“Is Virginia Rappe Still Alive?”

Short answer: Nope. Dead as a doornail since 101 years ago last month.

Short answer: Nope. Dead as a doornail since 101 years ago last month.

See, I can make that joke because Virginia Rappe has been dead that long, and everybody who knew her, and who might take offense at my flippancy, has followed her into that undiscovered country from which no traveler returns.

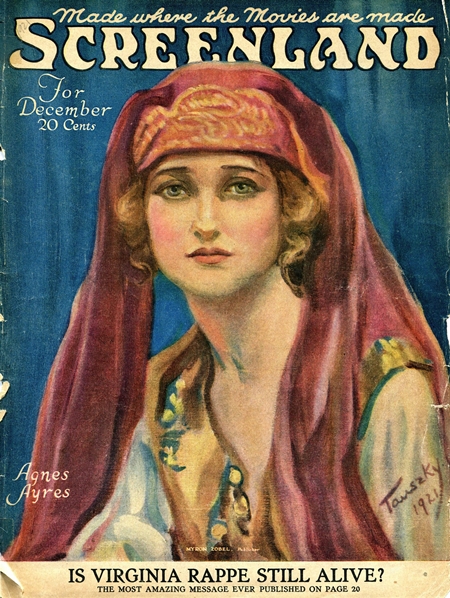

But what about when this article was published in the December 1921 issue of Screenland Magazine? When it hit the stands in November, Virginia was only two months in her grave. Did anybody in the Screenland offices, or any of her friends and acquaintances in Los Angeles, Chicago (where she was born in 1891) or San Francisco (where she lived during 1916 before moving south) — did any of them detect the tone of morbid humor in that title and cry, “Too soon! Too soon!”?

I probably don’t need to explain to most Cinedrome readers who Virginia Rappe was, but just in case, here’s a quick rundown. Born Virginia Rapp in 1891 in Chicago, her mother died when she was 11, leaving her to be raised by her grandmother (Virginia, born out of wedlock, had her mother’s surname; her biological father, allegedly a prominent and married Chicago socialite, was never in the picture). As a teenager she found work as an artist’s model, and that appears to be when she added the sounded “e” at the end of her name for an exotic touch (she also sometimes went by Virginia Rappae). It was modeling that led her to move to San Francisco, where she not only earned a comfortable living, but became engaged to a dress designer named Robert Moscovitz — until he was killed in a streetcar accident. An opportunity to enter moving pictures took her to Los Angeles, where she landed occasional work while living with — and reputedly being engaged to — producer/director Henry Lehrman. Some stories also have her living in New York for a while and gallivanting around Europe at some time or other. Maybe so.

Anyhow, it all ended for Virginia three weeks after the release of her last picture, the comedy short The Misfit Pair, when she attended a Labor Day 1921 party in the suite of superstar Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle in San Francisco’s St. Francis Hotel. In the ever-present defiance of Prohibition, liquor flowed freely, and exactly what happened at the party has never been clear, probably not even in the booze-fogged memories of several who were there and later testified. What is known for sure is that sometime around 3:00 p.m. that Monday, Virginia became violently ill and began tearing at her clothes. Several of those present tried to soothe her with various home remedies, and finally the hotel doctor was summoned. He diagnosed a case of extreme intoxication, and he — or maybe somebody else; like so much of the story, that detail isn’t clear — administered a shot of morphine for her pain. She was moved to another room at Arbuckle’s expense; assured that she would be all right in a day or two, Arbuckle checked out on Tuesday and went home to Hollywood. This picture of the party suite offers mute testimony that today’s hotel-trashing rock musicians have nothing on partying Prohibition movie stars — although to be fair, we don’t know who took the picture, or when, or whether any of the damage happened after the party broke up.

Anyhow, it all ended for Virginia three weeks after the release of her last picture, the comedy short The Misfit Pair, when she attended a Labor Day 1921 party in the suite of superstar Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle in San Francisco’s St. Francis Hotel. In the ever-present defiance of Prohibition, liquor flowed freely, and exactly what happened at the party has never been clear, probably not even in the booze-fogged memories of several who were there and later testified. What is known for sure is that sometime around 3:00 p.m. that Monday, Virginia became violently ill and began tearing at her clothes. Several of those present tried to soothe her with various home remedies, and finally the hotel doctor was summoned. He diagnosed a case of extreme intoxication, and he — or maybe somebody else; like so much of the story, that detail isn’t clear — administered a shot of morphine for her pain. She was moved to another room at Arbuckle’s expense; assured that she would be all right in a day or two, Arbuckle checked out on Tuesday and went home to Hollywood. This picture of the party suite offers mute testimony that today’s hotel-trashing rock musicians have nothing on partying Prohibition movie stars — although to be fair, we don’t know who took the picture, or when, or whether any of the damage happened after the party broke up.

Virginia, alas, did not get better. By Thursday she had been hospitalized at the private Wakefield Sanitarium in San Francisco, and by Friday she was dead, age 30, done in by a ruptured bladder and resulting peritonitis (a serious killer in those pre-antibiotic days). It later came out that Virginia had suffered from a chronic bladder condition since at least 1913, possibly — though not necessarily — from one or more illegal abortions she had undergone over the years.

So much for the undisputed facts. At this point, two real-piece-of-work characters enter the story — three, if you count William Randolph Hearst, who sensationalized the case as a way of exploiting Hollywood’s “immorality” while diverting attention from his own relationship with Marion Davies. The first piece of work was a woman named Bambina “Maude” Delmont, who came to the party with Virginia. Early on, already drunk, she disappeared into a bedroom with Arbuckle’s suite-mate Lowell Sherman, locking the door. She didn’t emerge until after Virginia fell ill, but then she stayed with her to the end, after which she swore out a complaint accusing Arbuckle of raping and murdering Virginia.

The second was San Francisco District Attorney Matthew A. Brady. Intensely — even unscrupulously — ambitious, Brady believed he could ride the Arbuckle case all the way to the Governor’s Mansion in Sacramento. Early on, he hit a few snags. For one thing, a post-mortem examination of poor Virginia by doctors at the sanitarium was inconclusive as to whether she had been assaulted, physically or sexually. Worse, Maude Delmont, Brady’s accusing witness, had testified before the San Francisco Coroner’s Court, leading to Arbuckle’s indictment, but she was useless as a trial witness. She had a police record for prostitution, extortion and blackmail, running “the old Badger Game”, setting up marks (the more famous the better) in compromising situations, then shaking them down to keep the story quiet. She had even wired two lawyers in L.A. and San Diego as soon as Virginia died, crowing that she had Arbuckle “in a hole here[,] chance to make some money out of him”. Brady was in a spot; in those days, police and prosecutors didn’t feel the need to use words like “suspect”, “alleged” or “accused” when discussing cases, and he had shot his big mouth off about Arbuckle’s guilt; he couldn’t back down now. While he didn’t hesitate to bully witnesses, suborn perjury, and even — perhaps — falsify fingerprint evidence, he didn’t dare put Delmont on the stand; her background was too unsavory, and there were too many discrepancies between the complaint she’d sworn out with the cops and the one time she did testify at the coroner’s inquest. Brady knew she wouldn’t last five minutes under cross-examination.

The second was San Francisco District Attorney Matthew A. Brady. Intensely — even unscrupulously — ambitious, Brady believed he could ride the Arbuckle case all the way to the Governor’s Mansion in Sacramento. Early on, he hit a few snags. For one thing, a post-mortem examination of poor Virginia by doctors at the sanitarium was inconclusive as to whether she had been assaulted, physically or sexually. Worse, Maude Delmont, Brady’s accusing witness, had testified before the San Francisco Coroner’s Court, leading to Arbuckle’s indictment, but she was useless as a trial witness. She had a police record for prostitution, extortion and blackmail, running “the old Badger Game”, setting up marks (the more famous the better) in compromising situations, then shaking them down to keep the story quiet. She had even wired two lawyers in L.A. and San Diego as soon as Virginia died, crowing that she had Arbuckle “in a hole here[,] chance to make some money out of him”. Brady was in a spot; in those days, police and prosecutors didn’t feel the need to use words like “suspect”, “alleged” or “accused” when discussing cases, and he had shot his big mouth off about Arbuckle’s guilt; he couldn’t back down now. While he didn’t hesitate to bully witnesses, suborn perjury, and even — perhaps — falsify fingerprint evidence, he didn’t dare put Delmont on the stand; her background was too unsavory, and there were too many discrepancies between the complaint she’d sworn out with the cops and the one time she did testify at the coroner’s inquest. Brady knew she wouldn’t last five minutes under cross-examination.

Incredible as it sounds to us today, when high-profile trials can drag on for years, even decades, Arbuckle stood trial three times between November 1921 and April ’22. After two hung juries, the third jury deliberated six minutes before acquitting him — five of which were spent drafting an unprecedented apology that he had ever been charged in the first place. Nonetheless, Arbuckle’s career was wrecked. Like later blacklisted celebrities, he eked out a living off-screen under an alias throughout the ’20s, and he was on the verge of a comeback in 1933 when a heart attack carried him off in his sleep at 46. (On a side note, the scoundrel Brady’s career didn’t exactly flourish. He stalled out at D.A. of San Francisco, the poster boy for malicious prosecution and misconduct. In a delicious irony, he never made it to the Governor’s Mansion, but the man who finally unseated him in 1943, Edmund G. “Pat” Brown, did.)

So there, in a hasty six paragraphs, is a summary of why Virginia Rappe’s name was a headline in the December 1921 issue of Screenland Magazine: “Is Virginia Rappe Still Alive?” Beyond that, I’m not going to rehash the case here; it’s fascinating but way too complicated, fascinating and complicated enough to have provided fodder for several books; go to Amazon and run a search in Books for “Fatty Arbuckle Case” and you’ll find several examples (I can personally recommend The Day the Laughter Stopped by David Yallop [1976]; it’s out of print but still available used or on Kindle. Others, more recent, look interesting, but I haven’t read them). My subject today isn’t the case, but the Screenland article, illustrating as it does a peculiar intersection of spiritualism, yellow journalism, and celebrity culture.

So there, in a hasty six paragraphs, is a summary of why Virginia Rappe’s name was a headline in the December 1921 issue of Screenland Magazine: “Is Virginia Rappe Still Alive?” Beyond that, I’m not going to rehash the case here; it’s fascinating but way too complicated, fascinating and complicated enough to have provided fodder for several books; go to Amazon and run a search in Books for “Fatty Arbuckle Case” and you’ll find several examples (I can personally recommend The Day the Laughter Stopped by David Yallop [1976]; it’s out of print but still available used or on Kindle. Others, more recent, look interesting, but I haven’t read them). My subject today isn’t the case, but the Screenland article, illustrating as it does a peculiar intersection of spiritualism, yellow journalism, and celebrity culture.

Here, just to show that it was a headline inside and out, is the cover of that issue of Screenland, featuring that same question about Virginia’s survival that spreads across pp. 20-21 inside. The question, which hit the stands midway through Roscoe Arbuckle’s first trial, is deliberately provocative, slyly hinting that Virginia may be hiding out somewhere, watching from a distance as Roscoe squirms in the dock.

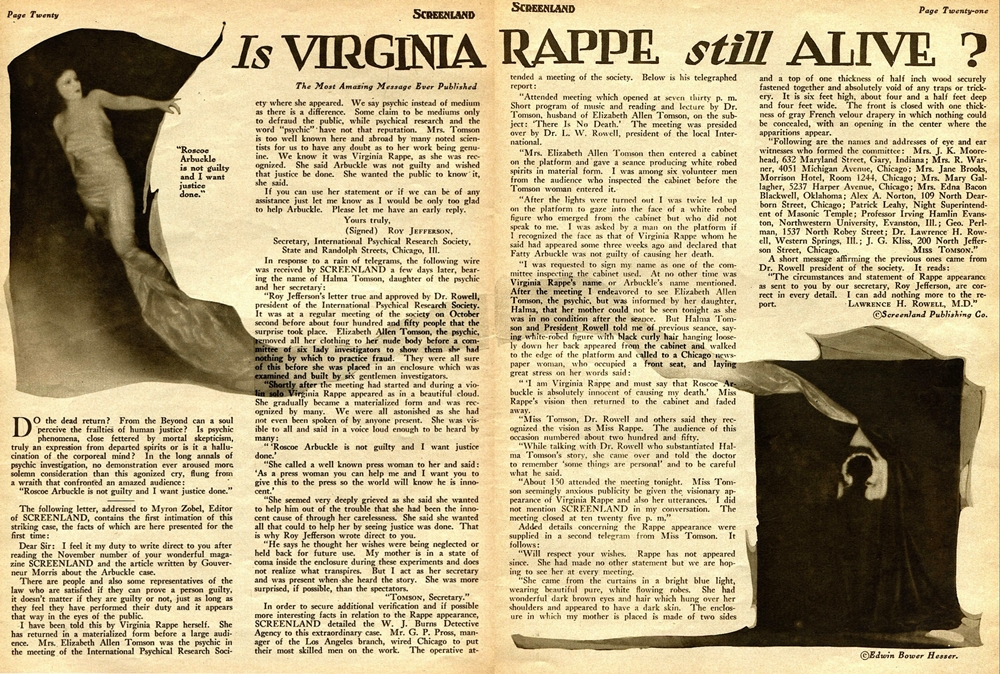

But no, it’s just a come-on, designed to get readers browsing the newsstand or drugstore magazine rack to plunk down their dimes. The “survival” implied was spiritual, not physical. The article is reproduced above in its entirety; depending on the size and resolution of your monitor, you may be able to read it. In case you can’t, here’s a rundown of what it says:

Under the sub-head “The Most Amazing Message Ever Published”, the article reprints a letter to Screenland editor Myron Zobel from one Roy Jefferson, Secretary of the International Psychical Research Society (IPRS), located at State and Randolph Streets in Chicago. Mr. Jefferson is writing in response to an article in the previous month’s Screenland about the Arbuckle case, written by Gouverneur Morris.

Now here, a sidebar. Having read that much, I assumed that “Gouverneur Morris” must be a pseudonym adopted by some employee of the magazine, a cub reporter or intern (or whatever they called office interns in the 1920s). But no, he was a real person — actually, Gouverneur Morris IV (1876-1953), great-grandson of the signer of the Declaration of Independence, and a prolific writer of pulp novels and short stories, several of which were filmed over the years. Morris was about 45 in 1921. It would be interesting to know what he wrote about the Arbuckle case at that early date, but unfortunately my digital Screenland archive doesn’t include that particular issue.

Anyhow, whatever Morris wrote, it was interesting enough to prompt Roy Jefferson to write, and to assert that Roscoe Arbuckle was innocent. Now remember, this was barely two months after the party at the St. Francis; Roscoe was being denounced from every pulpit in America and vilified in every newspaper in the world. It took a certain amount of nerve to stand against that tsunami of public opinion, so let’s give credit where it’s due. Roy Jefferson was firm in his faith in Roscoe’s innocence, and no wonder: He claimed that he heard it from Virginia Rappe herself, and that she wanted justice to be done. This happened, he said, at a meeting of the IPRS, facilitated by the “psychic” Elizabeth Allen Tomson (they preferred the word “psychic” to “medium”, Jefferson wrote, because self-described mediums were often frauds, while psychics were serious researchers).

When the Screenland editors followed up by mail, they got a reply from Halma Tomson, Mrs. Tomson’s daughter and secretary, confirming what Jefferson had written — Virginia manifested herself on October 2 at a meeting of the IPRS attended by some 450 people. Mrs. Tomson, having stripped to the skin and been examined for any fakery by a committee of six ladies, was “placed in an enclosure which was examined and built by six gentlemen [sic] investigators.”

“Shortly after the meeting had started and during a violin solo Virginia Rappe appeared as in a beautiful cloud. She gradually became a materialized form and was recognized by many. We were all astonished as she had not even been spoken of by anyone present. She was visible to all and said in a voice loud enough to be heard by many:

“‘Roscoe Arbuckle is not guilty and I want justice done.’

“…My mother is in a state of coma inside the enclosure during these experiments and does not realize what transpires. But I act as her secretary and was present when she heard the story. She was more surprised, if possible, than the spectators.”

I’m sure she was. And what a lucky coincidence that in Virginia’s native city, where she hadn’t lived since at least 1913, there were “many” people in the audience who were able to confirm her identity.

When a person materializes from The Other Side in front of an audience of 450, through a “psychic” who has been privately examined nude by six women (proving that she has, ahem, nothing up her sleeve) and placed in a cabinet that has been assembled and examined for any trickery by six other volunteers — and all this accompanied by a violin solo, no less — we’re not talking about your usual séance, much less an actual scientific “experiment”. What we have here is a magic show — what magicians to this day call “the spirit cabinet”.

Is it possible that the showbiz-savvy editors of Screenland didn’t see through these vaudeville monkeyshines? They must have done, and no doubt knowing a great hook when they saw it, decided to play it for all it was worth. Anyhow, play it they did. They hired the W.J. Burns International Detective Agency to send an operative to investigate. The unnamed detective reported in a telegram to Screenland that he attended a meeting of the IPRS with about 150 others and was among those who inspected the cabinet Mrs. Tomson entered. He witnessed the emergence from the cabinet of “a white robed figure” who did not speak to him; another man on the platform asked the detective if he recognized the figure as Virginia Rappe. In his report the detective didn’t say one way or the other, but he said that was the only time Virginia’s name was mentioned. He said that Mrs. Tomson’s daughter Halma and Dr. Lawrence H. Rowell, president of the IPRS, told him of an earlier séance, attended by about 250, in which Virginia emerged from the cabinet onstage “in a bright blue light, wearing beautiful pure, white flowing robes [with] wonderful dark brown eyes and hair which hung over her shoulders” (per a related telegram to Screenland from Halma herself). She (Virginia) strode to the edge of the stage and addressed a newspaperwoman in the front row: “I am Virginia Rappe and must say that Roscoe Arbuckle is absolutely innocent of causing my death,” whereupon she “returned to the cabinet and faded away.”

Notwithstanding all the references to Mrs. Tomson’s “cabinet”, daughter Halma called it an “enclosure”, and described what sounds more like a kiosk than a cabinet: “…made of two sides and a top of one thickness of half inch wood securely fastened together and absolutely void of any traps or trickery. It is six feet high, about four and a half feet deep and four feet wide. The front is closed with one thickness of gray French velour drapery in which nothing could be concealed, with an opening in the center where the apparitions appear.” Halma then provided the names and (astonishingly, to 21st century readers) addresses of 11 men and women (“eye and ear witnesses”) whom she said comprised “the committee” — whether the committee of women who privately examined the nude Mrs. Tomson, or of men who examined the cabinet/enclosure, or both, or neither, is unclear.

Maybe I’ve seen The Front Page once too often, but I can’t help imagining gales of laughter echoing through the offices of Screenland Magazine as this article was passed around before going off to the printer — this, mind you, while Virginia Rappe was barely cold in her grave and Roscoe Arbuckle’s career and character were being assassinated in a San Francisco courtroom.

How far did the editors take it? Did they bother contacting any of those committee members? Mrs. J.K. Moorehead of 632 Maryland St., Gary, IN? Mrs. Jane Brooks in Room 1244 of Chicago’s Morrison Hotel? Mrs. Edna Bacon of Blackwell, OK? Surely not; communication was slower and more expensive in 1921. But if any Cinedrome readers can make out the list in the article that opens this post, and if you care to comb the 1920 US Census, knock yourselves out.

How far did the editors take it? Did they bother contacting any of those committee members? Mrs. J.K. Moorehead of 632 Maryland St., Gary, IN? Mrs. Jane Brooks in Room 1244 of Chicago’s Morrison Hotel? Mrs. Edna Bacon of Blackwell, OK? Surely not; communication was slower and more expensive in 1921. But if any Cinedrome readers can make out the list in the article that opens this post, and if you care to comb the 1920 US Census, knock yourselves out.

I didn’t bother with that, but I did do a little poking around, beginning with the International Psychical Research Society. No luck, though I found several similarly-named organizations, especially in Great Britain, where the vogue for spiritualism, always pretty strong, burgeoned in the years right after World War I. But of the IPRS itself I could find no trace.

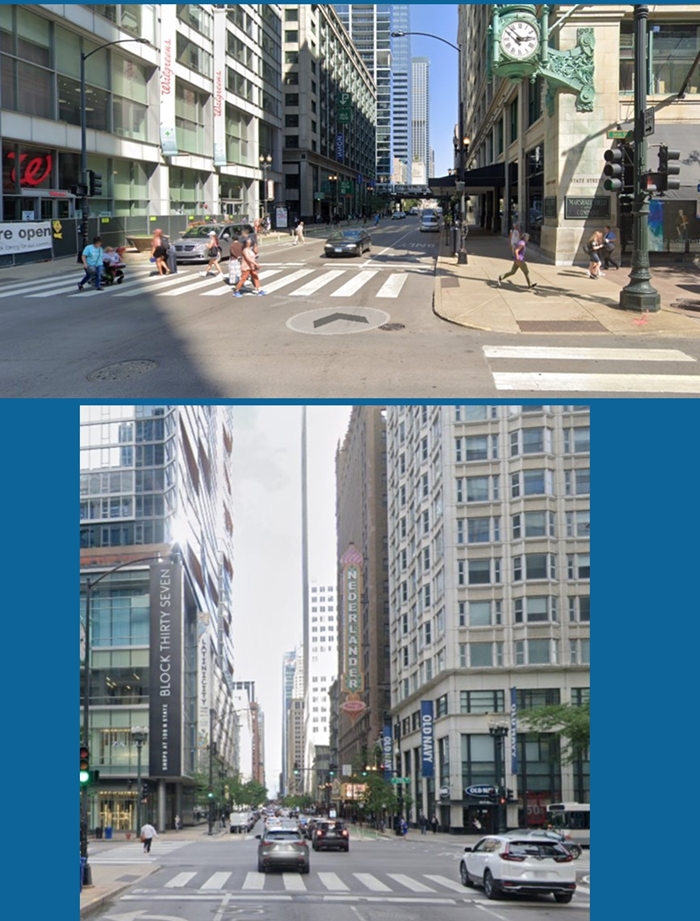

It was a different story, however, with the IPRS’s address at State and Randolph Streets in Chicago. That was a major intersection in downtown Chicago in 1921, and it still is today. Here are two recent views from the middle of State St. looking down Randolph to the east (above) and west (below). The only corner of the intersection that is reasonably intact from 1921 is the southeast corner, the site of Marshall Field’s, Chicago’s legendary upscale department store. Marshall Field’s is no more, having been bought out by Macy’s in 2005, but the Marshall Field — er, Macy’s — building at State and Randolph is a designated Chicago Landmark, as well as being on the National Register of Historic Places. So the building, with its “Marshall Field and Company” bronze plate and iconic green clock, is intact from the day construction was finished in 1906. A time traveler from 1921 would recognize it on sight.

The other corners, probably not so much. Presumably the IPRS was housed in one of those; if the Society had had an office in the Marshall Field Building, their letterhead would surely have said so. Personally, I vote for the northwest (Old Navy) corner, if only for the proximity of the Nederlander Theatre a few doors down; I like to fancy that the theater was rented by the Society to stage their “experiments”. Of course, it wasn’t the Nederlander then; it wasn’t even the same building, though there’s been a theater on the site since 1903. From 1905 to 1924 it was the Colonial, then it was torn down and replaced with the Oriental, renamed the Nederlander in 2019. Before 1905 it had borne the most notorious name of all American theaters: Iroquois. The Iroquois Theatre opened on November 23, 1903; one month and one week later, at a holiday matinee packed with some 2,200 patrons (many of them women and children), errant sparks from an arc light ignited a blaze that mushroomed within minutes into the deadliest single-building fire in American history, with at least 602 dead from burns, smoke inhalation, and trampling in the panic to escape. There’s a morbid fascination to the idea of Elizabeth Allen Tomson communing with spirits of the departed in such a building, but it probably didn’t happen there — if it had, there could have been over 600 ghosts elbowing Virginia Rappe aside, vying for Mrs. Tomson’s attention.

As for the personalities identified by name in the Screenland article, as I said, I didn’t bother scouring the 1920 Census for traces of that 11-person “committee”. Likewise, with Roy Jefferson, secretary of the IPRS, Googling such an ordinary name struck me as a futile exercise. But with Elizabeth Allen Tomson, much to my surprise, I hit paydirt.

It turns out Mrs. Tomson and her family had been running this spirit cabinet game for at least a year. Thanks to a Spanish-language blog, SurvivalAfterDeath | Psychic Sciences, I even found this 1920 photo of Mrs. Tomson in action. Well, more or less in action; the picture is obviously posed for the camera, with none of the lighting effects described in the Screenland article. But at least it gives us faces to go with the names. Mrs. Tomson is seated at center, beaming at someone draped in white, standing in for the ectoplasmic apparitions that were no doubt enacted by Mrs. Tomson herself in performance. At right is her husband/manager/spokesman Clarence, and at left is their daughter Halma. (I wonder if Halma herself didn’t contrive to stand in for Virginia; she seems a lot more age-appropriate.)

It turns out Mrs. Tomson and her family had been running this spirit cabinet game for at least a year. Thanks to a Spanish-language blog, SurvivalAfterDeath | Psychic Sciences, I even found this 1920 photo of Mrs. Tomson in action. Well, more or less in action; the picture is obviously posed for the camera, with none of the lighting effects described in the Screenland article. But at least it gives us faces to go with the names. Mrs. Tomson is seated at center, beaming at someone draped in white, standing in for the ectoplasmic apparitions that were no doubt enacted by Mrs. Tomson herself in performance. At right is her husband/manager/spokesman Clarence, and at left is their daughter Halma. (I wonder if Halma herself didn’t contrive to stand in for Virginia; she seems a lot more age-appropriate.)

The Tomsons popped up once more in the historical record — at least in that portion of it that I was able to uncover. This story comes to us through the efforts of Sarah Quick of the Brooklyn Public Library’s Web site.

In 1922, the magazine Scientific American offered a $2,500 prize to anyone who could offer proof of spiritual or psychic phenomena, and the Tomson family decided to go for it. Almost exactly two years after Elizabeth Allen Tomson channeled the ghost of Virginia Rappe to exonerate Roscoe Arbuckle, they descended on New York with all their paraphernalia and presented a series of séances in homes around the city. This caught the attention of another medium, one Lillian C. Briton of the Church of Spiritual Illumination in Brooklyn. Exactly how sincere a medium Miss Briton was, Sarah Quick doesn’t say, but she was convinced Mrs. Tomson was a fraud, and was determined to save Scientific American the trouble of debunking her. So Miss Briton invited Mrs. Tomson to perform a séance at her church, before an audience which (unbeknownst to the Tomsons) was laced with Miss Briton’s own “ghost breakers”, who would turn on the lights and grab the Tomsons at Briton’s arranged signal. All was going as planned, with the usual dim blue light and soft music (the violin solo replaced by a phonograph playing “Rock of Ages”), when Dick Gallagher, one of Briton’s agents, jumped the gun. Invited to peek in the cabinet to see, Gallagher was standing with Halma Tomson holding his hands (ostensibly to strengthen the psychic bond, but probably just to keep his hands from grabbing anything they shouldn’t). He found himself confronted with what purported to be his deceased grandmother, who leaned out of the cabinet and tried to embrace him. With his hands pinioned by Halma, and moved either by panic or calculation, Gallagher did the only thing he could: He leaned forward and bit the ghost as hard as he could: “I bit my Grandmother and it was Mrs. Tomson,” he recalled. Mrs. Tomson burst out the back of the cabinet in her bathrobe and ran upstairs, where she fainted. Gallagher had bitten the “ghost” so hard that the silken cloud-like cloth she wore became lodged in his teeth. The next day the Tomsons slunk back to Chicago, with Clarence Tomson blustering about severed spiritual connections and unworthy motives, and demanding the return of their silk cloth. In the end, Scientific American monitored over 100 séances but never had to pay up. The Tomsons never even got a hearing.

Thus do Elizabeth, Clarence, and Halma Tomson disappear from history, at least as far as I could ascertain; read Sarah Quick’s post at the link above for the full hilarious details of their Brooklyn Waterloo. But let’s try not to judge them too harshly. I like the approach of the Screenland staff: However cynically they may have regarded the assertions of the International Psychical Research Society, they were gracious enough to keep a straight face in print, and they gave the Society a fair hearing. And too, let’s give credit where it’s due: Whether or not Mrs. Tomson had the endorsement of Virginia Rappe’s Testimony from Beyond, she was right. Roscoe Arbuckle was railroaded, guilty of nothing worse than partying hearty with illegal liquor. We know that now, and Elizabeth Allen Tomson said so before most people.