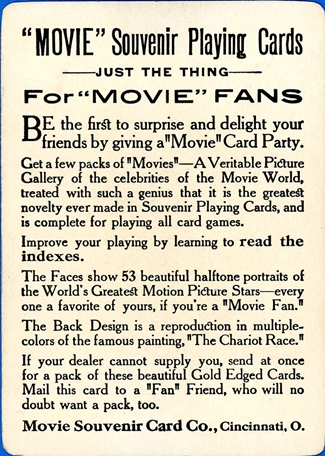

“MOVIE” Souvenir Playing Cards

Try to imagine a time when a deck of cards with movie star pictures was a novelty. It’s not easy, is it? We can hardly even imagine a time when a movie star was such a novelty that the word “movie” itself was in quotes. But here it is, courtesy of one M.J. Moriarty and the Movie Souvenir Card Co. of Cincinnati, Ohio.

Try to imagine a time when a deck of cards with movie star pictures was a novelty. It’s not easy, is it? We can hardly even imagine a time when a movie star was such a novelty that the word “movie” itself was in quotes. But here it is, courtesy of one M.J. Moriarty and the Movie Souvenir Card Co. of Cincinnati, Ohio.

The relative commonness of these decks at collector shows suggests to me that they were probably treated as collectibles from day one; people bought them to keep and look at the pictures, not to face the wear and tear of their Tuesday night whist clubs. (When was the last time you saw a 100-year-old deck of cards in perfect condition?)

That may be about to change. It’s becoming common practice among dealers now to break up the decks and sell the cards one at a time. At this moment in 2022, there are 54 individual cards available on eBay at prices ranging from five to twelve dollars. At that rate, a deck that Cliff Aliperti once said was worth no more than $150 (and which I’ve seen much lower) can bring a dealer as much as $630 or more. (Some cards are worth more than others, like this Charlie Chaplin Joker; it brings a premium because it’s the one instance where the card and the personality are perfectly matched — and probably also because Chaplin is the one person in the deck whom pretty much everybody recognizes.) This deck-splitting makes good business sense, but it probably means that decks that survived the last hundred years in near-mint condition are going to have a tough time making it through the next ten.

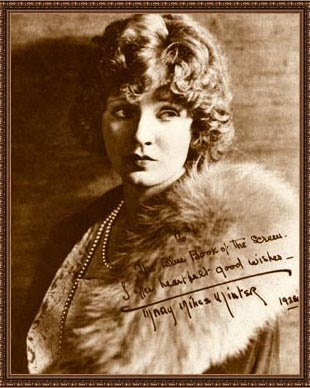

These decks first appeared in 1916 — at least that’s the copyright date on the card backing. Stars came, went, and changed positions in the deck, and some people (here, for example, at Cliff Aliperti’s Immortal Ephemera) have made a study of comparing and contrasting the decks that can still be found. Certain evidence of the cards themselves suggests that that they stopped production in 1922 at the latest: Wallace Reid appears on the 4 of Spades, and Reid died in January 1923; that’s not conclusive, though, because two other actors (Nicholas Dunaew and Richard C. Travers) occupied that card at one time or another. More persuasive is the case of Mary Miles Minter, the only occupant (so far known) of the 9 of Diamonds. Minter’s career was wrecked in the backwash of the William Desmond Taylor murder in February 1922, when her indiscreet love letters to the late director (30 years her senior) shattered her virgin-pure screen image. But even if the cards were still in production in 1922 (probably unlikely), they stopped pretty early. Many of the stars most associated with the silent era — Rudolph Valentino, Clara Bow, Greta Garbo, John Gilbert, Colleen Moore, Harry Langdon, Ramon Novarro, Bebe Daniels, Bessie Love — hadn’t made their big splash yet and don’t appear in any version of the deck.

Others might be expected to show up but don’t. Conspicuous by their absence are the King and Queen of Hollywood (even before their marriage made it official), Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford — although their colleague in United Artists, Chaplin, is Clown Prince of the deck. Dorothy Gish (5 of Clubs) appears, but not her sister Lillian, much the bigger star. And we have Mabel Normand (10 of Clubs) but not her teammate Roscoe Arbuckle, with whom she made dozens of popular Sennett comedies between 1912 and ’16. When these cards hit the market, Arbuckle’s legal troubles were still five years in the future, but he appears in no extant version of the deck, although “Fatty and Mabel” were as much a team as Laurel and Hardy would later be.

Now a word about the card backing — “the famous painting, ‘The Chariot Race'”, as the descriptor card says. The cards show only a detail; here’s a more complete look at the painting. It was indeed pretty famous during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, and was the work of Alexander von Wagner (1838-1919), a sort of Hungarian Norman Rockwell of the era.  Von Wagner painted at least three versions of the painting, the first one in 1873 for the Vienna Exposition. A second version went on display at Philadelphia’s Centennial Exposition in 1876, and another — or perhaps the same one — at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The painting sparked a national craze, with etchings and lithograph prints for sale everywhere. Contrary to what some have said, it does not reproduce a scene from Ben-Hur, which wasn’t published until 1880; indeed, the painting and its pop-culture clones may have inspired Gen. Lew Wallace to include such a scene in his novel. In point of fact, the full title of the work is “Chariot Race in the Circus Maximus, Rome, in the Presence of the Emperor Domitian”, which would have been several decades after Judah Ben-Hur and Messala had their fateful showdown in Antioch’s Circus Maximus. Only one of von Wagner’s versions of the painting is known to survive; it hangs today in the Manchester Art Gallery in England.

Von Wagner painted at least three versions of the painting, the first one in 1873 for the Vienna Exposition. A second version went on display at Philadelphia’s Centennial Exposition in 1876, and another — or perhaps the same one — at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The painting sparked a national craze, with etchings and lithograph prints for sale everywhere. Contrary to what some have said, it does not reproduce a scene from Ben-Hur, which wasn’t published until 1880; indeed, the painting and its pop-culture clones may have inspired Gen. Lew Wallace to include such a scene in his novel. In point of fact, the full title of the work is “Chariot Race in the Circus Maximus, Rome, in the Presence of the Emperor Domitian”, which would have been several decades after Judah Ben-Hur and Messala had their fateful showdown in Antioch’s Circus Maximus. Only one of von Wagner’s versions of the painting is known to survive; it hangs today in the Manchester Art Gallery in England.

But back to those 53 faces — “every one a favorite of yours”, according to the deck’s promo. So many of those favorites are forgotten today — victims of fickle audiences even in their own lifetimes, then victimized again by the passage of time and Hollywood’s too-little-much-too-late attitude toward film preservation. I thought it would be a fun project to take these cards one at a time and review what we can know now of the lives and careers behind those “beautiful halftone portraits.” Chaplin hardly needs it, of course, but what about House Peters, Mildred Harris, Wanda Hawley, George Larkin? I’ll be shuffling the deck from time to time, cutting the cards and seeing what comes up. Maybe we can uncover some sense of why these cards were bought, and enjoyed, and even cherished and preserved so carefully for a hundred years and more.

* * *

King of Hearts – H.B. Warner

Here’s an easy one for starters. Every true film buff knows Henry Byron Charles Stewart Warner-Lickford, although they might have to look twice to recognize the H.B. Warner they remember in this dapper, Arrow-collared, surprisingly youthful gent-about-town. This portrait may date from Warner’s entry into movies, when he was 38; that would have made the picture a couple of years old when the deck was published, but that sort of thing is not unheard of among actors’ head shots.

So film buffs know the name, even if the face comes as a bit of a surprise — but what about those less devout moviegoers, who don’t make a practice of memorizing the name of every Thurston Hall or J. Edward Bromberg who marches across the screen? Well, I’m going to go out on a limb here: I think it just may be that H.B. Warner’s work has been seen by more people alive today than anyone else in the M.J. Moriarty deck. Yes, maybe even more than Charlie Chaplin.

Note I said “seen by”, not “familiar to”. So take another look. Try to add, oh, maybe 30 years to that face. Look especially at the eyes. Ring any bells? Well…

In 1937, Capra gave Warner the opportunity to deliver probably his best screen performance. The picture was Lost Horizon, from James Hilton’s utopian romance about a group of refugees from war-torn “civilization” who find themselves in the remote Himalayan paradise of Shangri-La. Warner (here with Isabel Jewell, Edward Everett Horton, Ronald Colman and Thomas Mitchell) played Chang, their mysterious escort from the snowbound wreck of their plane to the Edenic Valley of the Blue Moon, and their host after they arrive. Endlessly cordial, welcoming and polite, he nevertheless is inscrutably vague about when and how they will ever be able to return to their homes. Warner got an Oscar nomination as best supporting actor, but he didn’t win; he lost out to Joseph Schildkraut as Alfred Dreyfus in Warner Bros.’ The Life of Emile Zola. That’s a worthy performance, but I’m not at all sure the Academy made the right call. H.B. Warner’s other pictures for Capra were You Can’t Take It with You (1938), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939, as the Senate majority leader) and Here Comes the Groom (1951).

In 1937, Capra gave Warner the opportunity to deliver probably his best screen performance. The picture was Lost Horizon, from James Hilton’s utopian romance about a group of refugees from war-torn “civilization” who find themselves in the remote Himalayan paradise of Shangri-La. Warner (here with Isabel Jewell, Edward Everett Horton, Ronald Colman and Thomas Mitchell) played Chang, their mysterious escort from the snowbound wreck of their plane to the Edenic Valley of the Blue Moon, and their host after they arrive. Endlessly cordial, welcoming and polite, he nevertheless is inscrutably vague about when and how they will ever be able to return to their homes. Warner got an Oscar nomination as best supporting actor, but he didn’t win; he lost out to Joseph Schildkraut as Alfred Dreyfus in Warner Bros.’ The Life of Emile Zola. That’s a worthy performance, but I’m not at all sure the Academy made the right call. H.B. Warner’s other pictures for Capra were You Can’t Take It with You (1938), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939, as the Senate majority leader) and Here Comes the Groom (1951).

But you don’t get your picture on a deck of cards for supporting and character roles in your twilight years, however memorable. What about his career earlier, when he appeared on the King of Hearts sometime between 1916 and 1920? Well, unfortunately, that’s something we’re going to bump up against over and over as we discuss this antique deck of cards — and for that matter, anything else about the silent era. The survival rate of movies made between 1890 and and 1920 is only a cut or two above snowball-in-hell level; for much of Warner’s career we have to piece together what information we can from secondary sources.

We know that he made his Broadway debut on November 24, 1902 at the age of 27 (billed as “Harry Warner”), in Audrey by Harriet Ford and E.F. Boddington. In 1910 he appeared in Alias Jimmy Valentine, one of the smash hits of the early 20th century stage, adapted from the O. Henry story “A Retrieved Reformation.” He must have made quite an impression in that, because in 1914, when he filmed another one of his stage successes, The Ghost Breaker, the laudatory review in Variety mentioned him as “he of ‘Jimmy Valentine’ fame.” The Ghost Breaker was his third picture in 1914, and was co-directed by Cecil B. DeMille. They would work together again, and would in fact make their last picture together — but more of that anon.

Warner was a veteran stage star by the time his movie career really got underway in the mid ‘teens, and he established himself (if we can believe his Variety reviews) as an appealing romantic lead in titles like The Raiders, Shell 43 and The Vagabond Prince (all 1916), Danger Trail (’17) and The Pagan God (’19). He continued to appear on Broadway until Silence in the winter of 1924-25 (which he also filmed in 1926); after that he was a Hollywood actor for good.

At least one of H.B. Warner’s silent movies has survived intact, and it’s a biggie: Cecil B. DeMille’s spectacularly reverent The King of Kings (1927), in which Warner played the title role. The movie was a triumph of prestige and box office for DeMille; in reviewing it, Variety’s legendary editor Sime Silverman was quite tongue-tied with awe; in 24 column inches, Silverman (normally so terse and pithy) fairly stumbles over himself groping for superlatives. The movie is a bit too earnestly pious for modern tastes, but its appeal for 1927 audiences is still understandable, and DeMille’s showmanship is at its smoothest. Most memorably, Warner’s performance, in an age when accusations of sacrilege were a very real concern, is excellent. Here’s a strikingly dramatic shot of him at the Crucifixion, seen from the viewpoint of Jesus’s mother Mary mourning at the foot of the Cross.

And here, just to give a flavor of the lavishness of DeMille’s picture, is a frame from one of King of Kings‘s two Technicolor sequences, showing the resurrrected Christ comforting Mary Magdalene (Jacqueline Logan) at the opening to the tomb on Easter morning. (On a curious side note: in King of Kings Judas Iscariot was played by none other than the self-same Joseph Schildkraut who ten years later would ace Warner out of that Oscar.)

H.B. Warner’s final screen appearance was a poignant one. He was approaching 80 and living at the Motion Picture Country Home in Woodland Hills in 1955 when the call came from his old friend Cecil B. DeMille. DeMille was planning a massive spectacle expanding the Biblical section of his 1923 hit The Ten Commandments, and he had a part for H.B. if he felt up to it. The role was identified in the script as “Amminadab”, an aging Israelite setting out on the Exodus from Egypt, even though he knows he’ll never see the Promised Land — indeed, probably won’t live out the day. The actor carrying him in this shot, Donald Curtis, remembered that Warner weighed no more than a child, and carrying him wasn’t merely in the script, it was a necessity: “It was clear H.B. couldn’t walk — could barely breathe.” He had come to the set in an ambulance and lay on a stretcher, breathing through an oxygen mask, until the cameras were ready to roll. In the script, he had a rather complex speech adapted from Psalm 22, but he couldn’t manage it, so DeMille told him to say whatever he wanted, and Curtis and Nina Foch would work with it. H.B. Warner’s last words in his 137th movie, after 53 years as an actor, were: “I am poured out like water, my strength dried up into the dust of death.”

H.B. Warner’s final screen appearance was a poignant one. He was approaching 80 and living at the Motion Picture Country Home in Woodland Hills in 1955 when the call came from his old friend Cecil B. DeMille. DeMille was planning a massive spectacle expanding the Biblical section of his 1923 hit The Ten Commandments, and he had a part for H.B. if he felt up to it. The role was identified in the script as “Amminadab”, an aging Israelite setting out on the Exodus from Egypt, even though he knows he’ll never see the Promised Land — indeed, probably won’t live out the day. The actor carrying him in this shot, Donald Curtis, remembered that Warner weighed no more than a child, and carrying him wasn’t merely in the script, it was a necessity: “It was clear H.B. couldn’t walk — could barely breathe.” He had come to the set in an ambulance and lay on a stretcher, breathing through an oxygen mask, until the cameras were ready to roll. In the script, he had a rather complex speech adapted from Psalm 22, but he couldn’t manage it, so DeMille told him to say whatever he wanted, and Curtis and Nina Foch would work with it. H.B. Warner’s last words in his 137th movie, after 53 years as an actor, were: “I am poured out like water, my strength dried up into the dust of death.” Movie Playing Cards: 9 of Diamonds – Mary Miles Minter

Charlotte had left Juliet and her sister Margaret with their grandmother, but she soon sent for them to join her in New York, where little six-year-old Juliet caught the eye of Charles Frohman, producer of the play Charlotte was appearing in. Kirkpatrick says Frohman cast the tot in Cameo Kirby and A Fool There Was — but neither play was produced by Frohman, and Juliet Shelby doesn’t appear in either cast on the Internet Broadway Database. Well, whatever the exact names or titles involved, Charlotte realized in short order that little Juliet was the meal ticket.

Juliet Shelby made at least one picture under that name in 1912, for Universal in New York: The Nurse (now lost, of course). Not long after that she caught the baleful eye of the Gerry Society, watchdogs over the exploitation of child labor and the bane of any show business troupe with underage players. Charlotte handled the matter creatively; she rushed back to Louisiana and borrowed the birth certificate — and name — of her sister’s daughter, who had died in 1905 at the age of eight. And hey presto! — eleven-year-old Juliet Shelby became sixteen-year-old Mary Miles Minter, old enough to satisfy the Gerry Society but looking young enough (because she was) to play the sort of roles for which she was in demand. By the time she made a hit on Broadway in Edward Peple’s The Littlest Rebel, she was Mary for good.

This, in case you’re keeping track, makes the fourth name our girl had by the time she was eleven. Born Juliet Reilly, then Juliet Miles while she lived with her grandmother, then Juliet Shelby after joining her mother in New York, and finally Mary Miles Minter, a name and identity borrowed — stolen, really — from a dead cousin she never knew, yanking her once and for all out of any chance at a normal childhood. I leave the psychiatrists to speculate on what a history like that can do to a girl’s self-image.

By the time she returned to pictures in 1915, this time on the West Coast for a succession of studios, she was an established stage name (although in true Hollywood fashion, her biggest stage hit, The Littlest Rebel, was filmed with somebody else, one Mimi Yvonne). “Of Littlest Rebel fame” followed her everywhere she went.

And so did Charlotte. Somebody made up a nursery rhyme:

And so did Charlotte. Somebody made up a nursery rhyme: Her heart was white as snow.

And everywhere that Mary went,

Her mother had to go.

What effect further work with Taylor might have had we’ll never know, for after the release of Jenny Be Good in April 1920 they never worked together again. But there’s reason to believe — at least judging from Variety’s reviews — that he had a pivotal influence on her acting in those four pictures, all made in the year between her seventeenth and eighteenth birthdays.

He may have had other effects on her as well, and that possibility came to light only after the evening of Wednesday, February 1, 1922. On that night, sometime after 7:45 p.m., in the living room of this bungalow at 404-B Alvarado Street in Los Angeles, somebody stood behind William Desmond Taylor and shot him dead with a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson revolver.

He may have had other effects on her as well, and that possibility came to light only after the evening of Wednesday, February 1, 1922. On that night, sometime after 7:45 p.m., in the living room of this bungalow at 404-B Alvarado Street in Los Angeles, somebody stood behind William Desmond Taylor and shot him dead with a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson revolver.

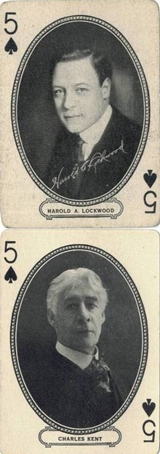

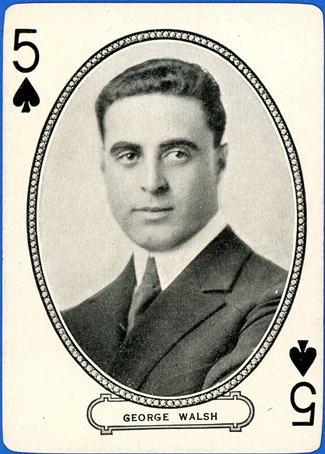

Movie Playing Cards: 5 of Spades – George Walsh

But back to our subject. Born in 1889, George Frederick Walsh followed his older brother Raoul (né Albert Edward) into pictures in the mid-1910s, having originally planned to be an attorney (he attended, however briefly, Fordham and Georgetown). He also attended New York’s High School of Commerce, where he graduated in 1911, and where he was a versatile athlete: baseball, track, cross country, swimming, rowing. This experience would stand him in good stead, at least in the Hollywood short run — certainly better than whatever he learned about commerce or pre-law.

But back to our subject. Born in 1889, George Frederick Walsh followed his older brother Raoul (né Albert Edward) into pictures in the mid-1910s, having originally planned to be an attorney (he attended, however briefly, Fordham and Georgetown). He also attended New York’s High School of Commerce, where he graduated in 1911, and where he was a versatile athlete: baseball, track, cross country, swimming, rowing. This experience would stand him in good stead, at least in the Hollywood short run — certainly better than whatever he learned about commerce or pre-law.

I don’t know what drew George to pictures in the first place, but it’s easy to imagine him being lured by the stories his brother told. Raoul had backed into pictures after working as a cowboy; his horsemanship had landed him a stage job, riding a galloping horse on a treadmill for a touring company of The Clansman. From that he got the acting bug, forgetting all about cowpunching. He wound up in New York making westerns (mostly) for Pathe, then followed D.W. Griffith to California. He loved the freewheeling fun of making pictures in those days, and he surely must have painted an enticing picture for George — “With your looks and athletic ability, you’re a natural for this stuff.” Hal Erickson at AllMovie.com says that George joined Raoul at Reliance-Mutual in 1914, but according to the IMDB, George’s first picture was an indeterminate bit in The Birth of a Nation for D.W. Griffith. Or more likely a series of bits; Griffith was economical in his use of extras, and George may well have been one of those who saw himself on screen fighting on both sides of a battle. Raoul played John Wilkes Booth in Birth, but was already on his way to a director’s career (it would extend to 1964; Raoul Walsh remains a favorite director among critics and historians).

George did get his first breaks in Reliance-Mutual pictures directed by Raoul and others, moving up the cast list till he was top-billed, and first drawing the eye of Variety’s reviewer in Raoul’s Blue Blood and Red (1916): “The kid is clever…a fine, manly looking chap, full of athletic stunts…” By this time, both Raoul and George were working for William Fox, and soon George worked again for D.W. Griffith. Here he is as the Bridegroom of Cana in the Judean Story section of Intolerance, receiving the bad news that the wine supply has run out. With him are 17-year-old Bessie Love (still several years from her own stardom) as the Bride of Cana and William Brown as the father of the bride.

George did get his first breaks in Reliance-Mutual pictures directed by Raoul and others, moving up the cast list till he was top-billed, and first drawing the eye of Variety’s reviewer in Raoul’s Blue Blood and Red (1916): “The kid is clever…a fine, manly looking chap, full of athletic stunts…” By this time, both Raoul and George were working for William Fox, and soon George worked again for D.W. Griffith. Here he is as the Bridegroom of Cana in the Judean Story section of Intolerance, receiving the bad news that the wine supply has run out. With him are 17-year-old Bessie Love (still several years from her own stardom) as the Bride of Cana and William Brown as the father of the bride.

“Walsh is in his glory scaling walls, climbing trees, foiling cops, etc. There are a couple of corking fights where he handles anywhere from a dozen to twenty opponents at a time”; From Now On (’20), “What may be held up for approval is the hard work which George Walsh invests in it.” The image conjured up from these reviews is a series of lightweight adventures distinguished by George’s prowess; as brother Raoul, who directed From Now On, said years later, “Well, anything with him wouldn’t be too heavy.”

“Walsh is in his glory scaling walls, climbing trees, foiling cops, etc. There are a couple of corking fights where he handles anywhere from a dozen to twenty opponents at a time”; From Now On (’20), “What may be held up for approval is the hard work which George Walsh invests in it.” The image conjured up from these reviews is a series of lightweight adventures distinguished by George’s prowess; as brother Raoul, who directed From Now On, said years later, “Well, anything with him wouldn’t be too heavy.” Then came what looked like the break of a lifetime: George Walsh was chosen by writer June Mathis to play the title role in Metro’s screen adaptation of Ben-Hur, to be shot on location in Rome. The role was coveted by every actor in movies except Jackie Coogan. The most popular choice, Rudolph Valentino, was out of play because of a contract dispute with Famous Players-Lasky; until they settled their differences, the studio wasn’t about to let him work for anyone else. Mathis ordered tests, dozens of them, and Walsh won out. In his recounting of the Ben-Hur production in The Parade’s Gone By, Kevin Brownlow tells us that there was little enthusiasm in Hollywood for the choice; George was a fine physical specimen, they all said, but not that strong an actor.

Then came what looked like the break of a lifetime: George Walsh was chosen by writer June Mathis to play the title role in Metro’s screen adaptation of Ben-Hur, to be shot on location in Rome. The role was coveted by every actor in movies except Jackie Coogan. The most popular choice, Rudolph Valentino, was out of play because of a contract dispute with Famous Players-Lasky; until they settled their differences, the studio wasn’t about to let him work for anyone else. Mathis ordered tests, dozens of them, and Walsh won out. In his recounting of the Ben-Hur production in The Parade’s Gone By, Kevin Brownlow tells us that there was little enthusiasm in Hollywood for the choice; George was a fine physical specimen, they all said, but not that strong an actor.Things didn’t go well for Ben-Hur in Italy. Sets weren’t ready, equipment wasn’t available, crews couldn’t speak English, supervisors couldn’t speak Italian. Matters began in a state of disorganization and degenerated into hopeless chaos. June Mathis, ostensibly the production supervisor as well as scriptwriter, was barred from the set by director Charles Brabin — not that there was much set to bar her from. While construction dawdled along, the company adjourned to Anzio to shoot the sea battle; Brabin sat around guzzling wine and regaling the crew with long-winded stories while underlings haggled with local bureaucrats, and hundreds of extras idled sweltering on the beach. When cameras finally rolled, everything went wrong.

Well, I needn’t go on; you can get the whole story from Brownlow. By autumn of 1924, the newly-formed MGM had inherited this mess, and the new bosses, L.B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg, took drastic action. Brabin was fired because his footage was awful. June Mathis was fired because she had been the supposed supervisor of this fiasco, and had insisted on shooting in Rome in the first place. And George Walsh was fired because Mathis had hired him — besides, MGM wanted to build up their rising star Ramon Novarro, and since Walsh hadn’t yet appeared on film it would cost only the price of a ticket home to get rid of him. Walsh and Bushman (who was one of the few survivors of the purge) read about the changes in the newspapers. The whole company — what was left of it — was ordered back to California at once, where Mayer and Thalberg could keep a close eye on things.

It was all a bitter pill for George. “You know, Frank,” he told Bushman, “I felt this was going to happen. But to leave me over here for so long, to let me die in pictures — and then to change me!” Because MGM, in damage-control mode, kept mum about the state of the production and the reasons for such sweeping changes, the impression was left that George simply couldn’t cut it — just as everyone had suspected.

Could he have cut it? Maybe, maybe not. June Mathis shrugged off her own dismissal, saying her chief regret was for Walsh: “I had complete faith in his ability to play Ben-Hur,” she told Photoplay. “I realize many other people did not believe in him, but the same thing occurred when I selected Rudolph Valentino for the role of Julio in The Four Horsemen. Valentino justified himself, and I am confident that Mr. Walsh would have done the same thing. Actually, he was given no opportunity to succeed or fail. He was withdrawn without a chance. Indeed, Mr. Novarro was in Rome for three days before Mr. Walsh was notified that he had been succeeded in the leading role.” Nevertheless, in Hollywood — then as now — image was everything. George slunk home a “failure”, even though he had not faced the cameras for so much as a frame of film.

He didn’t exactly “die in pictures”, but in an age where a star was expected to appear in a new picture several times a year — even every few weeks — George Walsh was off the screen from December 1923 to October ’25. He might as well have moved to Tibet and become a hermit. He had lost momentum, and he never really got it back. His vehicles continued as they had before, with titles like American Pluck, The Kick-Off, Striving for Fortune and His Rise to Fame, but the scripts were more formulaic than ever, the productions cheaper and more slapdash, the companies increasingly fly-by-night. The kid was looking less clever than he once had; more important, he was no longer a kid. His last starring vehicle was the inaptly named Inspiration (1928), which Variety termed “for second run houses in not too particular neighborhoods.”

After the coming of sound Walsh made a few movies, but was never again top-billed. Supporting roles (often in brother Raoul’s pictures like Me and My Gal, The Bowery and Under Pressure) slid into bits — like this one in Cecil B. DeMille’s Cleopatra (1934), as a courier bringing Antony (Henry Wilcoxon) and Cleopatra (Claudette Colbert) the bad news that Octavian is on the march. After Raoul’s Klondike Annie and a couple of Poverty Row westerns in 1936, George decided to call it a day in pictures, and retired from the screen to work as a racehorse trainer for the Hollywood horsey set.

All in all, George Walsh didn’t have such a bad run; his pictures were breezy, undemanding fun in their day and he had a definite following. Getting canned from Ben-Hur was a blow, no doubt, but how much of his subsequent career slide was due to his two years out of circulation, and how much was simply because his day was done, is something I guess we’ll never know. Like any other star, he arrived, he blazed, and he waned, then (unlike some) lived to a ripe old age: George Walsh was 92 when he passed away in Pomona, Calif. in 1981.

Movie Playing Cards: 3 of Hearts – Geraldine Farrar

Geraldine Farrar was not the first star to occupy the M.J. Moriarty deck’s 3 of Hearts; that distinction (if Cliff Aliperti’s guess at the deck’s provenance is correct) belongs to Cleo Madison. But Ms. Farrar is the only Metropolitan Opera star in the deck. Other great singers would make the transition from Met to movies, but not until the sound era; and while some (Lawrence Tibbett, Grace Moore, Lily Pons, Maria Callas) would be more successful than others (Kirsten Flagstad, Luciano Pavarotti), only Geraldine Farrar managed to become a movie star without ever once depending upon her voice to get her there.

No wonder. She was a natural actress without a trace of self-consciousness, and the camera loved loved loved her. The picture on the card isn’t the most flattering, with that hairstyle like a leather aviator’s helmet, but you can see what I mean, especially with those enormous, all-seeing eyes — they make you want to glance over your right shoulder to see what she finds so fascinating and amusing; not even that huge corsage can pull your attention away from her eyes for very long.

Here’s another look at those eyes, this time smoldering and looking straight into your own. The portrait is by the German painter Friedrich August von Kaulbach (1850-1920), and is now part of the Geraldine Farrar Collection in the Music Division of the Library of Congress. It was probably painted in late 1901 or early ’02, about the time the 19-year-old Geraldine created a sensation as Marguerite in Gounod’s Faust and became the toast of Berlin.

Here’s another look at those eyes, this time smoldering and looking straight into your own. The portrait is by the German painter Friedrich August von Kaulbach (1850-1920), and is now part of the Geraldine Farrar Collection in the Music Division of the Library of Congress. It was probably painted in late 1901 or early ’02, about the time the 19-year-old Geraldine created a sensation as Marguerite in Gounod’s Faust and became the toast of Berlin.And then, in 1915, yet another medium. Moving pictures came calling, in the form of Cecil B. DeMille and the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company. Lasky and DeMille had been making a go of their venture out in sleepy Hollywood, shooting in a converted barn at the corner of Vine and Selma Streets. I don’t know what prompted them to approach Farrar; perhaps they read the interview where she described herself not as a singer but “an actress who happens to be appearing in opera” and figured an actress in any other vehicle… Whatever the impetus, it was a masterstroke. Farrar agreed to work eight weeks during the Met’s off season, making three pictures for a fee of $35,000. The news, and the announcement that the diva’s first picture would be a silent version of her Met success Carmen, electrified the industry. The William Fox Co. was inspired to do a quickie knockoff Carmen with their house vamp Theda Bara (Fox’s picture went into release the day after DeMille’s Carmen but doesn’t seem to have cut very deeply into its business).

The DeMille-Lasky Carmen wasn’t planned as an adaptation of the opera; the work was still under copyright, and the proprietors were asking too much for the movie rights. Instead, DeMille and his scriptwriter brother William turned to Prosper Mérimée’s original novella, now in the public domain, which had a story much changed in the opera. Still, the opera was too familiar to ignore completely, so a musical score was commissioned adapting Bizet’s themes (Lasky could afford that much).

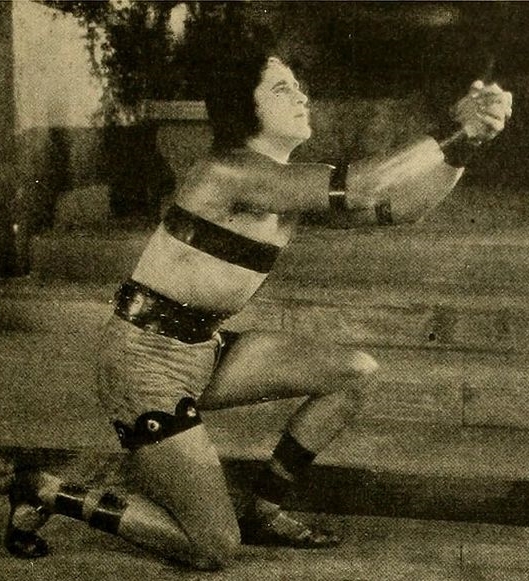

Before shooting on their big-money title, though, DeMille made a canny decision: he would shoot Farrar’s other two pictures (Temptation and Maria Rosa) first, just in case his leading lady needed a little experience to put her at ease in front of the camera. This was probably prudent, but it proved to be unnecessary; Geraldine Farrar took to movies like a duck to water. Here she is in Carmen’s classic pose — a cliché by now, but at that time you could hardly get away with leaving it out — the rose clenched in her teeth, lasciviously eying the unfortunate Don Jose (Wallace Reid), whom she intends to seduce to help her smuggler cohorts.

And here she is again, assuring her gypsy confederate (Horace B. Carpenter) that the trap is ready to be sprung. As DeMille biographer Scott Eyman observes, Farrar wasn’t exactly beautiful, but she was alluring. Her Carmen moves like a cat, slinky, self-assured and radiating a confident, even aggressive sexuality. (Apparently in real life, too; Crown Prince Wilhelm wasn’t the only name linked romantically with hers. While at the Met she carried on a torrid six-year affair with conductor Arturo Toscanini that ended only when she gave him an ultimatum: leave your wife or else. The maestro abruptly resigned from the Met and beat a hasty retreat back to Italy, wife and family in tow.)

And here she is again, assuring her gypsy confederate (Horace B. Carpenter) that the trap is ready to be sprung. As DeMille biographer Scott Eyman observes, Farrar wasn’t exactly beautiful, but she was alluring. Her Carmen moves like a cat, slinky, self-assured and radiating a confident, even aggressive sexuality. (Apparently in real life, too; Crown Prince Wilhelm wasn’t the only name linked romantically with hers. While at the Met she carried on a torrid six-year affair with conductor Arturo Toscanini that ended only when she gave him an ultimatum: leave your wife or else. The maestro abruptly resigned from the Met and beat a hasty retreat back to Italy, wife and family in tow.)

Carmen was a big hit for the Lasky Co., in both money and prestige. Not since the aging Sarah Bernhardt hobbled around on her wooden leg in Queen Elizabeth had a star of such international magnitude graced a movie screen. And it must be said, whatever the Great Sarah’s power on stage, she had hardly a tenth of Farrar’s instinctive understanding of movie acting. By the time the picture was released — on October 31, 1915 — Farrar had returned to the Met; the other pictures she had shot that summer were spaced out for release the rest of the season, Temptation at the end of December and Maria Rosa at the beginning of May 1916.

The Woman God Forgot wasn’t released until 1917; the big money picture for ’16 was Joan the Woman. DeMille and Macpherson drew a direct parallel between the Hundred Years War and the war then raging in Europe, telling the story of Joan’s battle for France within a framing story of an English officer in the trenches of the Great War (also played by Wallace Reid) who takes heart from Joan’s devotion (and attains a similar shall-not-have-died-in-vain martyrdom under the barbed wire). This publicity still was presumably approved for release by DeMille and Lasky, but unfortunately it isn’t terribly becoming to Ms. Farrar; granted, she was some years over-age (and some pounds overweight) for the role, but in the finished picture she never looks quite as tomboy-silly as she does here.

The Woman God Forgot wasn’t released until 1917; the big money picture for ’16 was Joan the Woman. DeMille and Macpherson drew a direct parallel between the Hundred Years War and the war then raging in Europe, telling the story of Joan’s battle for France within a framing story of an English officer in the trenches of the Great War (also played by Wallace Reid) who takes heart from Joan’s devotion (and attains a similar shall-not-have-died-in-vain martyrdom under the barbed wire). This publicity still was presumably approved for release by DeMille and Lasky, but unfortunately it isn’t terribly becoming to Ms. Farrar; granted, she was some years over-age (and some pounds overweight) for the role, but in the finished picture she never looks quite as tomboy-silly as she does here.In fact, it was in working on Joan the Woman that Farrar demonstrated the quality that DeMille, throughout his career, would especially prize among his actors: absolute fearlessness. Well, not absolute; she was actually afraid of horses and had to be doubled in many of her riding scenes. But fearless nevertheless; you can see it in the battle scenes, as she strides resolutely in full armor (only without that dear little pleated skirt) among the flailing swords, maces and pikestaffs.

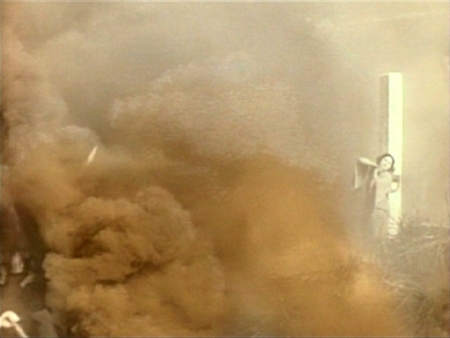

You can particularly see it in the scene of Joan’s execution at the stake, one of the most horrific scenes of the silent era, all the more effective for the stencil-tinting process that colored the flames of her pyre. Looking at a single frame, this closeup might look easy to fake, and it probably would be, but believe me, the flames in action look a lot closer and more dangerous than they do here. But if this shot of Joan appealing to her saints at the moment of death doesn’t convince you Geraldine Farrar was a real game ‘un…

…then how about this?…

…or this?

As Scott Eyman says, “How Farrar managed to survive without third degree burns or, at the very least, smoke inhalation remains a mystery.”

Alas, the honeymoon with Lasky and DeMille did not last, chiefly because of the honeymoon with Lou Tellegen. The Dutch-born Tellegen had come to America in 1910 at 29, as leading man (and offstage consort) to Sarah Bernhardt. After marrying Farrar in 1916, when she returned to Hollywood he began throwing his weight around and interfering in her films. To keep him out of their hair (and hers), DeMille and Lasky allowed him to direct a picture, What Money Can’t Buy. When they judged that one to be a dog — along with another, The Things We Love — Tellegen got his nose bent out of shape, and Farrar (out of what she later ruefully called “wifely loyalty”) sided with him. Both of them left the Lasky Co. and signed with Samuel Goldwyn.

Alas, the honeymoon with Lasky and DeMille did not last, chiefly because of the honeymoon with Lou Tellegen. The Dutch-born Tellegen had come to America in 1910 at 29, as leading man (and offstage consort) to Sarah Bernhardt. After marrying Farrar in 1916, when she returned to Hollywood he began throwing his weight around and interfering in her films. To keep him out of their hair (and hers), DeMille and Lasky allowed him to direct a picture, What Money Can’t Buy. When they judged that one to be a dog — along with another, The Things We Love — Tellegen got his nose bent out of shape, and Farrar (out of what she later ruefully called “wifely loyalty”) sided with him. Both of them left the Lasky Co. and signed with Samuel Goldwyn.

Working her customary off-season shifts, Farrar made six pictures for Goldwyn (three co-starring Tellegen). When Goldwyn complained that her pictures were not doing well, she suggested (with no hard feelings) that they cancel the remaining two years of her contract. She left movies for good in 1920, though she appears to have remained in the M.J. Moriarty deck until it ceased production — perhaps in the hope that she might return to the screen; anyhow, it was back to the Metropolitan Opera, where she retired amid great fanfare in 1922 at the age of 40.

The marriage to Lou Tellegen (her only one, the second of four for him) suffered from his chronic infidelities and succumbed to divorce in 1923. Tellegen himself came to a sorry end in 1934, a month short of his 53rd birthday. By then he had lost his looks (to a combination of age and facial injuries in a fire) and his career. He was ailing (it was cancer, but he wasn’t told). In 1931 he had published an autobiography, Women Have Been Kind, essentially a long boast about his sexual conquests that made him widely despised as a kiss-and-tell cad. (That year, the old Vanity Fair magazine had spotlighted him in their monthly “Nominated for Oblivion” feature, referring to his memoir as Women Have Been Kind [of Dumb].) Now, three years later, he elected himself to the oblivion Vanity Fair had nominated him for: While visiting friends in Hollywood, he locked himself in the bathroom, stood naked before the mirror, stabbed himself seven times with a pair of sewing scissors, and bled to death over an array of his clippings he had strewn on the floor. Approached by a reporter for a comment, Geraldine Farrar said, “Why should that interest me?”

What might have been if Geraldine Farrar had not joined in Lou Tellegen’s falling-out with Cecil B. DeMille is a tantalizing question mark. Even more tantalizing is the thought of how her career might have gone if she’d been born 20 years later, if she had made that hit in Berlin in 1921 instead of 1901. Then, when Hollywood went ransacking New York for musical talent during the sound revolution, she would have been about the age she is here, when she created the role of the Goose-Girl in Humperdinck’s Königskinder (The King’s Children) at the Met in 1910. Jeanette MacDonald and Irene Dunne, among others, may have had reason to be grateful that they never had to deal with any competition frrom Geraldine Farrar.

What might have been if Geraldine Farrar had not joined in Lou Tellegen’s falling-out with Cecil B. DeMille is a tantalizing question mark. Even more tantalizing is the thought of how her career might have gone if she’d been born 20 years later, if she had made that hit in Berlin in 1921 instead of 1901. Then, when Hollywood went ransacking New York for musical talent during the sound revolution, she would have been about the age she is here, when she created the role of the Goose-Girl in Humperdinck’s Königskinder (The King’s Children) at the Met in 1910. Jeanette MacDonald and Irene Dunne, among others, may have had reason to be grateful that they never had to deal with any competition frrom Geraldine Farrar.