Cinevent 50 — Day 3 (Part 1)

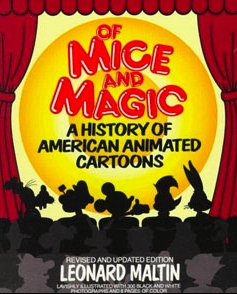

Saturday morning is always cartoon time at Cinevent. This year, in deference to the presence of Leonard Maltin, animation curator Stewart McKissick selected the program based on comments in Maltin’s seminal book Of Mice and Magic: A History of American Animated Cartoons. As Maltin himself said in the program notes, there were “no maverick opinions here”, and indeed, it was a morning of tried-and-true excellence (most of this year’s roster is not available on YouTube, so you’ll have to take my word for it). The morning included (among others) Max Fleischer’s Dizzy Dishes (1930), a cartoon cabaret that included the first appearance of Betty Boop when she was a leggy, voluptuous sexpot from the neck down and a sort-of puppy dog from the neck up; Porky Pig’s Feat, a 1943 black-and-white Looney Tune directed by Frank Tashlin, with Porky and Daffy locked in their hotel room until they can pay the bill; Tortoise Wins by a Hare (also 1943), with Bugs Bunny as Aesop’s perennial loser; and Hockey Homicide (1945), one of Walt Disney’s funniest “sports Goofy” shorts. The whole array culminated with two MGM shorts from Tex Avery in his prime: King Size Canary (1947), with a bird, a cat and a mouse constantly one-upping each other by guzzling “Jumbo-Gro” plant food and morphing into monstrous versions of themselves; and Little Rural Riding Hood (’49), another of Avery’s panting, libidinous variations on the famous fairy tale — not quite as woo-hoo!! sexy as Red Hot Riding Hood (’43), maybe, but just as funny.

Saturday morning is always cartoon time at Cinevent. This year, in deference to the presence of Leonard Maltin, animation curator Stewart McKissick selected the program based on comments in Maltin’s seminal book Of Mice and Magic: A History of American Animated Cartoons. As Maltin himself said in the program notes, there were “no maverick opinions here”, and indeed, it was a morning of tried-and-true excellence (most of this year’s roster is not available on YouTube, so you’ll have to take my word for it). The morning included (among others) Max Fleischer’s Dizzy Dishes (1930), a cartoon cabaret that included the first appearance of Betty Boop when she was a leggy, voluptuous sexpot from the neck down and a sort-of puppy dog from the neck up; Porky Pig’s Feat, a 1943 black-and-white Looney Tune directed by Frank Tashlin, with Porky and Daffy locked in their hotel room until they can pay the bill; Tortoise Wins by a Hare (also 1943), with Bugs Bunny as Aesop’s perennial loser; and Hockey Homicide (1945), one of Walt Disney’s funniest “sports Goofy” shorts. The whole array culminated with two MGM shorts from Tex Avery in his prime: King Size Canary (1947), with a bird, a cat and a mouse constantly one-upping each other by guzzling “Jumbo-Gro” plant food and morphing into monstrous versions of themselves; and Little Rural Riding Hood (’49), another of Avery’s panting, libidinous variations on the famous fairy tale — not quite as woo-hoo!! sexy as Red Hot Riding Hood (’43), maybe, but just as funny.

After the cartoons — and Chapters 7 to 9 of The Masked Marvel — the first feature of the day was The Eyes of Julia Deep (1918), one of the few surviving films of Mary Miles Minter. Over 80 percent of the 54 pictures she made between 1912 and 1923 are considered lost — which, in a way, is emblematic of the cloud this woman lived under for pretty much her whole life. I dealt with poor Mary in some detail in this post; click over to it if you want the sad particulars. For now, suffice it to say that she never really wanted to be an actress, and she appears to have had precious few happy days during her long life (she died at 82 in 1984).

After the cartoons — and Chapters 7 to 9 of The Masked Marvel — the first feature of the day was The Eyes of Julia Deep (1918), one of the few surviving films of Mary Miles Minter. Over 80 percent of the 54 pictures she made between 1912 and 1923 are considered lost — which, in a way, is emblematic of the cloud this woman lived under for pretty much her whole life. I dealt with poor Mary in some detail in this post; click over to it if you want the sad particulars. For now, suffice it to say that she never really wanted to be an actress, and she appears to have had precious few happy days during her long life (she died at 82 in 1984).

Like the photo reproduced here, The Eyes of Julia Deep gives us an inkling of why, for a while, Mary Miles Minter was considered a credible heiress apparent to Mary Pickford. She plays Julia Deep, a customer service clerk in a department store whose cheerful ways make friends for her wherever she goes. Living in the same boarding house with her is young Terry Hartridge (Allan Forrest), whose reckless lifestyle is fast burning through the fortune he inherited from his wealthy father. The two are not acquainted except by sight as they pass in the hall, but while he’s out frittering away his money on gambling and gold-digging women, Julia, with the landlady’s approval, finds escape from her humdrum shopgirl’s world among the books in his huge library. One night she falls asleep over a book and is still there when Terry comes home. He’s broke, depressed and suicidal; Julia, who’s been cowering in the shadows hoping to be able to sneak out unobserved, sees the pistol in his hand and impulsively pleads with him not to go through with it. From that, a friendship develops, with Julia taking charge of Terry’s finances and helping him straighten out his life. And friendship ripens into romance — until Terry’s irresponsible past comes back to bite them both in the heart. The Eyes of Julia Deep seesaws almost recklessly between comedy and drama, but director Lloyd Ingraham finesses the changing tone rather nicely. And there’s no getting around the fact that Mary Miles Minter really had something. She was never a serious rival to Mary Pickford — and wouldn’t have been, even without the bad luck, scandal and psychological stresses that plagued her. But she definitely had something.

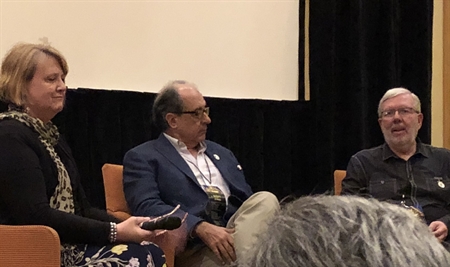

After the lunch break came a conversation in the screening room between Scott Eyman and Leonard Maltin. This picture shows (from left) moderator Caroline Breder-Watts, Scott, and Leonard. At the prompting of Ms. Breder-Watts, they spoke about what drew them to movies in the first place, and how they got into writing about them. I took scattered video of the session, and I’ll be posting separately on what they had to say. For now I’ll just say that it was a lively and diverting hour; Scott Eyman and Leonard Maltin, individually, are each excellent and stimulating company; together, they’re pretty tough to beat.

From there it was back to the movies, and the next one we saw would have been a highlight of the weekend for me, even if the presentation had been less spectacular than it was. The picture was George Pal’s The War of the Worlds (1953), and before I get into why it was such a particular highlight for me, let me say that the print we saw that afternoon was absolutely flawless — unblemished from first frame to last, with brilliant color that did full justice to George Barnes’s rich Technicolor photography (Barnes, an Oscar winner for 1940’s Rebecca, unfortunately did not live to see this last and best example of his art; he died in May 1953, three months before it was released).

And now my personal War of the Worlds story. It’s a story I recounted in the Cinevent 50th Anniversary commemorative book because it relates to my first visit to Cinevent in 1998.

The War of the Worlds, as it happens, is the subject of one of my earliest and most vivid memories of moviegoing. In December 1953, when I was five, my 23-year-old Uncle Conrad took me and two cousins to see the picture at the Enean Theatre in Pittsburg, Calif. I believe I sat through the first 15 minutes in relative aplomb, but when the lid popped off the top of the mysterious meteor and that weird metallic cobra head emerged, emitting a strange pulsing rattling noise, I felt the first stirrings of unease. And when Paul Birch, Jack Kruschen and Bill Phipps approached waving their sugar-sack white flag, only to be blasted to kingdom come, I became truly alarmed. Still, I held it together manfully (if I can use that word for my five-year-old self) through the first attack by the Martians, even when their sweeping heat ray hit the audience right between the eyes and thousands of soldiers, tanks and artillery were vaporized right before my eyes. To be sure, just as unease had given way to alarm, alarm now gave way to terror, but I was hanging on. Just barely.

And then I absolutely fell apart. It happened as Gene Barry and Ann Robinson were trying to dig their way out of that abandoned farmhouse with a Martian machine hovering outside. First, the sight of that alien periscope slithering down through the broken roof had me pretty close to panic. And when that Martian hand with its three suction-cupped fingers reached out and grabbed Ann Robinson by the shoulder, I lost it completely. I screamed, cried, few into hysterics, wailed at the top of my tiny lungs that I didn’t want to see it anymore. Uncle Conrad was torn, unsure how to handle this sudden outburst. Finally — and I honestly can’t say I blame him — his desire not to miss any of the movie won out, and he threw his windbreaker over my head, where I cowered for the rest of the movie. I sat there helplessly listening to Gene Garvin and Harry Lindgren’s groundbreaking sound effects, whimpering that I didn’t want to hear it either; whether Conrad and my cousins didn’t hear me, or whether they just ignored me, I never knew. Only at the end, as the Martian machines began crashing, did they coax me out from under Conrad’s jacket (“It’s okay, Jimmy, they’re dead now!”), so I did see that same Martian arm creep out on the open hatch and turn green in death.

In the short term, Conrad caught holy hell from the rest of the family for subjecting me to this shattering trauma. But I eventually recovered (to be honest, it took a couple of years), and once I got a firm grasp of the it’s-only-a-movie concept, I couldn’t wait to see it again. It became a staple of Saturday kiddie matinees in my childhood, and I probably saw it three or four more times by the time I was twelve.

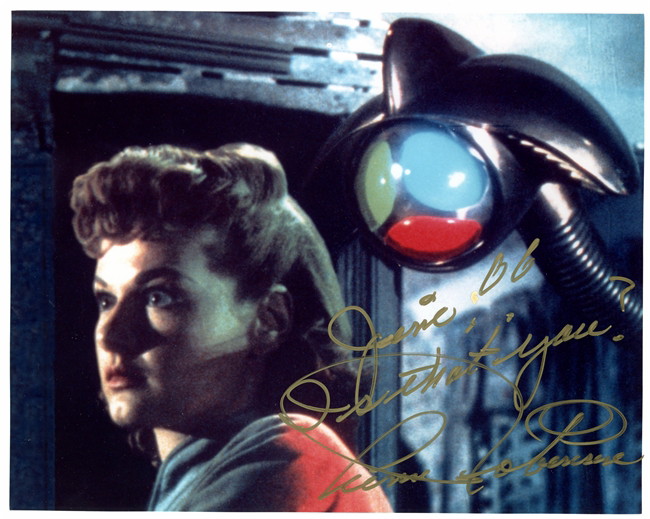

Fade out, fade in. It’s 1998, 45 years have passed, and I’m attending Cinevent in Columbus for the first time. In the downstairs lobby, just outside the dealers’ room, I saw none other than Ann Robinson herself, standing at a card table piled high with two stacks of photos — one of a black-and-white glamour shot of her from her days as a Paramount contract player, the other a production still of the Martian periscope looking over her shoulder, just before she turns around and sees it. I found Conrad in the dealers’ room, brought him out, and we introduced ourselves. Conrad took a picture of Ms. Robinson and me (it’s around here somewhere, but damned if I can find it). I told her the story of seeing The War of the Worlds in 1953 — and here’s the thing: She didn’t bat an eye. That’s when it finally dawned on me that I probably wasn’t the only five-year-old boy in 1953 who sat through that movie with his uncle’s coat over his head.

I may have lost track of the photo Conrad took of us, but I still have the shot of Ms. Robinson with the Martian periscope; it has an honored place in my collection. The inscription, in case you can’t quite make it out, reads: “Jim, ♥♥ Is that you? Ann Robinson”.

And on that note of personal reminiscence, I’ll close this review of the first part of Day 3. There was more to come.