Cinevent 51 – Prelude

Once again, on the Wednesday night before the first day of Cinevent, some of us early arrivals in Columbus attended a screening at the Wexner Center for the Arts on the Ohio State Campus. The theme this year was “Audrey Hepburn X 2”, and the program consisted of pictures at opposite ends of Audrey’s career, one of her last (Robin and Marian, 1976) followed by one of her first (Secret People, 1952). Personally, I would have preferred that the Wexner Center take the program in chronological order rather than the reverse.

Once again, on the Wednesday night before the first day of Cinevent, some of us early arrivals in Columbus attended a screening at the Wexner Center for the Arts on the Ohio State Campus. The theme this year was “Audrey Hepburn X 2”, and the program consisted of pictures at opposite ends of Audrey’s career, one of her last (Robin and Marian, 1976) followed by one of her first (Secret People, 1952). Personally, I would have preferred that the Wexner Center take the program in chronological order rather than the reverse.

On second thought, let me rephrase that. I would have preferred that they not screen Robin and Marian at all, for one simple reason: It’s lousy. It was lousy in 1976 and it was lousy last Wednesday in Columbus. Besides, if any Ohio State students really needed to see it, Turner Classic Movies has been showing and promoting it for months far beyond its merits.

Purporting to chronicle the last days of Sean Connery’s Robin Hood and Audrey’s Maid Marian, Robin and Marian is easily the worst movie either star ever made — mean-spirited, cheap and shoddy. The mean spirit permeated James Goldman’s sneering script. As for the cheapness, well, there was really no excuse for that. The picture’s budget was $5,000,000 — quite respectable for 1976 — yet it takes place in a twelfth-century England where the population is about 35, all of them dressed in cast-off blankets and tin-plate armor that would be hooted out of any meeting of the Society for Creative Anachronism.

The shoddiness came thanks to the director, the less-than-mediocre Richard Lester, who could never stage the simplest action without zoom-lensing and quick-cutting it into incoherence; without overusing his telephoto lens until his movies looked literally flat; without ham-handed “comedy” that made his actors look like small-time boobs. In a career that ran from 1954 to 1991, Lester made exactly one decent movie — but for many people, that one covered a multitude of sins.

The picture, of course, was A Hard Day’s Night (1964), and Lester got more credit for it than he deserved. When it came out in July ’64 the Beatles were widely regarded as just four lucky yobbos from Liverpool who had stumbled into a freakish fame. Most everyone who wasn’t a teenage girl assumed it would blow over in a year and all four would be moved to the Where Are They Now File. A Hard Day’s Night‘s stars were assumed to be nothing special; in time, of course, the over-21 world would know better, but for now Lester got credit for making the Fab Four so appealing. The picture also had an excellent screenplay by Alun Owen, so smooth it seemed to have been ad-libbed on the spot. Unfortunately for Owen, it suffered the fate of all such scripts: Lester got credit for that too.

But I digress; back to Robin and Marian. Having seen it in 1976, I didn’t care if I never saw it again, but I supposed once every 43 years wouldn’t kill me. Well, now I’m done; if anybody’s still screening this turkey in 2062, I’ll be busy.

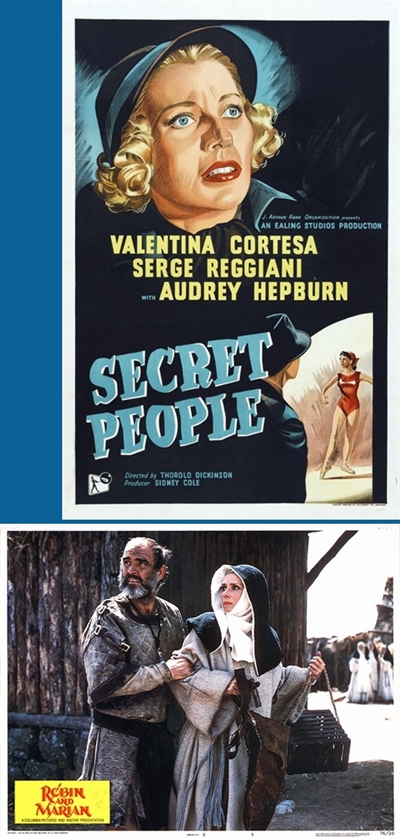

After intermission the Wexner Center redeemed itself with a much worthier effort. Secret People may be remembered chiefly as one of Audrey Hepburn’s first substantial roles (and the one that led directly to her breakthrough in Roman Holiday the next year), but the picture really belongs to Valentina Cortese (or “Cortesa”, as the Brits and Americans preferred to bill her in those days). She and Audrey play Maria Brentano and her younger sister Elenora (Nora), refugees in 1930 from an oppressive dictatorship in their unnamed foreign country. (Their names suggest Mussolini’s Italy, but the dictator is the neutrally-named General Galbern.) Their father, a Gandhi-esque dissident, has smuggled the girls to a friend in London. Shortly after their arrival, they learn that their father has been executed by the Galbern regime.

Seven years later, the two are naturalized British subjects, their surname anglicized to Brent. Maria is unexpectedly reunited with her former boyfriend Louis (Serge Reggiani), who recruits her into a plot to assasinate General Galbern on a visit to London. When the plan goes awry and leads to innocent death, it begins to dawn on Maria that Louis and his cohorts are nothing more than terrorists, as ruthless and callous toward human life as the regime they’re plotting against. Maria’s ambition to be a writer, and Nora’s to be a dancer, mean nothing to them in their lust for blood.

Secret People was directed and co-written by Thorold Dickinson (1903-84), a British filmmaker whose reputation has undergone a bit of a renaissance in recent years. Never prolific (“It’s terribly difficult to direct a film you don’t want to make,” he once said, “that’s why I’ve made so few.”), Dickinson is probably best known over here for his excellent 1940 picture Gaslight, which MGM fortunately failed to destroy when they remade it in 1944. Secret People isn’t entirely successful as either a political thriller or a psychological drama, but it poses intriguing questions, the plot takes some unexpected turns, and Valentina Cortese makes up in screen presence for what the colorless Serge Reggiani lacks. Plus, of course, it offers a glimpse of Audrey Hepburn on the cusp of immortality, indulging her first love, ballet.

In fact, the Audrey Hepburn connection would bear fruit later, once Cinevent itself was under way. I’ll get to that in its own good time.