Picture Show 2022 – Day 2

Day 2 of The Columbus Moving Picture Show began — after Chapters 4-6 of Adventures of Red Ryder, of course — with another happy holdover from Cinevent, one which dates back at least to 2001: the Festival of Charley Chase Shorts.

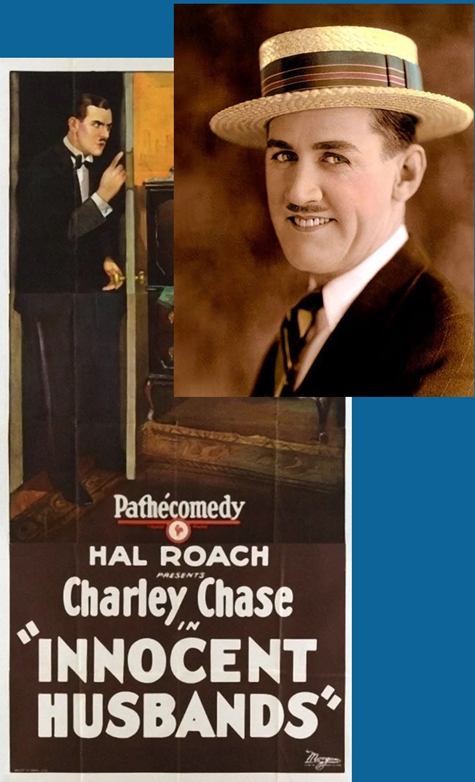

Charley Chase: cheerful, dapper, handsome, doggedly normal, even ordinary, yet constantly put-upon and buffeted by events not of his making; for nearly 20 years it was a winning screen persona for the man born Charles Joseph Parrott in 1893. By now Charley needs no introduction to Cinevent/Picture Show regulars, but there may be Cinedrome readers who are still unfamiliar with him. Unlike every other great silent clown — Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, Langdon, Laurel and Hardy, even Roscoe Arbuckle before his murder trials scuttled his career — Charley Chase never moved up to features, other than the occasional supporting role for friends, as in Laurel and Hardy’s Sons of the Desert (1933). But he made hundreds of one- and two-reel shorts between 1914 and 1940, hitting his stride in the 1920s for Hal Roach. When Roach himself began concentrating on features and moving away from shorts, he dumped Chase in 1936, whereupon Charley moved over to Columbia, where he both acted in shorts and directed them, sometimes under his real name (more about that later today). Maybe Chase felt temperamentally unsuited to features, or maybe he was just behind the curve and would have made the leap eventually. We’ll never know because he drank himself to death in 1940 at 46, and his life and work, once quite popular, went down the memory hole.

Fortunately, interest in Charley Chase has been on the upswing since the 1990s (witness the Cinevent tributes appearing in 2001 and thereafter), and it’s much easier to find him than in the first decades after his death. There’s a Web site, The World of Charley Chase, with a lot of good information, although it appears not to have been updated since 2019. And anyone wishing to sample Charley’s work will find plenty to choose from on Amazon and YouTube. On Amazon I particularly recommend the series Charley Chase: At Hal Roach: The Talkies from The Sprocket Vault and Kit Parker Films — three volumes so far, with a fourth coming in October.

In recent years the Cinevent emphasis has been on Chase’s silent shorts, and so it was this year at The Picture Show. There were three in all:

Innocent Husbands (1925) Faithful husband Charley flies into a panic when a drunk woman from a party next door passes out in his apartment — and jealous wifey (Katherine Grant) is due home any minute.

Dog Shy (1926) Charley, who has a serious phobia about dogs, tries to help a female friend from college escape from an arranged marriage to a pompous duke. His efforts are frustrated by the presence of her family’s enormous dog — also, curiously, named Duke.

Limousine Love (1928) Already late for his wedding, Charley is delayed even further when a naked lady takes refuge in the back seat of his limo (don’t ask). A passerby, hearing Charley’s predicament, offers to help — he doesn’t know, and neither does Charley, that Charley’s nude passenger is his wife.

The day’s first feature was Ramrod (1947), introduced by James D’Arc. James, in addition to being a film historian, is a professor emeritus at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, and the author of When Hollywood Came to Utah, the title of which is pretty self-explanatory. If you’ve ever visited or driven through the Beehive State, you know the beauty of its scenery — there’s much more to it than just the Great Salt Desert. Hollywood has indeed come there to work. You might be surprised to learn how many movies have been shot there, many of them drawn to the terrible, majestic desolation of Monument Valley.

The day’s first feature was Ramrod (1947), introduced by James D’Arc. James, in addition to being a film historian, is a professor emeritus at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, and the author of When Hollywood Came to Utah, the title of which is pretty self-explanatory. If you’ve ever visited or driven through the Beehive State, you know the beauty of its scenery — there’s much more to it than just the Great Salt Desert. Hollywood has indeed come there to work. You might be surprised to learn how many movies have been shot there, many of them drawn to the terrible, majestic desolation of Monument Valley.

But not all. Ramrod was one that passed on Monument Valley in favor of Zion National Park and the ghost town of Grafton just south of the park. Wikipedia even claims that Ramrod‘s producer Harry Sherman actually purchased Grafton to use as a filming location, but I was able to find no confirmation of this in James D’Arc’s book, so…well, Wikipedia, you know. Still, no denying that Sherman, “a westerner at heart” in James’s words, was taken with Utah in general and Grafton in particular.

Like Pursued (1947) at last year’s Cinevent, Ramrod is a western with overtones of film noir. If anything, in Ramrod the overtones are even more pronounced; among them being the inclusion of a femme fatale played by Veronica Lake, then-wife of director Andre de Toth (this was their first project together). Check out the slogan on this poster about men being so easy; other posters were even more provocative: “They called it God’s Country…until the Devil put this woman there!” Both catchphrases aptly summarize Connie Dickason, Lake’s character — although, seeing as how the movie takes place sometime in the 1880s, I don’t recall her ever showing as much leg or décolletage as she does on this poster. In fact, I don’t think we saw so much as an ankle.

But this femme was plenty fatale, make no mistake. Ruthless, duplicitous and manipulative, she plays all the men around her against each other to make a go of her cattle empire: her ranch foreman, or “ramrod” (Joel McCrea); her decent weakling of a father (Charlie Ruggles); a good-bad-man drifter (Don DeFore); a rival rancher and former suitor (Preston Foster); the local sheriff (Donald Crisp); and various bystanders who become collateral damage in her drive to prevail. Her conniving is so over the top that at the film’s dénouement (which I will not spoil here), more than a few satisfied chuckles rippled through The Picture Show screening room. This may well be Veronica Lake’s best performance. Her director husband de Toth deserves credit, too, for effectively disguising the fact that at 5 ft. 1 in., she’s at least a foot or more shorter than all the men she uses, bullies and domineers.

Moving on, to after the lunch break…

In 1936 Paramount released a picture entitled Valiant Is the Word for Carrie, in which Gladys George played a prostitute who reforms for the sake of two orphans and starts a successful laundry business, only to have heartache beset her and the orphans as the children grow to adulthood, with (to paraphrase Thelma Ritter in All About Eve) everything but the bloodhounds snapping at their rear ends. It was a shameless six-hanky tearjerker and a big hit; Gladys George was nominated for an Academy Award. That was then. Now, Valiant Is the Word for Carrie is as utterly forgotten as any major Hollywood A-picture of the sound era. Gladys George lost her Oscar bid to Luise Rainer in The Great Ziegfeld, and she’s mainly remembered now as Miles Archer’s cheating wife in The Maltese Falcon (1941) and the woman who says, “He used to be a big shot” about James Cagney at the end of The Roaring ’20s (1939).

If you think I’m building up to telling you that Valiant Is the Word for Carrie was screened at this year’s Picture Show, I’m not. I’m setting up one of the most exquisitely hilarious jokes in movie history, one that everyone understood at the time, but which nobody gets anymore. It so happens that the following year, the Three Stooges came out with one of their best-remembered shorts. It’s still very popular, but its most brilliant joke, which goes over the head of every Stooges fan today, is its title: Violent Is the Word for Curly (1937).

If you think I’m building up to telling you that Valiant Is the Word for Carrie was screened at this year’s Picture Show, I’m not. I’m setting up one of the most exquisitely hilarious jokes in movie history, one that everyone understood at the time, but which nobody gets anymore. It so happens that the following year, the Three Stooges came out with one of their best-remembered shorts. It’s still very popular, but its most brilliant joke, which goes over the head of every Stooges fan today, is its title: Violent Is the Word for Curly (1937).

And how’s this for a coincidence: This classic Stooges short was directed by none other than our good friend Charley Chase, returning to the Picture Show screening room with only lunch and Ramrod between his last appearance and this. The academic robes in this shot are because Moe, Larry and Curly play gas station attendants who — never mind why — find themselves mistaken for three distinguished professors newly hired at a women’s college. The company of so many beautiful young co-eds is all it takes for the three of them to decide to go along with the mistake, and their introduction to the student body (if you’ll pardon the expression) leads to one of the Stooges’ most famous bits, one they performed live at personal appearances for years afterwards. This is the song “Swingin’ the Alphabet”, interpolated here by Charley, who learned it from his family maid. Stewart McKissick’s program notes tell us that the song itself was the work of the 19th century songwriter Septimus Winner (“Listen to the Mockingbird”, “Ten Little Indians”). Maybe so, but as done by the Stooges it definitely has a 1930s swingtime rollick to it. The whole short can be seen on YouTube, and here’s just the song — rather nicely colorized.

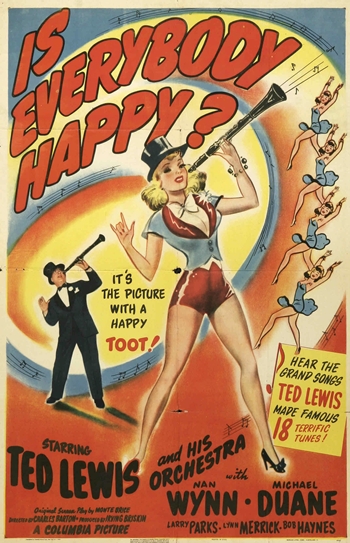

The title of Is Everybody Happy? (1943) was the trademarked catchphrase of bandleader Ted Lewis, who was a household name second only to Paul Whiteman in the 1920s, well before the advent of what we know as the Big Band Era, and would remain so well into the ’60s. He was an indifferent musician (his instrument was the clarinet) and a vocalist with a range of approximately one note, but his schmaltzy personality struck a chord with ballroom and radio audiences and he was a popular front man, especially since the band he fronted was so very good (indifferent clarinetist or no, he knew talent when he hired it, and his band was an early stop for such future greats as Benny Goodman, Jimmy Dorsey, Muggsy Spanier and Jack Teagarden).

The title of Is Everybody Happy? (1943) was the trademarked catchphrase of bandleader Ted Lewis, who was a household name second only to Paul Whiteman in the 1920s, well before the advent of what we know as the Big Band Era, and would remain so well into the ’60s. He was an indifferent musician (his instrument was the clarinet) and a vocalist with a range of approximately one note, but his schmaltzy personality struck a chord with ballroom and radio audiences and he was a popular front man, especially since the band he fronted was so very good (indifferent clarinetist or no, he knew talent when he hired it, and his band was an early stop for such future greats as Benny Goodman, Jimmy Dorsey, Muggsy Spanier and Jack Teagarden).

Lewis’s lilting, wistful refrain between songs of “Is EVVVV’rybody HAPPP…pyyyy…?” was so instantly recognizable and widely imitated that it had already served as the title for his first film musical in 1929. That had been a bit of a train wreck and was completely forgotten by the time Columbia used the title 14 years later for this B-picture, an early specimen of what would come to be known as the jukebox musical. That “18 terrific tunes!” on this poster was no exaggeration; the songs, all easily sing-along-able chestnuts for 1943 audiences, included “Am I Blue?”, “Cuddle Up a Little Closer”, “St. Louis Blues”, “When My Baby Smiles at Me”, and (as the saying goes) many more. With a running time of only 74 min., the music never stopped for long. A good thing, too.

The last feature before dinner was the earliest of the whole weekend: Happiness (1917). It was, as Variety pointed out in its review on May 4 of that year, essentially a “poor little rich girl” picture, with Enid Bennett as a super-wealthy and super-shy heiress who gets a reputation for snobbery thanks to a snarky profile in a newspaper magazine supplement. When she goes away to college, eager to make friends, she finds that her bogus “reputation” precedes her and everybody shuns her — except for one decent fellow (Charles Gunn) working his way through college by taking in laundry. It was a diverting little drama, but the most remarkable thing about it is its basic premise: A perfectly nice person who wouldn’t harm anybody finds her life (almost) ruined by some nasty reporter for no better reason than to sell newspapers. That this plot device could be employed without even raising an eyebrow more than a hundred years ago suggests that contempt and mistrust for a dishonest, yellow-journalism news media isn’t as recent a phenomenon as we might think.

The last feature before dinner was the earliest of the whole weekend: Happiness (1917). It was, as Variety pointed out in its review on May 4 of that year, essentially a “poor little rich girl” picture, with Enid Bennett as a super-wealthy and super-shy heiress who gets a reputation for snobbery thanks to a snarky profile in a newspaper magazine supplement. When she goes away to college, eager to make friends, she finds that her bogus “reputation” precedes her and everybody shuns her — except for one decent fellow (Charles Gunn) working his way through college by taking in laundry. It was a diverting little drama, but the most remarkable thing about it is its basic premise: A perfectly nice person who wouldn’t harm anybody finds her life (almost) ruined by some nasty reporter for no better reason than to sell newspapers. That this plot device could be employed without even raising an eyebrow more than a hundred years ago suggests that contempt and mistrust for a dishonest, yellow-journalism news media isn’t as recent a phenomenon as we might think.

After the dinner break we leapt forward 98 years, from the earliest movie at The Picture Show to the most recent. This was Bride of Finklestein (2015) — not only the most recent film of the weekend, but “younger” than anything ever shows at Cinevent during it’s 52-year run. But while it may have come into being only seven years ago, in content, style and spirit it’s much older — say, somewhere between 1935 and 1940.

After the dinner break we leapt forward 98 years, from the earliest movie at The Picture Show to the most recent. This was Bride of Finklestein (2015) — not only the most recent film of the weekend, but “younger” than anything ever shows at Cinevent during it’s 52-year run. But while it may have come into being only seven years ago, in content, style and spirit it’s much older — say, somewhere between 1935 and 1940.

Let me explain. Bride of Finklestein is one of the extant comedy shorts of Benny Biffle and Sam Shooster. Biffle and Shooster, in turn, are the creations of Nick Santa Maria (Biffle, left), Will Ryan (Shooster, right), and their producer-director Michael Schlesinger (not pictured, but a veteran contributor to past Cinevents). Together they made a number of Biffle and Shooster shorts between 2013 and 2015, faithfully duplicating the black-and-white style of such classic comedy teams as Laurel and Hardy, Abbott and Costello, and Wheeler and Woolsey, with titles like It’s a Frame-Up!, Imitation of Wife, and Schmo Boat (that last one a musical in a pretty faithful approximation of Cinecolor). On the strength of just Bride of Finklestein, I can testify that Biffle and Shooster can hold their own among those classic teams, and are much funnier than Wheeler and Woolsey (but then, root canals are funnier than Wheeler and Woolsey). There are two Biffle and Shooster collections available that I know of: The Adventures of Biffle and Shooster can be streamed on Amazon Prime. There is also a DVD, The Misadventures of Biffle and Shooster; which has everything on the streaming Adventures, plus 28 minutes of other odds and ends; the DVD can be obtained from Amazon (curiously, the DVD is a Kino Lorber release, but the KL Web site offers only the shorter Adventures). Sadly, what we have now of Biffle and Shooster is all we’ll ever get: Will (“Sam Shooster”) Ryan passed away in November 2021; The Picture Show’s screening of Bride of Finklestein, introduced by Michael Schlesinger, was dedicated to his memory.

Bride of Finklestein also served as a kind of lead-in to the next feature, which was introduced by Nick (“Benny Biffle”) Santa Maria. This was Hold That Ghost (1941), Abbott and Costello’s third starring feature, and one of their best. It started out as a B-comedy, Oh, Charlie, produced before their previous vehicle, Buck Privates, was released. When Buck Privates became Universal’s biggest hit in years and Universal finally realized what they had in Bud and Lou, Oh, Charlie was held back while they rushed the team into another service comedy, In the Navy. Meanwhile, Oh, Charlie was pumped up to A-picture status by adding musical numbers with the Andrews Sisters (who supported Bud and Lou in both service pictures) and (once again!) Ted Lewis. Retitled Hold That Ghost, it was released on August 30, the third of their four pictures for 1941.

Bride of Finklestein also served as a kind of lead-in to the next feature, which was introduced by Nick (“Benny Biffle”) Santa Maria. This was Hold That Ghost (1941), Abbott and Costello’s third starring feature, and one of their best. It started out as a B-comedy, Oh, Charlie, produced before their previous vehicle, Buck Privates, was released. When Buck Privates became Universal’s biggest hit in years and Universal finally realized what they had in Bud and Lou, Oh, Charlie was held back while they rushed the team into another service comedy, In the Navy. Meanwhile, Oh, Charlie was pumped up to A-picture status by adding musical numbers with the Andrews Sisters (who supported Bud and Lou in both service pictures) and (once again!) Ted Lewis. Retitled Hold That Ghost, it was released on August 30, the third of their four pictures for 1941.

Personally, I still say the team’s masterpiece is Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948); after that, my own favorite is The Time of Their Lives (’46), with Lou and Marjorie Reynolds as ghosts from the American Revolution haunting modern-day Bud. Hold That Ghost, which has Bud and Lou treasure-hunting in a supposedly haunted old tavern they’ve inherited from a dead gangster, is right up there with them, funny enough to make the tacked-on musical numbers worth sitting through. Funniest scene: a levitating candle that scares the wits out of Lou but refuses to budge when Bud is looking. Pleasant surprise: Joan Davis as a radio actress who specializes in screams; she’s a scream herself, as funny as Lou.

Next to the 1930s pastiche of Bride of Finklestein, the most recent picture at The Picture Show this year was Sail a Crooked Ship (1961), a lumpy, slipshod caper comedy that had Robert Wagner as the naïve nephew of a Boston scrap-metal dealer who tries to save a mothballed Liberty Ship from the scrap heap, only to see it, himself, and his long-suffering fiancée (Dolores Hart) fall into the hands of a gang with big plans and small I.Q.s. The gang plans to use the ship as their getaway vehicle after knocking over a Boston bank disguised as Pilgrims during a Thanksgiving festival. It was an inoffensive time-waster, interesting mainly as the last film of TV comedy genius Ernie Kovacs; it was released barely three weeks before he wrapped his Corvair station wagon around a lamppost on Santa Monica Blvd., dying instantly. His performance, indeed, was one of the picture’s assets, as was that of Frank Gorshin as the (relatively speaking) “brains” of the gang.

Not long after Sail a Crooked Ship, Dolores Hart gave up acting and became a nun. Coincidence? Maybe.

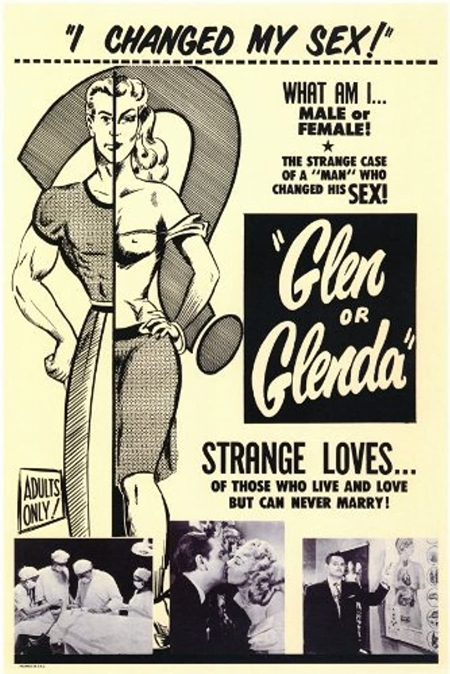

Day 2 wrapped up with Glen or Glenda (1953), the notorious first film by the notorious Edward D. Wood Jr. This poster notwithstanding, Glen or Glenda was not entirely about transgenderism — or, as it was more commonly known at the time, a “sex-change operation”. To be sure, that was what producer George Weiss had in mind when he hired Wood to write and direct a quickie picture exploiting the case of Christine Jorgensen (née George), whose series of gender-reassignment surgeries between 1951 and 1953 had focused public awareness on the issue; Weiss wanted to cash in.

Day 2 wrapped up with Glen or Glenda (1953), the notorious first film by the notorious Edward D. Wood Jr. This poster notwithstanding, Glen or Glenda was not entirely about transgenderism — or, as it was more commonly known at the time, a “sex-change operation”. To be sure, that was what producer George Weiss had in mind when he hired Wood to write and direct a quickie picture exploiting the case of Christine Jorgensen (née George), whose series of gender-reassignment surgeries between 1951 and 1953 had focused public awareness on the issue; Weiss wanted to cash in.

Shooting in four days, Wood gave Weiss what he asked for — sort of. In fact, Glen or Glenda divides its time between two cases, both recounted by a doctor to a police detective (Lyle Talbot) investigating the suicide of a man who, repeatedly arrested for wearing women’s clothes, couldn’t face going through the ordeal again. As the doctor describes the two cases, one is Glen/Glenda, a “transvestite” — a heterosexual man who finds it pleasurable and comfortable to wear women’s clothes — while the other is Alan/Anne, a “transsexual” — a person who feels mentally and emotionally female but is trapped in a male body. Whether the movie’s approach to the issue would pass muster with 21st-century gender theory is beside the point; what matters is that it was surprisingly enlightened for 1953 (there were some pretty mean jokes going around about Christine Jorgensen at the time), and it offered an earnest plea for compassion and understanding. Note I said “earnest”, not “eloquent”. The fact is that, whatever its intentions, Glen or Glenda comes up against the invincible ineptitude of Edward D. Wood Jr.

What can we say about Ed Wood? The kindest thing is that you have to be in a certain frame of mind to sit through one of his movies. Tim Burton’s 1994 biopic Ed Wood tried to portray him (in the person of Johnny Depp) as a wide-eyed naif with an irresistible urge to be part of the transformative art of the twentieth century, moving pictures. Burton’s movie got good reviews, and won an Oscar for Martin Landau playing Bela Lugosi (whom Wood befriended and exploited in Lugosi’s last drug-riddled years), but it sank like a rock at the box office, earning less than a third of its modest $18 million cost. My own feeling was that if you wanted to make a movie celebrating some unsung artist of the motion picture industry, there were about 875 directors you might go through before you got down to Ed Wood.

Nevertheless, any Ed Wood movie is certainly something to have seen, and Glen or Glenda is less mind-bogglingly inept than his later movies like Bride of the Monster and Plan 9 from Outer Space — probably because he wasn’t yet the incoherent, falling-down drunk he would later become. Even so, as a writer he could barely put one sentence after another; Glen or Glenda‘s narrative is interrupted at intervals by Bela Lugosi sitting in a laboratory among skeletons, skulls and test tubes, babbling about God knows what. As a director he lacked any sense of pace, composition or atmosphere. And as an actor — Wood, himself a heterosexual cross-dresser, plays Glen/Glenda, billed as “Daniel Davis” — as an actor he was…well, any junior high drama club in the country would have been glad to have him.

As I said, something to have seen, and you can see it here on YouTube. And with that, we called it a day in Columbus. More to come!