The Mark of Kane

As a rule, Cinedrome doesn’t concern itself with the contemporary movie scene, or with any movie made after, say, 1964 or so (that being the year to which I more or less arbitrarily date the end of Hollywood’s Golden Age). But rules are for breaking, after all, and I last broke that one in February 2019, when I wrote that Mary Poppins Returns was manifestly the best and most enduring movie of 2018 (when I bought the Blu-ray in early ’19, I told the twenty-something Target clerk who rang it up, “It’s the only movie from last year that your great-grandchildren will know.”) I used that observation to segue into a discussion of the long shadow of Walt Disney. My original plan was to follow up with a second post about the contentious relationship between author P.L. Travers and Disney’s Bill Walsh, Don Da Gradi and the Sherman Brothers in crafting the script, with possibly a sidebar discussion of 2013’s bucket of enjoyable hogwash Saving Mr. Banks, which purported to tell the same story. But in reading up on it, I found the querulous, intransigent Ms. Travers such churlish and unpleasant company that I dropped the idea early on, and that follow-up post (“Mary Poppins: Enter the Dragon”) never materialized.

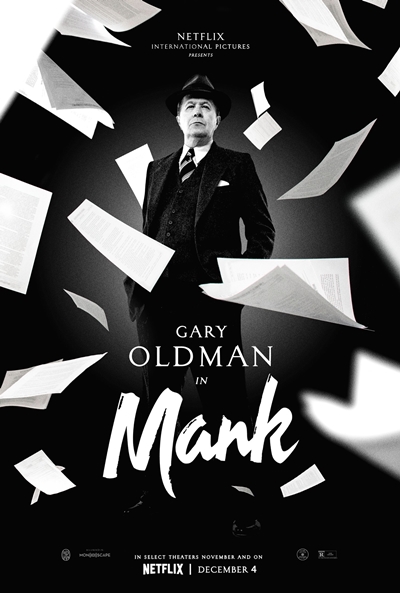

Well, that was then, this is now, and I’m breaking that rule again to discuss another contemporary movie and another long shadow. The movie is Mank, directed by David Fincher from a script by his father Jack, and the shadow belongs to Citizen Kane (1941). The younger Fincher appears to have undertaken Mank as a tribute to his father, who died in 2003 (the movie is dedicated to his memory). Besides that, it fits into the intermittent vogue for making movies about the making of movies — that is, about the making of specific movies. It’s a sub-genre that dates back at least as far as 1980’s TV movie The Scarlett O’Hara War, in which 55-year-old Tony Curtis played the 35-year-old David O. Selznick beating the bushes to find a leading lady for Gone With the Wind. The vogue has cropped up from time to time ever since; examples include the aforementioned Saving Mr. Banks and 2012’s Hitchcock, about the making of Psycho. Even Citizen Kane‘s production has been done before, in RKO 281 (1999), with Liev Schreiber as Orson Welles and James Cromwell as William Randolph Hearst.

Well, that was then, this is now, and I’m breaking that rule again to discuss another contemporary movie and another long shadow. The movie is Mank, directed by David Fincher from a script by his father Jack, and the shadow belongs to Citizen Kane (1941). The younger Fincher appears to have undertaken Mank as a tribute to his father, who died in 2003 (the movie is dedicated to his memory). Besides that, it fits into the intermittent vogue for making movies about the making of movies — that is, about the making of specific movies. It’s a sub-genre that dates back at least as far as 1980’s TV movie The Scarlett O’Hara War, in which 55-year-old Tony Curtis played the 35-year-old David O. Selznick beating the bushes to find a leading lady for Gone With the Wind. The vogue has cropped up from time to time ever since; examples include the aforementioned Saving Mr. Banks and 2012’s Hitchcock, about the making of Psycho. Even Citizen Kane‘s production has been done before, in RKO 281 (1999), with Liev Schreiber as Orson Welles and James Cromwell as William Randolph Hearst.

Mank covers ground similar to RKO 281, but concentrating not on Welles (played by Tom Burke as a drive-by cameo) but on co-writer Herman J. Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman). In the spring of 1940, after hashing out with Welles a rough outline of what would become Citizen Kane, Mankiewicz was dispatched to a distraction-free exile in Victorville, in the middle of California’s Mojave Desert, to crank out a first draft. He was encased in a half-body cast after thrice-breaking his leg in September ’39 in an auto accident en route to New York. He had just been fired from MGM and was headed east to beg work from friends, having burned too many bridges in Hollywood; his convalescence put the kibosh on that, but it led to the job with Welles.

Accompanying Mankiewicz to Victorville was a German nurse (named “Fräulein Frieda” in Mank and played by Monika Grossman); an English secretary, Rita Alexander (Lily Collins), whose last name would be used for Charles Foster Kane’s second wife; and Welles’s former producer John Houseman (Sam Troughton), who had had a violent falling-out with the Boy Genius but was coaxed back for this assignment at Mankiewicz’s request. Mank covers the twelve weeks the group spent writing, editing, and (in Mankiewicz’s case) recuperating in Victorville, with flashbacks to Herman’s feckless, self-destructive career in Hollywood to that time.

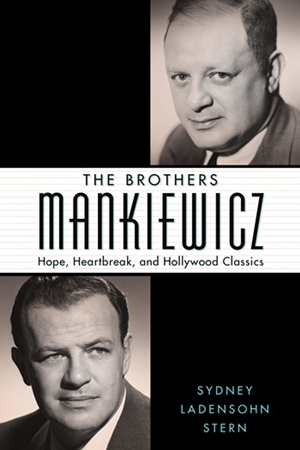

As luck would have it, the theatrical-and-streaming release of Mank followed close on the heels of my reading Sydney Ladensohn Stern’s definitive dual biography The Brothers Mankiewicz: Hope, Heartbreak, and Hollywood Classics. Ms. Stern’s subject, of course, is not only Herman J. Mankiewicz but his kid brother Joseph L., their literary ambitions and cinematic achievements. Both spent their lives hungry for the approval of their college professor father, who always seemed to feel his sons were wasting their abilities by working in movies. She makes a convincing case that Herman’s accomplishments arguably surpassed those of “Pop”, and that Joe’s undeniably surpassed them both, yet neither quite managed (if only in their own eyes) to live up to Pop’s expectations.

The Brothers Mankiewicz was published just over a year ago, much too late for Ms. Stern’s research and insights to have benefited Fincher père when he wrote Mank, or Fincher fils when he filmed it, but in plenty of time to pique our interest in their movie — at least it piqued mine — and to let us compare it with the historical record.

The impetus for this post was an email from my friend Jean in Spokane, Washington, who asked me what I thought of it. She said she had a “fairly middle of the road reaction to it overall”; she “did find it a bit long” but was fascinated by “the way it presents the characters — the Mankiewiczes, Mayer, Thalberg, Hearst et al.” and was particularly impressed by Amanda Seyfried’s performance as Marion Davies. She also spoke well of Tom Burke as Welles. I told her that no, I hadn’t seen Mank yet, but I was looking forward to it, especially now that I’d read Sydney Stern’s book — twice: once to myself, then again to my uncle.

Speaking of people playing Orson Welles in movies [I wrote her], have you by any chance seen Richard Linklater’s Me and Orson Welles (2008)? I urge you to give it a look; it’s a modest masterpiece. It’s based on a 2003 novel by Robert Kaplow; Zac Efron plays this high school kid in 1937 who stumbles into a sort of internship with the Mercury Theatre and works on Orson Welles’s modern-dress Fascist-themed production of Julius Caesar. Welles is played by one Christian McKay, and he’s absolutely uncanny. Should have won an Academy Award, but like most people who deserve Oscars, he wasn’t even nominated; besides, it was 2008, and that was the year they decided to give it to Heath Ledger for being dead. The movie is a brilliant portrait of Welles at a time when his career was still rocketing upward, with the sky seemingly the limit, and Welles himself was like an unstoppable force of nature, by turns inspiring and insufferable, but always Herculean and awe-inspiring. Also, it’s probably as close as we’ll ever get to feeling the impact of that Caesar (scenes from which were, I understand, painstakingly researched and recreated). It’s also brilliantly cast; McKay is actually just first among equals. This is all the more impressive in that there are only three major characters who are fictitious, played by Efron, Claire Danes and Zoe Kazan. Just about everybody else in the cast is not only historical, but familiar from countless movies – Joseph Cotten, Martin Gabel, John Houseman, John Hoyt, Norman Lloyd, George Coulouris, Les Tremayne. All of them perfect, especially a fellow named James Tupper as Joseph Cotten – I mean, how would you go about even looking for the ideal Joseph Cotten? So kudos to Lucy Bevan, the casting director (casting directors are often unsung heroes of movies, and never more so than here). (And by the way, in case you didn’t notice, dear old Norman Lloyd is still with us, bless his heart, having turned 106 exactly one month ago; continued long life to him, say I.) (UPDATE 6/20/21: Norman Lloyd passed away on May 11, 2021 at age 106.)

And so it was, with the memory of Me and Orson Welles fairly fresh in my mind, that I sat down a couple of nights later to watch Mank on Netflix. What follows it what I wrote to Jean a few days after that.

* * *

Hi Jean —

I watched Mank the other night, and I’ve spent the last couple of days mulling over what to tell you about it, and I finally decided what the hell, I might as well cut to the chase.

I detested it. I found it to be a pompous, overstuffed, bloviating gasbag of a movie, a comically dumb-ass parade of falsehoods great and small. I’ll start with the great ones – which, paradoxically, are the least important. By “great” I mean the movie as a chronicle of the writing of Citizen Kane. Bullcrap from first frame to last. I hardly know where to begin with its tin-eared idiocies, but a few more-or-less random thoughts:

Marion Davies went to her grave insisting that she never saw Citizen Kane, and while I’m not sure I believe that, it was her story and she stuck to it to the end. In any case, the idea that she would have driven out to Victorville to sit on the porch critiquing the fine points of Mankiewicz’s script before shooting even started is just plain stupid.

Marion Davies went to her grave insisting that she never saw Citizen Kane, and while I’m not sure I believe that, it was her story and she stuck to it to the end. In any case, the idea that she would have driven out to Victorville to sit on the porch critiquing the fine points of Mankiewicz’s script before shooting even started is just plain stupid.

Also, somewhere along the line the movie goes off onto a completely irrelevant tangent about Upton Sinclair’s 1934 campaign for governor of California, and the fake newsreels MGM made to undermine him. (This may be why you found it “a bit long”; cutting this wild goose chase could have saved half an hour to 45 minutes.) Herman Mankiewicz had nothing to do with any of that, and none of that had anything to do with writing Citizen Kane. I don’t know why it was even there (honestly, by that time my attention had already begun to wander), but it appeared to me that the movie was suggesting that Mankiewicz somehow undertook Kane as revenge against Hearst for spearheading the torpedoing of Sinclair’s campaign, and for helping drive Mankiewicz’s pal Shelly Metcalf to suicide out of shame over his part in it. Bollocks, bollocks, and bollocks. To begin with, “Shelly Metcalf” never existed, and nobody in Hollywood cared that Upton Sinclair lost the election or that MGM’s “newsreels” had anything to do with it. Certainly nobody killed themselves out of guilt over it — that’s a daydream of 21st century leftists.

At one point Mankiewicz tells Marion Davies, in one of their soulful moonlight chats on the grounds at San Simeon (itself a silly invention), that L.B. Mayer loathes Sinclair because Sinclair wrote that he “took a bribe to look the other way so a rival could buy MGM.” Another crock. The movie doesn’t say who this “rival” was, but it may be a reference to William Fox, who in the late 1920s did indeed embark on a project to buy every studio in Hollywood, intending to monopolize the business. (Adolph Zukor at Paramount had tried something similar in the late 1910s, and Thomas Edison before him. Monopoly-building has always been a tempting pastime in the movie business, and such efforts continue to this day.) Fox started by aiming big and, yes, he did try to buy MGM. He came pretty close, too — but far from looking the other way, Mayer (and Thalberg) fought doggedly against the deal. Almost to no avail; Fox came very near to pulling it off. Then, in the summer of 1929, Fox was in a horrible automobile accident that damn near killed him. He was months recuperating, and just as he was getting up and around again, the stock market crashed, taking all his credit with it. Fox was overextended, creditors pounced, and when the dust cleared he was ruined. By late 1930 he was out of the movie business forever (he lived on until 1952). He didn’t buy MGM – or rather, he did, in a way, but when the chips were down he didn’t have the cash to close the deal, and Mayer’s job at the studio was saved. I don’t know what Upton Sinclair may have written (he did write a book, Upton Sinclair Presents William Fox, published in 1933), and Mayer, a conservative Republican, may well have loathed Sinclair. But Sinclair wrote nothing about any bribe because there wasn’t one.

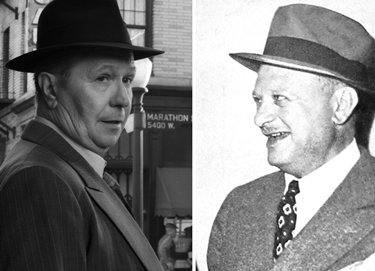

There’s hardly a detail too minor for the movie to go out of its way to get wrong. Herman Mankiewicz had a mustache in 1940. Marion Davies was sweet and well-loved, but she drank too much and, having retired from the screen in 1937, she was puffy and tending to overweight by 1939; also, she stuttered. As for Rita Alexander, no Englishwoman then, or Englishman either, would have used the word “shitty” in mixed company, even if they did think aircraft carriers were “a shitty idea” (which nobody did). That word was a pure Americanism – and for that matter, even in America few women would have said it in those days. The road accident that broke Mankiewicz’s leg happened not because a letter fluttered out of his convertible with the top down, but because Tommy Phipps, who was driving, lost control of the car in the rain on Route 66. The Mankiewicz brothers never called each other “Hermie” and “Joey”, and nobody on Planet Earth was dumb enough to call William Randolph Hearst “Willie”, even behind his back in a soundproof room.

There’s hardly a detail too minor for the movie to go out of its way to get wrong. Herman Mankiewicz had a mustache in 1940. Marion Davies was sweet and well-loved, but she drank too much and, having retired from the screen in 1937, she was puffy and tending to overweight by 1939; also, she stuttered. As for Rita Alexander, no Englishwoman then, or Englishman either, would have used the word “shitty” in mixed company, even if they did think aircraft carriers were “a shitty idea” (which nobody did). That word was a pure Americanism – and for that matter, even in America few women would have said it in those days. The road accident that broke Mankiewicz’s leg happened not because a letter fluttered out of his convertible with the top down, but because Tommy Phipps, who was driving, lost control of the car in the rain on Route 66. The Mankiewicz brothers never called each other “Hermie” and “Joey”, and nobody on Planet Earth was dumb enough to call William Randolph Hearst “Willie”, even behind his back in a soundproof room.

But honestly, none of that is really important; in fact, it’s all beside the point. I mean, if you want to know about the gunfight at the O.K. Corral, you don’t watch John Sturges’s 1957 movie, or even John Ford’s My Darling Clementine; nor do you go to The Adventures of Robin Hood for insights about Medieval England in the reign of Richard I (or for that matter, to Shakespeare about Richard III). You certainly don’t sit through Lawrence of Arabia, your butt going permanently numb, if you want to know anything about T.E. Lawrence. So the fact that Mank falsifies the writing of Citizen Kane and the career of Herman J. Mankiewicz beyond any semblance of the actual events, is not what matters. The salient fact about Mank is simply that it’s a lousy movie.

I can’t really fault the actors, except that the roles they’re shoved into are unplayable and none of them seems to have complained about it. At a minimum, they do struggle bravely with dialogue that positively bristles with name-dropping howlers:

“Mark my words, The Wizard of Oz will sink that studio.”

“Well, you know most everyone here. Mr. Kaufman…” “‘George’ is fine, kid.” “…Mr. Perelman…” “Do you prefer Sidney or S.J.?”

“Aimee Semple McPherson says you’re a godless commie, Upton!”

“We all want to welcome the Thalbergs back from Irving’s long convalescence in Europe…”

“L.B., this is my brother Joe.” “Nice to meet you, Joseph, I’m Louis Mayer.” (As if Mayer would find it necessary to introduce himself to someone in his own office!)

“You all know Jo von Sternberg…”

“I love Lowell Thomas’s voice. I sat across from him at the Brown Derby once.”

“How is Marie Antoinette coming along?” “Norma is a nervous wreck.”

“That’s Herman Mankiewicz. He wrote one of our Lon Chaneys.”

“I know you, we met at John Gilbert’s birthday party; you’re Herman Mankiewicz…You fractured Wally Beery’s wrist Indian wrestling.”

There’s hardly a minute without such low-camp groaners. I’d love to go on, but you get the idea; the script is a chortler’s paradise.

The look of the movie is flat and murky. Not “evocative” or “atmospheric”, just dark and indistinct. It was shot in something called “Hi-Dynamic Range”, whatever the hell that is. Faces, even architectural details, are lost in shadows or merge into background darkness. The cinematography, credited to someone named Erik Messerschmidt, is perfectly atrocious. It’s obvious Messerschmidt didn’t light the film for black and white, he lit it for color and shot it that way, then just leached the color out, as if that’s the same thing. You light a subject differently for black and white than you do for color, a fact that they used to teach you in the first ten minutes of Photography 101. Either Mr. Messerschmidt cut class that day or he’s merely incompetent (that’s my vote). Either way, he’s in well over his head here, and I intend to remember that name.

Late in the movie, I think at the climax (such as it was), there was a long scene in the “Refectory” at San Simeon (although in Messerschmidt’s hands it just looked like a rather well-furnished cave). The scene seemed to be terribly important; anyhow, it had Gary Oldman going tooth-and-nail for his second Oscar. But by that time the movie had completely lost me and I was no longer even pretending to pay attention; I just sat there rolling my eyes and making that wrist-rotating gesture that is the universal signal for let’s-wind-this-thing-up-already. (I couldn’t help remembering something Pauline Kael wrote in one of her reviews: “Sitting in the darkened theater, I kept listening for snorts, but every time I heard one I could feel the breath on my hands.”) Somewhere in this seemingly-terribly-important scene, Mankiewicz puked and made his famous wisecrack about the white wine coming up with the fish (which actually happened at the home of Arthur Hornblow Jr.), but that’s really all I remember. I was just marking time, waiting for this ridiculous, fraudulent movie to be over. And then…finally…it was.

Late in the movie, I think at the climax (such as it was), there was a long scene in the “Refectory” at San Simeon (although in Messerschmidt’s hands it just looked like a rather well-furnished cave). The scene seemed to be terribly important; anyhow, it had Gary Oldman going tooth-and-nail for his second Oscar. But by that time the movie had completely lost me and I was no longer even pretending to pay attention; I just sat there rolling my eyes and making that wrist-rotating gesture that is the universal signal for let’s-wind-this-thing-up-already. (I couldn’t help remembering something Pauline Kael wrote in one of her reviews: “Sitting in the darkened theater, I kept listening for snorts, but every time I heard one I could feel the breath on my hands.”) Somewhere in this seemingly-terribly-important scene, Mankiewicz puked and made his famous wisecrack about the white wine coming up with the fish (which actually happened at the home of Arthur Hornblow Jr.), but that’s really all I remember. I was just marking time, waiting for this ridiculous, fraudulent movie to be over. And then…finally…it was.

So for what it’s worth, that’s my reaction to Mank, a silly and terrible movie where not a scene, not a minute, not a second, not a frame has the ring of truth – plus it’s ugly to look at, and it’s more trouble trying to peer through the stygian gloom than it’s worth. It’s 131 minutes I’ll never get back, but on the whole I might well have frittered the time away on something almost as useless, so no great harm done. Still, having gotten it out of the way, I now dismiss it from my mind forever, and I intend never to give it another moment’s thought.

On the other hand, I can’t wait to watch Me and Orson Welles again. Now that’s how it’s done.

All for now; write when you can.

Jim