Ups and Downs of the Rollercoaster, Part 1

If there were such thing as a Dictionary of Stereotypical Characters, the entry for “eccentric inventor” would have a picture of Fred Waller. In the 1920s and ’30s, Waller’s day job was at Paramount’s East Coast studios in Astoria, Long Island, where he worked as a photographic jack of all trades. In one capacity or another he worked on, among other pictures, Male and Female (1921) for Cecil B. DeMille, and That Royle Girl (’25) and The Sorrows of Satan (’26) for D. W. Griffith. In the ’30s he produced and directed a series of innovative and visually striking jazz-flavored shorts featuring the likes of Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington and Fats Waller.

If there were such thing as a Dictionary of Stereotypical Characters, the entry for “eccentric inventor” would have a picture of Fred Waller. In the 1920s and ’30s, Waller’s day job was at Paramount’s East Coast studios in Astoria, Long Island, where he worked as a photographic jack of all trades. In one capacity or another he worked on, among other pictures, Male and Female (1921) for Cecil B. DeMille, and That Royle Girl (’25) and The Sorrows of Satan (’26) for D. W. Griffith. In the ’30s he produced and directed a series of innovative and visually striking jazz-flavored shorts featuring the likes of Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington and Fats Waller.

Meanwhile, on his own time, he tinkered and puttered. He invented a container for keeping food dry in humid climates, a remote-recording wind direction-and-velocity indicator, an adjustable sail batten for sailboats, and a still camera that could take a 360-degree panoramic picture. (Also, as I mentioned before, water skis, which he marketed as Dolphin Awkwa-Skees.) Through it all he continued his obsession with finding a way to photograph the full range of human vision, pursuing his idea that peripheral vision was as important to depth perception as binocular vision. He used to walk around his home wearing a baseball cap with toothpicks stuck in the brim, testing how far back he could place the toothpicks and still see them, mulling over the kind of screen he would need for what he had in mind.

In 1938, architect Ralph Walker came to Waller with a unique photography challenge connected with an exhibit Walker was designing for the petroleum industry for the upcoming New York World’s Fair. Walker envisioned a spherical room with a battery of projectors casting a constant stream of moving pictures, an idea that dovetailed neatly with what Waller had been turning over in his own head. With Walker’s firm, Waller formed the Vitarama Corporation, and by early 1939 he had a working model of eleven 16mm projectors showing a patchwork image on a concave quarter-dome screen suspended over the heads of the audience.

In 1938, architect Ralph Walker came to Waller with a unique photography challenge connected with an exhibit Walker was designing for the petroleum industry for the upcoming New York World’s Fair. Walker envisioned a spherical room with a battery of projectors casting a constant stream of moving pictures, an idea that dovetailed neatly with what Waller had been turning over in his own head. With Walker’s firm, Waller formed the Vitarama Corporation, and by early 1939 he had a working model of eleven 16mm projectors showing a patchwork image on a concave quarter-dome screen suspended over the heads of the audience.

In the end Walker’s clients, the representatives of the petroleum industry, decided not to use Waller’s Vitarama, opting for something simpler, more conventional — and, not incidentally, cheaper to produce and exhibit. Waller adapted the Vitarama idea for another exhibit at the 1939 World’s Fair, a huge mosaic slide show of still images for the Eastman Kodak exhibit. More important, the idea of the concave screen had solved Waller’s dilemma over how to project his multi-part images to envelop an audience.

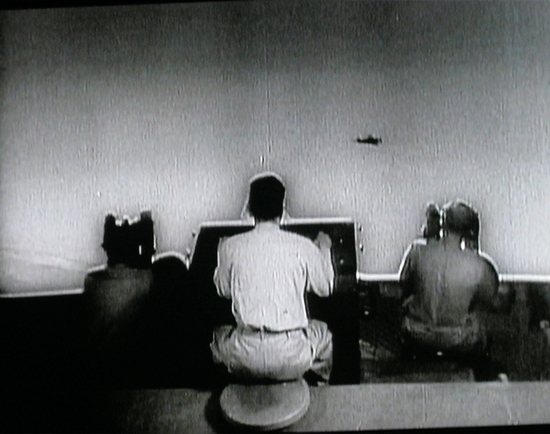

With a massive influx of military money (Waller later estimated it at over $5 million), the Waller Flexible Gunnery Trainer was born. It simplified the Vitarama design, using five 35mm projectors to display the same size image as the eleven 16mm ones, and it enabled Waller to work out the technical challenges involved in both the process itself and the manufacture of the equipment. Eventually 75 trainers, each occupying an area of some 27,000 cubic feet, were set up all over the U.S., in Hawaii, and in England, where over a million men were trained; the Air Force estimated that more than 250,000 casualties were averted thanks to this training.

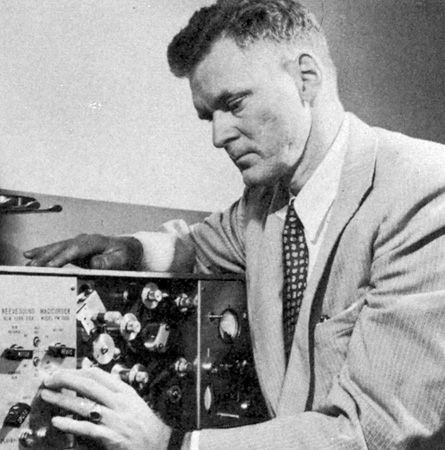

With a massive influx of military money (Waller later estimated it at over $5 million), the Waller Flexible Gunnery Trainer was born. It simplified the Vitarama design, using five 35mm projectors to display the same size image as the eleven 16mm ones, and it enabled Waller to work out the technical challenges involved in both the process itself and the manufacture of the equipment. Eventually 75 trainers, each occupying an area of some 27,000 cubic feet, were set up all over the U.S., in Hawaii, and in England, where over a million men were trained; the Air Force estimated that more than 250,000 casualties were averted thanks to this training. Also coming aboard at this time was Hazard E. “Buz” Reeves, one of the most brilliant and inventive men in the history of sound recording. Reeves had seen Vitarama as early as 1940, and was excited at the prospect of developing a sound system to go with it. Reeves and his company, Reeves Soundcraft, pioneered the use of magnetic recording for movies, a method more versatile than the standard practice of optical sound recording.

Also coming aboard at this time was Hazard E. “Buz” Reeves, one of the most brilliant and inventive men in the history of sound recording. Reeves had seen Vitarama as early as 1940, and was excited at the prospect of developing a sound system to go with it. Reeves and his company, Reeves Soundcraft, pioneered the use of magnetic recording for movies, a method more versatile than the standard practice of optical sound recording.

As Waller simplified the Vitarama/Cinerama process from five projectors to three, and from the quarter-dome screen to a wide curved rectangle (like the inner surface of a slightly flattened cylinder), Reeves developed a sound system to match: five huge loudspeakers behind the screen, each with its own discrete track, and a sixth track dispersed as needed to speakers placed at the rear and sides of the auditorium. (A seventh track, a composite of the other six, was intended only as an emergency backup and seldom used in practice.) Naturally, seven separate magnetic soundtracks required far more space than a standard optical soundtrack, so the sound was recorded on its own strip of 35mm film and run on a separate “projector” synchronized with the three image projectors just as they were synchronized with one another.

To be continued…

(PLEASE NOTE: For much of the information in this and following posts, I am indebted to the work of Dr. Thomas E. Erffmeyer, who wrote a history of Cinerama as his Ph.D. dissertation in Radio, Television and Film at Northwestern University [June 1985].)

It's true, Anon, Dave Strohmaier's Cinerama Adventure is a terrific documentary, and highly recommended. It's also included in the Blu-ray and deluxe DVD editions of How the West Was Won.

You can see all this come alive in a feature documentary that will air on Turner Classic Movies on Oct 18th. Its called Cinerama Adventure!

Jim, I'm glad to finally be able to read your series about the birth of Cinerama and its origins! Part One was quite intriguing, including the tests at Oyster Bay. I'm heading right over to Part 2! 🙂

I never knew any of this. Fascinating stuff. Looking forward to part two.