Cary-ing On

At Cinevent 50 in Columbus, Ohio in 2018, there was a moderated Saturday-afternoon discussion between historians Leonard Maltin and Scott Eyman. At one point, Leonard said of Scott:

At Cinevent 50 in Columbus, Ohio in 2018, there was a moderated Saturday-afternoon discussion between historians Leonard Maltin and Scott Eyman. At one point, Leonard said of Scott:

“…Scott’s book on John Wayne is the best book on John Wayne, just as his book on Cecil B. DeMille is the definitive book on Cecil B. DeMille. I’m compulsive, but I’ve been tempted to actually discard some of my other books because they’re taking up shelf space…I’m too anal, I can’t get rid of the other books, but if I could tame my instincts I would just say, ‘These are useless now ’cause Scott’s done the ultimate job.”‘

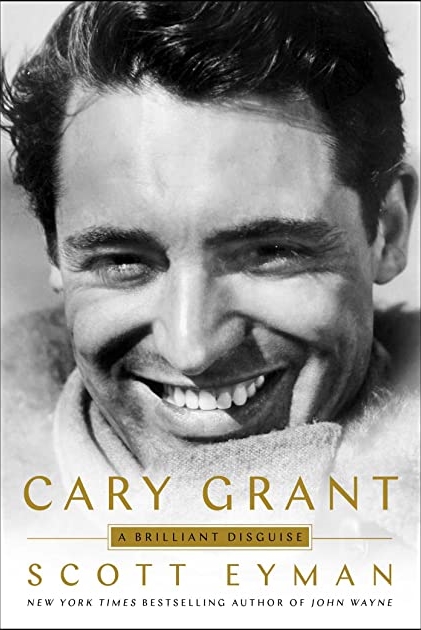

Well, if any of you out there happen to have a bookshelf groaning under the weight of books about Cary Grant (Amazon and Alibris list no fewer than twenty, not counting first-hand memoirs by his daughter Jennifer and her mother Dyan Cannon), and if you’re any less obsessive than Leonard Maltin, you can now free up some of that space, because Scott Eyman has done it again. Cary Grant: A Brilliant Disguise is surely — like Scott’s biographies of John Wayne, John Ford, Louis B. Mayer, Mary Pickford et al. — the next best thing to having known the subject personally.

Oddly enough, I thought of Cary Grant while reading one of Scott’s earlier books, John Wayne: The Life and Legend (2014). At the time I had no idea Scott would be doing a bio of Grant (and for all I know, neither did he); what made me connect the two was their similarity in thinking of themselves as distinct from their screen personae. Wayne never thought of himself as “John Wayne”; he was, essentially, Marion “Duke” Morrison, doing business as John Wayne. He never even changed his name legally — his death certificate reads “Marion Morrison (John Wayne)”. As Scott put it, John Wayne was to Duke Morrison as the Little Tramp was to Charles Spencer Chaplin, “a character that overlapped his own personality, but not to the point of subsuming it.”

Likewise, Cary Grant always — or at least for much of his career — thought of himself as Archibald Alexander “Archie” Leach of Bristol, UK. But there was a difference. For one thing, Grant did change his name legally, in 1942 (significantly, on the same day he became an American citizen). Despite that, however, he appears never to have seen the “personality overlap” that Duke Morrison had with John Wayne; “Archie Leach” and “Cary Grant” were two separate personalities, never the twain to meet — hence Scott’s subtitle, A Brilliant Disguise.

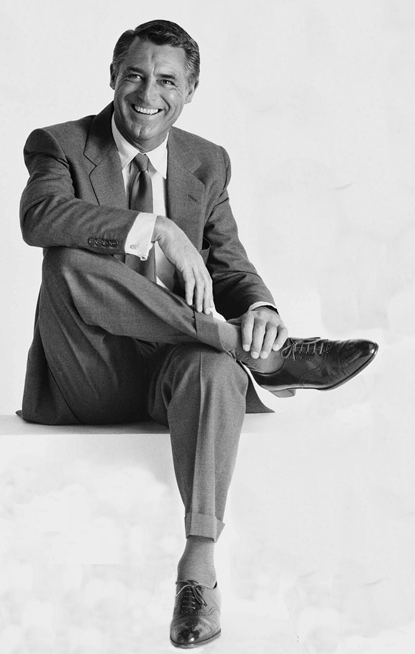

In writing about Scott’s John Wayne biography, I quoted Grant: “Everybody wants to be Cary Grant. Even I want to be Cary Grant.” It’s one of Grant’s most famous quotes — so famous, in fact, that Scott doesn’t even feel the need to include it. But he does offer an anecdote that makes much the same point: In 1973, Grant attended the American Film Institute tribute to John Ford. He had forgotten his ticket, and he asked the lady at the reception desk for help. She asked his name, and when he told her she peered at him. “You don’t look like Cary Grant.” Grant smiled. “I know,” he said. “Nobody does.”

For Archie Leach, the Cary Grant persona was, in Scott’s apt phrase, a brilliant disguise — but it was also a precarious balancing act. Somehow, through some alchemical mix of talent, timing, ambition and luck, this music hall acrobat from Bristol crafted a personality unlike any other. The only child of a feckless alcoholic father and an emotionally unstable mother (young Archie’s father committed her to a mental hospital and told the boy she had died; he didn’t learn the truth for over 20 years), Archie Leach managed to remodel himself into the epitome of urbane sophistication and the greatest romantic comedian in the history of the acting profession.

For Archie Leach, the Cary Grant persona was, in Scott’s apt phrase, a brilliant disguise — but it was also a precarious balancing act. Somehow, through some alchemical mix of talent, timing, ambition and luck, this music hall acrobat from Bristol crafted a personality unlike any other. The only child of a feckless alcoholic father and an emotionally unstable mother (young Archie’s father committed her to a mental hospital and told the boy she had died; he didn’t learn the truth for over 20 years), Archie Leach managed to remodel himself into the epitome of urbane sophistication and the greatest romantic comedian in the history of the acting profession.

Even his accent was unique. Where in the world did it come from? Not Bristol, where the local dialect is as distinctive as those for Scotland, Wales, or Cornwall. Cary Grant doesn’t sound British to a Brit, nor American to a Yank. Scott calls his accent “Mid-Atlantic”, but that doesn’t catch it either. The Mid-Atlantic accent is familiar to all actors, not “English” so much as “England-esque”. Think Vincent Price, Raymond Massey, or Brian Aherne. Cary Grant was different. No human being in history has ever talked the way he did — unless (like Rich Little, say, or Tony Curtis in Some Like It Hot) they were imitating Cary Grant.

You don’t look like Cary Grant. I know; nobody does…Everybody wants to be Cary Grant; even I want to be Cary Grant. That was the man’s dilemma: “Cary Grant” embodied a glamorous ideal that Archie Leach knew perfectly well was unattainable — or at least, if not exactly unattainable, it certainly wasn’t him. As a result, Cary/Archie spent pretty much his entire career grappling with an impostor complex, always looking over his shoulder, worried he’d be found out. Duke Morrison looked at John Wayne and saw himself; Archie Leach looked at Cary Grant and saw somebody else.

Cary Grant: A Brilliant Disguise paints a striking portrait of a man by turns charming and exasperating, immensely likeable when he wasn’t being an ambitious narcissist, or a penny-pinching fussbudget — and often, even when he was. (Scott illustrates the old saw that no man is a hero to his valet by quoting Dudley Walker, Grant’s actual valet in the 1940s: “…he was stingy as hell…too cheap to enjoy his own wealth.”)

As for the questions about Grant’s sexuality, and particularly those unkillable rumors about him and his 1930s housemate Randolph Scott, Scott Eyman tackles them head-on, while granting that evidence is thin on the ground and largely circumstantial. True, Grant and Randy Scott always spoke of each other with undeniable affection, and Scott E. doesn’t discount the possibility of, shall we say, youthful experimentation. But would a supposedly gay man bother to marry five times? A number of Grant’s wives and friends are heard from. Peter Bogdanovich once asked director Howard Hawks about the rumors, and Hawks snorted: “Every time I see him, he’s got a younger girl on his arm. No, that’s just ridiculous.” Grant’s first wife Virginia Cherrill once remarked on how great Cary was in bed, and called Randy Scott “a darling” when she and Grant double-dated with him and tobacco heiress Doris Duke: “Randolph Scott was no more gay than Cary was.” Third wife Betsy Drake said something similar, while fourth wife Dyan Cannon was downright blunt: “Why would I believe that Cary was homosexual when we were busy fucking?” Even so, she conceded: “He lived 43 years before he met me” — actually, it was 57 years — “I don’t know what he did [before that].” Grant himself (like Randolph Scott) tended to laugh off the rumors, though he had his limits: He blew his stack and sued when Chevy Chase called him “a homo…what a gal!” on Tom Snyder’s late-night talk show (it was settled out of court, and Chase apologized). Anyhow, Scott Eyman lays out the evidence, such as it is, and invites us to draw our own conclusions.

At Cinevent in 2018, Scott Eyman expressed hesitancy in approaching any forthcoming projects: “Now, I circle and circle, is this worth those years of my life I have remaining…?” At the time, he was midway through this book on Cary Grant. I trust that he still has many years remaining, and I hope he finds another subject soon. Personally, I vote for Lillian Gish. I’ve always wanted to meet her, and I’d like Scott Eyman to introduce us.