The Last Cinevent, the First Picture Show — Day 4

Day 4 of Cinevent 52 landed on October 31, Halloween itself. In keeping with the spirit of the day, the weekend’s Halloween theme made one final appearance in the form of a kinescope (film transcription of a live TV broadcast) excerpt from The Red Skelton Show of June 17, 1954. The 20-minute sketch — titled “Dial ‘B’ for Brush”, a reference to Hitchcock’s Dial “M” for Murder, then in release — offered Red’s dimwit character Clem Kadiddlehopper as a door-to-door brush salesman with just the kind of empty brain the local mad scientist is looking for to complete his latest sinister experiment. Guests on the episode, shown here with Red/Clem, were (left to right) TV horror-movie host and “glamour ghoul” Vampira (née Maila Elizabeth Niemi), Lon Chaney Jr., and the one and only Bela Lugosi. It was primitive fun; as would often be the case with Skelton’s long-running program, the flubs, mishaps, accidents and ad-libs were funnier than the script.

Day 4 of Cinevent 52 landed on October 31, Halloween itself. In keeping with the spirit of the day, the weekend’s Halloween theme made one final appearance in the form of a kinescope (film transcription of a live TV broadcast) excerpt from The Red Skelton Show of June 17, 1954. The 20-minute sketch — titled “Dial ‘B’ for Brush”, a reference to Hitchcock’s Dial “M” for Murder, then in release — offered Red’s dimwit character Clem Kadiddlehopper as a door-to-door brush salesman with just the kind of empty brain the local mad scientist is looking for to complete his latest sinister experiment. Guests on the episode, shown here with Red/Clem, were (left to right) TV horror-movie host and “glamour ghoul” Vampira (née Maila Elizabeth Niemi), Lon Chaney Jr., and the one and only Bela Lugosi. It was primitive fun; as would often be the case with Skelton’s long-running program, the flubs, mishaps, accidents and ad-libs were funnier than the script.

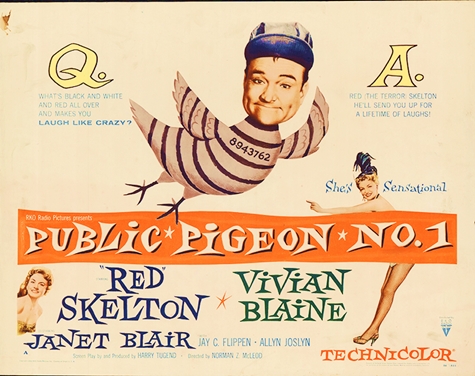

Besides the nod to Halloween, the sketch also served as an intro to Public Pigeon No. 1 (1957), Skelton’s last starring movie (his TV show would last until 1970, getting cancelled while still in the top ten, and he would make TV and big-screen guest shots until 1981). Even this had a TV origin, being a feature-length, Technicolor expansion of a comic episode of the live drama series Climax!, which Red had done in 1955. In both, he played a likable dope who gets duped by some con-men on a phony uranium stock deal (uranium was a popular plot device in those early days of the Atomic Age). When he winds up taking the fall for their swindle and going to prison, some G-men, knowing he’s only the patsy, arrange for him to break prison so he can lead them to the real crooks. The picture was okay, and Red was as good as ever (his prime was a long one) — but Public Pigeon No. 1 was, unfortunately, a product of RKO Radio Pictures in its last agonizing stage of being driven off a cliff and into the ground by Howard Hughes. It has the usual signs of cutting corners that can be seen in so many RKO pictures of the mid-’50s: the flimsy sets slapped together with a single coat of cheap paint, the lack of extras in the background (New York appears to have a population of about 45), the bare-bones soundtrack. Red, director Norman Z. McLeod, and the supporting cast (Vivian Blaine, Janet Blair, Jay C. Flippen, Allyn Joslyn, etc.) soldier gamely on, but there’s an unmistakable aura of sadness to the movie, like the last struggling store in a shopping mall slated for demolition. (Is that merely hindsight? Maybe so; at the time few people suspected that by the end of 1957 the studio would be sold and renamed Desilu.) Anyhow, pleasant as it is, Public Pigeon No. 1 is a definite step down from Red’s high-flying days at MGM.

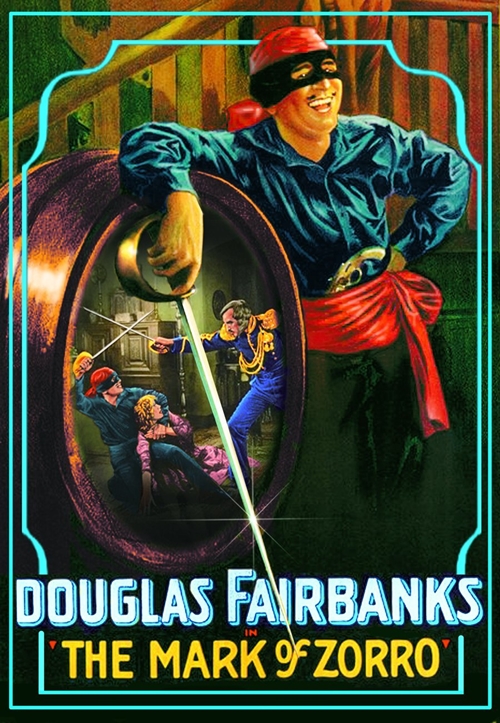

The Mark of Zorro (1920) is, like Frankenstein, another one of those needs-no-introduction movies. It was the first of Douglas Fairbanks’s costume swashbucklers; his movies made before then are best described as “athletic comedies”, a genre of which he was, and would remain, the chief practitioner (with honorable mention, perhaps, to Buster Keaton — and, long decades later, Jackie Chan). It was also the first of three signature masterpieces he turned out between 1920 and ’25. The next would be Douglas Fairbanks in Robin Hood in 1922 (he added his name to the title to keep some fly-by-night ripoff from siphoning off his audience), followed by The Thief of Bagdad in 1924. In 1930, if you had asked moviegoers to name a Fairbanks picture, odds are they would have mentioned one of those, or even all three, before getting around to The Three Musketeers (’21), The Black Pirate (’26) or The Iron Mask (’28).

The Mark of Zorro (1920) is, like Frankenstein, another one of those needs-no-introduction movies. It was the first of Douglas Fairbanks’s costume swashbucklers; his movies made before then are best described as “athletic comedies”, a genre of which he was, and would remain, the chief practitioner (with honorable mention, perhaps, to Buster Keaton — and, long decades later, Jackie Chan). It was also the first of three signature masterpieces he turned out between 1920 and ’25. The next would be Douglas Fairbanks in Robin Hood in 1922 (he added his name to the title to keep some fly-by-night ripoff from siphoning off his audience), followed by The Thief of Bagdad in 1924. In 1930, if you had asked moviegoers to name a Fairbanks picture, odds are they would have mentioned one of those, or even all three, before getting around to The Three Musketeers (’21), The Black Pirate (’26) or The Iron Mask (’28).

When Douglas Fairbanks died in 1939, his reputation as a star rested firmly on those three pictures: they seemed to be his lasting legacy, and they all hold up quite well today. By 1940 all three would be remade; as each remake loomed, the Hollywood buzz was that it was a fool’s errand to take on Doug’s classic, doomed to suffer by comparison. That’s what the proverbial “they” said about all three remakes — The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) with Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland and Basil Rathbone; The Mark of Zorro (’40) with Tyrone Power, Linda Darnell and Rathbone again; and The Thief of Bagdad (also ’40) with Sabu, Conrad Veidt and June Duprez. And yet each time, the remake not only stood up to Doug’s original, it absolutely blew it out of the water; Doug’s version would forever be overshadowed and made to look like just a primitive, halfway-decent first cut. Few silent stars have suffered that kind of comedown.

Tracey Goessel’s biography The First King of Hollywood: The Life of Douglas Fairbanks provides an excellent corrective to this undeserved eclipse, reminding us of how he bestrode popular culture at the height of his career. Zorro is a case in point. Johnston McCulley may have created the character, but it was Fairbanks’s movie that added the detail of carving a “Z” with his sword (hence the title change, The Mark of Zorro). And Fairbanks dressed him in black. True, this poster suggests his shirt was dark blue and the sash and bandana were red, but they photographed black, and black-clad Zorro would remain. Without Douglas Fairbanks, Zorro would be as forgotten today as any of the pulp heroes of his day whose names no one living recalls. (Have you ever read Johnston McCulley’s The Curse of Capistrano? I tried years ago; it’s awful.) We’d never have had the Tyrone Power remake, or the definitive 1950s Zorro of Guy Williams, or Frank Langella’s 1974 TV movie, or George Hamilton’s spoof Zorro: The Gay Blade (1981). (We wouldn’t have had those CGI-infested reboots with Antonio Banderas either, but the less said about those turkeys the better.) The Fairbanks/McCulley Zorro (nurturing the seed planted by Baroness Orczy’s Scarlet Pimpernel) also inspired generations of crime-fighting heroes (both human and super) hiding behind ineffectual, even foppish alter egos. Directly inspired, in the case of Bob Kane, creator of Batman: In Kane’s original story, young Bruce Wayne and his parents are returning from seeing The Mark of Zorro the night Bruce’s parents are killed, and the adult Bruce adopts Zorro-esque attire when he becomes “the Bat-Man”.

One last thing we can thank The Mark of Zorro for: In 1925 Fairbanks made Don Q Son of Zorro, the no-kidding, first-ever movie sequel. But let’s not be too hard on Doug; he didn’t live to see what a monster he created with that little innovation.

After the lunch break we got Chapters 10-12 of King of the Texas Rangers, with clean living triumphant and all villains getting their just deserts. Then came Dynamite Dan (1924), one of several pictures in which a Poverty Row indie producer named Anthony J. Xydias tried in vain to make a star out of one Kenneth MacDonald. I regret to say that nothing in Eric Grayson’s program notes made Dynamite Dan sound appealing, not even the prospect of an early performance by Boris Karloff (as “Tony Garcia”!), so I spent its 61-minute running time browsing the Dealers Room. However — again, if you’re curious — Dynamite Dan can be seen here on YouTube. Let me know if I missed anything.

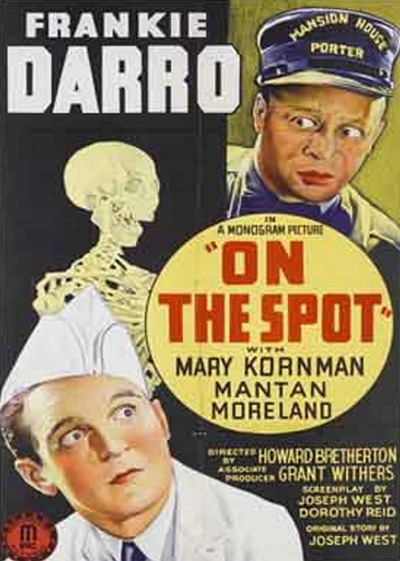

The last movie of the day — of the whole weekend, and of Cinevent’s 52-year history — was On the Spot (1940), a likeable little B-murder mystery/comedy from Monogram Pictures starring Frankie Darro and Mantan Moreland. Darro and Moreland made a number of these pictures, playing co-workers who are forced to become amateur detectives to solve a murder or two at their workplace. This time they’re working in a small-town drugstore — Darro as a soda jerk, Moreland as the janitor — when a notorious gangster, riddled with bullets, stumbles in, places a call in their phone booth, and falls over dead before he can say much. It turns out he was on the run after knocking over a bank for $300,000, and everybody — reporters, lawmen, and the gangster’s cronies — thinks he told Darro and Moreland where he stashed the loot. This one was out of circulation for years, probably considered lost if anybody ever gave it any thought, but resurfaced “a few years back” (per Dave Domagala’s program notes). It’s also available on YouTube, and worth spending an hour or so to watch; Darro and Moreland make a good team, and the story is actually pretty well-plotted.

The last movie of the day — of the whole weekend, and of Cinevent’s 52-year history — was On the Spot (1940), a likeable little B-murder mystery/comedy from Monogram Pictures starring Frankie Darro and Mantan Moreland. Darro and Moreland made a number of these pictures, playing co-workers who are forced to become amateur detectives to solve a murder or two at their workplace. This time they’re working in a small-town drugstore — Darro as a soda jerk, Moreland as the janitor — when a notorious gangster, riddled with bullets, stumbles in, places a call in their phone booth, and falls over dead before he can say much. It turns out he was on the run after knocking over a bank for $300,000, and everybody — reporters, lawmen, and the gangster’s cronies — thinks he told Darro and Moreland where he stashed the loot. This one was out of circulation for years, probably considered lost if anybody ever gave it any thought, but resurfaced “a few years back” (per Dave Domagala’s program notes). It’s also available on YouTube, and worth spending an hour or so to watch; Darro and Moreland make a good team, and the story is actually pretty well-plotted.

And that was that. Cinevent 52 was history, and so was Cinevent. Gone but not forgotten — and, in a real sense, not even gone. The Columbus Moving Picture Show takes it from here, so if you’ve grown accustomed to Cinevent (like me), or always meant to check it out, the CMPS is for you. Here are links to their Web site, their podcast, and their Facebook page. The schedule for May 26-29, 2022 is already taking shape, so hop on over, get on their mailing list, and I’ll look forward to seeing you in Columbus in five months. Be sure to say hi.