Cinevent 51 — Day 3

Saturday’s Animation Program this year was composed entirely of titles that had never been seen at Cinevent before, some of them quite rare. There were ten altogether, as always lovingly curated and annotated by Stewart McKissick. All were choice, but I’ll single out just five of my own favorites, illustrated here (with some YouTube links so you can pop over and watch them if you’re of a mind to). Clockwise from top left:

Saturday’s Animation Program this year was composed entirely of titles that had never been seen at Cinevent before, some of them quite rare. There were ten altogether, as always lovingly curated and annotated by Stewart McKissick. All were choice, but I’ll single out just five of my own favorites, illustrated here (with some YouTube links so you can pop over and watch them if you’re of a mind to). Clockwise from top left:

Mask-A-Raid (1931), an early Betty Boop — in fact, one of the first where she’s an actual human being rather than a weirdly sexy dog. Betty is the queen of a masquerade ball, and the proceedings are marked by the wiggy surrealism that was always Max and Dave Fleischer’s stock in trade. (If you do check it out on YouTube, note Betty’s entrance accompanied by identical-twin Mickey Mouses, both of them cut down to size and forced to carry Betty’s train. Max, Dave, you devils!)

The Hot Choc-Late Soldiers (1934). This one wasn’t a theatrical short, but a sequence produced by Walt Disney (and animated by Fred Moore) for MGM to include as a Technicolor sequence in Hollywood Party, a studio revue hung on a flimsy plot about Jimmy Durante inviting his movie star pals (including Mickey Mouse) to a soiree. Set to a song by Arthur Freed and Nacio Herb Brown, the cartoon portrays a war of confections, chocolate soldiers vs. gingerbread men. The pic here shows the cocoa army, battered but unbowed, marching home in triumph. The sequence is fun, with a look and style foreshadowing the next year’s The Cookie Carnival, one of my favorite Silly Symphonies. (Interesting side note: Eleven years later, when MGM wanted to borrow Mickey for a tap dance with Gene Kelly in Anchors Aweigh, Walt said no.)

Somewhere in Dreamland (1936). Two dirt-poor urchins dream themselves cavorting in the kind of country Disney’s chocolate soldiers come from — then wake up to find it’s all come true. This was the first Fleischer “Color Classic” to be made in three-strip Technicolor; before this Disney had exclusive use of the process and the Fleischers made do with Cinecolor or two-color Tech. Cinevent’s print wasn’t Technicolor, but it looked mighty nice; the YouTube post is almost as good.

Tulips Shall Grow (1942). In 22 years attending Cinevent, I’ve never seen one of producer George Pal’s 1940s Puppetoons presented there — understandably, since good prints of them are hard too find. What prints there are are usually unstable Eastmans struck for TV in the 1950s, now badly faded and beet-red travesties (hence no link for this one — that’s all YouTube has too). Tulips Shall Grow was one of the Hungarian-born Pal’s best and most heartfelt shorts. He had worked briefly in the Netherlands after fleeing the Third Reich; two years later, safely ensconced in Hollywood, he made this allegory of an idyllic Dutch countryside of windmills, tulips and young lovers in wooden shoes, ravaged by the “Screwball” (i.e., “Nazi”) Army. Again, Cinevent’s print wasn’t Technicolor, but it was gorgeous. (Another side note: This makes four straight years that George Pal has been a presence on Cinevent Saturday. In 2016 it was Houdini [’53]; in 2017, When Worlds Collide [’52]; and in 2018, The War of the Worlds [’53].)

Hullaba-Lulu (1944). Little Lulu (based on the popular single-panel cartoon by “Marge” that had been running in The Saturday Evening Post since 1935) was one of the series produced by Paramount after ousting the Fleischer brothers from their own animation studio. Like the Puppetoons, this series was all over TV in the 1950s but has all but vanished since then. In this one Lulu innocently creates havoc when the circus comes to town. I hadn’t seen this one in over 50 years, but I could still sing that unforgettable intro, the all-time-best-ever cartoon theme song.

After the cartoons — just like a Saturday Kiddie Matinee of my childhood — it was three more chapters of Hawk of the Wilderness. Then the Saturday Matinee mold was broken by a silent feature, 13 Washington Square (1928). Based on a popular 1915 Broadway play, it starred Alice Joyce as a snooty rich dame out to break up her son’s romance before he marries “beneath his station”. Going incognito while everybody thinks she’s sailing to Europe, she falls in with a smooth art thief (Jean Hersholt) who’s plotting to burglarize her Washington Square mansion while she’s supposedly out of the country. Everybody winds up running around the house just missing each other — the thief to rob the place, the mother to stop him, the son and his sweetheart (George J. Lewis, Helen Foster) to pack his clothes and elope. It sounds like a good old-fashioned door-slamming farce, and maybe that’s what it was on stage, but Melville Brown’s stodgy direction kept things from really taking off. Still, it was amusing (partly due to Zasu Pitts as Joyce’s maid), and love did triumph in the end.

After the cartoons — just like a Saturday Kiddie Matinee of my childhood — it was three more chapters of Hawk of the Wilderness. Then the Saturday Matinee mold was broken by a silent feature, 13 Washington Square (1928). Based on a popular 1915 Broadway play, it starred Alice Joyce as a snooty rich dame out to break up her son’s romance before he marries “beneath his station”. Going incognito while everybody thinks she’s sailing to Europe, she falls in with a smooth art thief (Jean Hersholt) who’s plotting to burglarize her Washington Square mansion while she’s supposedly out of the country. Everybody winds up running around the house just missing each other — the thief to rob the place, the mother to stop him, the son and his sweetheart (George J. Lewis, Helen Foster) to pack his clothes and elope. It sounds like a good old-fashioned door-slamming farce, and maybe that’s what it was on stage, but Melville Brown’s stodgy direction kept things from really taking off. Still, it was amusing (partly due to Zasu Pitts as Joyce’s maid), and love did triumph in the end.

After lunch it was the return of a longtime favorite feature at Cinevent, a program of Charley Chase comedy shorts. This year’s entries were You Said a Hatful (1934), The Count Takes a Count (’36), and Calling All Doctors (’37), all quite funny. Welcome back, Charley; we missed you last year.

After lunch it was the return of a longtime favorite feature at Cinevent, a program of Charley Chase comedy shorts. This year’s entries were You Said a Hatful (1934), The Count Takes a Count (’36), and Calling All Doctors (’37), all quite funny. Welcome back, Charley; we missed you last year.

Then came the event that tied in with the Wednesday night Wexler Center program of two Audrey Hepburn pictures — author Robert Matzen gave a presentation on his latest book, Dutch Girl: Audrey Hepburn and World War II. Already a bestseller on Amazon in three different categories (World War II History, World War II Biography, and Entertainment Biography), the book recounts teenage Audrey’s experiences under the German occupation of the Netherlands. (Ironically, Audrey had been in school in England when the war broke out. She was called back for her own safety by her Dutch mother, who assumed that England would be invaded any day. Mom further assumed that Hitler would respect the Netherlands’ neutrality as Kaiser Whilhelm had done in World War I. It was the least of the delusions of which Mom was fated to be disabused.)

Robert Matzen introduced Dutch Girl as the third and final volume in what he termed his “Hollywood in World War II” trilogy, following Fireball: Carole Lombard and the Mystery of Flight 3 and Mission: Jimmy Stewart and the Fight for Europe. His presentation was informative and tantalizing, as he occasionally hinted at juicy details that he wouldn’t disclose — “For that you’ll have to read the book.” I picked up my own copy of Dutch Girl at one of Robert’s book signings; I’m reading it now and may well have more to say in a later post. For now I can certainly recommend my readers hop on the bestseller bandwagon and get the book for themselves. (By the way, a noted filmmaker who shall here remain nameless, but who knew and worked with Audrey late in her too-short life, has expressed a keen interest in filming Dutch Girl. I hope that comes to pass; it would mark the completion of the filmmaker’s own World War II trilogy.) (Oops! Make that a “quintilogy”; Dutch Girl would be the filmmaker’s fifth picture about the war.)

Just before the dinner break came one of the surprise highlights of the whole weekend — a surprise to me, anyhow. Not because I didn’t expect it to be good, but because it was so much better than I expected. This was The Marshal of Mesa City (1939), with George O’Brien as a former lawman who takes up the badge again in a new town — this because he takes a shine to a local schoolteacher (Virginia Vale, O’Brien’s leading lady in six of these B-westerns he made for RKO), while he also takes an instant dislike to the corrupt county sheriff (Leon Ames) who’s been forcing his attentions on the school marm.

Just before the dinner break came one of the surprise highlights of the whole weekend — a surprise to me, anyhow. Not because I didn’t expect it to be good, but because it was so much better than I expected. This was The Marshal of Mesa City (1939), with George O’Brien as a former lawman who takes up the badge again in a new town — this because he takes a shine to a local schoolteacher (Virginia Vale, O’Brien’s leading lady in six of these B-westerns he made for RKO), while he also takes an instant dislike to the corrupt county sheriff (Leon Ames) who’s been forcing his attentions on the school marm.

George O’Brien deserves to be remembered much better than he is. Starting out in Hollywood as a stuntman, he rose up the ladder to star in some of the biggest pictures of the silent era: John Ford’s The Iron Horse (1924), F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise (’27), Michael Curtiz’s Noah’s Ark (’29). The Iron Horse landed him a charter membership in Ford’s stock company, and he later played key roles in Fort Apache (’48), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (’49) and Cheyenne Autumn (’64). In between he was a top box-office draw in dozens of westerns, first at Fox, then RKO, and it’s easy to see why. He combined extreme good looks and physical prowess with likeability and an easygoing sense of humor. And oh yeah, he also served with distinction in the U.S. Navy during both World Wars.

In my limited experience of O’Brien’s westerns, The Marshal of Mesa City is easily the best, for a number of reasons — chief among them a movie-stealing performance by Henry Brandon as a gunslinger hired by Ames to kill O’Brien, but who switches sides when he decides he likes his intended victim better. Another plus was director David Howard (who helmed many of O’Brien’s pictures). He may have been a routine talent, but his climactic shot of O’Brien and Brandon striding into the thick smoke of the burning jail, guns blazing, for a showdown with Ames and his gang — that was worthy of John Ford or Henry Hathaway.

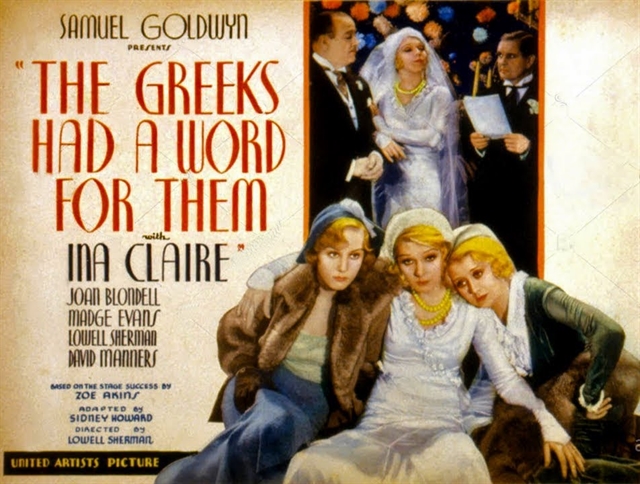

Richard Barrios introduced The Greeks Had a Word for Them (1932), a risqué Pre-Code comedy from producer Sam Goldwyn and director Lowell Sherman (who also co-starred as a lubricious concert pianist), based on Zoe Akins’s 1930 play. Ina Claire, Joan Blondell and Madge Evans were deliciously well-matched, romping through the story of gal-pals trolling for sugar daddies. The three-gold-diggers-on-the-prowl premise was already familiar, and it would become even more so by way of Warner Bros.’ Gold Diggers series and 20th Century Fox’s recycling its similar story from Three Blind Mice to Moon Over Miami to Three Little Girls in Blue to How to Marry a Millionaire, right down to 2011’s Monte Carlo with Selena Gomez (also from Fox, though the studio was much changed by then). That familiarity may account for why Goldwyn always counted The Greeks a disappointment and sold it off to some fly-by-nighters. Nevertheless, it holds up well today; the stars are sassy and the Goldwyn gloss is much in evidence.

Richard Barrios introduced The Greeks Had a Word for Them (1932), a risqué Pre-Code comedy from producer Sam Goldwyn and director Lowell Sherman (who also co-starred as a lubricious concert pianist), based on Zoe Akins’s 1930 play. Ina Claire, Joan Blondell and Madge Evans were deliciously well-matched, romping through the story of gal-pals trolling for sugar daddies. The three-gold-diggers-on-the-prowl premise was already familiar, and it would become even more so by way of Warner Bros.’ Gold Diggers series and 20th Century Fox’s recycling its similar story from Three Blind Mice to Moon Over Miami to Three Little Girls in Blue to How to Marry a Millionaire, right down to 2011’s Monte Carlo with Selena Gomez (also from Fox, though the studio was much changed by then). That familiarity may account for why Goldwyn always counted The Greeks a disappointment and sold it off to some fly-by-nighters. Nevertheless, it holds up well today; the stars are sassy and the Goldwyn gloss is much in evidence.

Conrad in Quest of His Youth (1920) was an appealing romantic dramedy (though the word hadn’t been coined yet) directed by Cecil B. DeMille’s big brother William, based on a 1903 bestseller by British novelist Leonard Merrick. Thomas Meighan starred as a disillusioned, middle-aged British Army officer jaded by service in India and seeking to regain the pleasures of his younger self. He learns, of course (20 years before Thomas Wolfe said it), that he can’t go home again. Then, even further disheartened, he falls in with a down-on-their-luck theatrical troupe, eventually learning that happiness is found in looking forward, not back.

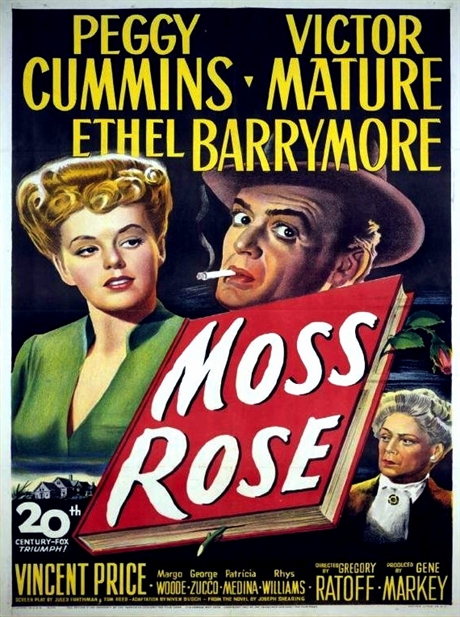

Moss Rose (1947) was a decent enough thriller that nevertheless left a sense that it should have been better. Based on a 1934 novel by the prolific Margaret Gabrielle Vere Long (writing as Joseph Shearing), the picture was evidently Darryl F. Zanick’s attempt to repeat the success of Fox’s earlier ventures into Victorian Gothic suspense, The Lodger (1944) and Hangover Square (1945). Indeed, the role of murder suspect Michael Drego was tailor-made for Lodger and Hangover Square star Laird Cregar — who might well have played it if he hadn’t crash-dieted himself to death in 1944. Instead, the role went to Victor Mature — a better actor than he often gets credit for, but, well, Victorian Gothic probably wasn’t part of his skill set.

Moss Rose (1947) was a decent enough thriller that nevertheless left a sense that it should have been better. Based on a 1934 novel by the prolific Margaret Gabrielle Vere Long (writing as Joseph Shearing), the picture was evidently Darryl F. Zanick’s attempt to repeat the success of Fox’s earlier ventures into Victorian Gothic suspense, The Lodger (1944) and Hangover Square (1945). Indeed, the role of murder suspect Michael Drego was tailor-made for Lodger and Hangover Square star Laird Cregar — who might well have played it if he hadn’t crash-dieted himself to death in 1944. Instead, the role went to Victor Mature — a better actor than he often gets credit for, but, well, Victorian Gothic probably wasn’t part of his skill set.

Then again, if the director had been John Brahm, whose talent for what Andrew Sarris called “mood-drenched melodrama” had made winners out of The Lodger and Hangover Square, Mature might have been able to get with the program. But the director was Gregory Ratoff, who divided his career between the director’s chair and as a character actor playing querulous mittel-European parvenus — and as a director, Ratoff made an excellent mittel-European parvenu.

Peggy Cummins, still licking her wounds over geting canned from Forever Amber, played a music-hall chorus girl investigating the murder of a friend who apparently got too close to the family secrets of Mature’s Drego and his mother Lady Margaret (Ethel Barrymore). Everyone on screen, including Vincent Price as a Scotland Yard detective and Patricia Medina as Mature’s fiancée, gave it their best shot. But the picture failed to find an audience. In a 1950 memo, Darryl Zanuck said it “was a catastrophe, for which I blame myself. Our picture was not as good as the original script and the casting was atrocious. The property lost $1,300,000 net…” Zanuck was too harsh; nothing about Moss Rose was “atrocious”. It was an interesting effort — but it was a bit of a misfire, shooting at a target where the studio had hit the bullseye twice before.

The day ended not with a bang but a whimper: Holy Wednesday (aka Snakes) (1974), produced in San Bernardino, Calif. on a shoestring for the drive-in circuit, it starred ’50s sci-fi stalwart Les Tremayne as an aged hermit siccing his herd of deadly serpents on his enemies. I didn’t stay. I watched about five minutes, enough to persuade me that this was ideal fodder for the robots on Mystery Science Theatre 3000, then I called it a day.

* * *

There was some important news announced on Saturday by Cinevent chair Michael Haynes (on the left in this picture, in case you need to be told) and Dealers’ Room coordinator Samantha Glasser (the one who isn’t Michael).

There was some important news announced on Saturday by Cinevent chair Michael Haynes (on the left in this picture, in case you need to be told) and Dealers’ Room coordinator Samantha Glasser (the one who isn’t Michael).

Cinevent will return for Memorial Day Weekend 2020, which will be Michael’s last turn in the driver’s seat. At that point he’ll pass the baton to Samantha, who will continue the tradition into 2021 and beyond with a new organization which she is putting together even as you read this — a group that will, no doubt, include a good percentage of the current Cinevent staff. Also at the end of the 2020 convention, the Cinevent name will be retired.

Why retire the name? Well, when Steven Haynes passed away in 2015, he was the last of Cinevent’s original founders, John Baker and John Stingley having gone on before him. Now that Michael Haynes and his mother Barbara are withdrawing from active participation, it’s their wish to take the name with them. I can certainly sympathize and agree with that — but it won’t be easy to come up with a name as clever, as evocative, as…well, as downright cool as that.

As for the new name, Samantha is soliciting suggestions. Submit yours to her at SamanthaKGlasser@gmail.com by June 30, 2019. It’s worth free admission in 2021 if your idea is chosen.