Rhapsody in Green and Orange, Part 1

I’ve always had a tremendous fondness for King of Jazz (1930).

I’ve always had a tremendous fondness for King of Jazz (1930).

Partly, this is because of my fascination with the early days of sound, when the carefully compiled rule book of how to make motion pictures went flying out the window and everybody had to start over again from Square One. (I insert here a plug for Scott Eyman’s The Speed of Sound: Hollywood and the Talkie Revolution 1926-1930, the definitive chronicle of those chaotic years and one of the indispensible books on movie history. If you haven’t read it, do. You can thank me later.)

Looking back on those days when silent moviemaking went doggedly on even as part-talkies and all-talkies were becoming more and more dominant, we can see that the silent pictures of those transitional days, almost without exception, were vastly superior to the halting, lurching, lumbering experiments with sound that were coming out at the same time. Yes, they were better — but it didn’t matter. Audiences simply wouldn’t have the old stuff; they wanted talking pictures, and Hollywood had damn well better get with the program.

It was, in a way, an illustration of the old saw that said if you’re being run out of town, get out in front and make it look like a parade. While more and more picture houses, starting in the big cities and spreading out inexorable through the smaller markets, became wired for sound, the studios ransacked the theater world not only for talent but for ideas.

The 1920s on Broadway were the Golden Age of the Musical Revue, those hybrids of vaudeville and book musical comprised of singing, dancing, comedy and specialty acts, with no story but united under some all-encompassing theme. There were Florenz Ziegfeld’s annual Follies, of course, but also his Midnight Frolics, Earl Carroll’s Vanities, the Shubert Brothers’ The Passing Show, and a host of other annual productions and one-offs. In 1920, out of 55 musicals produced on Broadway, 16 were revues; in 1925 it was 15 out of 67; in 1929, 15 out of 63. The pattern holds for the entire decade: in any given Broadway season, no fewer than one in six musicals, and often as many as one in three, were revues.

Hollywood adopted the revue concept with alacrity. At MGM The Hollywood Revue of 1929 promised to be the first of an annual series (though it wasn’t); Warner Bros. came out with The Show of Shows, Paramount with Paramount on Parade, Fox with Happy Days.

At Universal it was King of Jazz, one of the first productions announced but, because of an expensive series of delays and false starts, the last one released. I’ve always found it the best of the bunch — sprightly, light on its feet, and in its way as daringly experimental as Citizen Kane. But as much as I’ve always liked King of Jazz, I now realize that I’ve never actually seen it.

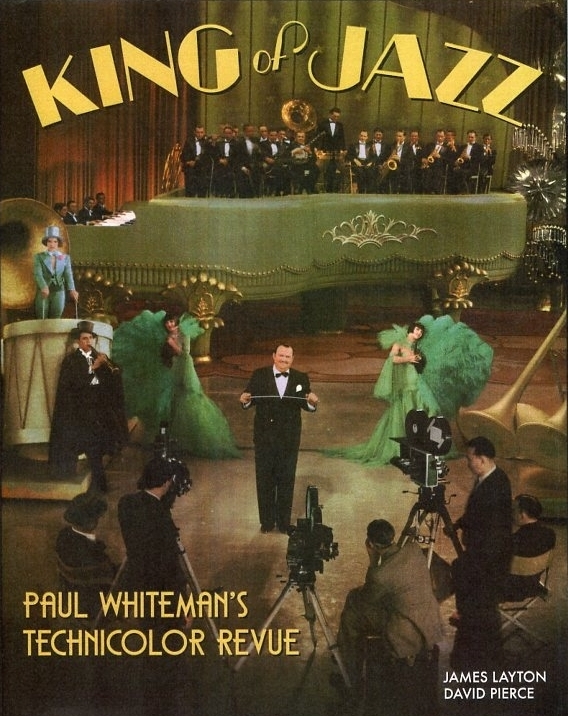

This disconcerting knowledge comes to me courtesy of a sumptuous, stunning new book, King of Jazz: Paul Whiteman’s Technicolor Revue by James Layton and David Pierce. (Full disclosure: I contributed $100 to the Kickstarter campaign to underwrite the book’s publication.) Layton and Pierce are the authors of the equally sumptuous and stunning The Dawn of Technicolor: 1915 – 1935, which was essentially a history of two-strip Technicolor, the process that was King of Jazz‘s second most important ace in the hole. (Its first was director John Murray Anderson, but I’ll get to him in a moment.)

This disconcerting knowledge comes to me courtesy of a sumptuous, stunning new book, King of Jazz: Paul Whiteman’s Technicolor Revue by James Layton and David Pierce. (Full disclosure: I contributed $100 to the Kickstarter campaign to underwrite the book’s publication.) Layton and Pierce are the authors of the equally sumptuous and stunning The Dawn of Technicolor: 1915 – 1935, which was essentially a history of two-strip Technicolor, the process that was King of Jazz‘s second most important ace in the hole. (Its first was director John Murray Anderson, but I’ll get to him in a moment.)

Layton and Pierce’s book chronicles the back story of King of Jazz, beginning with the founding of Universal Pictures and progressing through the studio’s venturing into sound picture production by signing a contract with superstar bandleader Paul Whiteman; the picture’s checkered production history; its brutal box-office reception; its decades of obscurity and near-lost status; gradual rediscovery beginning in the late 1960s; and its eventual election to the National Film Registry in 2013, which spurred Universal to undertake a digital restoration in 2015 (completed earlier this year).

This restoration, which premiered at the Museum of Modern Art in New York last May, brings King of Jazz (for the first time in 85 years) to within a few minutes of what audiences saw in 1930. And high time, too, because those of us who treasure King of Jazz have been basing our opinions on a “bastardized” version that first appeared on VHS in the 1980s.

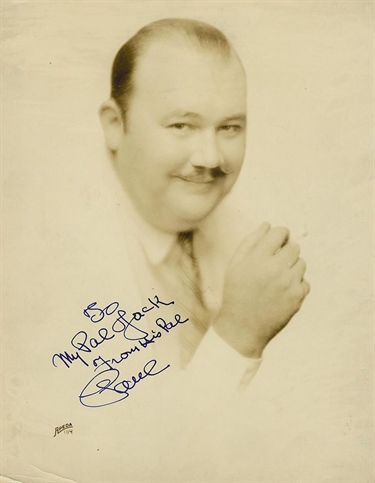

Photo courtesy Fulton family and Matias A. Bombal

I refer you to Layton and Pierce’s book to get the story in every fascinating detail. Here’s just a rough outline. In 1928 Universal signed bandleader Paul Whiteman to appear in the studio’s first all-talking picture, to be called King of Jazz — the sobriquet that had stuck to Whiteman, especially after he commissioned George Gershwin to compose “Rhapsody in Blue” for a 1924 concert at New York’s Aeolian Hall. (Note: I am indebted to the family of the late Jack Fulton, trombonist with the Whiteman band, and to Matías Bombal of Matías Bombal’s Hollywood, for this portrait of Whiteman, which the bandleader inscribed to Fulton in the 1920s.)

Actually, Whiteman was not (and did not pretend to be) a true jazz musician, but he knew a good hook when he heard it. Besides, he admired jazz and its practitioners, and he incorporated jazz styles and ideas into the carefully crafted arrangements that made his kind of music so wildly popular throughout the 1920s. The term “jazz” in those days encompassed the genre we’d call “pop” today (cf. the play and movie title The Jazz Singer, which is really about a pop singer); in that sense its application to Whiteman is fitting: he was, in his day, the true King of Pop — probably the first one, in fact.

Once Universal had Whiteman signed — on terms highly beneficial to the bandleader and his musicians, with perks that included the entire band’s salary and a special lodge built for them all to rehearse and relax in on the Universal City lot — the studio proceeded to…well…dither over exactly what kind of picture King of Jazz should be. The portly Whiteman was adamant that he was no actor (a point he would go on to prove in his later movie guest appearances) and he nixed any approach that would attempt to make him a romantic figure. With Hungarian emigré director Paul Fejos attached, story ideas were floated: a conventional biopic; a romance centering on two (fictitious) young people attached to the band, with Whiteman as a sort of father figure to the young lovers; and so on. Nothing jelled, and nothing met with Whiteman’s approval. Months passed; the band idled on Universal’s dime (except for their weekly radio show for Old Gold Cigarettes, which was broadcast from the West Coast) and the picture’s cost mounted without a single frame of film passing through a camera.

Finally, exit Paul Fejos and enter John Murray Anderson. Anderson, 43 in 1929, was one of the acknowledged masters (perhaps even the preeminent one) of the musical revue, having first made his mark with The Greenwich Village Follies, which moved from Sheridan Square to Broadway in 1919. The show packed ’em in for months and led to annual sequels for the next six years, then a final edition in 1928. Anderson’s hallmarks were taste, artistry and technical innovation on a modest budget.

Finally, exit Paul Fejos and enter John Murray Anderson. Anderson, 43 in 1929, was one of the acknowledged masters (perhaps even the preeminent one) of the musical revue, having first made his mark with The Greenwich Village Follies, which moved from Sheridan Square to Broadway in 1919. The show packed ’em in for months and led to annual sequels for the next six years, then a final edition in 1928. Anderson’s hallmarks were taste, artistry and technical innovation on a modest budget.

In 1925 Anderson signed with Publix Theatres, the distribution wing of Adolph Zukor’s Famous Players-Lasky Corp. (which owned and operated Paramount Pictures) to produce stage presentations for Publix theaters across the country. These “prologues”, designed to play before the main feature in motion picture houses, would be produced in New York and packaged to tour the Paramount circuit. (The practice was popular for years, but it would eventually wither with the changing economics of movie exhibition. Today its memory survives mainly in the premise of Busby Berkeley’s Footlight Parade of 1933; in fact, James Cagney’s character in Footlight Parade, Chester Kent, was probably inspired by Anderson).

After three years and over 50 shows, Anderson and Publix parted company over “creative differences” — i.e., Publix bridled at the shows’ increasing costs and Anderson resented Publix’s bean-counting. Anderson moved on to another Broadway revue, Murray Anderson’s Almanac, an ambitious project that folded after a disappointing run of only 69 performances.

By September 1929, with his Almanac in the process of flopping (it closed on October 12), Anderson was at loose ends. Fortunately, Universal came calling. They had abandoned the idea of making King of Jazz a story picture and now planned it as a revue. Their first choice to produce it, Florenz Ziegfeld, turned them down, so Whiteman suggested they approach Anderson. Anderson said yes.

After extensive consultations with Whiteman and Universal’s 21-year-old production chief Carl Laemmle Jr. (son of the studio’s founder), and preparations with set designer Herman Rosse (a longtime colleague of Anderson’s, with whom he had worked on Greenwich Village Follies and at Publix), production began on November 15, 1929 and concluded on March 20, 1930. The final product was, as Layton and Pierce aptly put it, “effectively a ‘greatest hits’ of John Murray Anderson and Paul Whiteman, mixed with the best elements of Broadway and vaudeville.” It featured musical performances by the Whiteman band and a variety of vocalists: John Boles, Jeanette Loff, Jeanie Lang, the Brox Sisters, and, in their screen debut, Whiteman’s Rhythm Boys: Bing Crosby, Al Rinker and Harry Barris. Interspersed with these were comedy blackouts performed by such studio contract players as Walter Brennan, Slim Summerville, Laura La Plante, and Glenn Tryon, plus Broadway import William Kent.

There was dancing, too. Most prominent in this area was a group of 16 high-kicking precision tappers then known as the Russell Markert Girls; in time this ensemble would come to be known as the Rockettes — first at New York’s 5,900-seat Roxy Theatre, then at Radio City Music Hall, where the group continues to this day. King of Jazz was, for them as for Bing Crosby, their movie debut.

There was dancing, too. Most prominent in this area was a group of 16 high-kicking precision tappers then known as the Russell Markert Girls; in time this ensemble would come to be known as the Rockettes — first at New York’s 5,900-seat Roxy Theatre, then at Radio City Music Hall, where the group continues to this day. King of Jazz was, for them as for Bing Crosby, their movie debut.

In addition to these proto-Rockettes there were the singing and dancing Sisters G (aka German-born Karla and Eleanore Knospe, who took the “G” from their stepfather Georg Gutöhrlein), two sweetly sexy lookalikes with Louise Brooks haircuts and impish European charm; and Al Norman, an eccentric “rubberlegs” hoofer who danced a specialty during the “Happy Feet” production number, where Sisters G and the Markert Girls also had their chance to shine.

From the start of production, it was understood that Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” would be on the bill somewhere — a Paul Whiteman movie without it was simply unthinkable. Gershwin accordingly demanded a pretty penny for the rights — $50,000 — and got it. But a more intransigent challenge was the fact that two-strip Technicolor couldn’t photograph blue; it could handle red and green, and various combinations thereof, but that was it.

Anderson and Rosse took a two-pronged approach: (1) they interpreted the title as meaning “blue” in the sense of “melancholy” or “singing the blues”; and (2) as Anderson described it in his autobiography, “Rosse and I made tests of various fabrics and pigments, and by using an all gray and silver background finally arrived at a shade of green which gave the illusion of peacock blue.”

Universal released King of Jazz with all the fanfare they could muster in April 1930, and early returns looked promising. Alas, once the picture moved beyond its early road-show engagements in the big cities, it tanked. The long shilly-shallying over what kind of picture it should be had been its undoing — it had run up costs while the Whiteman band bummed around Universal City and Los Angeles doing nothing much, and worse, it allowed the public to become bored with the whole revue genre. Universal, in effect, waited to strike until the iron was cold.

In Europe, which was behind America’s curve on sound and where musical revues hadn’t yet worn out their welcome, King of Jazz did much better than at home. But not well enough: the final take worldwide was $1.7 million and change, against total costs of a hair over $3 million; Universal lost over $1.2 million (as I’ve mentioned before, multiply these numbers by 100 to get an approximate idea of the value in 2016 dollars). Only the simultaneous bonanza of All Quiet on the Western Front saved the studio from disaster.