Picture Show No. 3 — Tying Off a Loose End

Day 1 — Continued

So…Where was I? Oh Yes, Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928). As I said last time, Buster Keaton’s last masterpiece would be a highlight of any weekend of classic movies, and so it was in Columbus this year. This is the picture with one of the most famous stunts of the silent era — or any era since, for that matter — where the whole side of a house collapses on Buster during a cyclone, with only an open window saving him from being smashed flat.

So…Where was I? Oh Yes, Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928). As I said last time, Buster Keaton’s last masterpiece would be a highlight of any weekend of classic movies, and so it was in Columbus this year. This is the picture with one of the most famous stunts of the silent era — or any era since, for that matter — where the whole side of a house collapses on Buster during a cyclone, with only an open window saving him from being smashed flat.

I used to screen Steamboat Bill, Jr. for my Film Studies classes at a local community college here in Sacramento, not only because it’s a masterpiece, but for a local connection to which my students could relate: Keaton shot the picture on the outskirts of Sacramento, building his fictitious town of River Junction on the west bank of the Sacramento River (doubling for the Mississippi), just above its confluence with the American River. The opening shot, panning from the American to the Sacramento and the River Junction set, is instantly recognizable to local residents today — if they can imagine the wide swath of Interstate 5 bisecting the frame.

I used to screen Steamboat Bill, Jr. for my Film Studies classes at a local community college here in Sacramento, not only because it’s a masterpiece, but for a local connection to which my students could relate: Keaton shot the picture on the outskirts of Sacramento, building his fictitious town of River Junction on the west bank of the Sacramento River (doubling for the Mississippi), just above its confluence with the American River. The opening shot, panning from the American to the Sacramento and the River Junction set, is instantly recognizable to local residents today — if they can imagine the wide swath of Interstate 5 bisecting the frame.

Also recognizable, though less immediately apparent, is the building just visible on the horizon in this frame cap, between Buster and his leading lady, the fetching Marion Byron. It’s almost unnoticeable watching the movie, and not easy to make out even here. So here, below the full frame, is an enlargement of a section of it. See it now? Author John Bengston, in his book Silent Echoes: Discovering Early Hollywood Through the Films of Buster Keaton, cites Paul Frobose of the Sacramento County Historical Society as identifying the building as the former California State Insurance Building at 10th and J Streets in Sacramento, three blocks from the State Capitol.

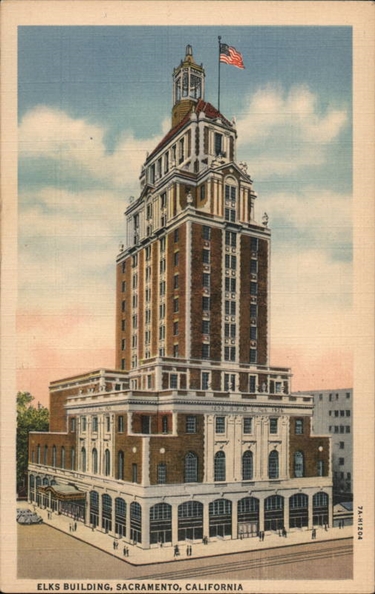

But I think a likelier candidate is this one on the left, Sacramento’s Elks Building, one block east at 11th and J. Recently completed in 1928, it was then the tallest building in Sacramento, the first one taller than the Capitol. Both the Elks and Insurance Buildings are still standing, but it’s too late to resolve the issue now; even if we could identify the exact spot where Keaton and director Charles Reisner placed their camera, too many newer, taller buildings have sprung up, on both sides of the river, in the 97 years since Buster and Marion stood there thinking wistfully of each other.

But I think a likelier candidate is this one on the left, Sacramento’s Elks Building, one block east at 11th and J. Recently completed in 1928, it was then the tallest building in Sacramento, the first one taller than the Capitol. Both the Elks and Insurance Buildings are still standing, but it’s too late to resolve the issue now; even if we could identify the exact spot where Keaton and director Charles Reisner placed their camera, too many newer, taller buildings have sprung up, on both sides of the river, in the 97 years since Buster and Marion stood there thinking wistfully of each other.

Among its many pleasures, Steamboat Bill, Jr. is also notable for giving character actor Ernest Torrence a rare opportunity to exercise his comic chops as Steamboat Bill Sr. At a towering six-foot-four, just seeing him standing next to the 5′ 5″ Keaton is already hilarious, but Torrence had a real flair for comedy that he too seldom got to deploy in a career where his size usually had him in more serious, even menacing roles — though he was also an extremely funny Captain Hook to Betty Bronson’s Peter Pan in 1924 (screened at Cinevent in 1999). He easily made the transition to sound, but an infection after gall bladder surgery in 1933 carried him off at 54; if he’d been granted even another ten or 15 years he might well have given Donald Crisp a run for his money.

My film studies students were usually unfamiliar with Steamboat Bill, Jr. — most of them were even unfamiliar with Keaton — but nearly all of them knew Walt Disney’s Steamboat Willie. So they got that little light bulb of discovery when I pointed out that the title of Disney’s first Mickey Mouse cartoon was a play on the title of Keaton’s picture. “If you ever wondered why he didn’t call it Steamboat Mickey…well, now you know.”

Next came the first sound version of Henry De Vere Stacpoole’s 1908 novel The Blue Lagoon (1949), with Susan Stranks and Peter Rudolph James as children shipwrecked on a South Pacific island who grow up into Jean Simmons and Donald Houston, fall in love, and innocently found a family before being discovered by two other castaways (James Hayter, Cyril Cusack) of unsavory backgrounds and intentions. In Stacpoole’s novel, the two kids are first cousins, but this 1949 production bowed to the dictates of the Breen Office by removing any hint of incest and forgoing the nudity and overt eroticism that would later characterize the 1980 remake with Brooke Shields and Christoper Atkins. Photographed in beautiful Technicolor, director Frank Launder’s version hewed closely to Stacpoole’s idyllic Adam-and-Eve-in-the-Garden-of Eden theme. Audiences at the time, like later ones in 1980 (and presumably those of the lost 1923 silent picture), were left to wonder why the young man never grows a beard and the young woman’s legs and underarms remain primly shaved throughout their long desert-island sojourn. Perhaps beguiled by the beauty of Simmons and Houston in their winsome young-adult prime, nobody seemed to mind; they certainly didn’t in Columbus.

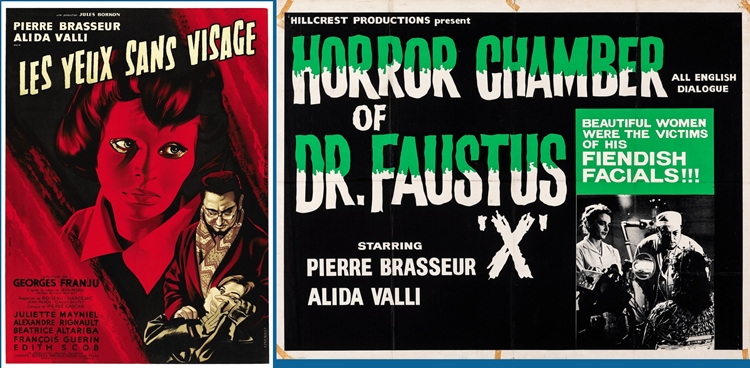

Day 1 rounded off with a late-night screening of a 1960 European horror film, as it had last year with Mario Bava’s Black Sunday. This year the program book promised us the French shocker Eyes Without a Face (French title: Les yeux sans visage) from director Georges Franju, the tale of a mad scientist (Pierre Brasseur) who tries, repeatedly and without success, to repair his daughter’s (Édith Scob) disfigured face by transplanting those of luckless young women kidnapped by his assistant (Alida Valli). After each failure, the victim’s mangled remains are then dumped where the ghoulish pair hope they’ll never be found. Eventually, the doctor’s daughter goes mad herself and wreaks a terrible vengeance.

Day 1 rounded off with a late-night screening of a 1960 European horror film, as it had last year with Mario Bava’s Black Sunday. This year the program book promised us the French shocker Eyes Without a Face (French title: Les yeux sans visage) from director Georges Franju, the tale of a mad scientist (Pierre Brasseur) who tries, repeatedly and without success, to repair his daughter’s (Édith Scob) disfigured face by transplanting those of luckless young women kidnapped by his assistant (Alida Valli). After each failure, the victim’s mangled remains are then dumped where the ghoulish pair hope they’ll never be found. Eventually, the doctor’s daughter goes mad herself and wreaks a terrible vengeance.

What we saw, in fact, wasn’t Franju’s French original, but the edited (by about two minutes) and English-dubbed version released in the U.S. in 1962 by Lopert Films under the insanely nonsensical title Horror Chamber of Dr. Faustus. Either way, it’s a stylish (if such an adjective can be applied to such grisly subject matter) and effective chiller, highlighted by a startling, can’t-look-away scene of the obsessed “Dr. Faustus” (actually “Dr. Génessier”) at work in his operating room, his scalpel peeling a young woman’s face away from her skull. This scene had audiences in the 1960s (my teenage self included) either staring aghast or averting their eyes in horror, and the scene — the whole film — has lost none of its punch. The French original is available here on YouTube, and it shows up on Turner Classic Movies from time to time.

* * *

That’s as far as I got on this post, back in June, when its original title was “Picture Show No. 3 — Day 1, Part 2”. Then, as I warned at the end of “Day 1, Part 1”, my coverage of the 2024 Columbus Moving Picture Show (May 23-26, 2024) was interrupted by previously scheduled vacation travels. I promised to resume as soon as possible, but I reckoned without — how do I put this? — an unexpected medical issue that arose in the midst of those travels and was allowed to deepen and worsen while I flew hither and yon, leading eventually to emergency surgery, a week in hospital, home infusions of antibiotics four times a day for six weeks, and a longer, slower recovery than I could possibly have expected.

That’s all I’ll say about that — there’s nothing more boring than hearing about somebody else’s operation — but the upshot of it all is that last May’s Picture Show weekend has grown less fresh in my memory — and besides, it’s old news now anyway. (Memo to self: You really must start taking detailed notes while you’re on the spot in Columbus.)

My usual detailed rundown of the Picture Show weekend is no longer feasible — and possibly no longer of interest — but just for the record, here are some highlights of Days 2, 3 and 4:

Day 2

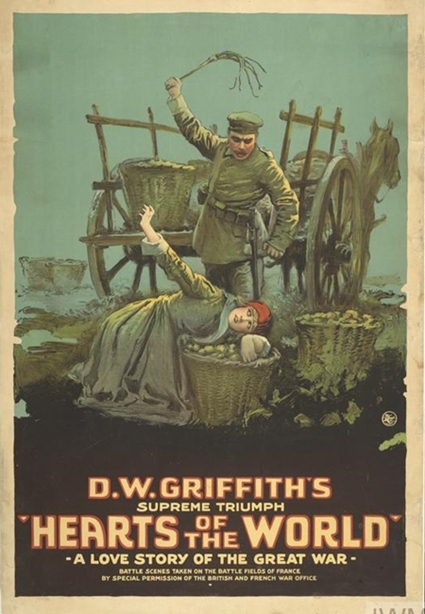

Three silent pictures — two renowned classics and one a bit of a rediscovered surprise — highlighted the remaining days of the Picture Show. First was Hearts of the World (1918), D.W. Griffith’s melodrama of The Great War. Griffith’s story told of The Girl (Lillian Gish) and The Boy (Robert Harron) separated on the eve of their wedding by the outbreak of war. The Girl wanders deranged on the battlefield, then is nursed back to sanity by The Little Disturber (a showcase role for Lillian’s sister Dorothy). Griffith’s hand with battle action and a desperate-dash-to-the-rescue climax, like his penchant for cloying character names, was as strong as ever. But his timing was beginning to falter: Just as his pacifist message in Intolerance (1916) had fallen on blind eyes with America gearing up to enter the war, his hate-the-Hun militarism was inconvenient now that the war was all but over and the Allies were looking to patch things up at Versailles.

Day 3

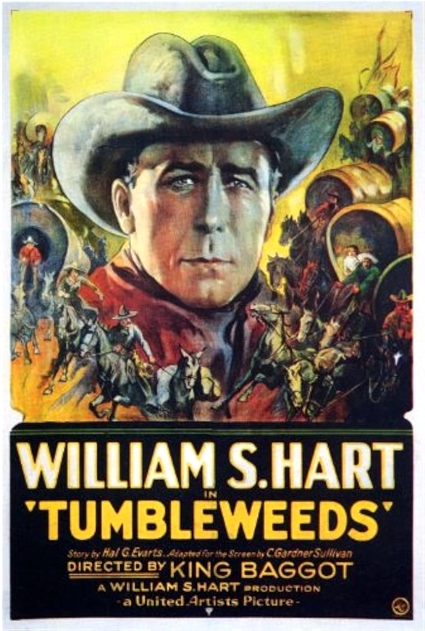

Tumbleweeds (1925) was western icon William S. Hart’s last hurrah — indeed, except for a cameo in the King Vidor/Marion Davies Show People (1928) and a wistful spoken prologue to a 1939 reissue of Tumbleweeds, it was his last film appearance ever. The old boy certainly went out in style. Tumbleweeds is among his best, climaxed by a rousing recreation of the 1893 Oklahoma Land Rush and featuring some horsemanship by the 60-year-old Hart that still makes men half his age gape in wonder. With a face that virtually personified the Old West, he was an icon indeed; with the exception of Owen Wister in his 1902 novel The Virginian, Hart had more to do with the creation of the archetypal Westerner than anbody. His understated acting and unerring eye for realistic frontier detail give his pictures the ring of truth even now, when most of them are more than a century old — further in the past, in fact, than the genuine Old West was when they were made. Later stars from Gary Cooper and John Wayne, through Randolph Scott and Joel McCrea, to Clint Eastwood and Kevin Costner, can all thank William S. Hart that they even had careers.

Tumbleweeds (1925) was western icon William S. Hart’s last hurrah — indeed, except for a cameo in the King Vidor/Marion Davies Show People (1928) and a wistful spoken prologue to a 1939 reissue of Tumbleweeds, it was his last film appearance ever. The old boy certainly went out in style. Tumbleweeds is among his best, climaxed by a rousing recreation of the 1893 Oklahoma Land Rush and featuring some horsemanship by the 60-year-old Hart that still makes men half his age gape in wonder. With a face that virtually personified the Old West, he was an icon indeed; with the exception of Owen Wister in his 1902 novel The Virginian, Hart had more to do with the creation of the archetypal Westerner than anbody. His understated acting and unerring eye for realistic frontier detail give his pictures the ring of truth even now, when most of them are more than a century old — further in the past, in fact, than the genuine Old West was when they were made. Later stars from Gary Cooper and John Wayne, through Randolph Scott and Joel McCrea, to Clint Eastwood and Kevin Costner, can all thank William S. Hart that they even had careers.

Day 4

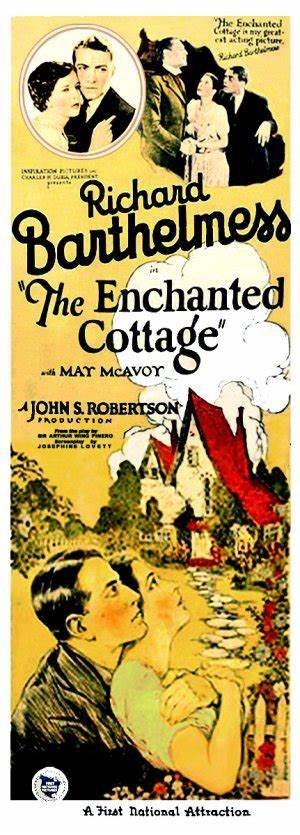

A third silent on Day 4 is what stands out in my memory at this remove. This was The Enchanted Cottage (1924), the first screen version of Arthur Wing Pinero’s 1921 play. The play dealt with the fortuitous relationship that develops between a badly maimed veteran of The Great War (Richard Barthelmess) who banishes himself to a remote cottage to spare his family the sight of him, and a plain — even downright ugly — local girl (May McAvoy) who tends the cottage. In time, the spell of the cottage, and of the generations of newlyweds who have resided there, overcomes them and they see the sensitivity and inner beauty in themselves and each other, and the knowledge transforms them — if only in their own eyes — into the loving people they truly are.

A third silent on Day 4 is what stands out in my memory at this remove. This was The Enchanted Cottage (1924), the first screen version of Arthur Wing Pinero’s 1921 play. The play dealt with the fortuitous relationship that develops between a badly maimed veteran of The Great War (Richard Barthelmess) who banishes himself to a remote cottage to spare his family the sight of him, and a plain — even downright ugly — local girl (May McAvoy) who tends the cottage. In time, the spell of the cottage, and of the generations of newlyweds who have resided there, overcomes them and they see the sensitivity and inner beauty in themselves and each other, and the knowledge transforms them — if only in their own eyes — into the loving people they truly are.

I was familiar with the story only through the 1945 remake, updated to World War II and starring Dorothy Maguire and Robert Young. That version has always struck me as rather sickly-sentimental in a treacly Victorian way, and I found the lovers’ “ugly” sides — amounting to a couple of unfortunate scars on Robert Young and thick eyebrows and a shoddy dress on Dorothy Maguire — a bit of a tempest in a teapot, as if director John Cromwell and RKO Radio were unwilling to make their stars look really bad. Curiously enough, the 1924 silent (directed by John S. Robertson), by jumping into the Victorian sentimentality with both feet — and not least, by fearlessly making stars Barthelmess and McAvoy truly, well, unfortunate — gives the story a conviction that the remake lacks. The remake also lacks the play’s scenes in which the modern-day lovers are visited by the ghosts of honeymooners from centuries past; this silent version, made while the play was still treading the boards in regional theaters, includes those fantasy elements, and in so doing it better preserves and presents the enchantment promised by the title. The Enchanted Cottage (’24) is wholly superior to its better-known remake, and as one who has always found the remake completely resistible, I was pleasantly surprised.

There were other highlights of Picture Show Weekend that should not go unmentioned. A lovely Technicolor print of Green Grass of Wyoming (1948), a sort of second sequel to My Friend Flicka (1943) in the boy-and-his-horse genre. Though set in Wyoming, the green grass in this case was actually in Utah, and the Picture Show screening was introduced by historian James D’Arc, who was also there signing copies of the new Centennial Edition of his authoritative tome When Hollywood Came to Utah, commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Beehive State’s career as a film and TV location. Then also, the customary samplings of comedy shorts from Max Davidson, Charley Chase and Laurel and Hardy. Angel’s Holiday (1937), with Jane Withers her usual impish self, a sort of live-action version of Little Lulu. And speaking of Little Lulu, one of Lulu’s cartoons, A Scout with the Gout, was a major part of Stewart McKissick’s annual Saturday morning Animation Program (like Stewart, I hope someday those Little Lulu cartoons, with their irresistible theme song, become available on home video). Slightly French (1949), a Columbia musical from director Douglas Sirk with Don Ameche and Dorothy Lamour ringing amusing changes on the Pygmalion theme. Take a Chance (1933), a Paramount Pre-Code musical with James Dunn, June Knight, “It’s Only a Paper Moon” and Lilian Roth doing a red-hot carnival dance previewed by Richard Barrios among his musical clips on Day 1. And, of course, the remaining chapters of the Spy Smasher serial, right up to the final triumph of the Good Guys in Chapter 12.

Sorry I can’t go into any further detail on the program as it played last May. You just had to be there. Now, for us here at Cinedrome, on to other things…