Picture Show 2022 — Day 1

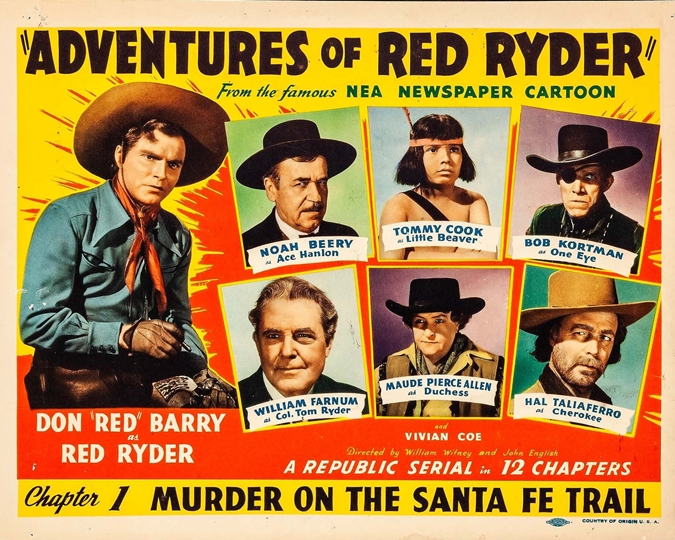

A feature of the last few Cinevents that The Picture Show wisely chose to continue this year is the 12-chapter serial, screening three chapters at the beginning of each of the convention’s four days. As in prior years, this year’s serial was from Republic — naturally enough, since Republic was, well, if not the Tiffany’s, at least the Zale’s of chapter-play production. And after the relatively exotic serials of the last few years — with heroes taking on a Japanese spy ring during World War II (The Masked Marvel, Cinevent 50), lost-world savages on a volcanic island above the Arctic Circle (Hawk of the Wilderness, C-51), and Teutonic saboteurs before America’s entry into the war (King of the Texas Rangers, C-52) — this one, for a refreshing change of pace, was a standard, good old-fashioned cowboy shoot-’em-up, Adventures of Red Ryder (1940). As anybody who ever read a comic book or the funny-pages in a newspaper between 1938 and 1964 can tell you, Red Ryder was the tall, square-jawed, white-hatted, red-haired hero of the Painted Valley Ranch in the Blanco Basin of the San Juan Mountains, noted for never killing the bad guys but simply shooting the guns out of their hands. His gal was Beth Wilder, his youthful Native American sidekick was Little Beaver, and his archenemy was the dastardly Ace Hanlon. Red made his debut in newspapers in 1938, then expanded to comic books in 1939, this Republic serial in 1940, radio in 1942, B-movie features in 1944, and even a couple of unsold pilots for TV series in the 1950s and ’60s.

A feature of the last few Cinevents that The Picture Show wisely chose to continue this year is the 12-chapter serial, screening three chapters at the beginning of each of the convention’s four days. As in prior years, this year’s serial was from Republic — naturally enough, since Republic was, well, if not the Tiffany’s, at least the Zale’s of chapter-play production. And after the relatively exotic serials of the last few years — with heroes taking on a Japanese spy ring during World War II (The Masked Marvel, Cinevent 50), lost-world savages on a volcanic island above the Arctic Circle (Hawk of the Wilderness, C-51), and Teutonic saboteurs before America’s entry into the war (King of the Texas Rangers, C-52) — this one, for a refreshing change of pace, was a standard, good old-fashioned cowboy shoot-’em-up, Adventures of Red Ryder (1940). As anybody who ever read a comic book or the funny-pages in a newspaper between 1938 and 1964 can tell you, Red Ryder was the tall, square-jawed, white-hatted, red-haired hero of the Painted Valley Ranch in the Blanco Basin of the San Juan Mountains, noted for never killing the bad guys but simply shooting the guns out of their hands. His gal was Beth Wilder, his youthful Native American sidekick was Little Beaver, and his archenemy was the dastardly Ace Hanlon. Red made his debut in newspapers in 1938, then expanded to comic books in 1939, this Republic serial in 1940, radio in 1942, B-movie features in 1944, and even a couple of unsold pilots for TV series in the 1950s and ’60s.

In addition to being the avatar of clean living and upright law and order, Red Ryder was also a pioneer of tie-in merchandising. Millions who weren’t even born when the Red Ryder strip ended in 1964 are nevertheless aware, thanks to 1983’s A Christmas Story, of the Daisy Official Red Ryder Carbine-Action 200-Shot Range Model Air Rifle With a Compass in the Stock and This Thing Which Tells Time, first marketed in 1940 and — believe it or not! — still available from the Daisy Manufacturing Company of Rogers, Arkansas (not that exact model, now discontinued, but plenty of others).

But back to that 1940 Republic serial. The story was the old western trope about the crooked banker in cahoots with outlaws to terrorize local ranchers into selling their property dirt cheap so the banker can make a handsome profit by selling to the railroad that only he knows is coming through. Red was the son of one such rancher, swinging into action when his father is murdered after getting too close to discovering the banker’s plot.

The serial was directed by William Witney and John English (the same team responsible for Hawk of the Wilderness and King of the Texas Rangers), and Red was played by Don “Red” Barry. Neither Witney nor English thought Barry was right for the part, and Barry himself later admitted he was miscast — at 5 ft. 4, he was a full foot shorter than the lanky Red Ryder of the comics. But Republic president Herbert Yates insisted (he compared Barry to James Cagney), and that was that. Evidently, Barry suffered from a short-man pugnacity complex, because both directors came to detest him, as did most of the cast and crew — leading lady Vivian Coe, as Red’s girl (renamed Beth Andrews), remembered, “I don’t like saying negative things about the departed, but he wasn’t a very nice fellow,” and Barry himself, years later, admitted he had been “a brash, smart ass young punk.” Still, it must be said that Barry does okay in the part, playing Red Ryder as a bantam rooster rather than the tall-in-the-saddle type — though it does take some suspension of disbelief when Red goes into fistfights with baddies who have several inches and 20-30 pounds on him (Noah Beery Sr., the serial’s Ace Hanlon, was 6 ft. 1 in.)

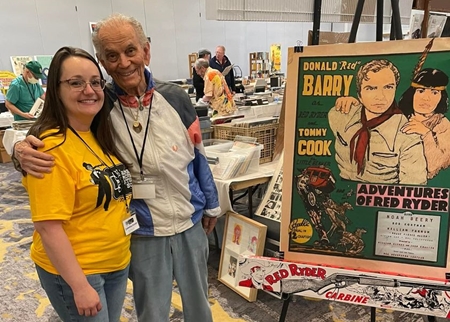

Little Beaver was played by nine-year-old Tommy Cook, who is not only still with us at 91 (the last survivor of this or any other Republic serial), but was an honored guest in Columbus; here he is shown with Picture Show Chair Samantha Glasser in the Dealers Room. (And by the way, do you see what’s hanging on the easel under the poster for the serial? Yep, it’s a Daisy Red Ryder BB gun. They raffled one off during the weekend — albeit with no compass or sundial in the stock — and I admit I was tempted for a second or two. But [1] I’d never have gotten it on the plane; and [2] even if I had it shipped to my home, what could I do with it then? I’d probably just shoot my eye out.)

Little Beaver was played by nine-year-old Tommy Cook, who is not only still with us at 91 (the last survivor of this or any other Republic serial), but was an honored guest in Columbus; here he is shown with Picture Show Chair Samantha Glasser in the Dealers Room. (And by the way, do you see what’s hanging on the easel under the poster for the serial? Yep, it’s a Daisy Red Ryder BB gun. They raffled one off during the weekend — albeit with no compass or sundial in the stock — and I admit I was tempted for a second or two. But [1] I’d never have gotten it on the plane; and [2] even if I had it shipped to my home, what could I do with it then? I’d probably just shoot my eye out.)

My only regret of the weekend is that I didn’t get a chance to meet and chat with Mr. Cook; for one thing, I’d have liked to hear what he had to say about working with Red Barry. Somehow I even managed to miss his interview with Caroline Breder-Watts on Saturday morning. But The Picture Show’s Facebook page has a video excerpt of that interview in which Mr. Cook tells an amusing anecdote about doing a whisky commercial with Orson Welles; he (Mr. Cook) could easily pass for 25 years younger than he is. Click here.

The first feature of the weekend, Behind the News, was also from Republic, and also from 1940. Lloyd Nolan played a once-great reporter for a major newspaper in “State City” (probably a pseudonym for San Diego, Calif., since the plot later reveals it to be within driving distance of Calexico). Now jaded and cynical, he gets an annoying kick in the conscience when his latest padded expense account enrages his harried managing editor (reliable old Robert Armstrong). To get back at the reporter, the editor saddles him with an idealistic gee-whiz cub reporter straight out of journalism school (the prolific Frank Albertson, best remembered now as Sam “Hee-haw!” Wainwright in It’s a Wonderful Life). When the youngster’s gung-ho admiration for his past work shows Nolan up for the bitter, burned-out failure he has become, he arranges a series of humiliations that ruin Albertson’s standing at the paper. Then Albertson uncovers a case of an innocent Mexican-American being railroaded on a trumped-up murder charge, but nobody will believe him, so Nolan’s long-suffering girlfriend (the earnest, likable Doris Davenport) prods him into taking the boy’s part. It was a solid little newspaper melodrama, well-plotted and snappily directed by Joseph Santley.

The first feature of the weekend, Behind the News, was also from Republic, and also from 1940. Lloyd Nolan played a once-great reporter for a major newspaper in “State City” (probably a pseudonym for San Diego, Calif., since the plot later reveals it to be within driving distance of Calexico). Now jaded and cynical, he gets an annoying kick in the conscience when his latest padded expense account enrages his harried managing editor (reliable old Robert Armstrong). To get back at the reporter, the editor saddles him with an idealistic gee-whiz cub reporter straight out of journalism school (the prolific Frank Albertson, best remembered now as Sam “Hee-haw!” Wainwright in It’s a Wonderful Life). When the youngster’s gung-ho admiration for his past work shows Nolan up for the bitter, burned-out failure he has become, he arranges a series of humiliations that ruin Albertson’s standing at the paper. Then Albertson uncovers a case of an innocent Mexican-American being railroaded on a trumped-up murder charge, but nobody will believe him, so Nolan’s long-suffering girlfriend (the earnest, likable Doris Davenport) prods him into taking the boy’s part. It was a solid little newspaper melodrama, well-plotted and snappily directed by Joseph Santley.

Behind the News was also the swan song of Doris Davenport after six years and nine pictures, four of them with no screen credit. At the beginning and end of those six years she did seem to be going places. Her first picture was in 1934, playing Eddie Cantor’s girlfriend in Kid Millions. Other bits followed, interspersed with fashion modeling to make ends meet. In 1938, under the name Doris Jordan, she tested for Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With the Wind and, according to Dave Domagala’s program notes, “was actually one of the finalists.” (Well, actually, “one of the semi-finalists” is more like it. On November 18, 1938, David Selznick listed his Scarlett front-runners as Paulette Goddard, Doris Jordan, Jean Arthur, Katharine Hepburn, and Loretta Young, adding that “Jordan is a complete amateur”. By December 12, Selznick was writing, “it’s narrowed down to Paulette, Jean Arthur, Joan Bennett, and Vivien Leigh” — with Leigh having the inside track.) Doris Jordan/Davenport’s test for Scarlett impressed producer Samuel Goldwyn enough to get her cast in The Westerner (1940) opposite Gary Cooper for director William Wyler. Wyler wasn’t impressed (he wanted her part for his wife, Margaret Tallichet), but Goldwyn thought she had real star potential. After that came Behind the News — then nothing. Some sources say she simply got no further offers, though it seems likely that if nothing else, Republic at least could have found something for her to do. One dramatic story, attributed to David Ragan’s Who’s Who in Hollywood but unconfirmed anywhere else, claims that an auto accident after shooting The Westerner crushed her legs and forced her to use a cane for the rest of her days. Grain of salt on that one, I think; if that’s true, then how did she make Beyond the News? Whatever the reason, Doris Davenport lived on until 1980 but never made another picture.

Behind the News was also the swan song of Doris Davenport after six years and nine pictures, four of them with no screen credit. At the beginning and end of those six years she did seem to be going places. Her first picture was in 1934, playing Eddie Cantor’s girlfriend in Kid Millions. Other bits followed, interspersed with fashion modeling to make ends meet. In 1938, under the name Doris Jordan, she tested for Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With the Wind and, according to Dave Domagala’s program notes, “was actually one of the finalists.” (Well, actually, “one of the semi-finalists” is more like it. On November 18, 1938, David Selznick listed his Scarlett front-runners as Paulette Goddard, Doris Jordan, Jean Arthur, Katharine Hepburn, and Loretta Young, adding that “Jordan is a complete amateur”. By December 12, Selznick was writing, “it’s narrowed down to Paulette, Jean Arthur, Joan Bennett, and Vivien Leigh” — with Leigh having the inside track.) Doris Jordan/Davenport’s test for Scarlett impressed producer Samuel Goldwyn enough to get her cast in The Westerner (1940) opposite Gary Cooper for director William Wyler. Wyler wasn’t impressed (he wanted her part for his wife, Margaret Tallichet), but Goldwyn thought she had real star potential. After that came Behind the News — then nothing. Some sources say she simply got no further offers, though it seems likely that if nothing else, Republic at least could have found something for her to do. One dramatic story, attributed to David Ragan’s Who’s Who in Hollywood but unconfirmed anywhere else, claims that an auto accident after shooting The Westerner crushed her legs and forced her to use a cane for the rest of her days. Grain of salt on that one, I think; if that’s true, then how did she make Beyond the News? Whatever the reason, Doris Davenport lived on until 1980 but never made another picture.

Next came three silent Our Gang shorts from Hal Roach, The Champeen (1923) featuring Ernie “Sunshine Sammy” Jackson, Roach’s first African-American child star, then Barnum & Ringling, Inc. and The Spanking Age (both 1928).

The last feature before the dinner break was a highlight of the whole weekend, at least as far as I was concerned: Love Among the Millionaires (1930) starring Clara Bow. I’ve said it before but it bears repeating, and I’ll repeat it as often as I feel it’s necessary: There was never a more charming and delightful movie star than Clara Bow. As charming and as delightful, granted, but more so? None. Ever.

That said, I must concede that if somebody asked me what was the big deal about Clara Bow, Love Among the Millionaires isn’t necessarily the first movie I’d point them to. (Where would I point them, you ask? Well…to Mantrap [1926], Wings and It [both ’27] — pretty much in that order.)

With Millionaires, the story sets Clara up as a diner waitress being romanced by the son of a railroad tycoon, then playing the low-class hussy to drive him away and spare him being disowned by his father. It was too familiar by half, as old as La Dame aux Camélias and as recent as Mary Pickford in My Best Girl (1927). Worse, it didn’t play to Clara’s strengths, as critics at the time were quick to point out. As Richard Barrios suggests in his insightful history A Song in the Dark, it’s almost as if Paramount were trying to turn Clara into Janet Gaynor — a wasted effort, you’d think, considering that she was already Clara Bow. (Richard, by the way, also wrote Love Among the Millionaires’ notes for The Picture Show program.)

Today, with hindsight, we know that Clara’s career was deep into twilight; her off-screen emotional problems were catching up, and while her supposed mike-fright didn’t show as much as later legend has it, the fun was going out of the work for her, and public scandals were belying the Janet Gaynor act. There was an unspoken sense that her career wasn’t on the right track; fan magazines were speculating on who would be “the next Clara Bow” — the implication being that the present one wouldn’t be on top much longer.

Still, Love Among the Millionaires was a hit — the true measure of Clara’s stardom, as with all stars past, present and future, was that she was expected and able to carry material like this. To be fair, she didn’t bear the burden alone. She got good support from 9-year-old Mitzi Green (shown here) as her brassy sister, Charles Sellon as their father, and Stanley Smith as Clara’s boyish sweetheart. Comic relief was provided by Stuart Erwin and Skeets Gallagher as two would-be suitors for Clara’s hand — although frankly, they come off more as a bickering couple than as romantic rivals.

Still, Love Among the Millionaires was a hit — the true measure of Clara’s stardom, as with all stars past, present and future, was that she was expected and able to carry material like this. To be fair, she didn’t bear the burden alone. She got good support from 9-year-old Mitzi Green (shown here) as her brassy sister, Charles Sellon as their father, and Stanley Smith as Clara’s boyish sweetheart. Comic relief was provided by Stuart Erwin and Skeets Gallagher as two would-be suitors for Clara’s hand — although frankly, they come off more as a bickering couple than as romantic rivals.

I’ve always enjoyed Love Among the Millionaires, and I was happy for the chance to see it again in Columbus. It was Clara’s only real musical — her ability to sell a song had surprised everyone, not least herself, in Paramount on Parade earlier in 1930 — and while her untrained voice was no threat to Jeanette MacDonald, she could carry a tune. The L. Wolfe Gilbert/Abel Baer songs may not be classics, but they’re catchy enough, and she puts them across — singing live on the set, mind you — with confidence and infectious gusto. As Richard Barrios says in his program notes, if musicals hadn’t fallen out of favor and her own demons hadn’t overwhelmed her, Clara might have reinvented herself for the sound era. But by the time musicals came back in style, she was out of the biz for good.

After dinner came the first of the weekend’s Laurel and Hardy shorts, Our Wife (1931). Stan and Ollie try to pull off an elopement, spiriting Oliver’s intended Dulcy (Babe London) out from under the disapproving nose of her daddy James Finlayson. Ollie entrusts Stan with the task of finding a getaway car, and the disasters pile up from there. When the wedding party finally arrives before the justice of the peace, he turns out to be Ben Turpin — who, thanks to his famously crossed eyes, marries Dulcy to the wrong guy.

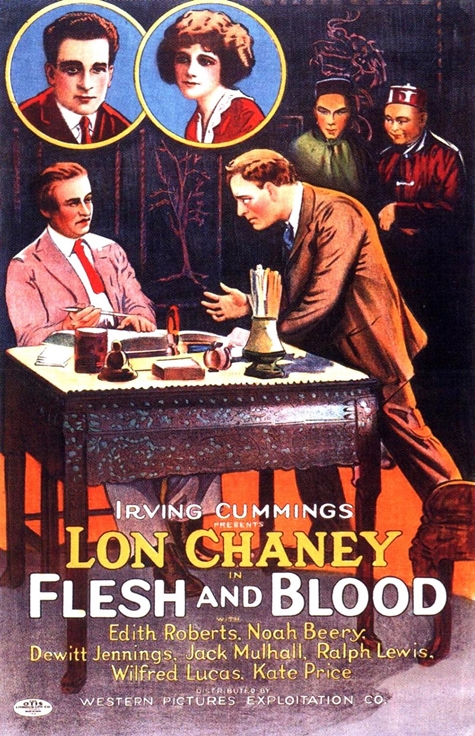

Next it was Flesh and Blood (1922), with Lon Chaney as a man unjustly convicted and imprisoned for a crime he didn’t commit. After 15 years in the joint, he makes an escape to see his wife and daughter, and to find the ex-law-partner who framed him (Ralph Lewis) and force a confession that will clear his name. He is aided in this by a friend in San Francisco’s Chinatown (Noah Beery again, welcome as ever but a little hard to swallow as a Chinese tong lord). Disguised as a wheelchair-bound invalid to elude police, he learns that his wife has died and his daughter, now a beautiful young woman (Edith Roberts), is working in a skid row mission. She believes her father is dead, so he doesn’t disabuse her, but he keeps a watchful eye on her as he plots his revenge. Things get complicated when he learns that his daughter is in love with and engaged to marry the son of his old nemesis (Jack Mulhall).

Lon Chaney is widely regarded today as a horror movie actor, mainly on the strength of The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and The Phantom of the Opera (’25). In fact, in most of his pictures, including those two, lugubrious melodrama was his actual stock in trade. (It took the Andrew Lloyd Webber musical of Phantom to re-assert the fact that Gaston Leroux’s 1910 novel is a romantic melodrama, not a horror story.) Flesh and Blood is a good specimen of that uniquely Lon Chaney brand; it echoed elements in his earlier movies even as it foreshadowed elements of pictures he had yet to make.

There’s some question as to whether the picture survives intact. IMDb gives the running time as 74 min.; in the Exhibitor’s Herald of August 26, 1922 it’s listed at five reels, about the same (in the silent days a picture’s length was expressed in reels, not minutes, due to variations in projector speeds; one reel was roughly 15 minutes). The Picture Show’s print ran 61 min., which was the length of the trimmed-down version offered for rent by Eastman House’s Kodascope Library in the 1920s and ’30s. Quite a few silent movies appear to have survived only in these Kodascope versions (Eastman House having been pioneers in film preservation), and this seems to be one of them. In any case, there are no gaping holes in the picture as it stands; the gang at Eastman Kodak were pretty careful in editing films down for home use, for which we can be grateful.

Flesh and Blood is also noteworthy as an early feature by actor-turned-producer-turned director Irving Cummings; on this one he served in the last two capacities. Cummings would go on to be a hard-working and reliable director, especially at 20th Century Fox. He specialized in musicals, turning out some of the best examples starring Shirley Temple (Curly Top, Poor Little Rich Girl, Little Miss Broadway), Alice Faye (Hollywood Cavalcade, Lillian Russell, That Night in Rio) and Betty Grable (Down Argentine Way, Springtime in the Rockies, The Dolly Sisters), as well as In Old Arizona (taking over for the injured Raoul Walsh) and The Story of Alexander Graham Bell.

Marry Me Again (1953) was lightweight, a bit dated, but pretty dang funny for all that. It starred Robert Cummings and Marie Wilson, both movie veterans just then getting a taste of television success. Wilson had just transferred her hit radio show My Friend Irma to TV (after two movies, in 1949 and ’50) and was America’s favorite lovably ditzy blonde. Cummings was halfway through his first sitcom, the one-season My Hero; his biggest TV success, Love That Bob, was still two years away (which explains why Marie Wilson gets top billing on this poster).

Marry Me Again (1953) was lightweight, a bit dated, but pretty dang funny for all that. It starred Robert Cummings and Marie Wilson, both movie veterans just then getting a taste of television success. Wilson had just transferred her hit radio show My Friend Irma to TV (after two movies, in 1949 and ’50) and was America’s favorite lovably ditzy blonde. Cummings was halfway through his first sitcom, the one-season My Hero; his biggest TV success, Love That Bob, was still two years away (which explains why Marie Wilson gets top billing on this poster).

In Marry Me Again the two play a couple whose wedding is interrupted just short of “I now pronounce you…” when Cummings gets word that he’s been called up for the Korean War. So the wedding goes on a back burner while he jets off to do his bit as a fighter pilot. He comes home a war hero, eager to pick up where he and Wilson left off at the altar. At his welcome-home party, he declares that he intends to be the breadwinner in the family, with his wife staying home where women belong (that sort of thing played better in 1953 than it does now). The problem is, unbeknownst to him, his bride-to-be has inherited a million bucks while he was away. She tries to keep it secret, but the beans get spilled before the wedding. She’s rich, he can’t find a job, so the wedding is off until things get back the way God intended.

Like I say, a bit dated. Still, it was very funny, once you tune in to the fact that the groom-to-be isn’t supposed to be an obnoxious patriarchal jerk. Wilson and Cummings’s comedy chops are considerable, and so are those of writer/director Frank Tashlin. Tashlin was a successful director of cartoon shorts at Warner Bros. who managed the unique feat of transitioning into equal success directing live-action comedies (Son of Paleface, Hollywood or Bust, Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?). Tashlin never lost that Looney Tunes wackiness, and both his cartoons and his movies profited from it.

The first day wrapped up with a diverting low-camp thriller from Monogram, Invisible Ghost (1941). Bela Lugosi played an upstanding citizen living on his country estate with his daughter (Polly Ann Young) and various servants. His one peculiarity is an obsession with the wife who deserted him years ago; now every year on their anniversary he has dinner with her, requiring the butler (Clarence Muse) to serve her empty chair, and talking to her as if she is really there. What he doesn’t know is she is there, wandering the grounds of the estate, brain-damaged, for reasons too complicated to explain. He sees her every once in a while, and when he does he goes into a murderous trance and strangles the first person he sees. His killings have all gone unsolved, and even he doesn’t remember them, but when he murders his maid, who happens to be an ex-girlfriend of his daughter’s fiancé (John McGuire), the fiancé is convicted and executed for the crime. Then the fiancé’s twin (McGuire again) shows up from South America to investigate his brother’s death.

The first day wrapped up with a diverting low-camp thriller from Monogram, Invisible Ghost (1941). Bela Lugosi played an upstanding citizen living on his country estate with his daughter (Polly Ann Young) and various servants. His one peculiarity is an obsession with the wife who deserted him years ago; now every year on their anniversary he has dinner with her, requiring the butler (Clarence Muse) to serve her empty chair, and talking to her as if she is really there. What he doesn’t know is she is there, wandering the grounds of the estate, brain-damaged, for reasons too complicated to explain. He sees her every once in a while, and when he does he goes into a murderous trance and strangles the first person he sees. His killings have all gone unsolved, and even he doesn’t remember them, but when he murders his maid, who happens to be an ex-girlfriend of his daughter’s fiancé (John McGuire), the fiancé is convicted and executed for the crime. Then the fiancé’s twin (McGuire again) shows up from South America to investigate his brother’s death.

It’s all a crock, but somehow director Joseph H. Lewis manages to make something out of this sow’s ear of a script; he draws straight-faced performances from everyone; he (aided by cinematographers Marcel Le Picard and Harvey Gould) enhances the modest sets with atmospheric and expressive (even expressionist) lighting; and he delivers some surprisingly effective chills along the way. Invisible Ghost, all 63 min. of it, is available here on YouTube, if you’re curious. Nine years after giving this Monogram potboiler what conviction it has, Lewis would go on to direct the noir cult classic Gun Crazy (1950).