Minority Opinion: The Magnificent Ambersons, Part 1

It happens to be my personal opinion that Citizen Kane is Orson Welles’s second greatest movie; I prefer The Magnificent Ambersons, and by a considerable margin. Maybe it’s because I first discovered Ambersons on late-night TV in the early 1960s, a good four years before I first saw Kane. I hadn’t yet heard all the tales and legends behind the making (and editing) of the picture, so I didn’t know I was supposed to regard it with sorrowful disdain as The Great Saint Orson’s might-have-been masterpiece yanked from his loving hands and mutilated by the mindless paws of lesser, crasser men. All I knew was what I saw on the screen, and I thought it was a terrific movie. I still do.

It happens to be my personal opinion that Citizen Kane is Orson Welles’s second greatest movie; I prefer The Magnificent Ambersons, and by a considerable margin. Maybe it’s because I first discovered Ambersons on late-night TV in the early 1960s, a good four years before I first saw Kane. I hadn’t yet heard all the tales and legends behind the making (and editing) of the picture, so I didn’t know I was supposed to regard it with sorrowful disdain as The Great Saint Orson’s might-have-been masterpiece yanked from his loving hands and mutilated by the mindless paws of lesser, crasser men. All I knew was what I saw on the screen, and I thought it was a terrific movie. I still do.

It’s not my purpose here to try to dethrone Kane in favor of Ambersons; that’s a fool’s errand and I know it. Everybody who considers Citizen Kane the greatest movie ever made — i.e., just about everybody with an opinion on the subject — has good and sufficient reasons for saying so, and I wouldn’t dream of trying to talk them out of it. Personally, I’ve always found Kane … well,dazzling, impressive, virtuosic and all that, certainly, and a singular achievement any way you cut it. But for me it’s a rather cold movie that I rather coldly admire, like a display of fireworks seen from afar.

In Ambersons the fireworks are much closer and consequently quieter — and they’re very personal. The Magnificent Ambersons was a very personal picture for Orson Welles, too; quite a bit more personal, I think, than Citizen Kane had been. And I suspect that’s why he took what happened to Ambersons so personally; his bitterness was palpable any time the title was mentioned during the last 43 years of his life. “They destroyed Ambersons,” he often said, “and the picture destroyed me.”

Pardon me, but nobody destroyed The Magnificent Ambersons. If the picture is not as great as it might have been — and I do not concede that point — I say Orson Welles deserves as much blame for it as anyone. I suspect that on some level he knew that, and I think his bitterness over it must have come from chagrin as much as righteous indignation — maybe more.

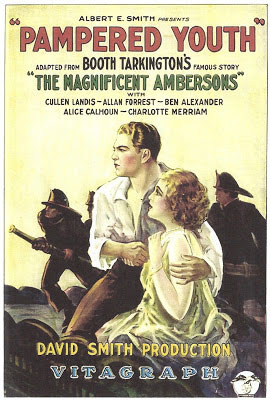

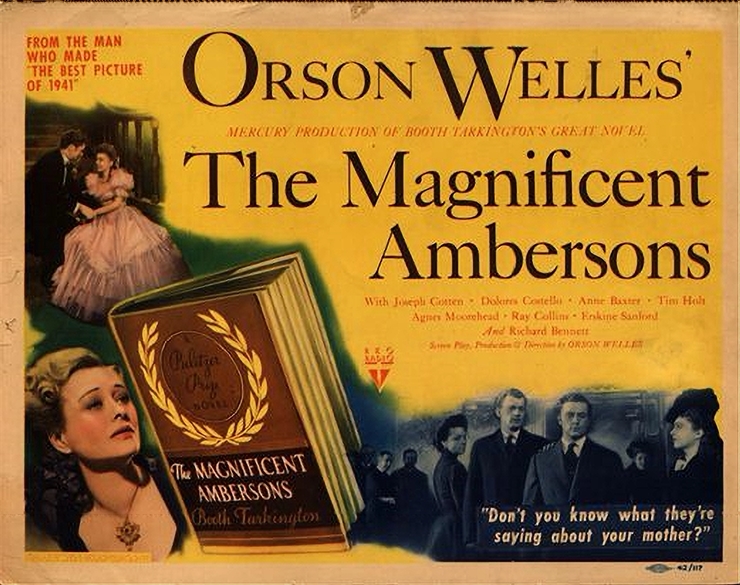

The Magnificent Ambersons, first of all, was a novel that won author Booth Tarkington the first of his two Pulitzer Prizes (the second came three years later for Alice Adams). Born in 1869 in Indianapolis, Tarkington was successful right out of the chute with his first novel, The Gentleman from Indiana, published when he was 30. He was popular and prolific, turning out some 53 novels, plays and nonfiction books, including one published posthumously in 1947. Like many of his contemporaries, he has drifted out of fashion, but in his day he was nationally famous and well respected; his Penrod books, idealized yarns of mischievous childhood, gave Mark Twain’s Tom and Huck a good run for their money, and in 1922 the Literary Digest proclaimed him “America’s greatest living writer”.

The Magnificent Ambersons, first of all, was a novel that won author Booth Tarkington the first of his two Pulitzer Prizes (the second came three years later for Alice Adams). Born in 1869 in Indianapolis, Tarkington was successful right out of the chute with his first novel, The Gentleman from Indiana, published when he was 30. He was popular and prolific, turning out some 53 novels, plays and nonfiction books, including one published posthumously in 1947. Like many of his contemporaries, he has drifted out of fashion, but in his day he was nationally famous and well respected; his Penrod books, idealized yarns of mischievous childhood, gave Mark Twain’s Tom and Huck a good run for their money, and in 1922 the Literary Digest proclaimed him “America’s greatest living writer”.Tarkington’s current obscurity is undeserved. Certainly his two Pulitzer Prize winners are as good as they ever were. The Magnificent Ambersons was the middle volume of a trilogy Tarkington called Growth (the others: The Turmoil [’15] and The Midlander [’24]), and is the only one of the three that remains in print.

Magnificence, Tarkington writes, is always comparative; the magnificence of the Ambersons dated from 1873, when Major Amberson made his fortune, and it lasted “throughout all the years that saw their Midland town spread and darken into a city”. The Ambersons and their doings dominate the town’s activities and its conversations; everybody knows what they are up to and cares what they say, think and do. Major Amberson has six offspring, but only three of them figure in Tarkington’s plot: sons George and Sydney and daughter Isabel. Isabel in turn has two suitors: careful, quiet Wilbur Minafer (“a steady young businessman and a good church-goer”) and George’s best friend Eugene Morgan — dashing, charming, and a little wild.

One night, Eugene gets a bit too wild. In a state of inebriation while trying to serenade Isabel, he stumbles through a bass viol, reducing it to splinters and himself to a mumbling heap. Humiliated by his “making a clown of himself in her front yard”, Isabel refuses to accept his apologies or even to see him, and two weeks later announces her engagement to Wilbur. The wedding is a grand Amberson affair, the honeymoon as staid and careful as the groom, and Wilbur and Isabel move into their new house, a wedding present from the Major next door to (and almost as impressive as) his own, and they live there with Wilbur’s unmarried sister Fanny.

Isabel is a good and faithful wife to Wilbur, but she doesn’t really love him. A town dowager predicts that all her love will go to their children, “and she’ll ruin ’em.” The dowager is only partly wrong: Wilbur and Isabel don’t have children, they have one child.

By the time he is ten years old, George Amberson Minafer, the Major’s only grandchild and the apple of his adoring mother’s eye, is a spoiled rotten brat, lording it over local citizens and strutting around town as if he owns the whole place — which he assumes, by right of birth, he will someday. As a teenager he high-hats and bullies his supposed friends in a “secret club” they have formed when they dare to elect someone else president. The idea that he may be making enemies never enters Georgie’s mind; it’s other people’s job to curry favor with him. He dismisses anyone not an Amberson as “riffraff”. Among the solid citizens of the town, more than a few long for the day this haughty young prince will get his “comeuppance” (“Something was bound to take him down, some day, and they only wanted to be there!”).

So much for prologue. The Magnificent Ambersons really begins when 19-year-old George Minafer, now grown into a strikingly handsome young man, comes home from school for the Christmas holiday. His parents and grandfather host an elaborate formal soiree in his honor at the Major’s mansion. It is “the last of the great long-remembered dances that ‘everybody talked about'” — because, although the Ambersons may not realize it, their town is already growing too large for “everybody” to talk about anything.

At this party George comports himself according to his idea of noblesse oblige, pretending to remember people when he doesn’t (and, with some of his former boyhood friends, pretending he doesn’t know them when he does). One of the people he pretends to remember is none other than Eugene Morgan, now a widower with an 18-year-old daughter, returning to town for the first time since before George was born. George doesn’t know the history between his mother and Eugene, of course, but there’s something about the man that he doesn’t quite like.

Eugene’s daughter Lucy, however, is another matter. George likes her very much; he is instantly smitten. Lucy, for her part, takes a liking to him as well, despite his rather smug and grandiose airs, which, to his consternation, she finds slightly amusing.

Eugene spends the evening dancing with Isabel and with George’s Aunt Fanny and talking over old times with Uncle George, the Major, and his old rival Wilbur. Fanny — who, like many young women back in the day, was quite taken with Eugene — revels in his return, and in a quieter way, so does Isabel.

George stifles his mild dislike for Eugene as he continues to court Lucy, never quite sure where he stands with her, but finding her so much more interesting than the “silly” girls he grew up with. Eugene, meanwhile, becomes a regular visitor in the Minafer home, taking Fanny and Isabel, and sometimes Uncle George, on frequent outings in his automobile. For all of them it seems like old times, which both amuses and unsettles young George.

Some time later, the first crack in Major Amberson’s vast fortune appears when Uncle Sydney and his wife Amelia — insufferable snobs — decide that the town isn’t fit for a “gentleman” to live in, and pressure the Major to give them their share of his estate now rather than make them wait to inherit it in his will. Uncle George holds that the estate can’t handle being broken up so soon, and in the ensuing squabble Amelia makes catty allusions to rumors going around about Eugene and Isabel. Young George, his latent antipathy aroused, is alarmed, but Aunt Fanny, herself infatuated with Morgan, pooh-poohs the idea, while Uncle George dismisses it as the idle gabble of the malicious and greedy Amelia.

During young George’s senior year at college, Wilbur Minafer dies, the victim of a listless constitution and his worries about a business that died just before he did, taking all the Minafer money with it. Wilbur’s death therefore leaves Fanny penniless and at the mercy of her Amberson in-laws. Isabel and George agree that Fanny should continue to live with them, and they assign Wilbur’s life insurance money to her to give her something of a nest-egg. Still, she remains bereft, insecure and emotionally fragile; when Georgie returns home after graduation and teases her anew about Eugene Morgan, she is quickly driven to tears.

Also on his return from college, George is appalled to discover that the broad lawn between the Amberson Mansion and his and Isabel’s house has been subdivided by the Major to build five smaller houses as rental properties. George’s aesthetic sensibilities are offended; even more offensive is the idea of strangers — riffraff — interloping on Amberson property. Uncle George fails to impress on his nephew the idea that perhaps the Major needs the money. Later, when George asks his grandfather to buy a larger two-horse carriage, or even a four-in-hand, the Major temporizes, then mumbles something about helping George get through law school. George fails to make the obvious connection; he worries that the Major is getting senile.

Eugene Morgan continues a frequent visitor at the Amberson and Minafer homes, taking Isabel and Fanny — sometimes the Major, or Uncle George, or young George too, but always Isabel — for drives in his motorcar. Georgie, for his part, prefers buggy rides with Lucy, but his courtship is not going well. Whenever he presses her to become engaged, she sadly parries his advances. Finally George gets her to admit that she is concerned for her father’s approval and uneasy about George’s reluctance to “make something of himself”. George is affronted; why should he make something of himself when he’s already an Amberson? The very suggestion that he enter some profession insults him. He becomes quarrelsome, and he and Lucy are estranged.

That same evening, on their front porch, as Fanny and Isabel chat, George daydreams of Lucy begging his forgiveness, promising she will never listen to her father again, that she now dislikes him just as much as George does. This is followed by another, less pleasant fantasy: He imagines Lucy surrounded by young men — the same ones he bullied and dominated when they were boys — and laughing gaily, giving no thought to him. Riffraff! George continues to stew over his foundering romance with Lucy, and what he sees as Eugene’s meddling in his personal life. (Everything is always about George Amberson Minafer.)

One night, when Eugene comes to dinner — without Lucy — George’s resentment boils over. As Eugene and the Major chat about Eugene’s flourishing automobile factory, George blurts out that automobiles are a useless nuisance; they’ll never amount to anything and had no business being invented. In the awkward silence that follows, the Major chides George for his tactlessness. Eugene’s answer is worth quoting because it has become — partly due to the abbreviated version of it that appears in Orson Welles’s movie — the most famous passage from the novel:

Some time later, when George, still brooding over his break with Lucy, again snubs Eugene, Fanny sees it and comes to George’s room to congratulate him. She knows exactly what he’s doing, she says, but she doesn’t. In fact, she has let her own frustrated dreams of marrying Eugene Morgan poison her, and the poison festers as she sees long-buried feelings blossoming again between Eugene and Isabel. Now, misunderstanding George’s motives, she says she understands that he’s only trying to protect his mother’s reputation, that he’d give up Lucy in a minute if it was a matter of Isabel’s good name.

George is thunderstruck. In his self-absorption he hasn’t given a thought to Eugene and Isabel, but now, badgering the sputtering Fanny, he learns that Aunt Amelia was right, there has been talk about them, and it has only increased since Wilbur’s death. Fanny thought he already knew, but in fact she’s the one who has told him. Now she tries to restrain him, but he flies into a fury.

George storms across the street to confront Fanny’s friend Mrs. Johnson, a notorious gossip. Imperious as always, he demands to know who has been slandering his mother’s name, but she indignantly orders him out of her house. When George turns to his uncle, Uncle George is appalled at what George has done. Doesn’t he realize that he’s only thrown fuel on the fire? Gossip is never fatal until it’s denied, he says. Worse yet, in his nephew’s eyes, he appears unperturbed at the thought of Eugene and Isabel marrying; why shouldn’t they, he says, if they’re both free and care about each other? Young George calls the idea “monstrous”.

It is clear to Georgie that it’s up to him to defend his mother’s good name — the Amberson name — not to mention the memory of his father (whom he barely noticed when he was alive). When Eugene comes to the door to take Isabel driving, George intercepts him, refuses to let him in, tells him he is no longer welcome, and slams the door in his face.

Isabel waits in vain all afternoon for Eugene to come for her. Instead, late that evening, her brother George arrives, takes her into the parlor and closes the door. Fanny stops Georgie from barging in on them; She knows Uncle George is telling Isabel what her son has done. Too late, Fanny realizes the damage she has done, and is aghast. She realizes that she’s been a fool; she never had a chance with Morgan, and wouldn’t have had, even if Wilbur had lived. She was only letting off steam, and now look what she’s done.

Uncle George has brought a letter from Eugene pleading with Isabel to stand up to her son for the sake of their happiness. But George remains adamant, and the heartbroken Isabel can’t bring herself to go against his wishes. She breaks it off with Eugene once again. “This time,” he laments, “I’ve not deserved it.”

The next day George encounters Lucy downtown. It is clear she doesn’t yet know about the scene with Eugene. She is friendly and cordial, but she keeps the conversation light and trivial, which frustrates George. He had thought losing Lucy would be “no great sacrifice”, but now that he sees her, and she offers no hint of their former intimacy, he knows otherwise. Reminding him of their quarrel, she says since they can’t “play nicely”, they’d best not play at all. He tells her that he and Isabel are going away soon — indefinitely, perhaps permanently — and he may never see her again. She expresses casual regret but wishes him “ever so jolly a time”. Stung, he stalks off. Only when he is gone does Lucy show her true feelings, nearly swooning inside a nearby shop. When she gets home, she finds Fanny Minafer waiting for her, and at last she hears about what George has done to her father. Immediately after Fanny leaves, Lucy burns George’s pictures and all his letters.

The next day George and his mother leave on a round-the-world tour. Fanny has warned George that Isabel’s health is not good, but he refuses to believe it, says she’s the healthiest person he knows. In their absence, real estate values in Amberson Addition decline sharply, so much that the Major is unable to rent all of the new houses he had built.

One evening, relaxing on the veranda, Fanny and Uncle George fall to talking about money-making opportunities in the face of the dwindling Amberson fortune. Old Frank Bronson, the Major’s lawyer, has told George about a new company planning to manufacture automobile headlights; with the proliferation of motorcars like Eugene Morgan’s, this could prove to be a lucrative investment. Fanny and George agree to consider putting some money into the company, agreeing also not to invest more than they can afford to lose.

They ask Eugene’s opinion, and he advises caution, but by then Fanny and George have “the fever” and see the headlight company as a sure-fire way to get rich quick. They both “plunge” on the company, forgetting their resolve not to invest too much. It’s a decision that will have serious consequences.

Finally, after nearly a year and a half abroad, even young George can see that they must return home now if his mother is ever to withstand the journey. As it is, the trip home is so arduous that by the time they arrive Isabel is too weak to walk a step, and Georgie has to carry her up to her room. A doctor and nurse have been summoned and are waiting. Fanny, Uncle George and the Major are desolate, understanding — as young George does not, quite — that Isabel is on her deathbed.

Eugene Morgan hears, and comes to see Isabel, but George again refuses to let him in; if it weren’t for Morgan, he says, none of this would have happened. When Isabel learns that Eugene has been there, she whispers that she would have liked to see him — just once. The next morning she is dead.

Young George is dazed and devastated; he had been clinging to the forlorn hope that she might get better. Even a month later, he is still answering the unspoken reproaches he imagines coming from Uncle George and Aunt Fanny. “What else could I have done?” Before long, his question becomes, “If I was wrong, couldn’t someone have stopped me?” Fanny tells him, bleakly, that no, nobody could stop him; he was too strong, and Isabel loved him too much.

On some level, George seems to understand that his mother died of a broken heart, and that it was he and not Eugene Morgan who broke it. And even in his wretched grief and denial, he certainly knows this: He refused his mother’s dying wish to see Eugene one last time.

With Isabel’s death, the fall of the House of Amberson gathers a terrible momentum. Major Amberson withdraws into his own private contemplation of mortality, where his son and grandson can no longer reach him. The headlight company where Uncle George and Fanny put so much money fails, never having resolved the technical flaws in the product. No one can find a clear title to Isabel’s house, the wedding present from the Major so many years ago; it seems the Major neglected to transfer the deed to Isabel or to register it with the county land office. Nor is the Major any help; his mind seems elsewhere. The two Georges hesitate to question him on the matter, but they hesitate too long; one morning a servant finds the Major dead in the easy chair by his bedroom window.

Between the money Uncle George invested in the headlight company and the share that Sydney and Amelia took (which turns out to have been the only share that was really worth anything), the Major has died virtually penniless. Sydney and Amelia, now living like royalty in their Italian villa, decline to help.

Young George loses his mother’s house and land, and is able to clear only about $600 from the sale of Isabel’s furniture and clothes. Uncle George, thanks to his political connections, lands a minor consulship in South America, but even then he must borrow $200 from his nephew to make the trip to his new home. At their last meeting, before boarding his train, uncle tells nephew that he’s always been fond of him — hasn’t always liked him, but always been fond. You’ve had some hard blows lately, he says, and you’ve taken them like a man. There may be others in this town who are fond of you too; don’t be too proud to turn to them. And with that he is gone; both men understand that they will never see each other again.

George tells Frank Bronson that he can’t take the job, and he hasn’t time to wait to become a lawyer. He needs something that pays well right away. Bronson protests, but George explains that, well, he has much to atone for in his life, and he can’t really make it up to the people he owes it to. The next best thing is to behave decently to poor Fanny, whom he has never really treated very well. Now George has heard that there are well-paying jobs for men in dangerous professions — handling chemicals or explosives, things like that. Bronson reluctantly agrees to help George find such a job: “You certainly are the most practical young man I ever met!”

All this time, Lucy still has feelings for George, and she indirectly admits as much to her father. He doesn’t tell her that he has learned that George has found a job handling nitroglycerin at a chemical plant — a job with a high mortality rate. An old friend tells Eugene that George seems to be trying to do the decent thing for “old Fanny”, and he hints that he (Eugene) might find a safer job for George. Eugene is in fact a silent partner in that chemical plant, and could arrange something without George ever knowing. But Eugene, still bitter, is unwilling to do George any favors.

On one of his Sunday walks, while Fanny is at church, George takes a melancholy stroll through Amberson Addition. The once-stately houses are now rundown, soot-stained and seedy, converted into apartment buildings, boarding houses, shops, lodge halls and the like — or, like the Amberson Mansion and Isabel and Wilbur’s old house, demolished, waiting for the rubble to be carted away. Even the newer houses the Major built as rental properties have been pulled down. The fountains at the intersections are dry and crumbling, the statues lining the streets corroded and pitted. All that’s left of the family name, he muses, is the name of Amberson Boulevard itself. But a corner street sign disabuses him: Amberson Boulevard has been changed to Tenth Street.

Returning to the boarding house, George remembers a book he saw in the parlor, a municipal tome chronicling the 500 most prominent families in the history of the city. He takes the book down, opens to the index, and looks over the names listed there: Abbett, Abbott, Abrams, Adam, Adams, Adler, Akers, Albertsmeyer, Alexander, Allen, Ambrose, Ambuhl, Anderson…

George stares a long time at the page. Five hundred families, and there’s nothing between “Allen” and “Ambrose”. He puts the book back on the shelf. Something has happened that has been a long time coming: Georgie Minafer has had his comeuppance — “three times filled and running over.” But all those people who so longed for it are not there to see it. “Those who were still living had forgotten all about it and all about him.”

In the end, it’s not the nitroglycerin that gets George. Of all things, it’s an automobile. One Sunday, walking downtown, he remembers seeing a young lady stepping into an expensive motorcar. He thought at the time that it might be Lucy, but he couldn’t be sure. Now, standing in the street, he remembers back to that day, and while he’s standing there thinking about the auto in his memory, another auto in the here-and-now runs him down, breaking both his legs. As George lies there in a haze of agony, the driver jumps out of his car and begins jabbering to police that it wasn’t his fault; he’s sorry for George but it wasn’t his fault, and he has a witness. As George lies there dusty and bloodied, waiting for the ambulance, he mutters, “Riffraff!”

Eugene Morgan reads about George’s accident in the paper while on his way to New York on business. His bitterness toward George is unchanged by the young man’s misfortune, but somehow in his reverie he senses the presence of Isabel, and can see her wistful eyes, more than at any time since her death. In New York, on an impulse, he goes to see a spiritual medium, a woman he had visited once before and dismissed as a fake. Now, however, the woman gives him an ambiguous reading that faintly suggests a message from Isabel: A beautiful lady, she says, wants him to “be kind”.

Has Eugene subconsciously fed cues to the woman that enabled her to lead him on this way, or was she really in touch with Isabel? Eugene can’t be sure, but when he returns home he goes straight from the station to the hospital where George is convalescing. He isn’t surprised to find Lucy already there.

Nor is George surprised to see Eugene. “You must have known my mother wanted you to come, so that I could ask you to — to forgive me.”

Eugene takes George’s hand, and Tarkington’s novel ends thus:

But for Eugene another radiance filled the room. He knew that he had been true at last to his true love, and that through him she had brought her boy under shelter again. Her eyes would look wistful no more.

* * *

To be continued…

Minority Opinion: The Magnificent Ambersons, Part 2

Somewhere around the time the story of The Magnificent Ambersons closes — Booth Tarkington was a little hazy on dates — George Orson Welles was born, on May 6, 1915, in Kenosha, Wisconsin. This is how little Orson looked when The Magnificent Ambersons was published in 1918.

Somewhere around the time the story of The Magnificent Ambersons closes — Booth Tarkington was a little hazy on dates — George Orson Welles was born, on May 6, 1915, in Kenosha, Wisconsin. This is how little Orson looked when The Magnificent Ambersons was published in 1918.In other remarks and interviews, Welles went even further: His father, Richard Head Welles, was Booth Tarkington’s best friend. Welles Sr. actually invented an early automobile, but didn’t carry it any further because he couldn’t see any future in it. I wasn’t able to find references to any of these assertions until years, even decades after Welles’s movie of Ambersons.

Then there’s the fact that Orson Welles had a penchant for, well, making things up, especially when he was talking about his father; a 1963 monograph by Maurice Bessy includes a highly amusing load of malarkey about Orson’s father, obviously gleaned from Orson himself. (“Seventy-five percent of what I say in interviews,” he once warned, “is false.”) In fact, other than Orson’s say-so, there’s no evidence that Tarkington and Richard Welles ever met. It’s not entirely out of the question; Richard does appear to have been acquainted with George Ade (another Hoosier writer and contemporary of Tarkington’s, less famous in their day and even more forgotten than Tarkington now). But “best friends” with Tarkington? Unlikely; certainly Orson never said anything about it before 1946, when Tarkington would have been around to weigh in on the subject.

As for inventing the motorcar, the closest Richard Welles ever got to that was acquiring a patent for an automobile jack in 1904. It may be somehow significant that in Orson’s telling, his father becomes something of an amalgam of Eugene Morgan and George Minafer — inventing a car on one hand, deciding it would never amount to anything on the other.

Not that this was anything new; at this stage of his career, divided attention was Orson Welles’s modus operandi. In New York he was famous for keeping busy enough for three men, shuttling back and forth between the stage and radio, even keeping an ambulance on call to ferry him from one live broadcast to another, siren blaring. Now in Hollywood he was doing the same thing, stretching himself as far as Mexico for the Bonito jaunts; even on a slow day he’d be hopping from Ambersons to Journey into Fear and back, sometimes dictating his direction onto phonograph records when he wouldn’t be on the Ambersons set in person. No wonder he thought he could do anything, he’d been doing it so long.

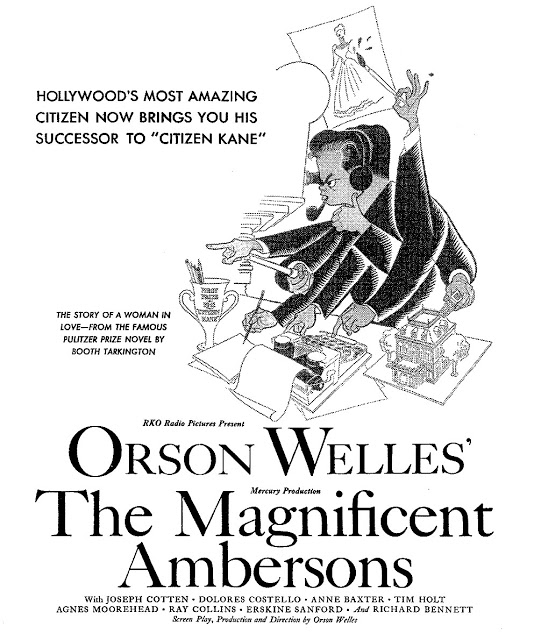

When Welles presented Ambersons on Campbell Playhouse he was already under contract to RKO, though he wouldn’t start work on Citizen Kane for several months. Maybe he really did have an early affection for Tarkington’s book — why else would he have done it on radio in the first place? — but when it came time to choose his second picture as writer-director, he may well have picked it largely because the radio drama had already given him a head start on it. With everything else he had going on, who could blame him? He played a recording of the show for RKO president George Schaefer, who green-lighted the production on the strength of that. (Welles told biographer Barbara Leaming that five minutes into the recording, Schaefer dozed off, waking up only at the end, then giving the go-ahead. Like the story of Tarkington and his father, this one seems not to have surfaced while Schaefer was around to dispute it; he died in 1981 at 92, and Leaming’s 1985 biography was the earliest mention I could find of Schaefer’s nap.)

When Welles presented Ambersons on Campbell Playhouse he was already under contract to RKO, though he wouldn’t start work on Citizen Kane for several months. Maybe he really did have an early affection for Tarkington’s book — why else would he have done it on radio in the first place? — but when it came time to choose his second picture as writer-director, he may well have picked it largely because the radio drama had already given him a head start on it. With everything else he had going on, who could blame him? He played a recording of the show for RKO president George Schaefer, who green-lighted the production on the strength of that. (Welles told biographer Barbara Leaming that five minutes into the recording, Schaefer dozed off, waking up only at the end, then giving the go-ahead. Like the story of Tarkington and his father, this one seems not to have surfaced while Schaefer was around to dispute it; he died in 1981 at 92, and Leaming’s 1985 biography was the earliest mention I could find of Schaefer’s nap.)

Anyhow, awake or asleep, Schaefer approved Ambersons to proceed, alongside Journey into Fear and the still-percolating (and partially shooting in Mexico) Pan-America — but with a renegotiated contract for the Mercury Productions unit. The battle with Hearst over Citizen Kane was still raging, and the RKO board pressured Schaefer to rein Welles in; gone was the free hand and final cut Welles had enjoyed on Kane, and the budget for Ambersons was capped at $600,000. Welles signed, with a confidence he would come to rue.

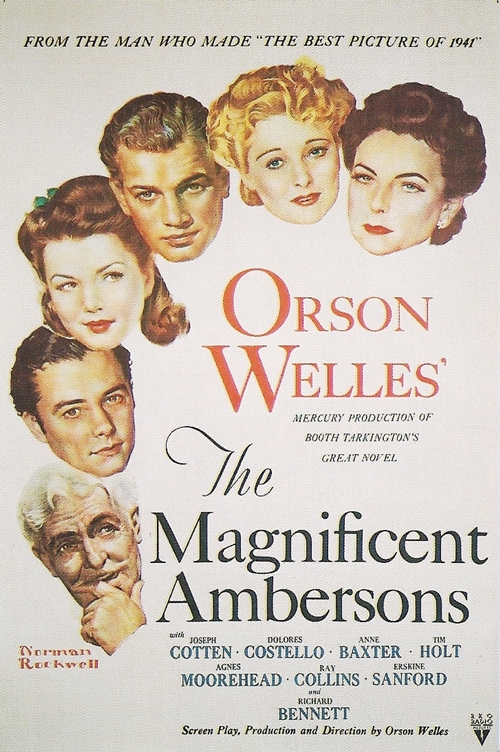

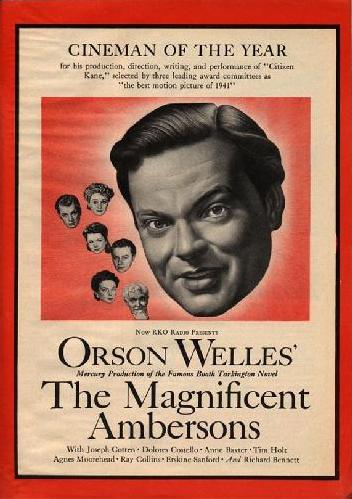

On Ambersons, Ray Collins was set to repeat his Uncle George/Fred role from the radio show (renamed again, to Jack). Stage and silent screen veteran Richard Bennett (father of Constance and Joan) was Major Amberson, Dolores Costello (silent star, ex-wife of John Barrymore and grandmother of Drew) was Isabel Amberson Minafer, Joseph Cotten was Eugene Morgan, and 18-year-old Anne Baxter was Morgan’s daughter Lucy. For the crucial role of Aunt Fanny, Welles tapped Agnes Moorehead, who had played his mother in Citizen Kane; in Ambersons, only her second picture, Moorehead would give the performance of her long and distinguished career — but more of that later.

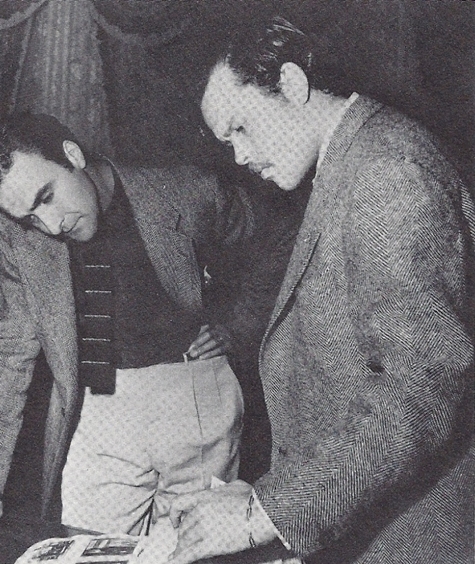

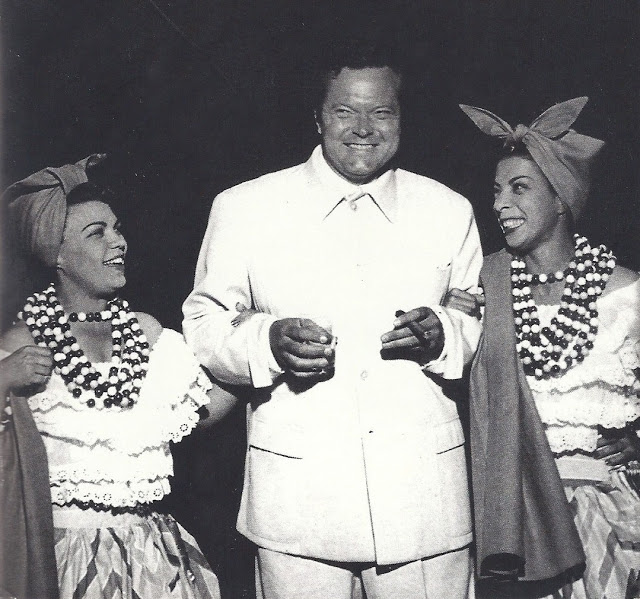

Principal photography began in late October 1941 with the dinner table scene where Georgie denounces the automobile and deliberately offends Eugene Morgan. All things considered, the shoot went well. But there were things to be considered. For one thing, Welles lost cinematographer Gregg Toland, his most valuable and stimulating collaborator on Kane, when Toland enlisted in the U.S. Navy’s photography unit. A last-minute replacement was Stanley Cortez (shown here with Welles). Cortez proved to be an inspired choice, but his slow, methodical style contrasted sharply with the swift, no-nonsense Toland and caused Welles no end of frustration.

Principal photography began in late October 1941 with the dinner table scene where Georgie denounces the automobile and deliberately offends Eugene Morgan. All things considered, the shoot went well. But there were things to be considered. For one thing, Welles lost cinematographer Gregg Toland, his most valuable and stimulating collaborator on Kane, when Toland enlisted in the U.S. Navy’s photography unit. A last-minute replacement was Stanley Cortez (shown here with Welles). Cortez proved to be an inspired choice, but his slow, methodical style contrasted sharply with the swift, no-nonsense Toland and caused Welles no end of frustration.Then there was Welles’s idea of having his cast pre-record their dialogue, lip-synching to playback on the set like singers in a musical. The idea, he said, was to keep actors in touch with the dialogue as they first read it, without camera-induced self-consciousness — plus it would (theoretically) free the camera from worries about boom mikes in the frame, wobbling sound levels and the like. All well and good in theory — but it proved a disaster in practice; if anything, the actors were even more self-conscious, trying to match lips with readings laid down long before. The idea was eventually abandoned, but like most of Welles’s ideas it died hard (he tried it again later for Macbeth over at shoestring Republic, with far more success).

To be continued…

Minority Opinion: The Magnificent Ambersons, Part 3

When the U.S. declared war on Japan on December 8, 1941, the Roosevelt administration felt sure (thanks to confidential intelligence) that Nazi Germany would soon, in turn, declare war on the U.S. And sure enough Hitler did, on December 11. Even before that, however — on December 10 — the U.S. State Department approached Orson Welles. Hitler’s diplomats had been cozying up to South America for years, knowing full well that Germany would come to blows with the U.S. sooner or later, and Washington was alarmed at the number of south-of-the-border governments that had been cozying back. Shoring up relations with Latin America was a top priority. A request came from John Hay Whitney, head of the motion picture section of the State Dept.’s Office of Inter-American Affairs: Would Welles be willing to go down to South America, make a picture, and serve as a goodwill ambassador in the interests of hemispheric solidarity?

When the U.S. declared war on Japan on December 8, 1941, the Roosevelt administration felt sure (thanks to confidential intelligence) that Nazi Germany would soon, in turn, declare war on the U.S. And sure enough Hitler did, on December 11. Even before that, however — on December 10 — the U.S. State Department approached Orson Welles. Hitler’s diplomats had been cozying up to South America for years, knowing full well that Germany would come to blows with the U.S. sooner or later, and Washington was alarmed at the number of south-of-the-border governments that had been cozying back. Shoring up relations with Latin America was a top priority. A request came from John Hay Whitney, head of the motion picture section of the State Dept.’s Office of Inter-American Affairs: Would Welles be willing to go down to South America, make a picture, and serve as a goodwill ambassador in the interests of hemispheric solidarity?Would he ever. The request, forwarded through RKO and with George Schaefer’s blessing, appealed to Welles’s patriotism and political philosophy; better yet, it fit right in with one of his back-burner projects, Pan-America, since retitled It’s All True. (The new title was in fact a bit of a misnomer; the components of the project, insofar as Welles and his staff had thought them through at all, consisted of fictitious episodes, though each dealt with some sort of “truth” about life in the western hemisphere.)

Principal photography on Ambersons wrapped up on January 22, 1942; it had lasted a little over 13 weeks. Welles spent the rest of the month making pickup shots, working with Norman Foster on Journey into Fear and finishing his on-screen role in that picture, making his last broadcast of the Lady Esther radio show, and preparing to leave for South America. On February 2 he left for Rio by way of Washington D.C., where he was to be briefed by officials of the Office of Inter-American Affairs before continuing on to Brazil.

During those same two weeks, Robert Wise assembled a rough cut of Ambersons and traveled with it to Florida to intercept Welles on his way south. They spent February 5 at the Fleischer Animation Studios in Miami, recording Welles’s voice-over narration, screening the rough cut and conferring on Welles’s plans for the final cut — at least, as they stood at that point in time.

During those same two weeks, Robert Wise assembled a rough cut of Ambersons and traveled with it to Florida to intercept Welles on his way south. They spent February 5 at the Fleischer Animation Studios in Miami, recording Welles’s voice-over narration, screening the rough cut and conferring on Welles’s plans for the final cut — at least, as they stood at that point in time.It’s important to remember that what Welles and Wise worked on in Miami was just a rough cut — the barest assemblage of scenes with no music, special effects or fade/dissolve transitions. A rough cut is the movie equivalent of what in live theater is called a stumble-through, plowing through the show from beginning to end just to see what still needs work. The work that the rough cut needed is what the two men talked about that day in Miami; Wise would return to RKO and cut the picture to Welles’s specifications.

At the airport before flying out, Welles dictated a telegram to Jack Moss, the Mercury Theatre’s business manager, whom Welles had appointed a sort of surrogate producer; the telegram specified that Wise was to have the final word on editing Ambersons and that Wise’s authority was not to be questioned. In a wire from Rio three weeks later, Moss was further directed to “start running Ambersons nightly” and taking input from Norman Foster, Joseph Cotten and Dolores Costello “as many times as possible … [Y]ou know I trust you completely.”

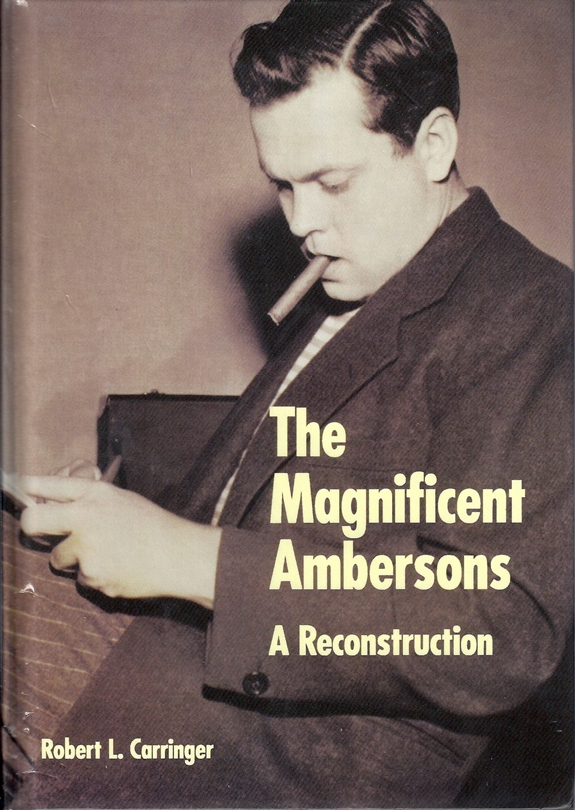

For a clear account of what happened over the four months after Welles flew to Brazil, I am indebted — we all are — to Robert L. Carringer’s The Magnificent Ambersons: A Reconstruction, published by the University of California Press in 1993. The book includes a prefatory essay, “Oedipus in Indianapolis”; an annotated copy of the cutting continuity of the first draft of the picture assembled by Robert Wise after his meeting with Welles in Miami; and a documentary history of the editing process compiled from extant studio records now housed at UCLA and Indiana University. My own conclusions regarding The Magnificent Ambersons differ somewhat from Prof. Carringer’s, but the fact that I even have conclusions is thanks to his painstaking research sifting through the surviving records of RKO and Orson Welles’s personal papers.

For a clear account of what happened over the four months after Welles flew to Brazil, I am indebted — we all are — to Robert L. Carringer’s The Magnificent Ambersons: A Reconstruction, published by the University of California Press in 1993. The book includes a prefatory essay, “Oedipus in Indianapolis”; an annotated copy of the cutting continuity of the first draft of the picture assembled by Robert Wise after his meeting with Welles in Miami; and a documentary history of the editing process compiled from extant studio records now housed at UCLA and Indiana University. My own conclusions regarding The Magnificent Ambersons differ somewhat from Prof. Carringer’s, but the fact that I even have conclusions is thanks to his painstaking research sifting through the surviving records of RKO and Orson Welles’s personal papers.“Who knows what happened?” Welles rhetorically asked Barbara Leaming in the 1980s, referring to the editing of Ambersons while he was in Rio de Janeiro. In fact, the paper trail is thorough and, while cluttered, surprisingly clear — surely one of the most complete editing records for a single picture to survive from the entire Golden Age of Hollywood. And it often flies in the face of the accepted Ambersons legend.

The spine of Prof. Carringer’s reconstruction of Ambersons is the cutting continuity compiled by RKO from the print Robert Wise shipped to Orson Welles in Rio on March 11. The running time at that point was precisely 2 hours 11 minutes 45-and-one-third seconds. (This clarifies another part of the legend, which over the years has alleged various running times, some as high as three hours, for Welles’s version of the picture.) But while this was the most complete version of Ambersons, it was never intended to be the final one; it was understood by all concerned, including Welles, that the picture was running long at 132 minutes and needed further tuning, which could include cutting or retaking scenes (or shooting new ones), and would certainly incude sneak-previewing the picture, standard practice at the time.

The picture at 132 min. contained at least some scenes that evidently never pleased anyone and were among the first things to go. For example, there were what came to be called the first and second porch scenes. The first porch scene, a long take lasting nearly six minutes, involved Isabel and Fanny chatting about their changing town while George sits lost in his own thoughts. After Isabel goes inside, Fanny worries to George that Isabel is being too hasty to leave off mourning her dead husband Wilbur. Fanny then goes inside and George, alone, fantasizes first about Lucy begging his forgiveness, then about her socializing with other young men without a thought for him. This scene might have been deemed too static; also, George’s fantasies may have played badly, may have in fact strained the resources of Tim Holt and Anne Baxter. (A significant number of the edits in the final release version of Ambersons seem to have been aimed at protecting Tim Holt’s performance.)

The second porch scene, another long take lasting a little over three minutes, came later in the picture and showed Fanny and Major Amberson discussing the Major’s financial problems and their mutual plans to invest in the ill-fated headlight company. This was in fact Richard Bennett’s longest scene in the picture, and the 71-year-old Bennett was unable to remember dialogue; Welles had been forced to feed him his lines one-by-one from off-camera, Welles’s voice to be edited out later. If that was the case here, it could well have played havoc with the timing of the scene and made it ultimately unusable. Whatever the reasons, neither porch scene (by unanimous agreement) was ever shown to an audience.

While Wise was still preparing the first cut for shipment, Welles ordered some radical changes, which came to be known as the “big cut”. The following scenes were to be taken out, beginning after George’s slamming the door in Eugene’s face and Eugene’s letter to Isabel pleading with her to stand up to George:

1. George and Isabel discussing Eugene’s letter (a different, shorter version of this scene was eventually reshot for the release version);

2. Isabel slipping a letter under George’s door telling him she will break with Eugene (this scene is not in the release version);

3. George’s walk with Lucy on the street where he tells her he and Isabel are going away, and she frustrates him by her light and trivial attitude;

4. Lucy entering a nearby shop and fainting in front of the startled clerk;

5. A poolroom scene where the clerk tells his buddies about the pretty young lady who fainted in his shop that day (not in release version);

6. The second porch scene between Fanny and Major Amberson (not in release version);

7. Uncle Jack’s visit to Eugene and Lucy, telling them of Isabel’s failing health and George’s refusal to let her come home; and

8. Isabel’s return, when she is too weak to walk a step.

In place of all this, Welles (probably by telephone) ordered Wise to insert a new scene of George finding Isabel unconscious in her bedroom, with Eugene’s letter in her hand. (This scene, not in the release version, was shot under Wise’s direction on March 10.)

Wise went ahead and shipped the first 132-minute cut off to Welles in Rio as planned. Then he made the changes Welles had called for as he prepared Ambersons for its first preview. With the changes Welles had ordered, the picture now ran approximately 110 minutes.

The Magnificent Ambersons had its first sneak preview on Tuesday, March 17, 1942 at the Fox Theatre in Pomona, Calif.

Then all hell broke loose.

To be continued…

Minority Opinion: The Magnificent Ambersons, Part 4

“Who knows what happened?” Orson Welles asked Barbara Leaming in 1984. “I was all covered in confetti trying to pretend I like carnivals, you know. I hate carnivals…” Welles may have been indulging in a little rueful hindsight 40 years after the fact. Simon Callow’s magisterial biography of Welles (two volumes so far, a third and fourth to come), draws on contemporary letters, telegrams, memos and news stories to present a very different picture of Orson Welles in Rio from the one he drew for Leaming.

“Who knows what happened?” Orson Welles asked Barbara Leaming in 1984. “I was all covered in confetti trying to pretend I like carnivals, you know. I hate carnivals…” Welles may have been indulging in a little rueful hindsight 40 years after the fact. Simon Callow’s magisterial biography of Welles (two volumes so far, a third and fourth to come), draws on contemporary letters, telegrams, memos and news stories to present a very different picture of Orson Welles in Rio from the one he drew for Leaming.For one thing, this wasn’t any old “carnival”, some smattering of rides set up in a pasture somewhere with booths for the locals to shoot pellets at plywood ducks and toss dimes into glass candy dishes. This was Carnival, a four-day samba-flavored bacchanal leading up to Ash Wednesday that made Mardi Gras in New Orleans look like a Methodist ice cream social, with a history stretching back to 1723. It’s clear from the record that Welles waded into Carnival with both feet — literally, grabbing one of his crew’s 16mm cameras and venturing out among the millions of revelers to get close shots, emerging drenched with sweat like a man coming out of the sea, all while his Technicolor cameras stood back to get the big picture, lit by the carbon-arc glare of anti-aircraft searchlights. Moreover, his notes and directives to his on-scene staff show that he saw the social and historical roots of Carnival as the core of the Brazilian section of It’s All True — a picture that was growing in scope and ambition by the day, even as Welles remained sketchy about the nuts and bolts of precisely how to get it made.

I don’t want to get sidetracked onto It’s All True, that landmark fiasco from which Welles’s career never recovered. That’s a whole other can of worms. What concerns me here is its effect on Ambersons. When Welles told Barbara Leaming about hating carnivals, he was burnishing the legend of Ambersons being snatched from his loving hands while his back was turned. In fact, at the time, he was reveling in his Brazilian adventure; the movie he was planning appealed to his experimental impulse to let a project find its own shape without conforming to a script, and he reveled as well in immersing himself in this exotic foreign culture. To say nothing of the patriotic duty he was discharging in the cause of inter-American relations.

Welles was fully engaged in shooting Carnival, in recreating sections of it afterward to shoot details his crew had been unable to capture during the crush and riot of the real thing, in mapping out (however vaguely) the other episodes of It’s All True, and in being feted and celebrated as the U.S.’s goodwill cultural ambassador. Fully engaged, but not, it must be said, to the exclusion of all other things; he was still in frequent contact with Robert Wise about Ambersons and with Jack Moss about both Ambersons and Journey into Fear. His ambitious ideas for It’s All True even spilled over into the two pictures he’d left behind: He wanted to shoot some new scenes for himself in Journey, which would mean sending his costume and makeup as Col. Haki to Rio. He wanted to hold the world premiere of Ambersons in Buenos Aires (“resultant international publicity will be enormous”, he wired Schaefer), and to record the picture’s narration in both Spanish and Portuguese. For his part, Schaefer didn’t relish the thought of Welles venturing another 1,200 miles farther from home; a Rio premiere maybe — maybe — but Buenos Aires was out of the question. On February 27, he politely reminded Welles that they still needed to get Ambersons ready for its Easter Week opening in New York (Easter Sunday that year would be April 5); time and tide, Orson, time and tide.

In response, Welles put the Ambersons crew in Hollywood on triple shifts editing and shooting new footage; Wise’s assistant Mark Robson later remembered the two of them moving into a motel near the studio and working as much as 120 hours a week. Even before Welles received Wise’s 132-minute cut, he had ordered the “big cut” and other changes, which Wise made in time for the first preview in Pomona.

1. George tells Eugene that he’s not welcome at Amberson Mansion, slamming the door on him; then —

2. Eugene writes to Isabel, begging her to be strong; then —

3. Isabel reads Eugene’s letter and drops dead (or at least dying) on the spot.

To paraphrase Oscar Wilde, it would take a heart of stone not to weep with laughter at a turn of events like that.

There were other things the Pomona audience didn’t care for. Most of all, they didn’t like Tim Holt. Or more to the point, they didn’t like George Amberson Minafer; Wise reported to Welles that Holt got “a reaction that said: ‘Oh, God, here he is again.'” Indeed, it’s hard to deny that the protagonist of The Magnificent Ambersons is an arrogant, destructive little bastard. In the novel, Tarkington had built sympathy for George despite the awful things he does, giving readers his inner thoughts (however misguided), and sugar-coating this pill much the way Margaret Mitchell finessed the fact that Scarlett O’Hara is a cruel, selfish, conniving bitch. Tyrone Power might have created more sympathy in an audience, as Vivien Leigh did for Scarlett (Prof. Carringer says the same about Welles himself), but Holt had a tougher time hoeing that row. The second half of the so-called “kitchen scene”, where George and Uncle Jack tease Fanny until she runs from the room in tears, originally continued with George spotting the Major’s new houses under construction through the window and running out into the rain to shout his outrage over the roar of the storm — and, in Pomona, over the screams of laughter from the audience.

George Schaefer was in the house that night, and he was rattled to his very bones. RKO had $1 million in Ambersons, and his position at the studio was on the line. Schaefer was Orson Welles’s best friend at RKO, but Schaefer himself had enemies who had been biding their time, ready to pounce. His support for Welles was a large part of it, but not all. Besides the uproar over Citizen Kane and its under-performance at the box office, there had been other expensive losses on Schaefer’s watch. Two of his closest lieutenants had already been sent packing; the tigers were at the gate.

The next day a panicky Schaefer queried RKO’s lawyers about the possibility of — if need be — taking Ambersons out of Welles’s hands. Their answer: Welles’s new contract relinquished his unprecedented right of final cut. He now had the right to cut the picture up to and including the first sneak preview; after that he was subject to the studio’s behest. Reassured, Schaefer waited to see what would happen.

Somewhere around this time Joseph Cotten chimed in, with a letter that Welles never answered and apparently never forgave — in 1984, talking to Barbara Leaming, he was still comparing Cotten to Judas Iscariot. After attending the Pomona preview, Cotten wrote that Welles’s script for Ambersons was “doubtless the most faithful adaptation that any book has ever had” but that “the picture on the screen seems to mean something else…It’s more Chekhov than Tarkington.” (“Yes, exactly!” Welles told Leaming. “That’s just what I was making!”)

Somewhere around this time Joseph Cotten chimed in, with a letter that Welles never answered and apparently never forgave — in 1984, talking to Barbara Leaming, he was still comparing Cotten to Judas Iscariot. After attending the Pomona preview, Cotten wrote that Welles’s script for Ambersons was “doubtless the most faithful adaptation that any book has ever had” but that “the picture on the screen seems to mean something else…It’s more Chekhov than Tarkington.” (“Yes, exactly!” Welles told Leaming. “That’s just what I was making!”)

The focus of Cotten’s concern was the picture’s final scene, when Eugene visits Fanny at her boarding house and tells her of his reconciliation with George in the hospital room after George’s accident. That scene has been the focus of a lot of concern: Cotten was concerned at the time because it was in the picture; others since then, Welles among them, have been concerned because it was cut out and replaced. Even reading the scene in the cutting continuity, and looking at the surviving production photos like this one, it’s easy to see Cotten’s point. The scene is indeed Chekhovian — in fact, it’s reminiscent of the last scene of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya. In the play, Vanya’s niece Sonya speaks wistfully of the days to come, when their troubles will be behind them and “We shall rest”, while Vanya sits desolate and unhappy and a servant plays softly on the guitar. In the boarding house scene, Eugene tells of his making peace with George and being “true at last to my true love” while Fanny sits listless and impassive in her rocking chair and a corny comedy record plays on a Victrola in the background.

Simon Callow suggests that the boarding house scene was an improvement on Tarkington, something that’s beyond confirming or refuting now. What is certain is that it was a departure from Tarkington. Tarkington’s novel ends on a note of reconciliation and hope, even uplift; the boarding house scene ended Welles’s movie on a note of bleak melancholy, suggesting that the reconciliation was too little too late. Cotten, by calling the finished picture “something else” from what he experienced reading the novel, may not have grasped that something else was exactly what Welles was going for. On the other hand, Welles may not have fully grasped the unpleasant taste the scene left in its audience, and the pall it cast over the whole picture, because he never saw it with an audience — or indeed with anyone other than Robert Wise, once, in Miami, a month and a half ago, before the riotous distractions of Carnival and It’s All True.

On March 23, Jack Moss wired Welles with a detailed report describing both preview versions of Ambersons (which makes it possible now to calculate the running times and differences of both versions). Moss also laid out for Welles a compromise plan thrashed out by Robert Wise, Joseph Cotten and himself, which they felt would “remove slow spots and bring out heart qualities” of The Magnificent Ambersons.

It was, as things turned out, almost exactly the form in which the picture was finally released. Orson Welles was having none of it. “My advice absolutely useless,” he wired back on March 25, “without Bob [Wise] here…cannot see remotest sense in any single suggested cut of yours, Bob’s, Jo’s…cannot even begin discussing on proposals as received without doing actual work on actual film with Bob here.”

Moss assured Welles, rather disingenuously, that “every effort being made secure immediate passage for Bob”. But Welles probably knew better. In any case, he now prepared his own detailed plan. It would be his last attempt to retain control of the editing process going on a quarter of the world away.

To be continued…

Minority Opinion: The Magnificent Ambersons, Part 5

In March 1942, Charles W. Koerner replaced Joseph I. Breen as head of production at RKO. The previous July, George Schaefer had lured Breen away from the Hays Office to RKO, and ever since then Breen had served more or less as a rubber stamp for Schaefer’s decisions.

In March 1942, Charles W. Koerner replaced Joseph I. Breen as head of production at RKO. The previous July, George Schaefer had lured Breen away from the Hays Office to RKO, and ever since then Breen had served more or less as a rubber stamp for Schaefer’s decisions.Charles Koerner, however, was made of more contentious stuff. His background was in theater operation; before replacing Breen he had been head of RKO’s exhibition arm in New York. In that position he had surely seen the theater owners’ reports in Motion Picture Herald’s “What This Picture Did for Me” column, and in the case of Citizen Kane the verdict had been “Nothing.”

Koerner was the point man and chief organizer of those who were alarmed at RKO’s march toward insolvency under Schaefer’s stewardship; millions of dollars were gushing out of studio coffers, pittances trickling in. The studio had managed to climb out of receivership only in January 1940, and now it was in danger of falling back into it. Koerner was angling to get Schaefer out of the way, then to put RKO back on a sound financial footing, and he meant to curb what he and his allies saw as the studio throwing good money after bad.

Just to show how the wind was blowing, one of Koerner’s first acts in his new Hollywood office was to send out a memo to the studio at large: The Magnificent Ambersons, Journey into Fear and It’s All True would all proceed — for now — but everyone should check with him before entering into any new agreements with Orson Welles or Mercury Productions. Clearly, George Schaefer wasn’t the only one whose days at RKO were numbered.

Koerner brought an exhibitor’s perspective to his new job; it told him that the shorter the feature, the more showings per day and the more money a theater could make. Koerner also believed that the double feature was the wave of the future (giving credit where it’s due, he was right; the double feature would outlast the studio system itself). He decreed that 90 minutes, give or take a few, was to be the target length for all RKO features, and this edict was conveyed to Robert Wise as he and Mark Robson toiled away on The Magnificent Ambersons.

Meanwhile, down in Rio, Orson Welles was devising his latest and last plan for re-cutting Ambersons. He transmitted his instructions to Jack Moss and Wise in a 30-page telegram on March 27. He probably didn’t know about Koerner’s 90-minute cap on feature length, but it may not have made any difference if he did.

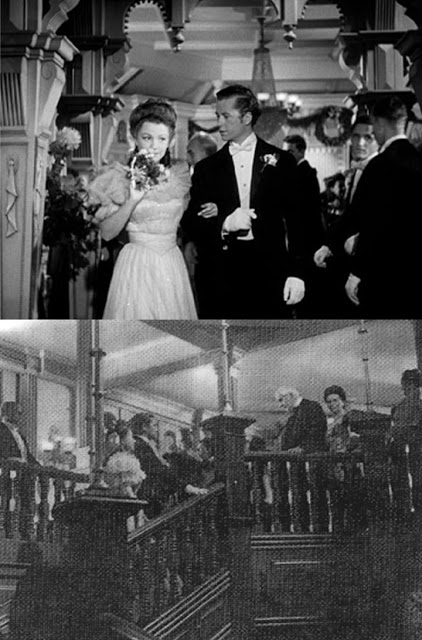

We can’t know what the running time of Welles’s March 27 cut would have been because it was never assembled, much less screened for an audience. Welles ordered some major changes from the last version he had called for, the one previewed in Pomona. In the Christmas ball scene, he wanted a dissolve from the moment when George and Lucy dance away from the camera (after she asks “What do you want to be?” and he replies “A yachtsman.”) directly to the scene of Lucy and Eugene putting their horseless carriage away in the barn as they return home (a scene that is not in the release version). As Robert L. Carringer says, this would entail losing this shot of Eugene and Isabel dancing alone after all the other guests have gone, “what many regard as the single most beautiful shot in the film.”

We can’t know what the running time of Welles’s March 27 cut would have been because it was never assembled, much less screened for an audience. Welles ordered some major changes from the last version he had called for, the one previewed in Pomona. In the Christmas ball scene, he wanted a dissolve from the moment when George and Lucy dance away from the camera (after she asks “What do you want to be?” and he replies “A yachtsman.”) directly to the scene of Lucy and Eugene putting their horseless carriage away in the barn as they return home (a scene that is not in the release version). As Robert L. Carringer says, this would entail losing this shot of Eugene and Isabel dancing alone after all the other guests have gone, “what many regard as the single most beautiful shot in the film.”  Welles also called for cutting this shot, the iris-out on the horseless carriage as it trundles along in the snow with everyone singing “The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo”. This would entail no substantial loss, but the iris-out is a truly lovely moment that evokes the period as vividly as any four seconds in the whole picture. Prof. Carringer calls cutting it “another great surprise”, but I’d go further than that; I’d say it’s a real head-scratcher, a cut that loses far more than the time it saves. I think, just maybe, if I’d been Robert Wise, I might have started to wonder if, in all the bustle and flurry of It’s All True, Orson had perhaps begun to lose touch with the movie he was making before he flew off to Brazil. But never mind, that’s just me thinking out loud; I don’t want to put thoughts into Wise’s 1942 head.

Welles also called for cutting this shot, the iris-out on the horseless carriage as it trundles along in the snow with everyone singing “The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo”. This would entail no substantial loss, but the iris-out is a truly lovely moment that evokes the period as vividly as any four seconds in the whole picture. Prof. Carringer calls cutting it “another great surprise”, but I’d go further than that; I’d say it’s a real head-scratcher, a cut that loses far more than the time it saves. I think, just maybe, if I’d been Robert Wise, I might have started to wonder if, in all the bustle and flurry of It’s All True, Orson had perhaps begun to lose touch with the movie he was making before he flew off to Brazil. But never mind, that’s just me thinking out loud; I don’t want to put thoughts into Wise’s 1942 head. I don’t want to put thoughts into Welles’s head either, but I have to speculate on why he was willing to trim so much meat (a little over four minutes) off the tail end of the ball scene after the “yachtsman” line. I suspect Welles was focused on preserving the sequence that made up the centerpiece of the Amberson ball — the one that had consumed nine ten-hour days and occupied a crew of 100 to shift walls, doors and step units in and out of place as Tim Holt, Anne Baxter, Joseph Cotten, Ray Collins et al. strolled and chatted amid their splendid surroundings, alternately basking in them and taking them for granted.

I don’t want to put thoughts into Welles’s head either, but I have to speculate on why he was willing to trim so much meat (a little over four minutes) off the tail end of the ball scene after the “yachtsman” line. I suspect Welles was focused on preserving the sequence that made up the centerpiece of the Amberson ball — the one that had consumed nine ten-hour days and occupied a crew of 100 to shift walls, doors and step units in and out of place as Tim Holt, Anne Baxter, Joseph Cotten, Ray Collins et al. strolled and chatted amid their splendid surroundings, alternately basking in them and taking them for granted.

Two scenes — (1) the buggy ride scene, where George and Lucy quarrel over George’s reluctance to “make something of himself”, and (2) the following carriage scene between Uncle Jack and Major Amberson, talking about the changes in their town and the decline in the family fortune — Welles wanted to move to much earlier, before Wilbur Minafer’s funeral. This would, as Robert L. Carringer notes, get on more directly with the development of George and Lucy’s relationship — and perhaps compensate somewhat for the loss of the development of their relationship as they sit on the stairs at the end of the ball. At any rate, this was not done — both scenes remained later in the picture — but another of Welles’s edits was implemented: At Wilbur’s death, instead of the shot of Wilbur’s tombstone that was in place, he ordered a new shot of townspeople, with one saying “Wilbur Minafer. Quiet man. Town will hardly know he’s gone.” (“Phone me to get correct reading for line.”) In the release version the line is spoken by Erskine Sanford as Roger Bronson.

At Welles’s direction, a shot of George Minafer’s diploma was cut, which leads to some inevitable confusion in the beginning of the kitchen scene between Fanny and George (and later Jack); at first it seems to follow Wilbur’s funeral rather than coming months later after George’s graduation and return home. This is probably unavoidable since scenes of George’s life at college, and Jack, Isabel and Eugene attending his commencement — all of which are in the novel — were never shot. Welles also directed that the kitchen scene end before George sees the construction outside in the yard, and this was also done in the final version.

Welles called for keeping the first porch scene, ending it before George’s fantasies about Lucy, but the scene remained out.

As for the “big cut” that so truncated the lingering death of Isabel Amberson Minafer, and which Moss and Wise had restored for the Pasadena preview, Welles wanted that footage taken out again, with other changes and re-shoots that he felt would improve what remained. But he had evidently had second thoughts about the Moss-Wise-Cotten compromise plan he had dismissed out of hand on March 25, and now was willing to go along with some of their suggestions, especially the major restructuring after Isabel’s death: Jack and George’s farewell at the railroad station, the “Indian legend” scene with Lucy and Eugene, the scene of Fanny’s breakdown as she and George discuss their financial straits, George in Bronson’s office giving up his hopes for a career in law, and George’s last walk home to Amberson Mansion, where he gets his come-uppance (“Mother, forgive me … God, forgive me.”)

In a letter to Welles dated March 31, Robert Wise summarized the audience reaction at both previews (“I have never tackled a more difficult chore … it’s so damn hard to put on paper in cold type the many times you die through the showing…”) Wise went through the picture step by step; he didn’t always distinguish between one audience and the other, but he made a point to say how well some of the “big cut” scenes had played, which the Pomona crowd hadn’t seen but the Pasadena audience had. Wise again emphasized the problematic nature of the last scene between Fanny and Eugene: “The boarding house got us several laughs, one on the man’s face when the door opens and several through the scene on Fanny’s strange behavior, and here again we could feel great restlessness.”

Welles was determined to retain the boarding house scene, and he thought he had the solution to everyone’s concerns. It would come in the closing credits, which were to be spoken by Welles with shots illustrating each name as it came up. “To leave audience happy for Ambersons,” he wired Jack Moss on April 2, “remake cast credits as follows…” First he wanted an oval framed picture of Richard Bennett “in Civil War campaign hat”, presumably made up to look younger than he does in the movie itself; then, “live shot of Ray Collins … in elegant white ducks and hair whiter than normal seated on tropical veranda ocean and waving palm trees behind him … [then, Agnes Moorehead] blissfully and busily playing bridge with cronies in boarding house.” And so on, down to Joseph Cotten looking out a window at Tim Holt and Anne Baxter as they drive away, waving at Eugene/Joseph behind them: ” … they turn to each other then forward both very happy and gay and attractive for fadeout.”

Welles was determined to retain the boarding house scene, and he thought he had the solution to everyone’s concerns. It would come in the closing credits, which were to be spoken by Welles with shots illustrating each name as it came up. “To leave audience happy for Ambersons,” he wired Jack Moss on April 2, “remake cast credits as follows…” First he wanted an oval framed picture of Richard Bennett “in Civil War campaign hat”, presumably made up to look younger than he does in the movie itself; then, “live shot of Ray Collins … in elegant white ducks and hair whiter than normal seated on tropical veranda ocean and waving palm trees behind him … [then, Agnes Moorehead] blissfully and busily playing bridge with cronies in boarding house.” And so on, down to Joseph Cotten looking out a window at Tim Holt and Anne Baxter as they drive away, waving at Eugene/Joseph behind them: ” … they turn to each other then forward both very happy and gay and attractive for fadeout.”“As solutions go,” says Prof. Carringer, “this one could only have raised doubts about how fully Welles comprehended the gravity of the situation.” Indeed so, if Welles thought he could win an audience over with a cheerful curtain call of George/Tim and Lucy/Anne waving and smiling at the audience as they drive off into the sunset. This would surely register only as a breezy non sequitur. The same goes for Welles’s intention to show Richard Bennett in a Civil War uniform or Ray Collins basking on a tropical beach; these poses would have looked particularly odd since no version of the picture ever referred to Major Amberson’s Civil War service or Uncle Jack’s obtaining a South American consulship. To someone who had just sat through the picture, it would look as if Richard Bennett was dressed for a costume party and Ray Collins off on a vacation from Hollywood; if an audience was inclined to laugh at The Magnificent Ambersons, none of this would have persuaded them to stifle their giggles. In the end this suggestion was not followed; the cast list showed the actors in medium closeup, turning to regard the camera with friendly half-smiles.

There is in fact some reason to believe that Robert Wise had begun to think Welles had lost touch with the picture. “I’ve always felt,” Wise said years later, “that if Orson had been at the preview and had seen and heard that reaction, he’d have understood better what did and didn’t work in it. As it was, Mark Robson and I were in touch with him almost every day, these long, long telegrams — 20, 30 pages sometimes. It would have been so much easier if he could have been there.” Schaefer — deciding, perhaps, that the law of diminishing returns was kicking in — called a temporary halt to any activity on Ambersons, to let Wise, Robson and Moss recharge their batteries, and to try to reach some agreement with Welles.

Adding to the fear that Welles had lost touch with Ambersons was the very real fact that he seemed to have lost control of It’s All True — if, indeed, he’d ever had control of it in the first place. After Carnival, the weather in Rio had turned awful and wouldn’t let up — constant bitter cold and thundering rains that made outdoor shooting impossible. An expected shipment of supplies and equipment seemed endlessly delayed. The crew idled and grumbled, piddling along with what interior pickup shots could be managed, often without Welles even being present, and with little sense of exactly what they were shooting (when they were shooting) or why. “Everything here proceeding beautifully,” Welles blithely wired Schaefer, but production manager Lynn Shores — a querulous, irascible man who was virtually a spy for the anti-Welles faction at RKO — painted a much bleaker picture. Shores carped about everything, from spending all night in “meaningless conferences” with Welles to having to be the one calling “action” and “cut” when Orson wasn’t around. Shores, ever the proud martyr, portrayed himself as the only thing standing between the crew and demoralized, mutinous chaos.

Schaefer probably knew to consider the source, but enough reports were coming in from second, third and fourth parties to suggest that Shores’s sour perspective was closer to the truth than Welles’s. Finally, in mid-April, Schaefer transferred full responsibility for editing Ambersons to Robert Wise and told him just to do whatever was necessary to get the picture in a releasable form.

Actors were called back to shoot retakes and new inserts. There was a new scene (directed by Wise) between George and Isabel after they’ve read Eugene’s letter, omitting or softening some of George’s wilder overreactions (“It’s simply the most offensive piece of writing that I’ve ever held in my hands … if he ever set foot in this house again … I … I can’t speak of it.”). A scene (by assistant director Freddie Fleck) of Eugene being turned away by George, Fanny and Jack as Isabel lies dying upstairs. A shortened opening (directed by Jack Moss) for the scene between George and the hysterical Fanny in the empty Amberson Mansion. Another scene (Fleck again) in which first Lucy, then Eugene, decide to visit George in the hospital after his auto accident.

And, most notoriously, this. Audience reaction and response cards had convinced everyone but Welles that his beloved boarding house scene had to go, so it was replaced with this one between Eugene and Fanny in the corridor outside George’s hospital room. Much of the dialogue was the same, but with a more upbeat reading from Joseph Cotten and a more serenely blissful reaction from Agnes Moorehead; the result was closer to Tarkington’s ending — though a far cry from the melancholy, even sullen tone that Welles had so carefully set, and which Joseph Cotten had found more Chekhov than Tarkington. Simon Callow says this scene was directed by Jack Moss; Prof. Carringer says it was Freddie Fleck. But whoever was responsible, they both hate it, as does nearly everybody who’s ever had an opinion on Ambersons.

And, most notoriously, this. Audience reaction and response cards had convinced everyone but Welles that his beloved boarding house scene had to go, so it was replaced with this one between Eugene and Fanny in the corridor outside George’s hospital room. Much of the dialogue was the same, but with a more upbeat reading from Joseph Cotten and a more serenely blissful reaction from Agnes Moorehead; the result was closer to Tarkington’s ending — though a far cry from the melancholy, even sullen tone that Welles had so carefully set, and which Joseph Cotten had found more Chekhov than Tarkington. Simon Callow says this scene was directed by Jack Moss; Prof. Carringer says it was Freddie Fleck. But whoever was responsible, they both hate it, as does nearly everybody who’s ever had an opinion on Ambersons.The Magnificent Ambersons finally saw release on July 10, missing not only Easter Week, but Memorial Day, Flag Day and the Fourth of July as well. And forget Radio City Music Hall; in New York it played the 4,000-seat Capitol — still a picture palace, but hardly the RKO flagship. And not all of the picture’s play dates were that prestigious; in some places it ran on a double bill with Lupe Velez in Mexican Spitfire Sees a Ghost — with Ambersons as the bottom half. Despite RKO’s malign neglect and a $625,000 loss, the picture impressed enough Academy voters by early 1943 to garner four Oscar nominations: for best picture, best art direction/interior decoration, Stanley Cortez’s cinematography, and Agnes Moorehead’s harrowing performance as the neurotic, sexually frustrated Fanny.

But even before the picture’s release, the game was up. George Schaefer, maneuvered by Charles Koerner into a lame duck, finally resigned on June 26. Koerner had been stewing since May over a report from the budget office that It’s All True had cost $526,000 so far and would take at least another $595,000 to finish; now, finally rid of Schaefer, Koerner pounced. He cut off Welles’s money and ordered the unit back to Hollywood forthwith. When Welles, enthusiastic about the Four Men on a Raft episode he was currently involved in, pleaded to finish it, Koerner granted him $10,000, one camera, and 40,000 feet of film; let him see how long that would last. Finally, the killing blow: Koerner evicted Mercury Productions from the RKO lot, giving them 24 hours to vacate the premises. In a telegram from Brazil, Welles tried to buck up his people’s spirits: “Don’t get excited. We’re just passing a rough Koerner on our way to immortality.” In rebuttal, the Koerner faction had a pun of their own: “All’s well that ends Welles.”

To be concluded…

Minority Opinion: The Magnificent Ambersons, Part 6

I worked with Robert Wise once. In 1986 I played a small role in Wisdom, on which he served as executive producer and all-round good shepherd for first-time writer-director Emilio Estevez. My scene was a small one, only about 45 seconds on screen, but it meant two twelve-hour days on the set. As I reported for work on my first day, Wise came up to me and introduced himself (as if it were necessary!). There was something I had thought and said about him more than once in the past, but now, to my amazement, I actually had the chance to say it to him in person: “I have to tell you, Mr. Wise, I think you’re the greatest film editor who ever picked up a pair of scissors.”