Films of Henry Hathaway: Fourteen Hours (1951)

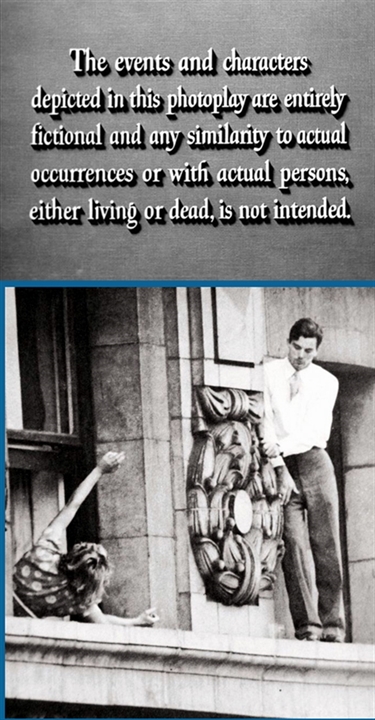

This title card appears early in Henry Hathaway’s Fourteen Hours — at the “climax” of the opening credits, you might say, just before the credit cards for producer Sol C. Siegel and director Hathaway. It’s the standard “entirely fictional and any similarity” disclaimer, the kind that usually appears in super-small type somewhere near the copyright notice, the MPAA “approved” certificate number, the Western Electric and IATSE credits, and other things that are legally required but nobody really cares if you see or not. For this picture, though, 20th Century Fox took the unusual step of making sure the disclaimer was very prominently placed where even the most inattentive could hardly miss it.

This title card appears early in Henry Hathaway’s Fourteen Hours — at the “climax” of the opening credits, you might say, just before the credit cards for producer Sol C. Siegel and director Hathaway. It’s the standard “entirely fictional and any similarity” disclaimer, the kind that usually appears in super-small type somewhere near the copyright notice, the MPAA “approved” certificate number, the Western Electric and IATSE credits, and other things that are legally required but nobody really cares if you see or not. For this picture, though, 20th Century Fox took the unusual step of making sure the disclaimer was very prominently placed where even the most inattentive could hardly miss it.

The studio didst protest too much; the disclaimer was disingenuous. Fourteen Hours was generally fictional, but not entirely, and its similarity to “actual occurrences” and “actual persons” was fully intended.

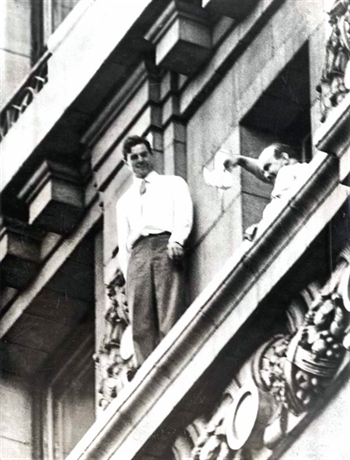

Here’s Exhibit A. This isn’t a still from the movie, it’s a news photo from real life, taken on Tuesday, July 26, 1938. The man is 26-year-old John William Warde; the woman is his sister Katherine, 22. On that day, John and Katherine were visiting friends, a Mr. and Mrs. Valentine, who lived in Room 1714 of New York’s Gotham Hotel. Sometime around 10:30 in the morning, after John, Katherine and Mrs. Valentine had ordered lunch from Room Service, John calmly announced, “I’m going out the window.” And as the two women stared dumbfounded, he did. In a panic, Katherine phoned the front desk, screaming that her brother had jumped out the window — but he had only clambered out onto the ledge. And there he stayed while a crowd of spectators gathered in the street 170 feet below, traffic came to a standstill, and police emergency crews scrambled to coax, cajole or drag him to safety. Hoping to talk him in, NYPD traffic cop Charles Glasco chatted with Warde disguised as a hotel bellhop (Warde had threatened to jump if any cop came near him). Warde, who had attempted suicide before and been diagnosed with “manic-depressive psychosis” (that era’s term for bipolar disorder), resisted every effort. “I’ve got to work things out for myself,” he kept saying, “I’ve got problems to think about.”

That, in a nutshell, is the story of that day in 1938, and it’s also the premise of Fourteen Hours. This lobby card even eerily mirrors the photo — although the characters here aren’t brother and sister, they’re Robert Cosick (Richard Basehart) and Virginia Foster (Barbara Bel Geddes), his ex-fiancée. The movie’s disclaimer is further belied by its writing credit: “Screen Play by John Paxton From a Story by Joel Sayre”. The “story” was an article by Sayre, “That Was New York: The Man on the Ledge”, which appeared in The New Yorker on April 16, 1949, chronicling John Warde’s story. And the picture’s original working title was The Man on the Ledge, just like Sayre’s factual article. (As for why the title was changed, I’ll get to that later.)

So much for those supposedly not-intended similarities; some of them, anyhow. It’s the differences between real life and the movie that make Fourteen Hours so interesting.

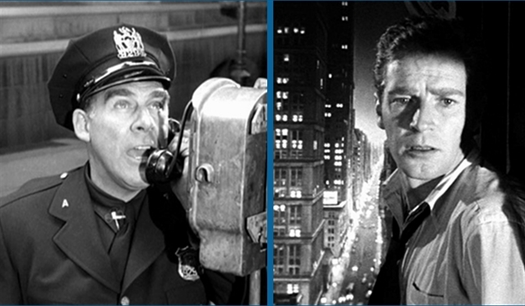

The picture opens quietly — in silence, in fact, without dialogue or even background music. (Indeed, except for Alfred Newman’s fervid theme under the opening credits, then a second theme swelling through the movie’s last 90 seconds, there’s no music in the entire picture.) We are introduced to what will prove to be the two central characters in the drama that follows. First we see Patrolman Charlie Dunnigan (Paul Douglas as the movie’s version of Charles Glasco) walking his beat in the early morning calm. He passes the Rodney Hotel, where a worker is polishing the brass plate at the entrance. Meanwhile, up in Room 1505…

The picture opens quietly — in silence, in fact, without dialogue or even background music. (Indeed, except for Alfred Newman’s fervid theme under the opening credits, then a second theme swelling through the movie’s last 90 seconds, there’s no music in the entire picture.) We are introduced to what will prove to be the two central characters in the drama that follows. First we see Patrolman Charlie Dunnigan (Paul Douglas as the movie’s version of Charles Glasco) walking his beat in the early morning calm. He passes the Rodney Hotel, where a worker is polishing the brass plate at the entrance. Meanwhile, up in Room 1505…

…a room service waiter (Frank Faylen) is delivering a breakfast tray to a guest registered as William E. Cook of Philadelphia, but who is really Robert Cosick (Basehart). He hands the waiter some cash, and the waiter turns his back to count out his change on a tray. When he turns back, the room is empty. He checks the closet, then the bathroom. He notices the curtains billowing at the open window. Glancing out, he sees the missing guest standing on the ledge, breathing heavily, looking agitated.

Then the silence is rudely broken by the first human sound we hear — a secretary screaming in the window of a bank building across the street. Dunnigan dashes into the hotel to alert the staff, while the waiter calls down to the switchboard for the same reason. Dunnigan and Harris, the assistant manager (Willard Waterman), knowing now which room to go to, head up in the elevator. In the room, Harris blusters at Robert to come inside, sounding like an impotent scold.

Then the silence is rudely broken by the first human sound we hear — a secretary screaming in the window of a bank building across the street. Dunnigan dashes into the hotel to alert the staff, while the waiter calls down to the switchboard for the same reason. Dunnigan and Harris, the assistant manager (Willard Waterman), knowing now which room to go to, head up in the elevator. In the room, Harris blusters at Robert to come inside, sounding like an impotent scold.

Down in the street, pedestrians are beginning to gather. The first two we see idly wonder if this is some kind of advertising stunt. Patrol cars screech to a halt at the hotel entrance, sirens blaring. Up in 1505, Robert warns Harris that if a cop comes near him, he’ll jump. Hearing that, Dunnigan commandeers Harris’s necktie to disguise his own uniform, then sits on the window sill, trying to strike up a conversation with the distraught Robert.

The colloquy between Charlie Dunnigan and Robert Cosick, a mixture of urgent pleading and forced-casual chitchat, provides the spine of Fourteen Hours, just as the real one between Charles Glasco and John Warde did for Joel Sayre’s New Yorker article. (Notice too how Joe MacDonald’s deep-focus photography emphasizes both men’s perilous perch 15 stories up. MacDonald was a master cinematographer who worked with Hathaway on nine pictures, including some of his best.)

The colloquy between Charlie Dunnigan and Robert Cosick, a mixture of urgent pleading and forced-casual chitchat, provides the spine of Fourteen Hours, just as the real one between Charles Glasco and John Warde did for Joel Sayre’s New Yorker article. (Notice too how Joe MacDonald’s deep-focus photography emphasizes both men’s perilous perch 15 stories up. MacDonald was a master cinematographer who worked with Hathaway on nine pictures, including some of his best.)

Over this bare factual skeleton Paxton’s script skillfully weaves a variety of fictional stories among the people drawn for one reason or another to the Rodney Hotel and the street outside. It amounts to a cross-section of the New York public circa 1950 — and for all the changes the city has seen in 69 years, it still rings true today.

Over this bare factual skeleton Paxton’s script skillfully weaves a variety of fictional stories among the people drawn for one reason or another to the Rodney Hotel and the street outside. It amounts to a cross-section of the New York public circa 1950 — and for all the changes the city has seen in 69 years, it still rings true today.

Caught in the traffic jam down in the street are several cab drivers, unable to move their vehicles and looking at a day with no fares. “If I had my M-2 I could knock him off from here, clean,” says one of them (Harvey Lembeck). (And by the way, the African American gentleman is the great Ossie Davis, at the very beginning of his long career.) Another cabbie grumbles that if the guy wants to jump he should go ahead so the rest of New York can get on with their business. “Who cares? I figured on a good day today.”

Later on, this same sour cabbie suggests they should all pony up a buck for a pool and pick an hour; “the guy that gets closest to the time this joker jumps, that guy wins the pot.” His fellows are uneasy at his ghoulish idea, but they all go along.

Elsewhere in the crowd the reaction is more compassionate. Two young office workers, Ruth (Debra Paget, left) and Barbara (Joyce Van Patten, right), have gotten sidetracked on their way to work. The fretful Barbara wants only to get to work before they get in trouble with the boss. But Ruth is more worried about the stranger on the fifteenth floor: How old is he? What kind of trouble is he in? “Maybe someone was cruel to him, or maybe he’s just lonely…I wish I could help him.” Her tender words catch the ear of Danny behind her (Jeffrey Hunter), also pausing on his way to work. When Barbara gives up and leaves, Danny and Ruth strike up a sweetly tentative conversation. As the day wears on, neither of them will get to work. Feelings grow between them, and Danny reflects on how they might have gone their whole lives, missing each other by minutes, if it hadn’t been for this day. Hunter and the 17-year-old Paget were already launched on their successful careers as Fox contract players. Van Patten, making her film debut at 16, would in time become one of television’s busiest character actresses in a career that is still going strong today.

Elsewhere in the crowd the reaction is more compassionate. Two young office workers, Ruth (Debra Paget, left) and Barbara (Joyce Van Patten, right), have gotten sidetracked on their way to work. The fretful Barbara wants only to get to work before they get in trouble with the boss. But Ruth is more worried about the stranger on the fifteenth floor: How old is he? What kind of trouble is he in? “Maybe someone was cruel to him, or maybe he’s just lonely…I wish I could help him.” Her tender words catch the ear of Danny behind her (Jeffrey Hunter), also pausing on his way to work. When Barbara gives up and leaves, Danny and Ruth strike up a sweetly tentative conversation. As the day wears on, neither of them will get to work. Feelings grow between them, and Danny reflects on how they might have gone their whole lives, missing each other by minutes, if it hadn’t been for this day. Hunter and the 17-year-old Paget were already launched on their successful careers as Fox contract players. Van Patten, making her film debut at 16, would in time become one of television’s busiest character actresses in a career that is still going strong today.

Needless to say, New York’s newshounds are also Johnny-on-the-spot. Newspapermen swarm over the scene like ants on a sugar cube. New York announcer George Putnam, playing himself, gives a play-by-play summary from a radio truck in the street. Another radio reporter barges into Room 1505 to jam a microphone out the window to eavesdrop on Dunnigan and Robert’s conversation — only to get the bum’s rush from the vigilant police. Station WNBC dispatches a television camera crew to the roof of a building across the street from the hotel. (Curiously enough, this wasn’t just an embellishment in Paxton’s script. NBC really did broadcast TV coverage of John Warde’s exploit back in 1938, even though there probably weren’t more than a few dozen sets in the whole city, and practically none in the rest of the country. It may well have been the very first example of television covering a breaking news story.)

Needless to say, New York’s newshounds are also Johnny-on-the-spot. Newspapermen swarm over the scene like ants on a sugar cube. New York announcer George Putnam, playing himself, gives a play-by-play summary from a radio truck in the street. Another radio reporter barges into Room 1505 to jam a microphone out the window to eavesdrop on Dunnigan and Robert’s conversation — only to get the bum’s rush from the vigilant police. Station WNBC dispatches a television camera crew to the roof of a building across the street from the hotel. (Curiously enough, this wasn’t just an embellishment in Paxton’s script. NBC really did broadcast TV coverage of John Warde’s exploit back in 1938, even though there probably weren’t more than a few dozen sets in the whole city, and practically none in the rest of the country. It may well have been the very first example of television covering a breaking news story.)

Also making her film debut in Fourteen Hours was 21-year-old Grace Kelly, playing Louise Ann Fuller, on her way to discuss a divorce settlement with her estranged husband (James Warren) and their lawyers in an office overlooking the ongoing crisis. As the legal beagles drone on about the division of community property, Mrs. Fuller is preoccupied with the drama outside the office window; it begins to dawn on her that her own marital problems might not be so irreconcilable after all.

Kelly’s performance here led directly to landing her star-making role in High Noon the following year, but the casting became a bone of contention between Hathaway and Darryl F. Zanuck. Hathaway tested two women for the role, and he wanted Kelly. But Zanuck held out for the other woman — Anne Bancroft, who had just been signed to a Fox contract. As Hathaway acknowledged years later, they were both right, though Bancroft was only 19 and her talent wouldn’t reach full bloom for another ten years. Still, it’s intriguing to imagine how differently the two women’s careers might have gone if Zanuck had won that particular standoff.

While the crowd in the street mills about gawking, wringing their hands, or cracking callous jokes, up on the fifteenth floor things are in a muffled uproar. The NYPD’s rescue efforts are commanded by the officious but efficient Deputy Chief Moksar (Howard Da Silva, left), who coordinates activities while straight-arming a swarm of reporters and dealing with other interfering looky-loos (at one excruciatingly delicate moment, a crackpot preacher bursts into the room bellowing at Robert to kneel and pray). Police psychiatrist Dr. Strauss (Martin Gabel, center) offers on-the-fly advice to Moksar and Dunnigan on Robert’s mental state. Further complications come with the arrival of Robert’s divorced parents — his clutching, hysterical mother (Agnes Moorehead, second right) and feckless alcoholic father (Robert Keith, right), who graphically illustrate the Cosick family dysfunction. (“No wonder he’s cuckoo!” growls Moksar.)

While the crowd in the street mills about gawking, wringing their hands, or cracking callous jokes, up on the fifteenth floor things are in a muffled uproar. The NYPD’s rescue efforts are commanded by the officious but efficient Deputy Chief Moksar (Howard Da Silva, left), who coordinates activities while straight-arming a swarm of reporters and dealing with other interfering looky-loos (at one excruciatingly delicate moment, a crackpot preacher bursts into the room bellowing at Robert to kneel and pray). Police psychiatrist Dr. Strauss (Martin Gabel, center) offers on-the-fly advice to Moksar and Dunnigan on Robert’s mental state. Further complications come with the arrival of Robert’s divorced parents — his clutching, hysterical mother (Agnes Moorehead, second right) and feckless alcoholic father (Robert Keith, right), who graphically illustrate the Cosick family dysfunction. (“No wonder he’s cuckoo!” growls Moksar.)

The last puzzle piece slips into place with the arrival of Virginia Foster (Barbara Bel Geddes), Robert’s ex-fiancée. Strauss and Dunnigan take her aside. Why did she break the engagement?, they ask. “I didn’t, he did,” she says. Why? “He just said that he couldn’t…that he’d make me unhappy…”

Dunnigan: “Did you have a fight?”

Virginia: “No, but he’d get mad…”

Strauss: “What about?”

Virginia: “Whenever I tried to help him…”

Strauss launches into a Freudian spiel about how Robert’s mother couldn’t admit, even to herself, that she never wanted him, so she sublimated by teaching Robert to hate his father — which Robert subconsciously knew was wrong, so he only ended up hating himself. It’s a slick piece of 1950s Psych 101 to explain why Robert is out on that ledge.

BUT…That dialogue exchange among Strauss, Dunnigan and Virginia is a classic piece of Breen Office-era code. Adult audiences in 1951 would have had no trouble reading between those lines, imagining exactly what Robert “couldn’t” do that would make Virginia “unhappy”, and with a little more imagination they could picture what Virginia did to “try to help him” that made him so mad. This plants a suggestion, taboo in 1951, that may still go over viewers’ heads today just as it did the Breen Office’s back then, and for the same reason: they’re not accustomed to reading between the lines.

‘Nuff said.

In early 1950, when Darryl Zanuck decided that Joel Sayre’s human-interest New Yorker piece would make a good picture, he first offered the director’s chair to Howard Hawks. Hawks turned him down. Supposedly, Hawks said that the only way he could make the movie would be to convert it into a mistaken-identity comedy starring Cary Grant — an idea so bizarrely stupid that (if it really happened) it could only have been a ploy by Hawks to make sure Zanuck didn’t try to talk him into saying yes.

Zanuck next turned to Hathaway, who liked Sayre’s story, and Zanuck teamed him with writer John Paxton, a specialist in film noir (Murder, My Sweet, 1944; Crossfire, ’47, for which he was Oscar-nominated). Paxton’s noir credentials explain why the Fourteen Hours DVD was released under the “Fox Film Noir” banner. It doesn’t really resemble a film noir except in Joe MacDonald’s urban black-and-white cinematography; there are few of the customary noir characters or plot elements. It fits more neatly into the group of semi-documentary pictures Hathaway made in the mid-’40s, things like The House on 92nd Street (’45), 13 Rue Madeleine (’46), Call Northside 777 (’48), and Kiss of Death (’47) — that last of which actually straddles the border between semi-doc and noir much more than Fourteen Hours does.

Fourteen Hours was what was known as an A-minus picture — that is, a picture with an A budget but no major stars. The closest thing to one was Paul Douglas, the former sports announcer who had been one of Fox’s most popular and reliable supporting actors since his breakout work as Linda Darnell’s husband in A Letter to Three Wives (’49). In 1950 as Fourteen Hours went into production he was teetering between first and second leads, which he would continue to do for the rest of his life, until his untimely death from a heart attack in 1959 at 52. In Fourteen Hours, top-billed in a first-rate ensemble cast, he carries much of the film as his Charlie Dunnigan tries to lure Robert Cosick literally back from the brink, winging it from moment to moment with a seat-of-the-pants common sense.

Fourteen Hours was what was known as an A-minus picture — that is, a picture with an A budget but no major stars. The closest thing to one was Paul Douglas, the former sports announcer who had been one of Fox’s most popular and reliable supporting actors since his breakout work as Linda Darnell’s husband in A Letter to Three Wives (’49). In 1950 as Fourteen Hours went into production he was teetering between first and second leads, which he would continue to do for the rest of his life, until his untimely death from a heart attack in 1959 at 52. In Fourteen Hours, top-billed in a first-rate ensemble cast, he carries much of the film as his Charlie Dunnigan tries to lure Robert Cosick literally back from the brink, winging it from moment to moment with a seat-of-the-pants common sense.

Douglas essentially split leading-man duties with Richard Basehart as Robert Cosick. Basehart had been earning positive notice ever since his debut in 1947’s Repeat Performance. His good buzz gained momentum with his performance in He Walked by Night (’48) as a petty criminal and cop-killer. After Fourteen Hours he seemed to be on track to become one of America’s greatest actors. That never quite came to pass — most likely because of his unshakeable identification with the camp/kitsch sci-fi TV series Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, in which he starred from 1964 to ’68 for producer Irwin (“Irwin the Terrible”) Allen. Despite that gig, which no doubt seemed like a good idea at the time, he remained an actor’s actor to the end of his days (a series of strokes took him off at 70 in 1984). In 1951 he still had fine performances ahead of him, especially the Fool in Fellini’s La Strada in 1954 and as Ishmael in John Huston’s Moby Dick two years later. As with Douglas, his work in Fourteen Hours is among his best. (Basehart’s performance is all the more impressive in light of what he dealt with during production. In May 1950, his wife of ten years, Stephanie Klein, was diagnosed with a brain tumor; she died on July 28 after surgery. Returning to work after her funeral, Basehart sprained an ankle. Then he contracted poison oak while cutting down a tree on the grounds of his Coldwater Canyon home.)

Fourteen Hours shot two weeks in Manhattan, with the Guaranty Trust Co. of New York at 23 Wall Street standing in for the fictitious Rodney Hotel. The original plan was to shoot the crowd scenes over Memorial Day (May 30, a Tuesday that year), but that proved impractical — especially when it was found that a wider ledge had to be added to the building’s facade to accommodate the stuntman doubling for Basehart. Then it was seven weeks back at the Fox studio, where a duplicate of the fifteenth floor, inside and out, was built on Stage 8. Studio records estimate that Basehart spent 300 hours standing on that replica ledge, which integrates seamlessly with the location footage of his stunt double actually fifteen stories up (that brave man is identified by Wikipedia — if we can believe Wikipedia — as one Richard Lacovara).

In the final analysis, I think, Henry Hathaway proved to be much better suited to the picture than the estimable Howard Hawks would have been. Fourteen Hours is among Hathaway’s finest work — one of his least actionful, but one of his most suspenseful. He and Paxton tighten the suspense steadily as the movie progresses, and Hathaway draws understated performances from the large ensemble. And that cast is an unusually strong one. Grace Kelly, Ossie Davis and Joyce Van Patten weren’t the only ones who were going places; among the future “names” in the cast are John Cassavetes, Richard Beymer, David Burns, Brad Dexter, John Randolph, Brian Keith (Robert Keith’s son), and Janice Rule — though you’ll have to look pretty fast to spot some of them. As a suspense drama, a psychological study, a comment on crowd psychology, and a wry critique of self-serving news media (as pungent today as it was in 1951), Fourteen Hours is one of the best movies of the 1950s.

EPILOGUE: Spoilers ahead — proceed at your own risk!

At the end of Fourteen Hours Robert Cosick is finally brought in through the window to safety — you’ll have to see the movie to find out exactly how that comes about. Unfortunately, the day didn’t end as happily for John William Warde. At 10:30 p.m. that night, John said to Officer Glasco, “I’ve made up my mind.” Glasco took this as an optimistic sign that John had decided to come in; at least that’s how he chose to read it. “That’s the way to talk,” he said. About that time, a childhood friend of John’s arrived in room 1714, and he relieved Glasco at the window talking to John.

At the end of Fourteen Hours Robert Cosick is finally brought in through the window to safety — you’ll have to see the movie to find out exactly how that comes about. Unfortunately, the day didn’t end as happily for John William Warde. At 10:30 p.m. that night, John said to Officer Glasco, “I’ve made up my mind.” Glasco took this as an optimistic sign that John had decided to come in; at least that’s how he chose to read it. “That’s the way to talk,” he said. About that time, a childhood friend of John’s arrived in room 1714, and he relieved Glasco at the window talking to John.

Joel Sayre doesn’t identify the friend or say what he and John talked about. But at 10:38, after twelve hours — not fourteen — Glasco, sitting on the bed rubbing his tired legs, heard a roar from the crowd below: “There he goes!” Glasco burst into tears.

If you care to look for them, there are pictures of John falling, hitting the hotel’s marquee, lying like a bloody rag doll where he fell, and being almost literally scraped off the sidewalk into an ambulance. The pictures are out there, and they’re pretty grisly. New York’s news photographers were diligent that night; they didn’t want to miss something like that.

In the original version of Fourteen Hours the same thing (more or less) was supposed to happen to Robert Cosick. (It was probably the suicide angle that made Howard Hawks turn down the job.) In a series of oral history interviews with Polly Platt late in his life, Hathaway told the following story:

“The protagonist, played by Richard Basehart, was a weakling, and in my original version, he did commit suicide. But we previewed the picture the very day [Fox president] Spyros Skouras’ daughter actually jumped from a window. He wanted the picture burned. Six months later, Darryl ordered a happy ending and I felt the picture messed up…”

This story found its way, in almost exactly those words, into both Harold N. Pomaineville’s biography of Hathaway and Michael Troyan’s history of 20th Century Fox, and I hate to rain on another juicy Hollywood story, but the chronology doesn’t fit. Fourteen Hours began location shooting in Manhattan in June 1950, delayed from the Memorial Day start by the dressing of the bank building. Even if they started on June 1, the company would have resumed shooting at the Fox studio no earlier than June 16. Seven weeks on Stage 8 takes them to August 4 at the earliest.

Dionysia Colleen Skouras, age 24, leapt to her death from the roof of the Fox West Coast Building in Los Angeles on July 17. Obviously, Hathaway’s memory was playing him false. Fourteen Hours couldn’t have been ready to preview by then; it still had three weeks to shoot.

But here’s what does make sense. Midway through shooting, Ms. Skouras makes her sad exit. Maybe her father wants the picture shelved, maybe he doesn’t; in any case, Darryl Zanuck realizes he’s got an awfully delicate situation on his hands. He calls in John Paxton and orders a rewrite in which Robert Cosick survives. Hathaway balks; he wants to stick with the downbeat ending. Maybe Zanuck tells him that the only alternative is to shelve the picture, maybe he doesn’t. In any case, the compromise they reach is to shoot both endings.

Life Magazine (March 12, 1951) confirms that both endings were indeed shot, and the IMDb claims that “[s]ome original prints show the two different endings one right after the other.” Personally, I’ve never seen that other ending, and it’s not included among the extras on the DVD, so my guess is that it hasn’t survived. But it’s quite possible that when the picture was previewed — say, sometime in late August or early September — the preview audience saw both endings and were allowed to express their preference. Or there could have been two previews with one ending apiece, just to see which one went over better. Maybe Spyros Skouras chimed in, maybe he didn’t. In any case, Zanuck made the executive decision to go with the upbeat ending. Then, out of consideration for Skouras’s grief, he delayed the picture’s release until February (in L.A.) and March (New York and Great Britain).

Of course, all this is pure speculation — aside from the fact that Dionysia Skouras clearly didn’t die on the day of any preview. A search of the Fox archives might clear up what actually happened, but that’s a chore for another day. For the rest of his life, Hathaway preferred the ending where Robert jumps to his death, believing that Zanuck’s ending “messed up” the picture — and that’s his privilege.

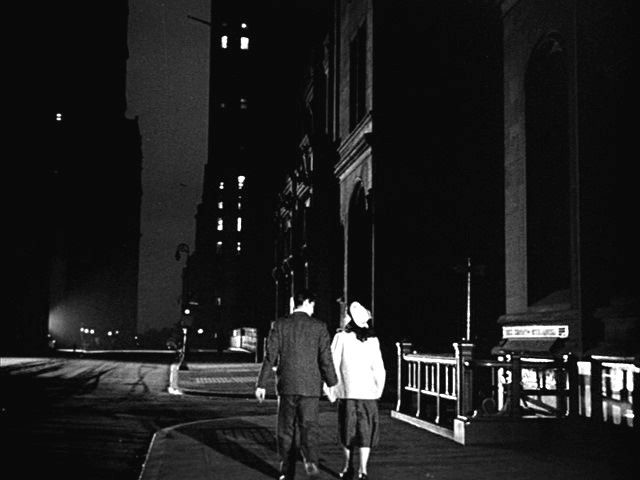

But Hathaway was wrong. As Alfred Hitchcock learned with the boy carrying the briefcase bomb in Sabotage (1936), you can’t build up suspense like that, get an audience all wound up, only to end with “…and then he died.” Not when people have invested so much time in hoping things will work out. Not to mention that the subplots with Grace Kelly and James Warren giving marriage another go, and Debra Paget and Jeffrey Hunter strolling away in the glow of young love in bloom, would turn to ashes in the mouth if they had to walk past Robert Cosick lying on the sidewalk in a puddle of blood.

Fourteen Hours‘s multiple stories are resolved with Dickensian neatness; even that cabbie with his tasteless betting pool finally grows an uneasy conscience. Zanuck — or that preview audience — was right; the ending is completely satisfying as it is. To hell with “real life”.

And one last thing. I promised an explanation for why Joel Sayre’s title, “The Man on the Ledge”, was changed to Fourteen Hours. This was done at the request of John Warde’s mother. Sayre’s 1949 article had reopened an 11-year-old wound and put her son’s last day back in the public eye; she wanted to distance the picture from him (and, perhaps, herself from the screeching harpy played by Agnes Moorehead). Even so, when a 60-minute version was produced in 1955 for the 20th Century Fox Hour TV series (with Cameron Mitchell and William Gargan replacing Basehart and Douglas), the title was once again “The Man on the Ledge”.