Five-Minute Movie Star: Carman Barnes in Hollywood, Part 1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: For assistance in preparing this post, I am indebted to the University of Rochester River Campus Libraries, Department of Rare Books, Special Collections and Preservation, and particularly to Andrea Reithmayr, Curator of the Carman Barnes Papers. In addition, Thomas M. Lizzio conducted an on-the-ground exploration of Carman Barnes’s neighborhood during her sojourn in Hollywood, and Scott Miller and Jill Katz of Aerodrome Pictures kindly provided photographs of Carman’s former home. Finally, Lee Riggs of the Shields Library at the University of California Davis was instrumental in tracking down some of Carman’s novels that are no longer available for sale.

* * *

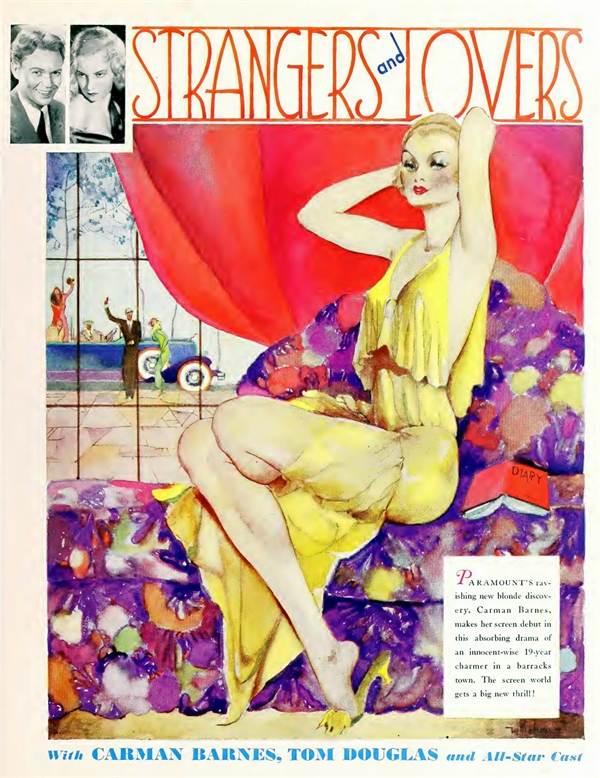

This ad is how Paramount Pictures heralded the coming of its “ravishing new blonde discovery, Carman Barnes”. Fittingly enough, the ad appeared in the Motion Picture Herald for May 2, 1931, in a lavish 74-page full-color supplement commemorating Paramount’s 20th anniversary and trumpeting the studio’s “1931-32 Product Announcement”. This magnum opus of ballyhoo makes fascinating reading, as the studio publicity department heaps praise on everyone from Adolph Zukor on down (including contract writers, lowest of the low on the Hollywood totem pole), then unveils dozens of concept posters like this one promising exhibitors that “even bigger hits are here and on the way.”

Truth to tell, this roster of features is more a wish list than a promise. Many of its titles would indeed come along that season: the Marx Brothers in Monkey Business; Daughter of the Dragon with Anna May Wong; Josef von Sternberg’s An American Tragedy; Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde with Fredric March, A Farewell to Arms, The Smiling Lieutenant, Love Me Tonight. Others would show up with different titles (Sternberg’s Indiscretion with Marlene Dietrich turned out to be Blonde Venus; This Is New York became Two Kinds of Women; Cheated morphed into The False Madonna) or different stars (Paul Lukas was replaced by Herbert Marshall in Evenings for Sale and by Irving Pichel in Murder by the Clock). And some wouldn’t be along for years: Gary Cooper in Graft showed up as George Raft in The Glass Key (1935); The Strange Guest was ultimately Death Takes a Holiday (1934), with poor Paul Lukas dumped again, this time for Fredric March. Still others — Manhandled with Clara Bow; Stepdaughters of War with Ruth Chatterton, Fay Wray and Jean Arthur — would never be made at all.

As things turned out, Strangers and Lovers was among those fated never to be — at least not under this title and, more to the point, not with Carman Barnes. This luscious specimen of Pre-Code titillation (the longer you look at it the sexier it gets) is in fact the high-water mark of Carman Barnes’s Hollywood career.

Reconstructing that career might be easier with access to the files and archives of Paramount Pictures, and maybe someday I’ll have the time and resources to delve into them. As it is, I’ve been able to draw on the few documents on the subject that survive in the Carman Barnes Papers at the University of Rochester’s River Campus Libraries, along with items gleaned from trade publications and fan magazines of the period. Fan magazines in particular must be approached with caution; they reveal a lot, but only through a glass darkly; what we read is filtered through layers of what studios wanted to share (or conceal) and what magazine writers and editors thought their readers wanted to know. It would tell us so much more if we had even a handful of memos from Paramount honchos discussing what to do with or about Carman Barnes.

In any case, Paramount first approached Carman in the late summer of 1930. By that time, she was the author of two published novels, Schoolgirl (1929) and Beau Lover (1930). Schoolgirl had been a sensation. Then came Beau Lover. For a 17-year-old even to have “lover” in her title was sensation enough, and the novel had a stylistic sophistication as eye-opening in its way as Schoolgirl‘s sexuality had been. (By way of comparison, in the 1950s teenager Francoise Sagan’s novels created a similar sensation — but Francoise was three years older than Carman had been. And French.)

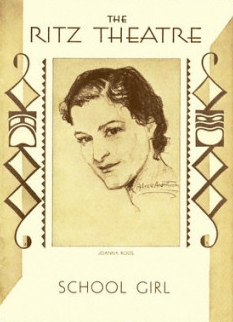

On September 3 that year, Variety announced that A.W. Pezet and Carman Barnes’s Schoolgirl (“from the latter’s novel”) would go into rehearsal on September 29 with Henry B. Forbes producing. Pezet would direct. Two weeks later, on September 16, Carman (and her mother Diantha, Carman being still a minor) signed a contract with Paramount Publix. She was to be paid $350 per week for six weeks, to begin when she reported to the studio in Los Angeles “on or about the 10th day of November, 1930, to write, compose, adapt and arrange such literary material as the Corporation may assign to her”. A.W. Pezet had been in Hollywood before Carman, and a letter from him that survives in her papers gives her an idea of what to expect when she gets there. The letter also talks about the casting of Naomi Bradshaw in their dramatization of Schoolgirl, and how they had been unable to get the services of a young actress named Bette Davis, she being already committed to another play, Solid South. (Ah, the coincidences and near misses of showbiz history!) Instead, to play the 16-year-old Naomi they went with 29-year-old Joanna Roos, fresh from a well-received production of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya with Lillian Gish and Osgood Perkins.

On September 3 that year, Variety announced that A.W. Pezet and Carman Barnes’s Schoolgirl (“from the latter’s novel”) would go into rehearsal on September 29 with Henry B. Forbes producing. Pezet would direct. Two weeks later, on September 16, Carman (and her mother Diantha, Carman being still a minor) signed a contract with Paramount Publix. She was to be paid $350 per week for six weeks, to begin when she reported to the studio in Los Angeles “on or about the 10th day of November, 1930, to write, compose, adapt and arrange such literary material as the Corporation may assign to her”. A.W. Pezet had been in Hollywood before Carman, and a letter from him that survives in her papers gives her an idea of what to expect when she gets there. The letter also talks about the casting of Naomi Bradshaw in their dramatization of Schoolgirl, and how they had been unable to get the services of a young actress named Bette Davis, she being already committed to another play, Solid South. (Ah, the coincidences and near misses of showbiz history!) Instead, to play the 16-year-old Naomi they went with 29-year-old Joanna Roos, fresh from a well-received production of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya with Lillian Gish and Osgood Perkins.

Schoolgirl opened at New York’s Ritz Theatre on West 48th Street (now the Walter Kerr). Opening night was November 20, 1930, Carman’s eighteenth birthday (with whoever laid out this playbill having separated the title into two words). Later, in an interview in Screenland Magazine, Carman told writer Margaret Reid, “It went over pretty well, but it got hell from the critics!” The show hung on for 28 performances before closing sometime in December. In fairness, 28 performances back then wasn’t the humiliating flop it would be now (Joanna Roos’s Uncle Vanya had run only 71), but it was far from the sensational hit Carman’s novel had been. (And by the way, if you’re thinking Bette Davis must have dodged a bullet, she didn’t do much better: Solid South opened on October 14 and closed 31 shows later. Shortly thereafter, Davis decamped to Hollywood and a screen test at Universal; Broadway wouldn’t see her again until 1952.)

In December Carman and her mother also left for California to embark on her six-week contract with Paramount. It’s reasonable to conclude that she reported for work at the studio on December 10, because exactly six weeks later, on January 21, 1931, she signed another contract with Paramount Publix. This one was for five years, at $1,000 a week, “to render services…as an actress and writer”. The contract hasn’t survived — not in Carman’s papers, anyhow — but she did preserve a copy of the petition filed with the California Superior Court requesting approval for this contract with a minor.

In December Carman and her mother also left for California to embark on her six-week contract with Paramount. It’s reasonable to conclude that she reported for work at the studio on December 10, because exactly six weeks later, on January 21, 1931, she signed another contract with Paramount Publix. This one was for five years, at $1,000 a week, “to render services…as an actress and writer”. The contract hasn’t survived — not in Carman’s papers, anyhow — but she did preserve a copy of the petition filed with the California Superior Court requesting approval for this contract with a minor.

What brought about the change from one contract to the next? Again, without access to Paramount’s files, we can only surmise. But here’s where those fan magazines really come in handy. It’s clear from reading their profiles of her that Carman had considerable personal charm to go with her precocious writing ability. And this portrait that ran in Silver Screen Magazine suggests that Sydney Valentine’s Screenland article comparing her to Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich may not have been as over-the-top as it sounds.

So what was Carman Barnes like at 18? She was five feet five inches tall and weighed 111 pounds — “slender,” one interviewer wrote, “to the point of breakability.” She had large, clear, almond-shaped brown eyes that tipped slightly upward. Phrases like “Garbo-ish eyelashes” and “[Gloria] Swansonesque nose” crop up in interviews. One magazine described her hair as red, another as “corn-colored”, and a third (a month later) as “blondined”. She spoke softly through full, rounded lips, in a voice “with the slightly plaintive inflection of the South.” Margaret Reid of Screenland flirted with cattiness by saying, “Her hair shows evidence of relations with a bottle and her nails are too tangerine — but she dresses in excellent, sub-deb taste and uses little make-up.” Her skin was youthful (of course) and palely translucent. She enjoyed writing, reading, sculpting, painting, swimming, horseback riding, dancing — more or less in that order. She expected to marry someday, and to have children (“I wouldn’t miss that experience for anything.”), but was in no hurry (“I have too much I want to do, and be.”). She struck people as level-headed, with a lively sense of humor. Self-confident without being conceited. Not conventionally beautiful, but attractive, even striking. And they noticed an indefinable quality about her that they cast about for words to describe — arresting, startling, exotic, transparent, fascinating.

As Gladys Hall put it in Motion Picture, “Jesse Lasky discovered that Carman was that rare apparition, a literary lady with looks“, and more than one magazine identified him as the instigator of the five-year contract, the raise from $350 to $1,000 a week, and the change in her job description from “writer” to “actress and writer” — in that order.

Paramount was indeed looking to replace Clara Bow. Clara had weathered the transition to talkies well enough — her voice suited her screen image and she was still popular. On the other hand, mike fright was never far off, and it sometimes paralyzed her; much of the fun had gone out of making movies. Meanwhile, her too-public private life had been just heedless enough that some of the lies and slanders about her were beginning to stick (and do to this day), adding to her emotional instability. Clara was worth indulging to a point, but the studio was losing patience with the continual sick-outs, rests and retreats. Couldn’t they find someone just as sexy, just as “now”, and as young as Clara was when they found her, but without all that baggage?

In that interview with Gladys Hall, Carman appears to address this very point. “The most important standard is to be discreet,” she told Hall:

“No matter what a girl does, if she is quiet about it, it’s all right and she’s all right. If she is noisy and advertises what she is doing, it is not all right.

“I know many a girl who has done all there is to do and has been quiet about it, gone her own way and said nothing, and she is admired and respected by everyone who knows her. I know other girls who have never done anything they wouldn’t do in Sunday School, but who make up glaringly, wear daring clothes and otherwise advertise themselves, and everyone thinks the worst.

“It isn’t what we do that matters. It is the way we do it.” [Emphasis in original.]

Even now, 86 years down the line, this mini-manifesto has an unmistakeable air of throwing-down-the-gauntlet about it. Certainly, to a fan reading it in 1931, there could be no mistaking — well, if not who Carman was talking about, then at least who Gladys Hall was thinking of when she wrote the article.

By the time this interview and others appeared in May 1931, the publicity push for Carman had been in full swing for some time. Any monthly magazine dated May would have hit the stands in mid-to-late April, and been in production for weeks before that. Certainly that 74-page color supplement in Motion Picture Herald (the one with the Strangers and Lovers poster that leads off this post) had been in the works for months. Indeed, in the 1931 Motion Picture Almanac (published in January) Carman is already listed among Paramount’s “New Leading Players” along with Ginger Rogers, Norman Foster, Miriam Hopkins, Stuart Erwin and others. In a paid Paramount ad in the same Almanac (“REASONS FOR THE MIGHTY DEMAND FOR PARAMOUNT ARE EASY TO STATE”), Carman — as well as Marlene Dietrich, the Marx Brothers, Maurice Chevalier, Ruth Chatterton, Charlie Ruggles, Kay Francis, etc. — appears under “Reason No. 4, such seat-selling personalities as:” — though of course Carman herself had yet to sell a single seat.

May and June profiles of Carman in Silver Screen (by Edward Churchill), Screenland (Margaret Reid) and Motion Picture (Gladys Hall) had been in the hoppers at their respective magazines since mid-January, when the writers interviewed Carman in the first flush of her new contract. By the time they appeared in print, Carman’s story was already changing. Margaret Reid in the May Screenland, for example, says that Carman and her mother are house-hunting (“I’ve been looking at houses all morning. I’ve never seen so much rococo in my life!”). But by then the hunt was long over, and Carman and Mama Diantha were ensconced in this house at 1975 De Mille Drive (shown here in a more recent photo). Today De Mille Drive is part of the exclusive, private gated community of Laughlin Park, but back then it was simply a semi-upscale residential street midway up the hill from Hollywood to the high ground of Griffith Park; C.B. De Mille himself lived just up the road. (The house is currently the home of Aerodrome Pictures, a design studio that provides graphics and branding for a range of entertainment companies.)

May and June profiles of Carman in Silver Screen (by Edward Churchill), Screenland (Margaret Reid) and Motion Picture (Gladys Hall) had been in the hoppers at their respective magazines since mid-January, when the writers interviewed Carman in the first flush of her new contract. By the time they appeared in print, Carman’s story was already changing. Margaret Reid in the May Screenland, for example, says that Carman and her mother are house-hunting (“I’ve been looking at houses all morning. I’ve never seen so much rococo in my life!”). But by then the hunt was long over, and Carman and Mama Diantha were ensconced in this house at 1975 De Mille Drive (shown here in a more recent photo). Today De Mille Drive is part of the exclusive, private gated community of Laughlin Park, but back then it was simply a semi-upscale residential street midway up the hill from Hollywood to the high ground of Griffith Park; C.B. De Mille himself lived just up the road. (The house is currently the home of Aerodrome Pictures, a design studio that provides graphics and branding for a range of entertainment companies.)

More important, all three articles mention Carman’s first project at Paramount as either Confessions of a Debutante, A Debutante Confesses, or simply Debutante, which Carman is to write and star in — but by May that was already obsolete. On February 11, Variety (always more on top of the entertainment news than any of the fan mags) ran an item headlined “Soft-Pedaling Barnes”:

Despite all the heavy advance plugs on Carman Barnes, girl writer, as a new Paramount star, she will be given merely featured billing on her first picture.

Billing will be freak, reading “Debutante,” by and with Carman Barnes.”

It was, in retrospect, an ominous sign.