Luck of the Irish: Darby O’Gill and the Little People, Part 1

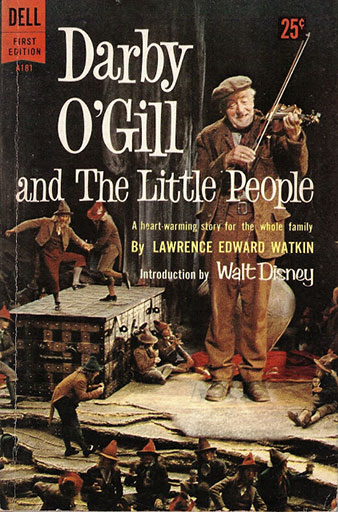

In 1962, if I had known that the actor playing James Bond was the same actor who played Michael McBride in Darby O’Gill and the Little People, I might have taken the trouble to see Dr. No sooner than I did. But in all the publicity surrounding the screen debut of Ian Fleming’s secret agent, and the handsome young discovery of producers Harry Saltzman and Albert Broccoli, there was scant mention (if any) of the picture Sean Connery had made for Walt Disney three years earlier. Small wonder: Darby O’Gill was a flop.

In 1962, if I had known that the actor playing James Bond was the same actor who played Michael McBride in Darby O’Gill and the Little People, I might have taken the trouble to see Dr. No sooner than I did. But in all the publicity surrounding the screen debut of Ian Fleming’s secret agent, and the handsome young discovery of producers Harry Saltzman and Albert Broccoli, there was scant mention (if any) of the picture Sean Connery had made for Walt Disney three years earlier. Small wonder: Darby O’Gill was a flop.

The picture was never a flop as far as I was concerned. I loved it in 1959 when I saw it at the Stamm Theatre in Antioch, Calif. I loved it in 1960 when I read this novelization by Lawrence Edward Watkin of his own screenplay. And when it was reissued in ’69 (on a double bill with Dick Van Dyke and Edward G. Robinson in Never a Dull Moment) I went to see it almost every night it played — wondering with bemusement exactly when Sean Connery got into this movie. I contented myself with one viewing when it was reissued in ’77, but I said then what I say to this day: Darby O’Gill and the Little People is one of Walt Disney’s unsung masterpieces.

Disney himself attributed the picture’s failure to the unusually thick Irish accents of his actors, plus the fact that he was unable to make the picture as he originally planned, with Barry Fitzgerald playing the double role of Darby O’Gill and King Brian of the leprechauns. Maybe so, but personally, I think that in the long run the movie dodged a bullet. Barry Fitzgerald and softer brogues might have made Darby a bit more of a hit, but they would have made it much less of a masterpiece. (I’ve read that for some releases the dialogue was redubbed with more America-friendly voices, but if so I never saw or heard any of those prints. Thank God.)

To be continued…

Luck of the Irish: Darby O’Gill and the Little People, Part 2

With this title card at the opening of Darby O’Gill and the Little People, Walt Disney doubled down on the premise behind the broadcast of his weekly television show on May 29, 1959. (The official name of the series had changed to Walt Disney Presents in the fall of ’58, but everybody I knew still called it Disneyland.) On that episode, titled “I Captured the King of the Leprechauns”, Disney recounted to his Irish-American friend, actor Pat O’Brien, the research and negotiation behind the production of Darby O’Gill. Research in the form of a visit to Ireland to confer with scholars of Irish folklore; negotiation in the form of an arranged meeting with King Brian himself to offer him and his minions roles in the picture Disney was planning.

From the “scholar of Irish folklore” he consults, Disney learns the story of how the leprechauns came to Ireland. What the man tells him is a tale straight out of Herminie Kavanagh’s book — I’ve found it nowhere else in print, so it’s likely she created it herself — and it goes like this: King Brian and his followers are fallen angels, casualties of the revolt of Satan in Heaven before the beginning of time. Too small and timid to engage in the fighting, they hid under the Golden Steps until Satan and his minions were defeated and cast into Hell. Confronting King Brian after the battle, the Archangel Gabriel told him, “An angel who won’t stand up and fight for what he knows is right may not be deserving of Hell, but he’s not fit for Heaven.” So Brian and the rest were banished to live on the Earth, but were mercifully granted leave to settle in a place of their choice. They chose what came to be known as Ireland because it was the closest thing to Heaven that they could find on Earth.

To be continued…

Luck of the Irish: Darby O’Gill and the Little People, Part 3

But once you adjust to these idiosyncracies (especially if you can assume the accent and read the stories aloud), there’s an unassuming poetry to the tales that can sometimes take your breath away. Describing one fine morning, the narrator (it’s hinted that he’s a Kilkenny cabbie and the son of a cousin of Darby’s) says, “‘Twas one of those warm-hearted, laughing autumn days which steals for a while the bonnet and shawl of the May.” What more do we need to hear to know exactly the sort of day it was?

Another time, Darby O’Gill’s wife Bridget boasts to other wives of the village that her husband is so brave that he doesn’t fear to leave the house on Halloween Night, when “all the worruld” knows that ghosts are afoot. To prove her point (and save face), even as a fierce storm rages that very night, Bridget resolves to cajole Darby into taking “a bit of tay” to poor young Eileen McCarthy, who lies near death. At first Darby resists — “We have two separate ways of being good. Your way is to scurry round an’ do good acts. My way is to keep from doing bad ones. An who knows which way is the betther one. It isn’t for us to judge.” But when he finally agrees to go out, a relieved Bridget encourages him in this lovely passage:

There’s nothing puts so much high courage and clear steadfast purpose in a man’s heart, if it be properly given, as a kiss from the woman he loves. So, with the warmth of that kiss to cheer him, Darby set his face against the storm.

There are countless rough-jeweled passages like that in Mrs. Kavanagh’s prose — I laughed out loud at “One could have scraped with a knife the surprise off Darby’s face” — but you get the idea. How to preserve the delicate humor of the stories, the palpable sense of a happy home and hearth, the simple yet ardent faith, the merry yet mischievous friendship between Darby and King Brian, was what Lawrence Edward Watkin wrestled with between assignments from the day Disney hired him.

Because Darby O’Gill is rarely considered one of Disney’s major pictures, there is scant published documentation of its development and production. Two major biographies, Neal Gabler’s Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination and Michael Barrier’s The Animated Man, have only two cursory mentions between them. Peter Ellenshaw’s coffee-table memoir Ellenshaw Under Glass goes into detail about his visual effects work (which I covered in Part 2), and he says that both Bill Walsh and Don DaGradi (who later shared an Oscar nomination for their Mary Poppins screenplay) worked on the script. (In the finished picture DaGradi is credited only for “Special Art Styling”, Walsh not at all. It may be that Walsh — like DaGradi, one of Disney’s most trusted lieutenants — worked uncredited on the script; it’s also possible that Ellenshaw, writing in 2003, conflated Darby O’Gill with his later work with Walsh and DaGradi on Mary Poppins.)

We do, at least, have testimony from Walt Disney himself, in the form of his introduction to the Darby O’Gill novelization. (The intro was ghost-written, no doubt, but it’s a cinch it wouldn’t have gone to the printer until Walt approved it.) He says that it was “in 1945, I believe” that Herminie Kavanagh’s stories first came to his attention, prompting a trip to Ireland to get a feel for the land.

Disney did indeed visit Ireland and Great Britain in November 1946, and again for a longer stay from June to August ’49. His leprechaun movie might have been on his mind both those times. In ’46 he had spoken to Hollywood columnist Hedda Hopper about plans for Alice in Wonderland (to be done with a live-action Alice played by little Luana Patten of Song of the South, and set in an animated Wonderland) as well as for The Little People, to be set in Ireland.

But it’s unlikely that Herminie Kavanagh’s Darby O’Gill stories were foremost in his mind even then. The Disney Studio was drifting after the end of World War II — strapped for money, still recovering from the bitter trauma of a strike in the early ’40s (which Disney took very personally), and uncertain how to move forward. Of more immediate concern, no doubt, was how the cash-poor studio could make use of the millions of pounds sterling that had piled up from features and shorts playing in the U.K. during the war; money that Disney sorely needed but which, due to currency restrictions imposed by Parliament, couldn’t be taken out of the country.

|

| DR. JAMES HAMILTON DELARGY |

The liberties began with the mountain location of King Brian’s underground castle. Herminie Kavanagh gave it as Slieve-na-mon (usually spelled without the hyphens), a 2,363-ft. peak in southern County Tipperary, near Clonmel. Watkin moved King Brian’s court about 22 miles southwest, to Knocknasheega in County Waterford — possibly for its less cumbersome and more poetic-sounding name. But the change didn’t stop there; here’s a view of 1,404-ft. Knocknasheega as it is in real life…

Darby O’Gill’s village has no name in Kavanagh; in the movie it’s Rathcullen. After an exhaustive Internet search, I could find no village by that name, only a real estate listing for a single house on a half-acre of land “nestling between Aherla [pop. 450] & Cloughduv [pop. 300] Villages” in County Cork. (There’s also a Web site for a Rathcullen Lounge in Killarney, County Kerry, which for all I know may have taken its name from the movie.) So let’s take it as given that Rathcullen and the neighboring village of Glencove are both creations of Lawrence Edward Watkin.

So are most of the characters. In the stories, Darby’s age is never mentioned, but his wife Bridget is still alive, his children (at least four of them) are still small, and the narrator often calls Darby “the lad”. Watkin made him an elderly widower with only his grown daughter Katie. While Darby’s livelihood is hardly hinted at in Kavanagh, in the movie he’s caretaker on the country estate of Lord Fitzpatrick (Walter Fitzgerald) — “but he retired about five years ago,” says his lordship, “didn’t tell me about it.” That’s why Lord Fitzpatrick has hired Michael McBride (Sean Connery) to replace him, intending to retire Darby on half pay, with free use of a small cottage on the property for the rest of his days. Darby wheedles his lordship into letting him break the news to Katie himself, and when Lord Fitzpatrick leaves, Darby introduces Michael to Katie as a new hired hand. Darby’s scheming to keep the truth from Katie as long as possible, along with his later kidnapping of King Brian, are the twin threads that will come together at Darby O’Gill‘s ghostly climax.

To be concluded…

Luck of the Irish: Darby O’Gill and the Little People, Part 4

Michael Barrier’s The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney makes only one mention of Darby O’Gill and the Little People — and in a footnote, at that — but it gives something like credit where it’s due, calling it “a film rich in Irish atmosphere but shot entirely in California.” Surprising as it sounds, it’s true; every frame of Darby O’Gill was shot at the Disney Studios in Burbank or about 30 miles up Highway 101 in Triunfo and Canoga Park. Much of the atmosphere commended by Barrier is to the credit of Peter Ellenshaw and the great cinematographer Winton C. Hoch; between them they were able to transmute the golden glimmer of sunny Southern California into the cloudy and cool green glow of the Emerald Isle — literally, “Irish atmosphere”.

Then there’s the cast, all of them either unfamiliar or entirely unknown, thus bearing few overt traces of Hollywood — the way, frankly, Barry Fitzgerald would have done. (Even the future Sir Sean Connery was so young at the time — he turned 29 during shooting — that he doesn’t particularly stand out from the pack even today.) Most of the actors are authentically Irish. I’ve already mentioned Albert Sharpe, Jimmy O’Dea and Kieron Moore; there were also Denis O’Dea as Father Murphy, the village priest; J.G. Devlin, Farrell Pelly and Nora O’Mahoney as Darby’s drinking companions at the Rathcullen Arms; and Jack MacGowran as Phadrig Oge, King Brian’s trusted lieutenant. The rest were either Celtic — the Scottish Connery and Janet Munro — or English of Irish ancestry, like Walter Fitzgerald as Lord Fitzpatrick. (Fitzgerald and O’Dea were both veterans of Disney’s Treasure Island, as Squire Trelawney and Dr. Livesy respectively.)

One tradition of Irish folklore that Watkin most likely picked up from that Dublin commission — because it’s not mentioned in Kavanagh — says that as long as music is playing, a leprechaun can’t stop dancing; this stands Darby O’Gill in good stead when King Brian puts the come-hither on him and traps him in his mountain lair. In the first of Herminie Kavanagh’s stories, the same thing happens — she calls the spell the “comeither” — but there, Darby is held in gentle captivity for six months, finally escaping with the help of his sister-in-law, who is likewise enchanted. For a number of reasons (six months!) this would never do for the movie, so Watkin shortened Darby’s sentence to a single night. Darby offers to fiddle the Little People a tune, which sets them dancing. He fiddles faster and faster until they leap to their horses (see the end of Part 2) and gallop off into the night through a magical fissure that King Brian opens in the side of the mountain; the fissure remains open just long enough for Darby to make good his escape.

“Costa Bower” is how Herminie Kavanagh spells it, and so does Watkin in his novelization. A more accurate spelling from the Gaelic is “Coiste Bodhar” — pronounced “Coash-ta Bower”, as it is in Darby O’Gill. In Kavanagh’s story, the Costa Bower carries Darby and King Brian to a rendezvous with the Banshee so Darby can return her golden comb, which he has inadvertently pilfered; on the way they have quite a pleasant conversation with the driver — or rather, with his head, which sits on the seat beside him. The coachman reminisces about his mortal life “three or four hundhred years ago”, and it comes to light that he languished and died — a suicide, perhaps, which would explain his present employment — for love of “purty” Margit Ellen O’Gill, an ancestor of Darby’s. Small world, eh?

In Watkin’s screenplay, the Costa Bower’s mission is more in line with folklore: it’s coming to convey a departed soul to its final reward. Knowing it comes for Katie, Darby tries to use his third wish to send it away, but such a thing is not within King Brian’s powers; once the Costa Bower sets out for Earth it can never return empty. Then let it take me instead, Darby cries; that’s my third wish. King Brian shakes his head ruefully; “More’s the pity. Granted.”

When the coach arrives, its headless driver (unlike in Kavanagh’s story) is not inclined to idle chat, and utters only four words: “Darby O’Gill? Get in.”

Darby O’Gill and the Little People is a veritable catalogue of Irish folklore, nearly all of it presented matter-of-factly and without explanation, as if the audience — like Darby’s listeners in the Rathcullen Arms — had been raised on these traditions and knew them in their bones. From its early scenes of good-natured competition between Darby and King Brian, the story descends into a literal life-and-death struggle with the dark forces Darby’s meddling has unleashed. At the same time, on a more earthly level, the underhanded scheming of Sheelah and Pony Sugrue bears fruit that makes Darby’s, Katie’s and Michael’s situation all the more dire. Leonard Maltin’s “little short of brilliant” appraisal of the script may be an understatement. His other appraisal is right on the money: “Darby O’Gill and the Little People is not only one of Disney’s best films, but is certainly one of the best fantasies every put on film.”

As I mentioned at the beginning of these posts, Darby O’Gill was a flop. Even as a flop it was overshadowed by Disney’s costlier and higher-profile box office disappointment of 1959, Sleeping Beauty. (Only the unexpected bonanza of The Shaggy Dog enabled the Disney Studios to turn a tidy profit that year.)

Disney may have had a point when he suggested that Darby‘s extreme Irishness was its undoing in 1959, but it made it all the more unique and remarkable. Disney’s Pinocchio, on its release in 1940, was criticized for the way it turned Carlo Collodi’s creation into a generically American boy (although anybody who tries to read that dreadful, preachy, grisly book knows that Disney did more for Collodi than Collodi ever did for him). Likewise with Mary Poppins; while I yield to no one in my admiration for Disney’s classic, admirers of P.L. Travers’ books (beginning with Travers herself) have long scorned the movie — and in any event, no one could ever mistake it for an accurate picture of Edwardian London.