Crazy and Crazier, Part 2

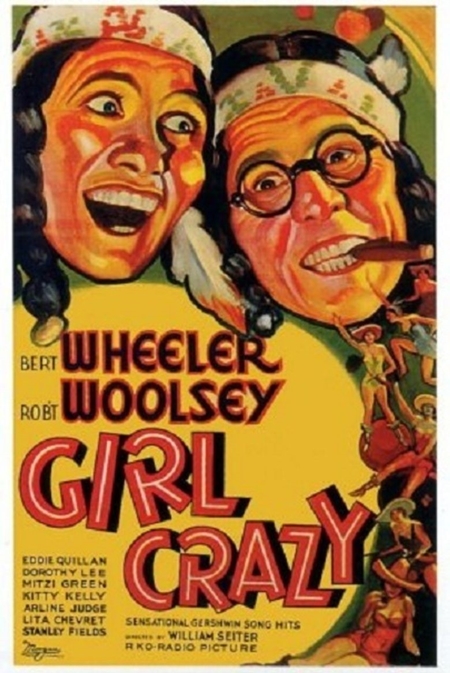

I have this fantasy in which I imagine that a scout from RKO Radio Pictures early in 1931 is told to go see Girl Crazy on Broadway and to report back about its potential as a movie. In his report, does he say, “The score is amazing; George and Ira Gershwin have written some songs that will be sung as long as singers sing”? Or “This Ethel Merman is dynamite; she electrifies an audience and she can put a song over like an artillery barrage”? Or “Ginger Rogers is a real charmer who has already shown that she photographs well; with care she could be groomed into a major star”? Does he say any of this? He does not. Instead, this brilliant showbiz oracle tells the front office, “This might make a good vehicle for Wheeler and Woolsey.”

I have this fantasy in which I imagine that a scout from RKO Radio Pictures early in 1931 is told to go see Girl Crazy on Broadway and to report back about its potential as a movie. In his report, does he say, “The score is amazing; George and Ira Gershwin have written some songs that will be sung as long as singers sing”? Or “This Ethel Merman is dynamite; she electrifies an audience and she can put a song over like an artillery barrage”? Or “Ginger Rogers is a real charmer who has already shown that she photographs well; with care she could be groomed into a major star”? Does he say any of this? He does not. Instead, this brilliant showbiz oracle tells the front office, “This might make a good vehicle for Wheeler and Woolsey.”

Bert Wheeler and Robert Woolsey — unlike, say, Laurel and Hardy, Abbott and Costello, or the Marx Brothers — are largely forgotten today, but they still have their fans among film buffs even now. So perhaps I should let you know right up front that Wheeler and Woolsey are my personal nominees for the worst comedy team in movie history. But no matter what I think, they were hugely popular in the 1930s. Their output alone shows that audiences could hardly get enough. The Marx Brothers, for example, made 13 pictures in their entire career, from 1929 to ’49. Wheeler and Woolsey made 22 features — plus one short of their own and guest appearances in five others — just between 1929 and ’37. And they only stopped then because of Woolsey’s failing health (he died of kidney failure at 50 in 1938).

Wheeler and Woolsey were never a team in the standard showbiz sense of the day, as Woolsey was careful to point out when the two split up (briefly) after the release of Girl Crazy in 1932: “I wish it understood that Wheeler and I never really formed a team at any time. He had his manager and attorney and I had mine.” Wheeler had started in vaudeville with an act that, in retrospect, sounds like a forerunner of Andy Kaufman’s schtick: he would come out on stage with a joke book and announce that he was going to read some jokes from it, then proceed to read one corny joke after another, in such a manner that the audience would wind up roaring with laughter. Woolsey, who stood just under five foot six, had started out as a jockey and exercise boy, but when he broke his leg in a fall from a horse his racing career was over. The horse, Pink Star, went on to win the Kentucky Derby in 1907; Woolsey went into show business.

Bringing the two together was Florenz Ziegfeld Jr.’s idea; he cast them as comic supports to Ethelind Terry and J. Harold Murray in his 1927 musical extravaganza Rio Rita. When RKO bought the movie rights to Rita in 1929, they replaced the stars with John Boles and Bebe Daniels, but they brought Wheeler and Woolsey west to recreate their stage roles. The dynamic of this duo was already firmly in place, and it would not vary in their following match-ups: wide-eyed naif Wheeler is bamboozled and manipulated by the fast-talking, cigar-chomping Woolsey. The two made such a hit in Rita that RKO teamed them up again (The Cuckoos) and again (Dixiana), over and over — a new picture, on average, every three months. (“They were pretty bad,” Wheeler later recalled, “but they all made money.”) Girl Crazy was their tenth, in two-and-a-half years.

Almost a third member of the (not really a) team was diminutive Dorothy Lee; she appeared in 16 of Wheeler and Woolsey’s pictures. A good physical match for Wheeler (he was five foot four, she five foot exactly), Lee served as a romantic partner for him, giving Wheeler (and the audience) a little relief from the obnoxious blowhard Woolsey. So it was in Girl Crazy, in which Wheeler took the role played on Broadway by Willie Howard (whose intransigence had killed the show before its time). The cabbie’s name was de-ethnicized from Gieber Goldfarb to Jimmy Deegan, the character was divested of the comic Yiddish persona that was Howard’s stock in trade, and Lee was brought in as Patsy, “the gal of the golden west”, to duet with Wheeler in one of only four musical numbers in the movie.

Almost a third member of the (not really a) team was diminutive Dorothy Lee; she appeared in 16 of Wheeler and Woolsey’s pictures. A good physical match for Wheeler (he was five foot four, she five foot exactly), Lee served as a romantic partner for him, giving Wheeler (and the audience) a little relief from the obnoxious blowhard Woolsey. So it was in Girl Crazy, in which Wheeler took the role played on Broadway by Willie Howard (whose intransigence had killed the show before its time). The cabbie’s name was de-ethnicized from Gieber Goldfarb to Jimmy Deegan, the character was divested of the comic Yiddish persona that was Howard’s stock in trade, and Lee was brought in as Patsy, “the gal of the golden west”, to duet with Wheeler in one of only four musical numbers in the movie.

Musicals, a novelty in the late ’20s, had worn out their welcome by 1932 and become a drug on the market; theater owners were known to reassure audiences in ads and posters that their current offering was “Not a Musical!” (The Big Revival over at Warner Bros. was still a year away.) In this atmosphere, no one at RKO was in a mood to look twice at the Gershwins’ songs in Girl Crazy. Instead, taking their cue from Willie Howard and William Kent having been the ones with star billing on Broadway, the studio jettisoned most of the score and refashioned the book — the weakest thing about the show — to suit their hot new team. So it is that in the movie, it isn’t Eddie Quillan’s Danny Churchill who takes a taxi from Manhattan to Arizona, it’s the gambler Slick (new surname: Foster) who hops into Jimmy Deegan’s cab for the trip out west. (The lady in the back seat with Woolsey is Kitty Kelly, playing what’s left of Ethel Merman’s role.) Two huge chunks of the picture’s modest 74-minute running time are eaten up by (1) Wheeler and Woolsey’s misadventures on the road to Arizona and (2) further misadventures later, when the action adjourns to Mexico.

Musicals, a novelty in the late ’20s, had worn out their welcome by 1932 and become a drug on the market; theater owners were known to reassure audiences in ads and posters that their current offering was “Not a Musical!” (The Big Revival over at Warner Bros. was still a year away.) In this atmosphere, no one at RKO was in a mood to look twice at the Gershwins’ songs in Girl Crazy. Instead, taking their cue from Willie Howard and William Kent having been the ones with star billing on Broadway, the studio jettisoned most of the score and refashioned the book — the weakest thing about the show — to suit their hot new team. So it is that in the movie, it isn’t Eddie Quillan’s Danny Churchill who takes a taxi from Manhattan to Arizona, it’s the gambler Slick (new surname: Foster) who hops into Jimmy Deegan’s cab for the trip out west. (The lady in the back seat with Woolsey is Kitty Kelly, playing what’s left of Ethel Merman’s role.) Two huge chunks of the picture’s modest 74-minute running time are eaten up by (1) Wheeler and Woolsey’s misadventures on the road to Arizona and (2) further misadventures later, when the action adjourns to Mexico.  As for those four songs, only three were from the show. The movie opens promisingly with an amusing, if abbreviated, rendition of “Bidin’ My Time”, with four singing cowboys moseyin’ along on the back of the same overburdened horse, while the camera moves through the Custerville cemetery from the grave of one luckless sheriff to the next, and the next.

As for those four songs, only three were from the show. The movie opens promisingly with an amusing, if abbreviated, rendition of “Bidin’ My Time”, with four singing cowboys moseyin’ along on the back of the same overburdened horse, while the camera moves through the Custerville cemetery from the grave of one luckless sheriff to the next, and the next. A few minutes later comes “You’ve Got What Gets Me” a new song by George and Ira written for the movie. (In point of fact, it wasn’t entirely new; it was a reworking of another song, “Your Eyes, Your Smile”, which had been cut from the Broadway production of Funny Face before it opened in 1927.) This is a light romantic duet between Wheeler and Dorothy Lee (already, as noted, a staple of their pictures together), followed by a sprightly tap dance in which they’re joined by little Mitzi Green as Wheeler’s pesky sister. Toward the end of her life, Dorothy Lee remembered Girl Crazy with bitter disgust as the movie where they photographed her behind a post (“I saw it once,” she said. “I couldn’t look at it again.”), and this frame from the dance shows she wasn’t being hypersensitive — you can just about make out her elbows (she’s dancing to the left of Wheeler). Why would anybody bother to stage a tap dance on a set dominated by an enormous vine-covered wishing well right in the middle of the floor (and seemingly taking up half of it)? It’s hard to comprehend — but then, the songs simply weren’t a priority.

A few minutes later comes “You’ve Got What Gets Me” a new song by George and Ira written for the movie. (In point of fact, it wasn’t entirely new; it was a reworking of another song, “Your Eyes, Your Smile”, which had been cut from the Broadway production of Funny Face before it opened in 1927.) This is a light romantic duet between Wheeler and Dorothy Lee (already, as noted, a staple of their pictures together), followed by a sprightly tap dance in which they’re joined by little Mitzi Green as Wheeler’s pesky sister. Toward the end of her life, Dorothy Lee remembered Girl Crazy with bitter disgust as the movie where they photographed her behind a post (“I saw it once,” she said. “I couldn’t look at it again.”), and this frame from the dance shows she wasn’t being hypersensitive — you can just about make out her elbows (she’s dancing to the left of Wheeler). Why would anybody bother to stage a tap dance on a set dominated by an enormous vine-covered wishing well right in the middle of the floor (and seemingly taking up half of it)? It’s hard to comprehend — but then, the songs simply weren’t a priority.  But, with all due sympathy to Ms. Lee, that’s not the worst. The absolute nadir of RKO’s Girl Crazy — lower than any of Wheeler and Woolsey’s comedy, already too low by half — comes with the disgraceful treatment accorded “But Not for Me”. What on Broadway had been a wistful solo of lost love by Ginger Rogers was revamped as a trio for Eddie Quillan as Danny, Arline Judge as Molly, and Mitzi Green trying to patch things up between them. Ira’s lyric was twisted around to say the exact opposite of what he wrote (“Beatrice Fairfax, don’t you dare/Ever tell me he won’t care…”), and George’s tempo was sped up until the song sounded like the merry-go-round gone wild in Strangers on a Train. Quillan and Judge were hardly singers (which may explain the breakneck tempo, always easier for non-singers to handle), and they rush through the song as if they have to be someplace; Quillan darts off-camera before the music even tinkles to a stop. The song comes off like a playground argument between two petulant kids. It’s followed by a reprise in which Green tries to cheer Judge up by using the song to do impressions (and pretty good ones, too) of Bing Crosby, Roscoe Ates, George Arliss and Edna May Oliver. This plays oddly today, especially with audiences who never heard of Ates, Arliss or Oliver, but at least it had a counterpart in the original show: Willie Howard was famous for his impressions, and the book incorporated them by having the cabbie try to cheer Ginger Rogers’ Molly with a reprise a la Rudy Vallee and Maurice Chevalier — but only after Ginger had already given the song its full soulful due. This movie never bothers to do that.

But, with all due sympathy to Ms. Lee, that’s not the worst. The absolute nadir of RKO’s Girl Crazy — lower than any of Wheeler and Woolsey’s comedy, already too low by half — comes with the disgraceful treatment accorded “But Not for Me”. What on Broadway had been a wistful solo of lost love by Ginger Rogers was revamped as a trio for Eddie Quillan as Danny, Arline Judge as Molly, and Mitzi Green trying to patch things up between them. Ira’s lyric was twisted around to say the exact opposite of what he wrote (“Beatrice Fairfax, don’t you dare/Ever tell me he won’t care…”), and George’s tempo was sped up until the song sounded like the merry-go-round gone wild in Strangers on a Train. Quillan and Judge were hardly singers (which may explain the breakneck tempo, always easier for non-singers to handle), and they rush through the song as if they have to be someplace; Quillan darts off-camera before the music even tinkles to a stop. The song comes off like a playground argument between two petulant kids. It’s followed by a reprise in which Green tries to cheer Judge up by using the song to do impressions (and pretty good ones, too) of Bing Crosby, Roscoe Ates, George Arliss and Edna May Oliver. This plays oddly today, especially with audiences who never heard of Ates, Arliss or Oliver, but at least it had a counterpart in the original show: Willie Howard was famous for his impressions, and the book incorporated them by having the cabbie try to cheer Ginger Rogers’ Molly with a reprise a la Rudy Vallee and Maurice Chevalier — but only after Ginger had already given the song its full soulful due. This movie never bothers to do that.As it happened, the final cut wasn’t final after all. Girl Crazy had begun under the regime of RKO studio chief William LeBaron; by the time it finished shooting, LeBaron was gone (though he retained screen credit), replaced by David O. Selznick. The picture’s first preview in Glendale was not well received, and Selznick ordered retakes — enough to add another $200,000 to the $300,000 already spent. Exactly what was reshot isn’t clear, but the figures alone suggest a full two-thirds of the picture as it stood. In any case, director William A. Seiter wasn’t available, so the retakes were directed (without credit) by Norman Taurog.

And this is where we run into the mystery of the “I Got Rhythm” number. Selznick may have ordered the reshooting of the song, in whole or in part (the paper trail isn’t clear), and the sequence may have been staged and directed by Busby Berkeley, who was already at RKO to stage the native dances for Bird of Paradise. Berkeley himself never said anything about it, but that doesn’t necessarily mean anything — after all, Dorothy Lee didn’t like to talk about Girl Crazy either, and she’s on screen. On the strength of what we can see, my own opinion is that “I Got Rhythm” is Busby Berkeley’s work lock, stock and barrel. Later, after Berkeley had made his name over at Warner Bros., dance directors at other studios would prove that Berkeley’s style was easier to recognize than to imitate, and “I Got Rhythm” is his style to a “T”; there are images and motifs that would reappear in some of his most famous routines at Warners. Besides, this number is by far the most elaborate and complex sequence in the entire picture, and could easily account for much of that extra 200 grand. Until someone shows me conclusive evidence to the contrary, I’ll continue to believe that “I Got Rhythm” is Busby Berkeley at work. Whatever the case, Berkeley, like Taurog, got no screen credit for the retakes Selznick had ordered.

The retakes didn’t help, and may have hurt; Girl Crazy failed to turn a profit. After Selznick’s tinkering, it had cost nearly twice as much as the typical Wheeler and Woolsey picture (and almost as much as RKO’s special-effects extravaganza King Kong); it never had a chance. It probably never had an artistic chance either; coming at exactly the moment when even mentioning a musical around Hollywood was in bad taste, Girl Crazy was a movie that couldn’t decide what it wanted to be. It waffled a little, then came down on what looked like the safe side as a straight cornball comedy. RKO decided to play up the one feature of the show (the book) that Broadway audiences had tolerated only for the sake of what came with it, leaving just a skeleton crew of songs that were either inconsequential, mishandled, or too little too late.

The following year would come the game-changer: Warner Bros. (and Busby Berkeley) with the spectacular hat trick of 42nd Street, Gold Diggers of 1933 and Footlight Parade to put musicals back in vogue again, where they would remain for decades — even Poverty Row studios like Republic, Monogram and PRC would regularly try their hands at them. But all that came too late to help RKO’s Girl Crazy. It was born before its time; the studio didn’t appreciate the property it had, and didn’t have the wit, confidence or foresight to do what should have been done with it.

The following year would come the game-changer: Warner Bros. (and Busby Berkeley) with the spectacular hat trick of 42nd Street, Gold Diggers of 1933 and Footlight Parade to put musicals back in vogue again, where they would remain for decades — even Poverty Row studios like Republic, Monogram and PRC would regularly try their hands at them. But all that came too late to help RKO’s Girl Crazy. It was born before its time; the studio didn’t appreciate the property it had, and didn’t have the wit, confidence or foresight to do what should have been done with it.

All was not lost, however. Better times were coming for Girl Crazy, though it would take another 11 years. Oddly enough, Norman Taurog and Busby Berkeley would be back. And this time they’d get screen credit.

Jim, sorry to have bounced around some in my attempt to catch up with your awesome blog post about GIRL CRAZY, but I finally caught up with Part 2. I can readily understand why it didn't set the box office on fire, but I enjoyed your detailed post explaining what went wrong. 🙂 You deserve some kind of reward for the research alone! Great job!

Kevin, I agree about Dorothy Lee: a real cutie. Not well served in Girl Crazy, though; I had trouble finding a good frame-cap for her because they shot so much of her role with her back to the camera.

I've never seen this one. Despite what you wrote, Jim, I'm still curious about it and will try to catch it on its next appearance on TCM.

I'm of mixed minds on W&W. I'm not particularly fond of them, but I like their movies, mainly because I like 1930s comedies.

So I watch, and enjoy, titles like "Kentucky Kernels" and (my favorite of those I've seen) "Hips, Hips Hooray." I guess you can I say I like their movies in spite of them, not because of them.

Besides, Dorothy Lee was a real cutie, and a very appealing screen presence.

Wheeler and Woolsey good names

to remember not to remember.

An appropriate response, CW, but I hope you at least stuck with it through "I Got Rhythm". "You've Got What Gets Me" also perks things up a little — except for that stupid wishing well. It's like a dead elephant on the set.

I saw some of the movie once. I wasn't expecting much, but the opening number got my hopes up. My hopes were then dashed, although I am a fan of Mitzi Green. (One of my sisters is a major Wheeler & Woolsey fan. Sometimes they work for me and sometimes they don't.)

I didn't have the guts to stick with the picture all the way through. it made me sad.