Picture Show 2022 — Day 3

Chapters 7-9 of Adventures of Red Ryder led off Day 3 of The Columbus Moving Picture Show. The evil machinations of banker Drake (Harry Worth) and his henchman Ace Hanlon (Noah Beery) grew ever more desperate and menacing as Red, Beth and Little Beaver drew closer to uncovering their conspiracy.

Then it was the welcome return of another longstanding Cinevent tradition: the Saturday Morning Animation Program, curated by the estimable Stewart McKissick. This year’s program (with YouTube links where available):

Then it was the welcome return of another longstanding Cinevent tradition: the Saturday Morning Animation Program, curated by the estimable Stewart McKissick. This year’s program (with YouTube links where available):

Bosko the Doughboy (1931). (Top row left) Bosko was the first Looney Tunes star, produced by Hugh Harman and Rudolph Ising, the most perfectly named partnership in movie history (“Harman-Ising”). They started out creating the Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies lines at Warner Bros., then when they got fed up with executive producer Leon Schlesinger they decamped to MGM and started the cartoon program there. Bosko the Doughboy came early in the Warner years, set in the trenches of the Great War. The Bosko cartoons hit TV in the mid-1950s when I was a kid, and frankly, I never liked them — partly because (as this picture shows) he was always eating, chomping with jaws gaping wide, the food bouncing around in his mouth. Even at age seven, I was disgusted. (I suspect that animators Rollin Hamilton and Max Maxwell simply couldn’t draw someone chewing with his mouth closed.) Now I’m able to watch these cartoons with more appreciation. Stewart McKissick says this one is often considered the best of the Boskos, and I believe it; there’s a startling strain of dark humor in the way it makes gags out of the bombs, machine guns and artillery shells of the Western Front — only 13 years after the war decimated a generation of European manhood.

Radio Girl (1932) was a Terrytoon with a succession of standard Depression-era gags draped on the premise of a radio exercise program. Like the YouTube video at the link, The Picture Show’s print was a 1950s TV syndicated version with new opening titles, but the rest was pure 1932.

Also from 1932 was Max and Dave Fleischer’s You Try Somebody Else (top row right), about a (literal) cat burglar newly released from prison. In short order he breaks into a house and raids the icebox filled with talking food. Caught by the homeowner, none other than a shotgun-toting Betty Boop, he goes back to the slammer, where he picks up a newspaper with a photo of Ethel Merman — and that’s all the excuse Max and Dave need to segue to Ethel in live-action for a follow-the-bouncing-ball singalong. The number is the title tune, one of the lesser-known works of the legendary songwriting trio of De Sylva, Brown and Henderson (“Good News”, “Birth of the Blues”, “Button Up Your Overcoat”, “Sunny Side Up” etc.). There was more dark humor at the end of this one.

Two-Gun Mickey (1934) (second row left) was Mickey Mouse from late in his black-and-white period, when he still had the comic spunk that would soon depart, leaving Mickey to play straight-man to Donald Duck and Pluto. As Stewart observes in his notes, at this point the Disney animation is smoother and more textured, but Walt’s drive for realism hasn’t yet banished the playful rubber-hose style of the early shorts. Dynamic and great fun.

The Headless Horseman (1934) (second row right) was a real revelation, and as such, just about my favorite entry on the program. One of Ub Iwerks’s ComiColor cartoons (produced during the six years he was lured away from Walt Disney by the Machiavellian Pat Powers), it’s an adaptation of Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” that beat Disney’s to the screen by 15 years. It’s quite a good one too: compact, witty, musical, with a pretty design that nicely conceals the limitations of Cinecolor. Spoiler alert!: The cartoon also makes explicit something that I didn’t see as a kid watching Disney’s version, and which was subtle enough to go over my head even when I read Irving’s story as a teenager: that Ichabod Crane’s run-in with the Headless Horseman is a prank played by Brom Bones to scare the superstitious schoolteacher out of the county and clear Brom’s path to Katrina Van Tassel. (Duh!) Iwerks’s cartoon lets that completely out of the bag, though it also ends with a nifty touch of the last laugh.

Bridge Ahoy (1936) (third row left) was one of the Fleischer brothers’ black-and-white Popeye cartoons. In this one Popeye and Olive Oyl are offended by the high-handed treatment they and Wimpy receive as they cross a river on Bluto’s ferryboat, so they decide to build their own bridge and put him out of business. One moment in this one that I’ve always loved: As the ferry pulls away from the riverbank, Wimpy says to Bluto, “I will gladly pay you Tuesday for a ferry ride today.” Bluto, furious, throws him overboard. As the indignant Popeye prepares to dive in and rescue him, we see Wimpy receding in the background, going down once, twice, three times, and each time he surfaces, he cries, “Assistance! Assistance!”

The Tangled Angler (1941) made a nice companion piece to Day 1’s Marry Me Again, since it was written and directed by Frank Tashlin before giving up cartoons for live action. Made during his brief one-year sojourn at Columbia’s cartoon unit between stints at Warner Bros. (the Looney Tunes influence is clear), it tells of the battle between a fisherman pelican and the slippery (in every sense) fish he can’t manage to land. UPDATE 7/21/23: I’m embarrassed to admit it, but The Tangled Angler wasn’t on the program after all; the supplier sent the wrong print, and by the time it arrived the program book had already gone to press. It was the book I relied on in writing up my coverage, and by then I’d forgotten about the change (these cartoons do tend to blur together if you’re not careful). What screened this year in Columbus was Tangled Travels (1944), also from Columbia, directed by Dave Fleischer, on the rebound from being bounced, along with his brother Max, from their animation studio at Paramount. Tangled Travels was a comic travelogue of the kind made during the 1940s over at Warner Bros., a series of punny “blackout” gags on geographical names and features (“We crossed a babbling brook…and a group of weeping willows…”). The Tangled Angler would have to wait another year, until Picture Show 2023, to join the Saturday morning cartoon program.

Rabbit Every Monday (1951) (bottom left) pitted Bugs Bunny against Yosemite Sam for the eighth of his 31 confrontations with the pugnacious little outlaw. I’ve always rather preferred Bugs’s duels with Sam over the ones with Elmer Fudd; Sam puts up more of a fight and is a worthier opponent than the hapless Elmer, who never seems to have a chance from the start. Besides, Sam is such an obnoxious blowhard that whatever he gets from Bugs, he’s got it coming. This was one of their few teamings where Sam is actually rabbit-hunting, almost as if he’s stepped in at the last minute because Elmer broke an ankle during rehearsals.

Rock-A-Bye Bear (1952) (bottom right) was prime Tex Avery screwball from his MGM years, with a dog named Spike hired to mind the house of a hibernating bear — but Spike has a spiteful rival who tries to get him fired by constantly making noise to wake up the sound-sensitive bear, hoping to replace Spike in the job. The picture here, also prime Tex Avery, gives a good idea of how the gags go in this one.

Barnyard Actor (1955) was a cleverer-than-usual Terrytoon starring Gandy Goose. Gandy receives a mail-order acting course, and immediately he is able to do impersonations of Groucho Marx, Jimmy Durante, James Cagney, Gary Cooper, and Charles Boyer (which isn’t the same as “acting”, but never mind). One very funny line, referencing Cooper’s role in High Noon (’52): “I’m the sheriff in these parts and I’ve got my duty to perform. I’m not deserting my post; I’d rather desert my wife.” The plot kicks in when Gandy’s pal Rudy Rooster asks him to impersonate a fox so he (Rudy) can chase him off and win the local hens back from the new rooster in the barnyard. Gandy agrees — but then a real fox shows up…

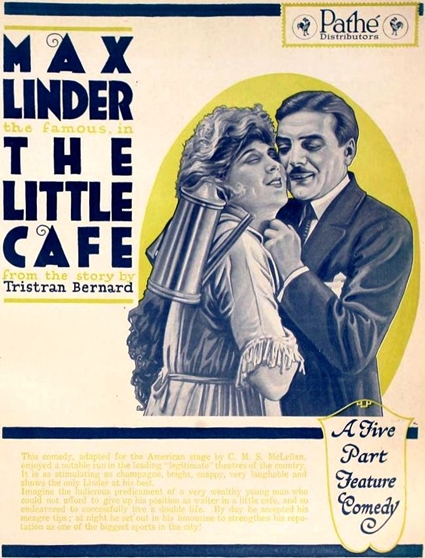

The cartoons were followed by The Little Cafe (1919) starring Max Linder. Linder (born Gabriel Leuvielle in 1883) was an early French film comedian, one of the first to establish a consistent screen persona, and by some accounts the first international movie star. He was certainly a recognized influence on Charlie Chaplin (whose fame quite eclipsed his, though they became and remained good friends), Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd and (yes) Charley Chase, among others. Alas, his heyday was not long. His career peaked around 1912-14, when the outbreak of World War I, and his experiences at the front as a dispatch driver and entertaining the troops, led to issues with his physical and mental health, including recurring bouts of depression. The Little Cafe was part of his efforts to regain his comic mojo after the war, and while a great success in Europe, it did not do well in the U.S. Based on a 1912 play by Tristan Bernard, and directed by the playwright’s son Raymond, it starred Linder as a waiter who suddenly inherits great wealth, but whose boss won’t let him out of his contract, hoping to extort a huge payment to let the fellow go. The screening was introduced by Linder biographer Lisa Stein Haven, author of The Rise and Fall of Max Linder: The First Cinema Celebrity. As for the “fall” of that title, I may write about it someday but I won’t spill the beans now, but rather refer you to Ms. Stein Haven’s book. Suffice it for now to say that in late October 1925 the 41-year-old Linder and his 19-year-old wife died together, and not of natural causes.

The cartoons were followed by The Little Cafe (1919) starring Max Linder. Linder (born Gabriel Leuvielle in 1883) was an early French film comedian, one of the first to establish a consistent screen persona, and by some accounts the first international movie star. He was certainly a recognized influence on Charlie Chaplin (whose fame quite eclipsed his, though they became and remained good friends), Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd and (yes) Charley Chase, among others. Alas, his heyday was not long. His career peaked around 1912-14, when the outbreak of World War I, and his experiences at the front as a dispatch driver and entertaining the troops, led to issues with his physical and mental health, including recurring bouts of depression. The Little Cafe was part of his efforts to regain his comic mojo after the war, and while a great success in Europe, it did not do well in the U.S. Based on a 1912 play by Tristan Bernard, and directed by the playwright’s son Raymond, it starred Linder as a waiter who suddenly inherits great wealth, but whose boss won’t let him out of his contract, hoping to extort a huge payment to let the fellow go. The screening was introduced by Linder biographer Lisa Stein Haven, author of The Rise and Fall of Max Linder: The First Cinema Celebrity. As for the “fall” of that title, I may write about it someday but I won’t spill the beans now, but rather refer you to Ms. Stein Haven’s book. Suffice it for now to say that in late October 1925 the 41-year-old Linder and his 19-year-old wife died together, and not of natural causes.

Before we move on, a parenthetical aside about Tristan Bernard and his son Raymond. The elder Bernard (1866-1947), a novelist, playwright, humorist and screenwriter, was the author of one of the most breathtaking insights in the history of art. “Audiences want to be surprised,” he once said, “but by something they expect.” His son Raymond (1891-1977) started out acting in his father’s plays with the likes of Sarah Bernhardt; in 1916 he embarked on a career that would, if anything, completely eclipse that of Bernard père and mark the son as one of the greatest of all French film directors. One film alone is enough to make him immortal; this is his 1934 adaptation of Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. Of all the 40-plus movies made from Hugo’s book, Raymond Bernard’s three-part, 281-minute version is by far the best; there’s not even a close second. For once — if not indeed for the only time — a movie is as great as the great novel it’s based on.

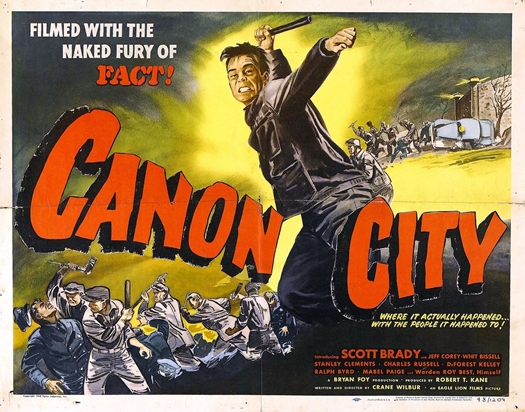

Okay, back to Columbus. Alan K. Rode, author of biographies of Michael Curtiz and Charles McGraw, gave a summary of the short history of Eagle-Lion Productions, an independent company set up by Britain’s J. Arthur Rank to distribute British movies in the States and produced low-budget American pictures for double bills. Then he introduced one of Eagle-Lion’s pictures, Canon City (1948), about a notorious prison break at the end of 1947 at the state prison in that Colorado town. (Incidentally, it’s “Cañon City”, pronounced “canyon”, not “cannon”. The movie gets the pronunciation right, but not the spelling.)

Okay, back to Columbus. Alan K. Rode, author of biographies of Michael Curtiz and Charles McGraw, gave a summary of the short history of Eagle-Lion Productions, an independent company set up by Britain’s J. Arthur Rank to distribute British movies in the States and produced low-budget American pictures for double bills. Then he introduced one of Eagle-Lion’s pictures, Canon City (1948), about a notorious prison break at the end of 1947 at the state prison in that Colorado town. (Incidentally, it’s “Cañon City”, pronounced “canyon”, not “cannon”. The movie gets the pronunciation right, but not the spelling.)

Like Glen or Glenda, Canon City was rushed into production to cash in on a hot news story, albeit to considerably better effect. The jailbreak took place on December 30, 1947; the picture was shooting by March ’48 on the prison grounds (with appropriate security, one hopes) and in post-production by April; its world premiere was held on July 2 in Canon City’s own Rex Theatre (which makes a cameo appearance in an early scene). Haste did not make waste, however; written and directed by Crane Wilbur, the picture is swift, efficient, and as tight as a snare drum, with a cast of solid character actors: Scott Brady, Jeff Corey, Whit Bissell, Stanley Clements, DeForest Kelly, Henry Brandon. The omniscient narration by Reed Hadley marks it as not film noir, but solidly in the semi-documentary tradition then being pioneered over at 20th Century Fox by producer Louis de Rochemont and director Henry Hathaway (The House on 92nd Street, 13 Rue Madeleine, etc.); Warden Roy Best even plays himself. Canon City is available complete here on YouTube. (Spoiler alert: Within a week of the break, all 12 escapees had been killed or recaptured — but audiences would all have known that in 1948.)

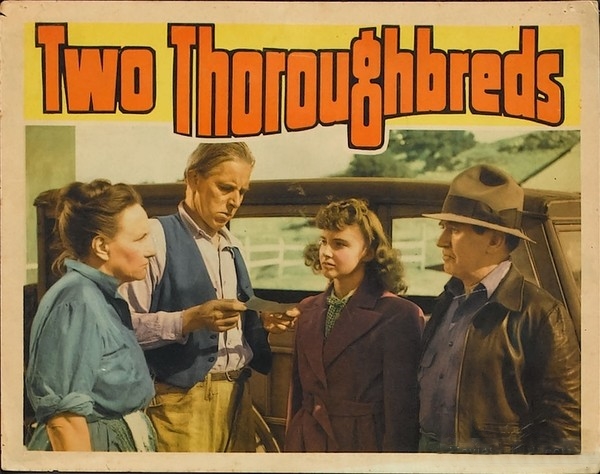

From hard-boiled prison drama to wholesome family fare, next came Two Thoroughbreds (1939). Here I interpolate the notes I wrote for The Picture Show’s program:

From hard-boiled prison drama to wholesome family fare, next came Two Thoroughbreds (1939). Here I interpolate the notes I wrote for The Picture Show’s program:

Everybody loves “a boy and his horse” movies, don’t they? Our offering here, an RKO B-picture called Two Thoroughbreds, is one that even the most dogged film buff has probably never heard of, but it’s a real charmer, and even a cursory glance at the cast list may lead you to wonder, “Why haven’t I known about this?”

Our story opens in the dead of night, as horse thieves hijack a valuable brood mare from a breeding ranch. As the thieves drive off, the mare’s recent foal gallops after them, whinnying plaintively, but is soon left in the dust. Exhausted and dispirited, the young animal wanders onto a nearby hardscrabble farm, where another orphan, a human one named David Carey (Jimmy Lydon), lives at the mercy of his abusive Uncle Thaddeus and Aunt Hildegarde (Arthur Hohl, Marjorie Main). David prevails upon Uncle Thad to let him keep the horse until they can find the owner; surely there’s a reward for such a handsome piece of horseflesh. But by the time David learns where the colt belongs, the two have bonded and David can’t bring himself to let go. Then Uncle Thad, tired of waiting for some pie-in-the-sky reward, decides he’ll either sell the colt or work it to death. What is poor David to do?

Two Thoroughbreds was filmed in the Lake Sherwood area of California’s Santa Monica Mountains, a location familiar to moviegoers from dozens, maybe hundreds of productions, from Douglas Fairbanks in Robin Hood (1922), which gave the lake its name, through Tarzan and His Mate and Frank Capra’s Lost Horizon, right down to Star Trek: Insurrection (1998) and Bridesmaids (2011). Sixteen-year-old Jimmy Lydon plays his first real role here — 1939 was his debut year in pictures, and so far he’d appeared only in Back Door to Heaven, an indie-B released through Paramount; The Middleton Family at the New York World’s Fair, a promo film for the fair’s Westinghouse exhibit; and a Robert Benchley short, Home Early — and he carries the 65-minute Thoroughbreds with ease. Stardom for young Jimmy was just around the corner, of course: In 1941 he would take on the role of Henry Aldrich in Paramount’s highly successful answer to MGM’s Andy Hardy series, then he’d become an early TV pioneer as “Biff” Cardoza on Rocky Jones, Space Ranger (1954), before settling in to a long and worthy career as a reliable character actor.

Stardom was in the cards for the perky, 14-year-old Joan Brodel, too — though not until Warner Bros. changed her name to Joan Leslie. Playing Wendy, the daughter of the colt’s rightful owner, she looks almost shockingly young here; it’s astounding to think that within three years she’ll be playing on-screen wives to Gary Cooper (in Sergeant York) and James Cagney (in Yankee Doodle Dandy).

And then there’s Marjorie Main. Her screen persona was still taking shape in 1939, the year of her breakthrough comic role in The Women, and the nasty old crone she plays here is a far cry from the Marjorie Main we know in Meet Me in St. Louis and The Harvey Girls. I wonder: Seven years later, when director Jack Hively was second-unit director on The Egg and I, did he and Marjorie ever reminisce about the difference between The Egg‘s Ma Kettle and the farm wife she played for him back in 1939? (Hively would remain a reliable journeyman director in movies and TV, often specializing in kids and animals, including 71 episodes of the long-running Lassie TV series during its Jon Provost/June Lockhart years and after, plus several TV movies with the canine star alone.)

Sharp-eyed viewers will notice one more familiar element in Two Thoroughbreds, and I’ll point it out now so you don’t miss any of the story trying to figure out where you’ve seen it before. This is the interior of the ranch house where the girl Wendy lives — that set also served as Katharine Hepburn’s Connecticut country house in RKO’s Bringing Up Baby the year before.

There’s an unhappy postscript to these notes. Almost the very day I turned them in to the program book’s editor, on March 9, 2022, veteran actor James “Jimmy” Lydon passed away at his home in San Diego, Calif. The Monday after The Picture Show, May 30, would have been his 99th birthday. (His wife of 59 years, Betty Lou, preceded him in death on January 1. I wonder if that bereavement perhaps hastened his own end.) The Columbus screening of Two Thoroughbreds was dedicated to his memory.

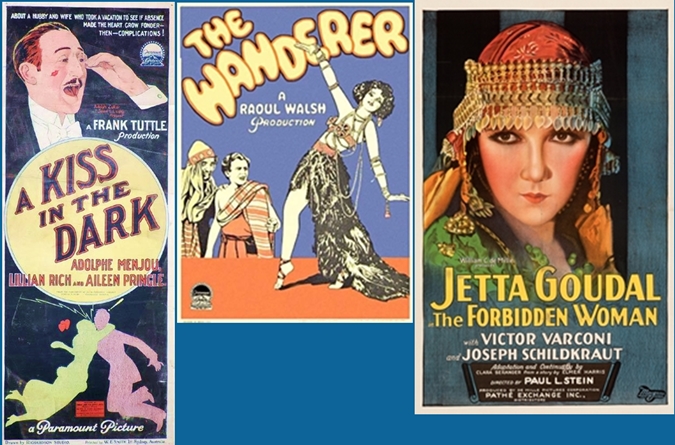

Silent movie historian Tim Lussier presented a program of Silent Fragments that was at once entertaining, tantalizing and frustrating. Frustrating because with each of the three titles he presented, the footage seemed to run out just as things were getting interesting. What we saw constituted fragments of fragments, actually, sort of teasers for the incomplete footage that survives. They were, in the order they’re presented in The Picture Show program:

A Kiss in the Dark (1925) This was (judging from what we could see) a surprisingly risqué romantic comedy about a serial seducer (Adolphe Menjou at his most dapper) who gets into hot water over a perfectly innocent misunderstanding with a married woman (Lillian Rich) — for once, a woman he was not trying to seduce. Supposedly based on Aren’t We All? by Frederick Lonsdale, the picture by all accounts had nothing whatever to do with the play except one character surname: in the play, Lord Grenham, an avuncular old nobleman, in the movie Walter Grenham, the young Lothario played by Menjou. Variety’s reviewer “Fred” ventured to wonder why Paramount bothered to buy Lonsdale’s play rather than just come up with this original and save the money. Maybe it was for the publicity value; Lonsdale’s name was highly admired in those days. Location shooting was done in Havana to take advantage of both the Cuban scenery and the fact that Prohibition didn’t extend down there.

The Wanderer (1925) A dramatization of the New Testament parable of the Prodigal Son, filling in a lot of story details that Jesus neglected to mention when He told the tale to His disciples. Longtime Cinedrome readers will recall that I reported acquiring a souvenir program for this picture in “Browsing the Cinevent Library, Part 2” in 2013. I had never heard of The Wanderer, but it was clearly a major Paramount production, directed by Raoul Walsh and starring Walter Collier Jr., Greta Nissen, Ernest Torrence, Wallace Beery and Tyrone Power Sr. Back in 2013 I reported that a print of the picture survived in the UCLA Film Archive. Not exactly; evidently what survives is a Kodascope six-reel condensation of the full nine-reel feature (see Day 1 notes on Flesh and Blood [1922] for more about Kodascope). We didn’t see all six reels in Columbus, of course, but there was enough to show that The Wanderer was a pretty lavish production, including scenes of the Sodom-and-Gomorrah-style destruction of the sinful city where the Prodigal squanders his inheritance.

The Forbidden Woman (1927) Set in French Colonial Algeria, Jetta Goudal played the half-caste daughter of an Arab mother and a French father. Charged by her sheik grandfather with spying on the conquering French, she first marries a French commander, then complicates things by falling in love with his brother (Joseph Schildkraut). Variety’s “Rush” predicted it would be a hit with “the femmes”, adding that “a little of this heavy Oriental romance goes a long way with men”. However, he did allow that “Miss Goudal…is outstanding in her clinging gowns and picturesque headdresses”, as the poster above attests. I found this the most frustrating of the excerpts Mr. Lussier presented, because it offered the fewest hints as to how the plot resolved itself. Unless I missed something.

The second and final Laurel and Hardy short of the weekend was Going Bye-Bye (1934), with killer Walter Long vowing vengeance against The Boys for testifying against him, swearing to…well, never mind what he swears to do; suffice it to say he does it.

The second and final Laurel and Hardy short of the weekend was Going Bye-Bye (1934), with killer Walter Long vowing vengeance against The Boys for testifying against him, swearing to…well, never mind what he swears to do; suffice it to say he does it.

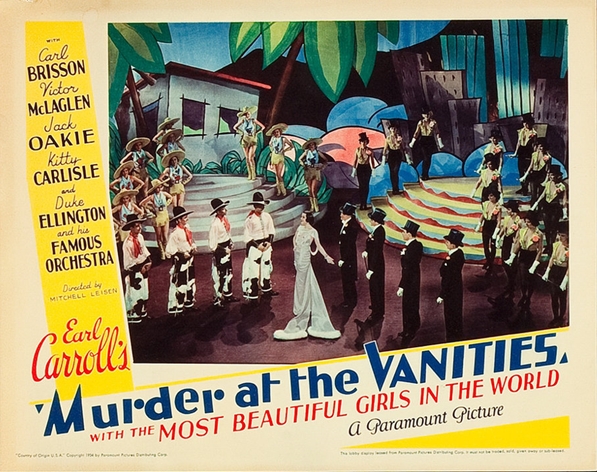

After that it was another highlight of the weekend, also from 1934, the genre-blending musical mystery Murder at the Vanities. The lobby cards for the picture, especially this one, are enough to make you wish it had been shot in Technicolor. But that would have meant postponing production until after the Production Code crackdown, in which case all those Most Beautiful Girls in the World would have had a lot more clothes on, instead of being as close to stark naked as state and federal obscenity laws would allow. Besides, the movie’s second-most-famous song would never have been included, and probably not even written; this was the remarkable “Sweet Marahuana [sic]”, a melancholy ode to cannabis sung by Gertrude Michael that made the movie a camp favorite among 1960s hippies after the demise of the Production Code.

Camp isn’t the only thing this jewel of Pre-Code Hollywood has going for it. The mix of musical and murder mystery is perfectly balanced by Producer E. Lloyd Sheldon and director Mitchell Leisen. The solution to the backstage crimes during opening night of Earl Carroll’s Vanities on Broadway, while not entirely unexpected, is smartly plotted and worked out. Leading man Carl Brisson was a touch too smarmy to be the Next Maurice Chevalier (which was obviously what Paramount had in mind for him), but he does no harm; besides, the real leading men are Jack Oakie as the show’s house manager and Victor McLaglen as an investigating cop, and they could carry anybody over the finish line. Musically, the songs are okay (with one legendary highlight), the production numbers lavish (with Ann Sheridan, Lucille Ball and Alan Ladd visible among the chorus if you look fast enough), and Duke Ellington and his Band are on hand to give Franz Liszt a swingtime treatment with “Ebony Rhapsody”.

That “legendary highlight” is the movie’s first-most-famous song, “Cocktails for Two”, one of the best and most popular songs of the decade — arguably better and more lasting than any of the three nominees that year for the first Best Song Oscar (“The Carioca”, “Love in Bloom”, and the winner, “The Continental”). “Cocktails” is introduced by Carl Brisson in rehearsal, then reprised later in a big production number and at the show’s finale, plus turning up frequently in the background all along — showing that the boys at Paramount really knew what they had. By the end of the decade, countless couples had designated it “their song”, and it had become enshrined as The Lounge Lizards’ National Anthem. (Ten years later, Spike Jones’s hilarious send-up infuriated songwriters Arthur Johnston and Sam Coslow, but it made them rich all over again.)

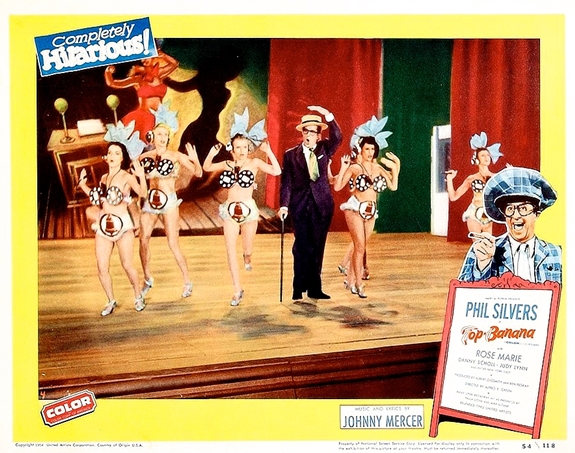

Day 3 wrapped up with Top Banana (1954), the screen translation of the 1951 Broadway musical comedy that won Phil Silvers the first of his two Tony Awards. I call it a “screen translation” because “adaptation” would be a misnomer. The show ran from November 1951 to October ’52 on Broadway, then Silvers toured with it for two years. It was while the tour was in Los Angeles that the sets were carted over to an empty sound stage and the show was transferred to film in a dizzying five days. No effort was made to “open it up” or conceal its stage origins; quite the contrary, the movie aspires to look exactly like a filmed stage production, complete with curtains, flimsy sets flown and rolled in, and stage lighting, including footlights. (It was also filmed in 3-D, but never released that way.)

Day 3 wrapped up with Top Banana (1954), the screen translation of the 1951 Broadway musical comedy that won Phil Silvers the first of his two Tony Awards. I call it a “screen translation” because “adaptation” would be a misnomer. The show ran from November 1951 to October ’52 on Broadway, then Silvers toured with it for two years. It was while the tour was in Los Angeles that the sets were carted over to an empty sound stage and the show was transferred to film in a dizzying five days. No effort was made to “open it up” or conceal its stage origins; quite the contrary, the movie aspires to look exactly like a filmed stage production, complete with curtains, flimsy sets flown and rolled in, and stage lighting, including footlights. (It was also filmed in 3-D, but never released that way.)

There have certainly been better movies made of Broadway shows, but Top Banana has a value uniquely its own to the show’s posterity: it is the closest thing we have to a precise record of what a show looked like during the Golden Age of the Broadway Musical. It’s also a specimen of the star-driven musical on the cusp of oblivion, before it was swept away by the irresistible wave of the integrated (and later the “concept”) musical, and of burlesque comedy before it got shouldered aside by striptease and more vulgar entertainments.

And talk about star-driven, the star here is firmly in the driver’s seat, and one of those newfangled hydrogen bombs couldn’t blow him out of it. Tony Awards in 1952 were announced without preliminary nominees, and it’s hard to imagine who could have been nominated against Phil Silvers. His only possible competition was Yul Brynner in The King and I, and under Tony rules Brynner wasn’t an above-the-title star so they weren’t in the same category. (Brynner won that year for outstanding “featured” — i.e., “supporting” — actor.) Bosley Crowther in the New York Times noted that, as he had been on Broadway, Phil Silvers was “ninety-nine one-hundredths” of the movie, and Silvers is practically a force of nature. The supporting cast includes some other burlesque veterans — Joey Faye, Herbie Faye (no relation), and Jack Albertson, still years away from his own stardom — but they are little more than Crowther’s other one-hundredth; Phil Silvers is the whole show.

(Rose Marie co-starred with Silvers on Broadway, and the show was almost as big a triumph for her, with four strong Johnny Mercer songs to leaven Silvers’s nonstop clowning. The movie was another story. In both her autobiography Hold the Roses and in Wait for Your Laugh, Jason Wise’s documentary about her career, she tells a story of being propositioned by the picture’s producer in front of the whole cast, and of her rebuffing him just as publicly. Her husband told her that her four songs in the show would be cut out of the movie, and he was right. Rose Marie doesn’t name the producer, but it’s pretty clear she’s talking about Albert Zugsmith. The story is not hard to believe.)

One misstep in the movie, I think, was not filming it before a live audience, or at least dubbing in a laugh track. Director Alfred E. Green inserts shots of a theater audience from time to time, and there’s applause on the soundtrack every now and then. But there’s no reaction to any of the comedy, much of which follows the Muppet Show principle that a joke that’s not good enough to use once may be bad enough to use six times. That kind of comedy needs the contagion of laughter, otherwise the jokes — bellowed at the top of the actors’ lungs, like verbal artillery barrages — tend to fall flat. For all that, though, and despite Rose Marie having been reduced to little more than a walk on, Top Banana is a valuable relic; it’s like finding a videotape of Weber and Fields or Smith and Dale in their prime.

And finally, there was one terrific bonus in Columbus this year. The DVD of Top Banana available from the Warner Archive, and even the version that pops up now and then on Turner Classic Movies, is missing a full 18 minutes, with several glaring holes where actors, sets, and costumes suddenly change in the middle of a sentence, sometimes in the middle of a word. The Picture Show screened a complete 100-minute print struck in 1954. I can only imagine where they found it, but we all counted our blessings.