Cinevent 2017 – No. 49 and Counting, Part 4

Day 4 – Sunday

There were a couple of pictures on the last day of Cinevent that I wish I could report on, but alas, I didn’t see them. First, and most promising, was Carmen (1918), one of several silent version of Bizet’s opera — or, more accurately, of Prosper Mérimée’s original novella, which by 1915 was safely in the public domain, whereas the opera was still under copyright. No matter, it was the popularity of the opera that led to duelling Carmens in 1915, one directed by Cecil B. DeMille with Geraldine Farrar for Paramount, the other by Raoul Walsh with Theda Bara over at Fox. And it led to this German version, directed by Ernst Lubitsch and starring Pola Negri, released in December 1918, just a month after the Armistice that ended World War I. It didn’t find a Stateside distributor until 1921, when First National released it as Gypsy Blood (the title Carmen being deemed too easily confused with its predecessors). The picture was successful enough (“This Negri is amazing,” said Variety) to bring both Negri and director Lubitsch to Hollywood with American contracts. Lubitsch prospered, Negri not so much; her brash impulsiveness wound up annoying and alienating people, eventually sending her back to Germany until the rise of Hitler drove her once again to the U.S. Her career never really recovered. Anyhow, that was the picture that led off Day 4, and I’m sorry I missed it. God only knows when I’ll get another chance. (A complete German version has recently surfaced, without the cuts First National imposed for U.S. release, but hasn’t become widely available; Cinevent showed the First National edition.)

There were a couple of pictures on the last day of Cinevent that I wish I could report on, but alas, I didn’t see them. First, and most promising, was Carmen (1918), one of several silent version of Bizet’s opera — or, more accurately, of Prosper Mérimée’s original novella, which by 1915 was safely in the public domain, whereas the opera was still under copyright. No matter, it was the popularity of the opera that led to duelling Carmens in 1915, one directed by Cecil B. DeMille with Geraldine Farrar for Paramount, the other by Raoul Walsh with Theda Bara over at Fox. And it led to this German version, directed by Ernst Lubitsch and starring Pola Negri, released in December 1918, just a month after the Armistice that ended World War I. It didn’t find a Stateside distributor until 1921, when First National released it as Gypsy Blood (the title Carmen being deemed too easily confused with its predecessors). The picture was successful enough (“This Negri is amazing,” said Variety) to bring both Negri and director Lubitsch to Hollywood with American contracts. Lubitsch prospered, Negri not so much; her brash impulsiveness wound up annoying and alienating people, eventually sending her back to Germany until the rise of Hitler drove her once again to the U.S. Her career never really recovered. Anyhow, that was the picture that led off Day 4, and I’m sorry I missed it. God only knows when I’ll get another chance. (A complete German version has recently surfaced, without the cuts First National imposed for U.S. release, but hasn’t become widely available; Cinevent showed the First National edition.)

The other one I’m sorry I missed was The Trial of Vivienne Ware (1932), an early example of entertainment synergy — a movie based on a popular radio serial, and one that (on radio) employed a sort of primitive audience participation, with listeners making story suggestions even as the program was playing on their radio sets. The movie, which has Joan Bennett in the title role of a socialite on trial for killing her two-timing fiancé and defended by ex-beau Donald Cook, is famous for its breakneck pace (it runs only 56 minutes) and dizzy editing, with whip-pans marking transitions from scene to scene.

One that I did see, the second feature of the morning, was The Old Corral (1936), an early Republic western with singing star Gene Autry — and all I can say is I wish it had been as good as this poster makes it look. Republic — only a year old in 1936 but already releasing its 49th picture — hadn’t yet mastered the craft of cranking out low-budget westerns, and Autry wasn’t yet as comfortable on camera as he would eventually become. The picture is mainly interesting for two things: (1) the presence of the singing group Sons of the Pioneers, particularly a young man born Leonard Slye but going by the name of Dick Weston; he would eventually be known as Roy Rogers and would outclass Gene Autry on every level, even to the extent of doing some of his own stunts (Autry, in this one, is only too obviously doubled every time he sets down his guitar); and (2) Autry’s leading lady, a rather dowdy-looking miss named Hope Manning; later, in the 1940s, she would get a glamourous blonde makeover and a name change at Warner Bros. As Irene Manning, she would make her modest mark in such movies as Yankee Doodle Dandy (’42), The Desert Song (’43) and The Doughgirls (’44) before transitioning to television and retiring from showbiz in the mid-’50s. Comparing her here with her later work is a dramatic illustration of how the resources of a major studio could work wonders for a performer.

The highlight of the day for me was the penultimate screening of the entire weekend: The Magic Box (1951), the biography of William Friese-Greene, a controversial figure in early film history (either neglected pioneer or dillettante and nuisance, depending on your viewpoint). And here I’ll hand you over to the notes that I contributed to this year’s Cinevent program booklet (slightly expanded here):

The highlight of the day for me was the penultimate screening of the entire weekend: The Magic Box (1951), the biography of William Friese-Greene, a controversial figure in early film history (either neglected pioneer or dillettante and nuisance, depending on your viewpoint). And here I’ll hand you over to the notes that I contributed to this year’s Cinevent program booklet (slightly expanded here):

The exact contribution of William Friese-Greene to motion picture history remains a subject of controversy to this day. Born William Green in 1855 (later hyphenating his name with that of his first wife, Helena Friese, and adding the final “e” for good measure), he was an English portrait photographer who was bitten by the moving picture bug sometime in the mid-1880s. A tireless tinkerer and experimenter with a terrible head for business, he took out quite a number of patents, at least on paper, but always seemed to be behind the curve when it came to actually developing a movie camera of his own. The first film historian, Terry Ramsaye, dismissed Friese-Greene as a “personality of more interest than importance” in his landmark 1926 history A Million and One Nights: A History of the Motion Picture Through 1925. When The Magic Box, the British film industry’s reverent biopic of Friese-Greene, appeared a quarter-century later, Ramsaye was still around, and he didn’t hesitate to double down in the pages of Films in Review (Aug.-Sep. ’51), reiterating that “Friese-Greene was not an important figure in the history of the cinema.”

Still, the man has had his defenders, including Anglo-Canadian critic Gerald Pratley (who engaged in a point/counterpoint duel with Ramsaye in that same issue of FIR), and biographer Ray Allister, whose 1948 book Friese-Greene; Close-Up of an Inventor served as the basis for The Magic Box.

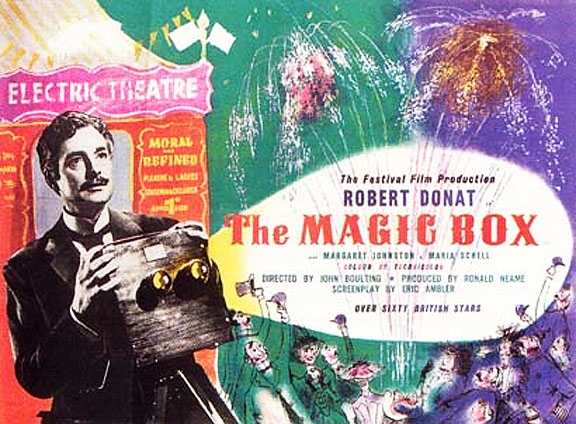

The Magic Box was part of the British film industry’s contribution to the Festival of Britain (hence the designation “The Festival Film Production” on the lobby card above). This was a vast array of exhibits and scientific and cultural events during the summer of 1951, ostensibly commemorating the centennial of the Crystal Palace Exposition of 1851, but really aimed at bucking up British morale and self-confidence after the devastation of World War II, and pointing the way to a brighter and more prosperous future. Part of the celebration included memorializing the British Empire’s glittering past, and what better way to do that than by a tribute to Friese-Greene, whom Allister extolled as the shamefully forgotten “true inventor” of motion pictures?

Needless to say, Eric Ambler’s script for The Magic Box followed Allister’s line faithfully, albeit with liberal doses of fiction, and studiously avoiding any specific claims as to exactly when Friese-Greene accomplished this feat. Also, Ambler tactfully passed over some inconvenient events in Friese-Greene’s life – for example, a brief stint in prison in 1891 for borrowing money illegally while still in undischarged bankruptcy; and a trip to America in the early 1910s to testify against the Edison Patents Trust, where he was found so unreliable, and so bereft of documents to back up his claims, that the independent producers didn’t dare put him on the stand. On the other hand, Ambler and director John Boulting faithfully reproduced Friese-Greene’s sad end: Attending a meeting of cinema distributors in London in 1921, he rose to speak, but was rambling, incoherent and barely audible, and had to be gently escorted back to his seat. He may have already been suffering his final medical event – heart attack, stroke, or cerebral hemorrhage – because just a few minutes later he fell over dead.

Whatever The Magic Box’s value as history, it’s a wonderful piece of entertainment. It draws a vivid picture of Victorian and Edwardian England, lusciously photographed by Jack Cardiff in that peerless British Technicolor (the print we’re showing isn’t IB Tech, alas, but we defy you to tell the difference).

And what a cast! Given the circumstances – cinema history, Festival of Britain and all that – working on this picture was practically a patriotic duty, and virtually the entire British acting profession showed up to do their bit. In fact, it’s easier to name people who aren’t in it than those who are: don’t look for Alec Guinness, John Mills, Noël Coward, Alastair Sim, John Gielgud, Charles Laughton, Ralph Richardson, Edith Evans, Rex Harrison, Joan Greenwood, James Mason, or Robert Newton. Otherwise, you name ’em, they’re probably here somewhere, in some cases without uttering a word.

And what a cast! Given the circumstances – cinema history, Festival of Britain and all that – working on this picture was practically a patriotic duty, and virtually the entire British acting profession showed up to do their bit. In fact, it’s easier to name people who aren’t in it than those who are: don’t look for Alec Guinness, John Mills, Noël Coward, Alastair Sim, John Gielgud, Charles Laughton, Ralph Richardson, Edith Evans, Rex Harrison, Joan Greenwood, James Mason, or Robert Newton. Otherwise, you name ’em, they’re probably here somewhere, in some cases without uttering a word.

One such cameo is contributed by Laurence Olivier in what has been recognized, in 1951 and ever since, as the best scene in the picture. Olivier plays a London policeman whom Friese-Greene drags off the street into his laboratory in the dead of night to witness his invention. As the bemused officer stares at the flickering image on Friese-Greene’s improvised screen, Olivier’s face shows what nobody living today — and precious few even in 1951 — can imagine: the absolutely gobsmacking amazement of seeing a photograph actually move right before his startled eyes. When the demonstration is over, the bobbie is still speechless; all he can do is stammer, “You must be a very happy man, Mr. Friese-Greene.” The scene is straight out of Ray Allister’s fanciful biography, and it’s almost certainly apocryphal. Friese-Greene spent years trying to prove his claim; why did he never find that copper to back him up? Nevertheless, the scene encapsulates the primal power of movies; at that moment, the title The Magic Box makes perfect sense.

Front and center in this once-in-a-lifetime cast, playing Friese-Greene, is the wonderful Robert Donat, whose fragile health and preference for the stage kept him from making as many movies as most of us would like. The Magic Box was in fact nearly his last appearance on screen – he would make only two more in the seven years left to him, before his chronic asthma and a brain tumor carried him off at age 53 – and it may be his last great performance. As Friese-Greene, he is perfectly cast: the physical resemblance is reasonably close, but the clincher is that amazing, melodic voice of his – perfectly expressive of this dreamy, unworldly character, the indefatigable experimenter who lets things like food and shelter for his family suffer in the face of his obsession with recording the moving image, and who, according to his second wife (as quoted in the movie), “wasn’t meant to have to worry about other people.”

Variety’s “Myro” reviewed The Magic Box on Sept. 26, 1951 during the waning days of the Festival of Britain, mentioning (of course) its “Who’s Who” cast and calling it “a standout contribution by the film industry here” to the Festival. It was another year before the picture crossed the Pond to New York, where the Times’ Bosley Crowther called it “as pretty a period piece as any you’ll see, full of the most exquisite little vignettes of Victorian England and Victorian ways and some highly fascinating indications of early experiments with film.” Meanwhile, across town at The New Yorker, John McCarten yawned, “It’s a sentimental affair,” but allowed, “I imagine you’ll find some diversion in this movie.”

Actually, you’ll find quite a bit.

End of program notes, back to Cinedrome post. The weekend drew to a close on Sunday evening with The Great Hospital Mystery (1937), a nifty little B whodunit from 20th Century Fox based on a short story by the prolific Mignon G. Eberhart and starring Jane Darwell as amateur sleuth Nurse Sarah Keats. (Actually, Eberhart’s character was named “Keate”. In 1935 Aline McMahon had played her under that name for Warner Bros. in While the Patient Slept, and in 1938, again at Warners’, Ann Sheridan would do it twice more [The Patient in Room 18 and Mystery House]. But this year, at Fox, she was “Keats”.) This one provided a good mystery, some well-placed comedy, a strong supporting cast (Sig Ruman, Sally Blane, Joan Davis, William Demarest) and a rare lead turn by supporting-actress powerhouse Darwell.

And there it is friends, my highlight-hopping rundown of this year’s Cinevent. Next year will be Cinevent’s Golden Anniversary, and I urge all my readers to plan on attending — especially if you live within driving distance of Columbus, Ohio, but even if you have to spring for airfare to get there. Believe me, it just possibly gives you the best bang for your buck of any classic-film festival in the world. And next year being the 50th, I’ll bet that the planners will have a lot of great things in store. Keep an eye on the Cinevent Web site as Memorial Day 2018 draws near, and mark your calendars now.