eyes, and a warmth and sweetness to her that the camera will gulp in great big bites. She’s Universal’s find, and Junior Laemmle has big things in store for her.” As things turned out, Sidney Fox became one of Hollywood’s sad cases. Petite (only 4′ 11″) and (as Valentine suggests) angel-faced, she made a name for herself in a couple of Broadway plays. That brought her to the attention of Carl Laemmle Jr., who signed her for Universal. She made her film debut in The Bad Sister, released just two months before this article. Based on Booth Tarkington’s 1913 novel The Flirt, it was also the debut of Bette Davis — and oddly enough, it was Fox who had the title role; Davis was her timid older sister. Sidney Fox’s best-remembered picture is 1932’s Murders in the Rue Morgue (she was even billed over Bela Lugosi), but she’s not what it’s remembered for. Gossip had her carrying on with Junior Laemmle (some even linked her with Carl Senior as well), and she became damaged goods. Marriage in 1932 to a Universal story editor was stormy and abusive, and a couple of European pictures in 1933 failed to reignite her career. Her fifteenth and final picture came in 1934; after that there was a little stage and radio work, but the game was pretty much up. Ill and depressed, she decided to call it a day in 1942 with an overdose of sleeping pills. She was 34.

Sidney Fox (23 years, 5 months) “…very young…brunette, with lovely big dark eyes, and a warmth and sweetness to her that the camera will gulp in great big bites. She’s Universal’s find, and Junior Laemmle has big things in store for her.” As things turned out, Sidney Fox became one of Hollywood’s sad cases. Petite (only 4′ 11″) and (as Valentine suggests) angel-faced, she made a name for herself in a couple of Broadway plays. That brought her to the attention of Carl Laemmle Jr., who signed her for Universal. She made her film debut in The Bad Sister, released just two months before this article. Based on Booth Tarkington’s 1913 novel The Flirt, it was also the debut of Bette Davis — and oddly enough, it was Fox who had the title role; Davis was her timid older sister. Sidney Fox’s best-remembered picture is 1932’s Murders in the Rue Morgue (she was even billed over Bela Lugosi), but she’s not what it’s remembered for. Gossip had her carrying on with Junior Laemmle (some even linked her with Carl Senior as well), and she became damaged goods. Marriage in 1932 to a Universal story editor was stormy and abusive, and a couple of European pictures in 1933 failed to reignite her career. Her fifteenth and final picture came in 1934; after that there was a little stage and radio work, but the game was pretty much up. Ill and depressed, she decided to call it a day in 1942 with an overdose of sleeping pills. She was 34.

Lillian Bond (23 years, 4 months) “A sweet little siren with irreproachable diction and frank ambitions to create a new type of vamp on the screen.” Actually, the name was Lilian, though for much of her career she was billed with the double-L. Those vamp ambitions never quite materialized, but Bond gave it a decent shot. A couple of classics: she played Charles Laughton’s chorus-girl squeeze in James Whale’s The Old Dark House (1932), and contributed a memorable cameo as Lily Langtry in the last scene of William Wyler’s The Westerner opposite Gary Cooper and Walter Brennan. Apart from that, it was mostly supports and bits, sometimes uncredited, then a sprinkling of television work before she retired from acting in 1958. She died in 1991, age 83.

Lillian Bond (23 years, 4 months) “A sweet little siren with irreproachable diction and frank ambitions to create a new type of vamp on the screen.” Actually, the name was Lilian, though for much of her career she was billed with the double-L. Those vamp ambitions never quite materialized, but Bond gave it a decent shot. A couple of classics: she played Charles Laughton’s chorus-girl squeeze in James Whale’s The Old Dark House (1932), and contributed a memorable cameo as Lily Langtry in the last scene of William Wyler’s The Westerner opposite Gary Cooper and Walter Brennan. Apart from that, it was mostly supports and bits, sometimes uncredited, then a sprinkling of television work before she retired from acting in 1958. She died in 1991, age 83.

Sylvia Sidney (20 years, 9 months) “Lovely. Lush. Terribly young. Terribly keen, and smart. Knowing in the New York manner. Sure of herself — a little too sure, maybe; but so exquisite you can’t worry about that.” In fact, Sylvia Sidney had already replaced Clara Bow on one picture, City Streets opposite Gary Cooper, released the month before Valentine’s article appeared. We all know what became of her: She went the distance in every sense. She never quite made it to superstardom, but she was a star, no error, and she worked steadily for over 60 years with directors from Josef von Sternberg, Henry Hathaway and Fritz Lang to Tim Burton, Wim Wenders and Joan Micklin Silver. Her last performance was in 1998 on the rebooted Fantasy Island TV series (with Malcolm McDowell as Mr. Roark) and she died at 88 in 1999 — no doubt still looking forward to her next job.

Marian Marsh (17 years, 7 months) “…the lovely little girl who looks like Dolores Costello with a dash of Constance Bennett, and who has been chosen by John Barrymore to play opposite him in ‘Svengali.'” “Marian Marsh” first came into existence when this young actress signed with Warner Bros. (born Violet Krauth, she had made a few minor film appearances as Marilyn Morgan). That Svengali gig, which went into release the month Valentine’s article appeared, was a good beginning. Barrymore did indeed choose her to play Trilby for her resemblance to his wife Dolores Costello, and he reportedly coached her throughout production (we all know what that can mean; read Mary Astor’s autobiographies). She had a good run for several years, first at Warners’, then Columbia, Paramount and RKO, before winding up on Poverty Row at Monogram and rock-bottom PRC. She retired from acting at age 30 (except for a couple of TV one-shots in the 1950s). Eventually, she settled in Palm Desert, Calif., a town founded by her second husband Cliff Henderson, and she in turn founded Desert Beautiful, a nonprofit conservation organization. She outlived Henderson by 22 years, dying at 93 in 2006.

So those were some of Sydney Valentine’s candidates for The Next “It” Girl. But the one he mentioned first, gave pride of place, was Carman Barnes (18 years, 6 months) “Something brand new — exciting — with a dash of the exotic, too. In fact, if you can imagine anything so fantastic — if there could be a combination of Garbo, Dietrich and Bow, Carman is it!”

So those were some of Sydney Valentine’s candidates for The Next “It” Girl. But the one he mentioned first, gave pride of place, was Carman Barnes (18 years, 6 months) “Something brand new — exciting — with a dash of the exotic, too. In fact, if you can imagine anything so fantastic — if there could be a combination of Garbo, Dietrich and Bow, Carman is it!”

Whew! Down, boy!

You may look in vain for Carman Barnes on the Internet Movie Database; she’s not there. Now of course, Hollywood history has plenty of would-be superstars whose careers failed to live up to their studios’ or producers’ plans for them. Sam Goldwyn brought Ukrainian-born Anna Sten over from Germany heralding her as “the new Garbo”; she bombed. At MGM, Arthur Freed’s protégée Lucille Bremer was groomed for stardom (partly as a ploy to keep Judy Garland in line), but the public simply wouldn’t have her. Well, the public never got to weigh in on Carman Barnes; her career as a movie star ended before she appeared on even so much as a single frame of film. But Paramount (Clara Bow’s studio, and Sylvia Sidney’s) gave her quite the media blitz in the early months of 1931. There has never been a bigger buildup with less follow-through.

Carman Dee Barnes was born on November 20, 1912 in Chattanooga, Tennesee, to James Hunter Neal, a “wealthy manufacturer”, and his wife Lois Diantha Mills Neal, a lyric poet and writer of mountain folklore who published under the name Diantha Mills. Whether Carman’s mother became widowed or divorced I wasn’t able to learn (divorced, probably). In any case, she remarried Wellington Barnes, founder and treasurer of Chattanooga’s Dixie-Portland Cement Co., and daughter Carman took his surname as her own.

Carman was an only child, and precocious; in interviews she said she “cannot remember the time when she did not know how babies are born.” A sickly child, “always having measles or whooping cough or pneumonia or something”, she spent much of her childhood indoors — first reading voraciously (Bertrand Russell and W. Somerset Maugham became favorites), then writing (“Long, elaborate stories about love and tragedy and divorce and all. They were very funny.”).

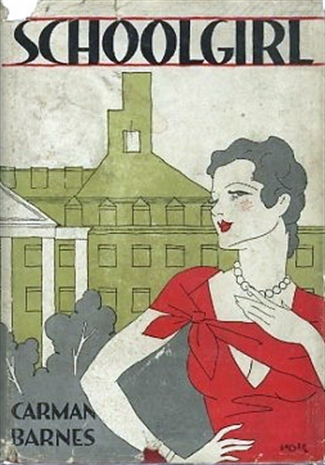

By the time she was 15 those around her began to notice that she did in fact have a way with the written word. One friend gave her the usual advice: Stop writing about love triangles until you know something about them; write what you know. All Carman really knew at that point was attending boarding school, first Girls’ Preparatory School in Chattanooga, then the Ward-Belmont School for Girls in Nashville. So during her summer vacation from Ward-Belmont in 1928 she decamped to this cozy cabin on the left, her family’s summer retreat (quaintly dubbed Once Upon a Time) on Tennessee’s Lookout Mountain. There she wrote a novel (“I’m not awfully interested in the short story form.”); she called it Schoolgirl.

By the time she was 15 those around her began to notice that she did in fact have a way with the written word. One friend gave her the usual advice: Stop writing about love triangles until you know something about them; write what you know. All Carman really knew at that point was attending boarding school, first Girls’ Preparatory School in Chattanooga, then the Ward-Belmont School for Girls in Nashville. So during her summer vacation from Ward-Belmont in 1928 she decamped to this cozy cabin on the left, her family’s summer retreat (quaintly dubbed Once Upon a Time) on Tennessee’s Lookout Mountain. There she wrote a novel (“I’m not awfully interested in the short story form.”); she called it Schoolgirl.

Mama Diantha was pretty proud of her daughter for turning out a 47,000-word novel over one summer at the age of 15, and — perhaps cashing in a few chips’ worth of her regional literary reputation — she submitted Carman’s manuscript to publisher Horace Liveright in New York. Carman turned 16 that November and a month later, while she was decorating the family Christmas tree, she received a telegram that Boni & Liveright had accepted Schoolgirl for publication.

Carman’s mother also deserves points for (if nothing else) maternal aplomb. If Carman actually did take that friend’s advice about writing what she knows…well, many mothers in 1928 would have been pretty startled by what this youngster knew at that age, and in those days.

Schoolgirl tells the story of Naomi Bradshaw, a 16-year-old southern belle with a string of boys on the line. When a late-night gallivant with one of them — which Naomi, only vaguely understanding what she’s saying, calls an “elopement” — creates a minor scandal in the town, her indulgent but exasperated father ships her off to South Fields Prep, a girls’ school at some distance from her hometown. His hazy notion is that the closely-chaperoned life there will keep her from getting a “reputation”. Naomi throws a half-hearted tantrum about it, but the fact is she’s half looking forward to the change.

At South Fields Naomi has no trouble slipping into the social life — the “societies”, the clandestine parties after lights-out, the chaperoned outings and secret dates with boys from the town. The girls are housed two to a room, with each two-room suite sharing a bathroom. Naomi’s suite-mates are sisters Celia and Margie Morgan; her roommate is Janet Livingston (“Her eyes were kind and hazel, her mouth full, with a tender, lovable beauty.”).

Olive, one of the girls in Naomi’s dorm, casually cautions her about “crushes”: “Everybody has a crush sooner or later when they go off to school…oh, not a desperate one with petting and all, but just sort of a stage-struck, tongue-tied friendship, admiring a girl from a distance and all.” At the thought, Naomi feels “weak, repulsed, horrified”, but as the term wears on — there’s no other way to put it — she falls in love with Janet Livingston, with all the attendant insecurity and petty jealousies. When she learns that Janet “went the distance” with Jerry, her boyfriend back home, Naomi follows suit in short order, losing her virginity to Dave, the boy she’s been dating on the sly when the watchful eyes of the school were looking the other way:

…His breath against her ear, the force of his strength, his masculinity, his love crashing through her resistance.

No, it couldn’t be put into words. It wasn’t altogether passion, Naomi was sure — not all passion — but love, this exultant, flaming thing that swept her off her feet, and lifted her out of herself. She wasn’t afraid now, but the fire of fierce desire had weakened her, had made her heedless. It seemed to be the most natural thing in the world.

Despite Naomi’s “ecstatic joy” at “being thrilled by the right kind of thrill”, the subtext is clear: She takes this step not to get closer to Dave, but to feel closer to Janet, and Naomi’s most passionate moments are with her:

Frantically she drew Janet’s yielding form nearer her own, felt the rise and fall of Janet’s firm, rounded bosom surging with the emotion of remembered pleasures, and her lips met Janet’s in wild longing. Soft, soft lips! Naomi was awed by their warm tenderness. Dave’s — Dave’s had been hard and fiercely demanding. Janet’s were like the velvet petals of a flower, a red, red — dark red — flower!

This is headlong stuff for a 15-year-old in 1928. Much of Schoolgirl may strike modern readers as old-fashioned — the slang, the social customs — but no two ways about it: the kid could write.

Schoolgirl‘s episodes of sexual experimentation are about as explicit as respectable fiction could get in the 1920s — remember, the word “obscenity” was thrown around much more freely in those days, and it was still a crime to send it through the mail — and the novel’s eye-opening frankness made it a bestseller, and Carman Barnes a celebrity. A second novel, Beau Lover in 1930, gave evidence that Schoolgirl had been no fluke, and later that year Carman collaborated with Alfonso Washington Pezet on a stage adaptation of Schoolgirl, to be produced on Broadway in the fall. Carman was still only 17.

Then Paramount came calling. We’ll get into that next time.

To be continued…