Minority Opinion: The Magnificent Ambersons, Part 4

“Who knows what happened?” Orson Welles asked Barbara Leaming in 1984. “I was all covered in confetti trying to pretend I like carnivals, you know. I hate carnivals…” Welles may have been indulging in a little rueful hindsight 40 years after the fact. Simon Callow’s magisterial biography of Welles (two volumes so far, a third and fourth to come), draws on contemporary letters, telegrams, memos and news stories to present a very different picture of Orson Welles in Rio from the one he drew for Leaming.

“Who knows what happened?” Orson Welles asked Barbara Leaming in 1984. “I was all covered in confetti trying to pretend I like carnivals, you know. I hate carnivals…” Welles may have been indulging in a little rueful hindsight 40 years after the fact. Simon Callow’s magisterial biography of Welles (two volumes so far, a third and fourth to come), draws on contemporary letters, telegrams, memos and news stories to present a very different picture of Orson Welles in Rio from the one he drew for Leaming.For one thing, this wasn’t any old “carnival”, some smattering of rides set up in a pasture somewhere with booths for the locals to shoot pellets at plywood ducks and toss dimes into glass candy dishes. This was Carnival, a four-day samba-flavored bacchanal leading up to Ash Wednesday that made Mardi Gras in New Orleans look like a Methodist ice cream social, with a history stretching back to 1723. It’s clear from the record that Welles waded into Carnival with both feet — literally, grabbing one of his crew’s 16mm cameras and venturing out among the millions of revelers to get close shots, emerging drenched with sweat like a man coming out of the sea, all while his Technicolor cameras stood back to get the big picture, lit by the carbon-arc glare of anti-aircraft searchlights. Moreover, his notes and directives to his on-scene staff show that he saw the social and historical roots of Carnival as the core of the Brazilian section of It’s All True — a picture that was growing in scope and ambition by the day, even as Welles remained sketchy about the nuts and bolts of precisely how to get it made.

I don’t want to get sidetracked onto It’s All True, that landmark fiasco from which Welles’s career never recovered. That’s a whole other can of worms. What concerns me here is its effect on Ambersons. When Welles told Barbara Leaming about hating carnivals, he was burnishing the legend of Ambersons being snatched from his loving hands while his back was turned. In fact, at the time, he was reveling in his Brazilian adventure; the movie he was planning appealed to his experimental impulse to let a project find its own shape without conforming to a script, and he reveled as well in immersing himself in this exotic foreign culture. To say nothing of the patriotic duty he was discharging in the cause of inter-American relations.

Welles was fully engaged in shooting Carnival, in recreating sections of it afterward to shoot details his crew had been unable to capture during the crush and riot of the real thing, in mapping out (however vaguely) the other episodes of It’s All True, and in being feted and celebrated as the U.S.’s goodwill cultural ambassador. Fully engaged, but not, it must be said, to the exclusion of all other things; he was still in frequent contact with Robert Wise about Ambersons and with Jack Moss about both Ambersons and Journey into Fear. His ambitious ideas for It’s All True even spilled over into the two pictures he’d left behind: He wanted to shoot some new scenes for himself in Journey, which would mean sending his costume and makeup as Col. Haki to Rio. He wanted to hold the world premiere of Ambersons in Buenos Aires (“resultant international publicity will be enormous”, he wired Schaefer), and to record the picture’s narration in both Spanish and Portuguese. For his part, Schaefer didn’t relish the thought of Welles venturing another 1,200 miles farther from home; a Rio premiere maybe — maybe — but Buenos Aires was out of the question. On February 27, he politely reminded Welles that they still needed to get Ambersons ready for its Easter Week opening in New York (Easter Sunday that year would be April 5); time and tide, Orson, time and tide.

In response, Welles put the Ambersons crew in Hollywood on triple shifts editing and shooting new footage; Wise’s assistant Mark Robson later remembered the two of them moving into a motel near the studio and working as much as 120 hours a week. Even before Welles received Wise’s 132-minute cut, he had ordered the “big cut” and other changes, which Wise made in time for the first preview in Pomona.

1. George tells Eugene that he’s not welcome at Amberson Mansion, slamming the door on him; then —

2. Eugene writes to Isabel, begging her to be strong; then —

3. Isabel reads Eugene’s letter and drops dead (or at least dying) on the spot.

To paraphrase Oscar Wilde, it would take a heart of stone not to weep with laughter at a turn of events like that.

There were other things the Pomona audience didn’t care for. Most of all, they didn’t like Tim Holt. Or more to the point, they didn’t like George Amberson Minafer; Wise reported to Welles that Holt got “a reaction that said: ‘Oh, God, here he is again.'” Indeed, it’s hard to deny that the protagonist of The Magnificent Ambersons is an arrogant, destructive little bastard. In the novel, Tarkington had built sympathy for George despite the awful things he does, giving readers his inner thoughts (however misguided), and sugar-coating this pill much the way Margaret Mitchell finessed the fact that Scarlett O’Hara is a cruel, selfish, conniving bitch. Tyrone Power might have created more sympathy in an audience, as Vivien Leigh did for Scarlett (Prof. Carringer says the same about Welles himself), but Holt had a tougher time hoeing that row. The second half of the so-called “kitchen scene”, where George and Uncle Jack tease Fanny until she runs from the room in tears, originally continued with George spotting the Major’s new houses under construction through the window and running out into the rain to shout his outrage over the roar of the storm — and, in Pomona, over the screams of laughter from the audience.

George Schaefer was in the house that night, and he was rattled to his very bones. RKO had $1 million in Ambersons, and his position at the studio was on the line. Schaefer was Orson Welles’s best friend at RKO, but Schaefer himself had enemies who had been biding their time, ready to pounce. His support for Welles was a large part of it, but not all. Besides the uproar over Citizen Kane and its under-performance at the box office, there had been other expensive losses on Schaefer’s watch. Two of his closest lieutenants had already been sent packing; the tigers were at the gate.

The next day a panicky Schaefer queried RKO’s lawyers about the possibility of — if need be — taking Ambersons out of Welles’s hands. Their answer: Welles’s new contract relinquished his unprecedented right of final cut. He now had the right to cut the picture up to and including the first sneak preview; after that he was subject to the studio’s behest. Reassured, Schaefer waited to see what would happen.

Somewhere around this time Joseph Cotten chimed in, with a letter that Welles never answered and apparently never forgave — in 1984, talking to Barbara Leaming, he was still comparing Cotten to Judas Iscariot. After attending the Pomona preview, Cotten wrote that Welles’s script for Ambersons was “doubtless the most faithful adaptation that any book has ever had” but that “the picture on the screen seems to mean something else…It’s more Chekhov than Tarkington.” (“Yes, exactly!” Welles told Leaming. “That’s just what I was making!”)

Somewhere around this time Joseph Cotten chimed in, with a letter that Welles never answered and apparently never forgave — in 1984, talking to Barbara Leaming, he was still comparing Cotten to Judas Iscariot. After attending the Pomona preview, Cotten wrote that Welles’s script for Ambersons was “doubtless the most faithful adaptation that any book has ever had” but that “the picture on the screen seems to mean something else…It’s more Chekhov than Tarkington.” (“Yes, exactly!” Welles told Leaming. “That’s just what I was making!”)

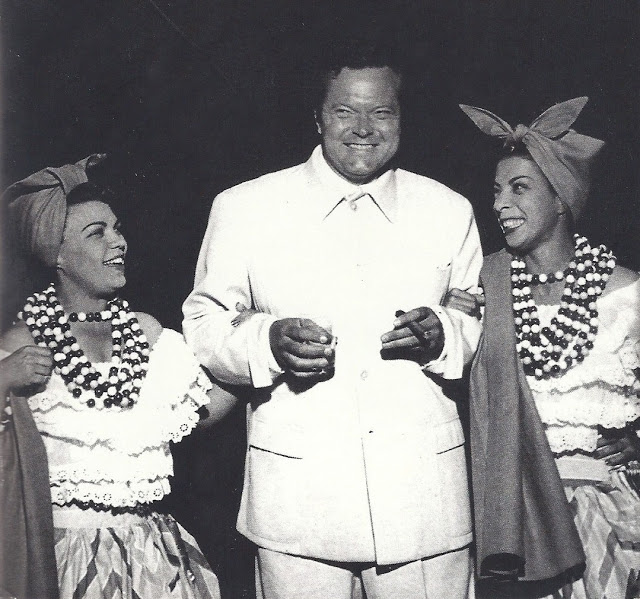

The focus of Cotten’s concern was the picture’s final scene, when Eugene visits Fanny at her boarding house and tells her of his reconciliation with George in the hospital room after George’s accident. That scene has been the focus of a lot of concern: Cotten was concerned at the time because it was in the picture; others since then, Welles among them, have been concerned because it was cut out and replaced. Even reading the scene in the cutting continuity, and looking at the surviving production photos like this one, it’s easy to see Cotten’s point. The scene is indeed Chekhovian — in fact, it’s reminiscent of the last scene of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya. In the play, Vanya’s niece Sonya speaks wistfully of the days to come, when their troubles will be behind them and “We shall rest”, while Vanya sits desolate and unhappy and a servant plays softly on the guitar. In the boarding house scene, Eugene tells of his making peace with George and being “true at last to my true love” while Fanny sits listless and impassive in her rocking chair and a corny comedy record plays on a Victrola in the background.

Simon Callow suggests that the boarding house scene was an improvement on Tarkington, something that’s beyond confirming or refuting now. What is certain is that it was a departure from Tarkington. Tarkington’s novel ends on a note of reconciliation and hope, even uplift; the boarding house scene ended Welles’s movie on a note of bleak melancholy, suggesting that the reconciliation was too little too late. Cotten, by calling the finished picture “something else” from what he experienced reading the novel, may not have grasped that something else was exactly what Welles was going for. On the other hand, Welles may not have fully grasped the unpleasant taste the scene left in its audience, and the pall it cast over the whole picture, because he never saw it with an audience — or indeed with anyone other than Robert Wise, once, in Miami, a month and a half ago, before the riotous distractions of Carnival and It’s All True.

On March 23, Jack Moss wired Welles with a detailed report describing both preview versions of Ambersons (which makes it possible now to calculate the running times and differences of both versions). Moss also laid out for Welles a compromise plan thrashed out by Robert Wise, Joseph Cotten and himself, which they felt would “remove slow spots and bring out heart qualities” of The Magnificent Ambersons.

It was, as things turned out, almost exactly the form in which the picture was finally released. Orson Welles was having none of it. “My advice absolutely useless,” he wired back on March 25, “without Bob [Wise] here…cannot see remotest sense in any single suggested cut of yours, Bob’s, Jo’s…cannot even begin discussing on proposals as received without doing actual work on actual film with Bob here.”

Moss assured Welles, rather disingenuously, that “every effort being made secure immediate passage for Bob”. But Welles probably knew better. In any case, he now prepared his own detailed plan. It would be his last attempt to retain control of the editing process going on a quarter of the world away.

To be continued…

Jim, as always, I'm truly wowed by all the work you did in whipping your stunning series "Minority Opinion: The Magnificent Ambersons, Part 4" into shape. Too bad Orson Welles didn't have as much focus and clarity in the making of his film as you've had in the writing of this series! As I've said in earlier parts of this series, the story-behind-the-story is as riveting as the story itself. Great job, Jim, as always!

Elisabeth, by a remarkable coincidence I first saw Ambersons in the summer of 1962, shortly after first reading Gone With the Wind. The comparison between George and Scarlett struck me, too — but when I mentioned it to an actress in the show I was doing, she refuted it rather forcefully and (to me) convincingly. Yes, she said, they're both the selfish, willful focus of wealthy families brought low by changing times. But the crucial difference is that Scarlett never gets her come-uppance. She ends as she began, airly dismissing an unpleasant thought: "I'll think about that tomorrow." She hasn't learned — implicitly, will never learn — that she can't always get her own way. "Those," my friend said, "are not the words of someone who's gotten her come-uppance." I couldn't answer her at the time, and now I think she was right.

Of course, it's important to remember that the ending of GWTW the novel is quite different from that of the movie — not in substance, but in tone. The movie ending stresses Scarlett's iron will and inner strength, while the novel underlines her fiddle-de-dee-ness and self-delusion.

I made the same comparison between George Minafer and Scarlett O'Hara when I read the book. They're protagonist and villain simultaneously, and it's something of a conjuring trick on the author's part to keep the reader interested in them. (And then, too, as I mentioned when I wrote a review of the book a year ago, perhaps it's partly the reader hanging on to see them "get their come-uppance", as Tarkington was so fond of saying.)

I think Ambersons is a tricky book to adapt in the first place, because some of the character motivations are rather hard to get across. George's primary motivation is his insane pride in "the family name," (arguably something he doesn't even really understand himself), and it's the idea that Isabel's remarriage would somehow reflect on "the family name" that prompts him to break it up. But isn't that rather hard to get across on the screen? Even some of the supporting characters, like Fanny and Lucy, seem like they would be harder to understand simply through their dialogue and actions. I haven't seen the movie yet, of course, so I can't judge how good a job it did with this.

On the other hand, some of the sequences in the book do seem very cinematic. The two vividly contrasting porch scenes, for example, showing how much has changed in the space of years between them, and the montage-like section after George and Isabel go abroad, where Tarkington describes the changes in the city.

Incidentally, in the book Fanny's companion in the second porch scene was Uncle George/Fred/Jack, not Major Amberson. I wonder why Welles didn't just go back to that when Richard Bennet wasn't up to the task?