Cinevent 50 – Day 1

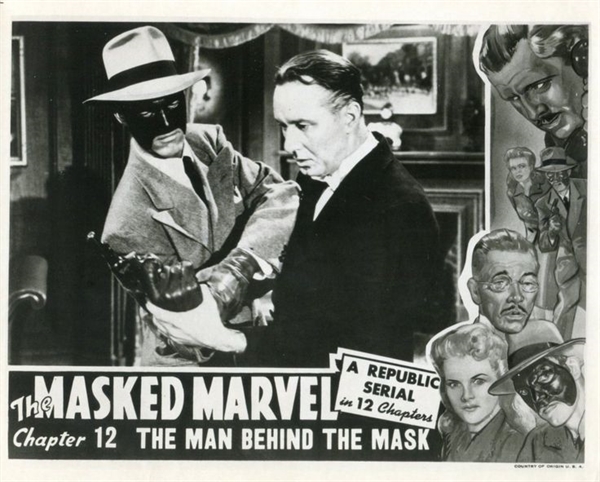

The opening day of Cinevent 50 got underway with the first three chapters of Republic Pictures’ 1943 serial The Masked Marvel, all about efforts to break up a ring of saboteurs led by the Japanese master spy Sakima, played by Johnny Arthur. Arthur is more familiar to audiences, then and now, as Darla Hood’s longsuffering father in Hal Roach’s Our Gang comedies. Seeing the man who could barely cope with Spanky and Alfalfa turning up as the scourge of America’s war effort was a major credulity stretch, to say the least.

The opening day of Cinevent 50 got underway with the first three chapters of Republic Pictures’ 1943 serial The Masked Marvel, all about efforts to break up a ring of saboteurs led by the Japanese master spy Sakima, played by Johnny Arthur. Arthur is more familiar to audiences, then and now, as Darla Hood’s longsuffering father in Hal Roach’s Our Gang comedies. Seeing the man who could barely cope with Spanky and Alfalfa turning up as the scourge of America’s war effort was a major credulity stretch, to say the least.

But The Masked Marvel hardly gave us time to pause over that. This was the kind of opus for which the phrase “action-packed” was coined. Every 20-minute episode abounded in fistfights, gunfights, explosions and car crashes, the latter two courtesy of special-effects wizard Howard Lydecker and his older brother Theodore (what those two boys could accomplish on a budget of approximately nothing was amazing; I really must do a post on them someday).

To heighten the mystery, viewers were invited to figure out just who was the Masked Marvel himself. We were told in the first chapter that he was one of four candidates, but frankly, the suspense was undercut by the fact that they were almost impossible to tell apart, with or without masks. They were played by Rod Bacon, Richard Clarke, David Bacon (no relation to Rod) and Bill Healy — and four blander, less charismatic actors would be hard to imagine.

There’s a grim footnote to all this. By the time the first chapter hit theaters in November 1943, one of the potential Marvels was already dead in real life. On September 12 of that year, David Bacon crashed his car into a beanfield on the then-outskirts of Los Angeles. As a bystander approached, Bacon staggered out of the car and collapsed, hemorrhaging from a knife wound in his back that had pierced his left lung and a lower chamber of his heart. He pleaded weakly for help, then died before he could say who had stabbed him or why. He was 29. The killing was never solved, but while the investigation was ongoing the L.A. papers dubbed it “the Masked Marvel murder”. Whether the moniker was the inspiration of some colorful reporter or a Republic Pictures publicist is probably an unworthy question, so let’s not entertain it, okay?

In his notes for Repeat Performance (1947) in the Cinevent program, and again in introducting the screening, Richard Barrios described the picture as having the kind of premise that tends to lodge in the memory when the picture itself — even the title — is completely forgotten. I can vouch for that, except for the part about forgetting the title. I saw Repeat Performance during its second life on television, maybe 40 years ago, and it certainly stayed with me. Joan Leslie plays a Broadway star who begins 1947 by shooting her husband dead at the stroke of midnight on New Year’s Eve. In an understandable state of shock, she confesses to a poet friend (Richard Basehart in his screen debut), then ruefully wishes she could live the past year over again. Meanwhile, her poet friend — one of those wafty, ethereal types — wishes he’d been the one to have shot her philandering husband (“I would have, you know…”). A moment later she turns around to find the poet is suddenly gone, her clothes are different, and against all reason, it’s New Year’s Eve 1945. The husband she shot (Louis Hayward) is alive and well — though in short order he’ll show himself as a mean, abusive, adulterous drunk who richly deserves killing. Anyhow, the wronged wife’s wish to relive the year has been granted; but will it make any difference?

In his notes for Repeat Performance (1947) in the Cinevent program, and again in introducting the screening, Richard Barrios described the picture as having the kind of premise that tends to lodge in the memory when the picture itself — even the title — is completely forgotten. I can vouch for that, except for the part about forgetting the title. I saw Repeat Performance during its second life on television, maybe 40 years ago, and it certainly stayed with me. Joan Leslie plays a Broadway star who begins 1947 by shooting her husband dead at the stroke of midnight on New Year’s Eve. In an understandable state of shock, she confesses to a poet friend (Richard Basehart in his screen debut), then ruefully wishes she could live the past year over again. Meanwhile, her poet friend — one of those wafty, ethereal types — wishes he’d been the one to have shot her philandering husband (“I would have, you know…”). A moment later she turns around to find the poet is suddenly gone, her clothes are different, and against all reason, it’s New Year’s Eve 1945. The husband she shot (Louis Hayward) is alive and well — though in short order he’ll show himself as a mean, abusive, adulterous drunk who richly deserves killing. Anyhow, the wronged wife’s wish to relive the year has been granted; but will it make any difference?

Repeat Performance was based on a novel by William O’Farrell, with some major changes in Walter Bullock’s script. I’ve sent for a used copy of the book, just to see for myself. In any case, what made it to the screen under Alfred Werker’s efficient direction is a nifty little melodrama; in a way it’s another example of that odd sub-genre I once dubbed “supernatural noir“, and if it’s not quite as memorable as Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1948) or Alias Nick Beal (’49), it’s still pretty good in its own right. Richard Barrios described it, tongue in cheek, as “a film noir version of It’s a Wonderful Life“; a film noir version of Groundhog Day might be a better way to put it. I may have more to say about it after I’ve read O’Farrell’s novel; for now, let’s move on.

Just before the dinner break we saw Sweater Girl (1942), an enjoyable little Paramount “B” musical that just happened to feature one of the greatest song hits of the 1940s: “I Don’t Want to Walk Without You” by Jule Styne and Frank Loesser. The story goes that Loesser and Styne were working on a musical at Poverty Row’s Monogram Pictures when Styne played the melody for his lyricist partner. “Forget about that,” Loesser said. “We won’t waste it here. We’ll take that one to Paramount.” It’s a terrific story and I hate to rain on it, but there’s no record of either Styne or Loesser ever working at Monogram. They did contribute some stock music to the Judy Canova hillbilly comedy Joan of Ozark at Republic. Maybe it was that. (In fact, they both worked at Republic quite a bit from 1940 to ’42, though apparently not together.) Anyhow, whenever Styne may have come up with the melody, they did wait till they were at Paramount to turn it into a song, and by the time Sweater Girl was released in July ’42 the number was a smash hit, recorded by Bing Crosby, Dinah Shore, Vaughn Monroe, and Phil Harris’s Orchestra (vocal by Helen Forrest), among others. It was on every singer’s lips and every drugstore jukebox; Irving Berlin said it was the one song he most wished he’d written. (Remarkably, “I Don’t Want to Walk Without You” was not nominated for an Academy Award, even though there were ten nominees that year, including such utterly forgotten things as “Pig Foot Pete”, “Pennies for Peppino” and “There’s a Breeze on Lake Louise”. Well, it hardly matters. Nineteen-forty-two was the year of “White Christmas”; they could have nominated another hundred songs and none of them would have stood a chance.)

Just before the dinner break we saw Sweater Girl (1942), an enjoyable little Paramount “B” musical that just happened to feature one of the greatest song hits of the 1940s: “I Don’t Want to Walk Without You” by Jule Styne and Frank Loesser. The story goes that Loesser and Styne were working on a musical at Poverty Row’s Monogram Pictures when Styne played the melody for his lyricist partner. “Forget about that,” Loesser said. “We won’t waste it here. We’ll take that one to Paramount.” It’s a terrific story and I hate to rain on it, but there’s no record of either Styne or Loesser ever working at Monogram. They did contribute some stock music to the Judy Canova hillbilly comedy Joan of Ozark at Republic. Maybe it was that. (In fact, they both worked at Republic quite a bit from 1940 to ’42, though apparently not together.) Anyhow, whenever Styne may have come up with the melody, they did wait till they were at Paramount to turn it into a song, and by the time Sweater Girl was released in July ’42 the number was a smash hit, recorded by Bing Crosby, Dinah Shore, Vaughn Monroe, and Phil Harris’s Orchestra (vocal by Helen Forrest), among others. It was on every singer’s lips and every drugstore jukebox; Irving Berlin said it was the one song he most wished he’d written. (Remarkably, “I Don’t Want to Walk Without You” was not nominated for an Academy Award, even though there were ten nominees that year, including such utterly forgotten things as “Pig Foot Pete”, “Pennies for Peppino” and “There’s a Breeze on Lake Louise”. Well, it hardly matters. Nineteen-forty-two was the year of “White Christmas”; they could have nominated another hundred songs and none of them would have stood a chance.)

Aside from showcasing “I Don’t Want to Walk Without You” — which it does very adroitly, the boys at Paramount knowing gold when they hear it — Sweater Girl was an amusing hybrid of murder mystery and hey-kids-let’s-put-on-a-show college musical, a remake of 1935’s College Scandal. It elevated Eddie Bracken from comic support to leading man (albeit in a B picture), preparing him for his apotheosis under Preston Sturges. Between Styne and Loesser’s sprightly songs, Bracken shared detective duties with perky June Preisser, who was winding down from her own apotheosis as the girl who almost wins Mickey Rooney away from Judy Garland in Babes in Arms (1939) and Strike Up the Band (1940). Vocal assignments on the movie’s biggest hit went to nightclub singer Johnny Johnston as the song’s ostensible composer (who gets strangled mid-chorus while demo-ing the song over shortwave radio) and Betty Jane Rhodes as the campus queen. (Rhodes and Johnston would later be teamed in a number of Paramount’s wartime morale-builders, where they were quite popular for a time on the home front.)

These were the highlights of the first day for me — in the screening room, that is. Outside the screening room, there was the Golden Celebration Reception on Thursday evening around the Renaissance Hotel’s pool. The inset on the left shows one of the three cakes for the occasion. In the right inset, my friend Phil Capasso is shown introducing special guest Leonard Maltin. Phil earned this privilege by virtue of being the only person to have attended all fifty Cinevents since the first one way back in 1969. (Phil got the first slice of cake, too.)

These were the highlights of the first day for me — in the screening room, that is. Outside the screening room, there was the Golden Celebration Reception on Thursday evening around the Renaissance Hotel’s pool. The inset on the left shows one of the three cakes for the occasion. In the right inset, my friend Phil Capasso is shown introducing special guest Leonard Maltin. Phil earned this privilege by virtue of being the only person to have attended all fifty Cinevents since the first one way back in 1969. (Phil got the first slice of cake, too.)

After that it was back to the screening room, where Scott Eyman spoke in conjunction with his latest book Hank and Jim: The Fifity-Year Friendship of Henry Fonda and James Stewart, then introduced Fonda and Stewart’s episode from On Our Merry Way (1948), an omnibus film produced by and starring Burgess Meredith, their erstwhile roommate from their starving-actor days in New York. The two were teamed as down-at-heels musicians trying to put on a music competition in a podunk town to get their band’s bus out of hock. Directed without credit by George Stevens, the episode is generally recognized as the best part of that rather lackluster feature. Then came Four Around a Woman (1921), an early silent melodrama from German director Fritz Lang; the print shown had German intertitles which were (fortunately!) translated aloud by Glory-June Greiff. Finally, it was the British police procedural The Third Key (UK title The Long Arm; 1956), with Jack Hawkins as a Scotland Yard inspector on the trail of a serial safecracker. And with that tidy little suspenser, we all called it a day.