Ups and Downs of the Rollercoaster, Part 3

Lowell Thomas decided right off the bat — and Merian Cooper, when he came aboard, concurred — that the star of the first Cinerama picture would be Cinerama itself. “If Charlie Chaplin had offered to do Hamlet for us,” Thomas remembered, “I’d have turned him down. I didn’t want people judging Chaplin or rediscovering Shakespeare…The advent of something as new and important as Cinerama was a major event in the history of entertainment and I was determined to let nothing upstage it.” In other words, This Is Cinerama wasn’t a movie, it was a demonstration, just like Waller and Reeves’s screenings at their tennis court command post in Oyster Bay. The difference this time was that the presentation was more organized and formal, with tuxedo-clad personnel escorting the audience to their seats — and it was in Technicolor. (Mostly, anyhow; when opening night loomed and the feature was still a little short, Thomas and Cooper decided to splice in Waller’s black-and-white clip of the Long Island Choral Society singing Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus — it made a good demo of the sound system, with an invisible choir marching down the aisles of the theater before coming into view on the screen.) So in a sense, Cinerama was exactly where it was before the opening — only now the whole world was watching.

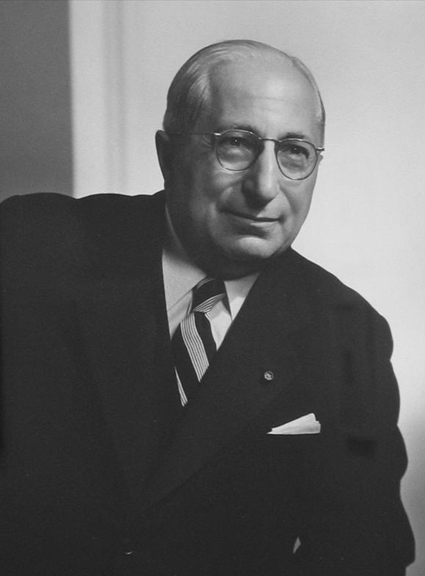

Lowell Thomas decided right off the bat — and Merian Cooper, when he came aboard, concurred — that the star of the first Cinerama picture would be Cinerama itself. “If Charlie Chaplin had offered to do Hamlet for us,” Thomas remembered, “I’d have turned him down. I didn’t want people judging Chaplin or rediscovering Shakespeare…The advent of something as new and important as Cinerama was a major event in the history of entertainment and I was determined to let nothing upstage it.” In other words, This Is Cinerama wasn’t a movie, it was a demonstration, just like Waller and Reeves’s screenings at their tennis court command post in Oyster Bay. The difference this time was that the presentation was more organized and formal, with tuxedo-clad personnel escorting the audience to their seats — and it was in Technicolor. (Mostly, anyhow; when opening night loomed and the feature was still a little short, Thomas and Cooper decided to splice in Waller’s black-and-white clip of the Long Island Choral Society singing Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus — it made a good demo of the sound system, with an invisible choir marching down the aisles of the theater before coming into view on the screen.) So in a sense, Cinerama was exactly where it was before the opening — only now the whole world was watching.  The first new development, barely three weeks after the premiere, was the appointment of Louis B. Mayer as chairman of the board of Cinerama Productions Corp. (with Lowell Thomas stepping down to vice-chairman). There was a certain irony in this; Mayer was one of the movie industry figures who trooped out to Long Island for those demonstrations, only to take a pass on investing. Back then, Mayer had been probably the most powerful man in Hollywood, but this was now. In the interim there had been that ugly power struggle at MGM between Mayer and Dore Schary, ending in a humiliating palace coup that sent Mayer packing in July 1951. By October ’52, Mayer was restless in forced retirement, and Cinerama looked like his passport back into the business. For Cinerama it was a windfall in both money (Mayer’s personal investment reportedly amounted to over $1 million) and prestige: Mayer’s status as a pioneer and longtime chief of the Tiffany of Hollywood studios gave an aura of solidity to Cinerama, and his reputation for showbiz acumen was expected to reassure and attract investors. He brought along some possible material, too: Mayer personally held the screen rights to several properties. One of them, Blossom Time, a moldy Viennese operetta of the sort Mayer had once so lovingly dusted off for Nelson Eddy and Jeanette MacDonald, would never do. But others might work very nicely, like the Lerner and Loewe musical Paint Your Wagon and the Biblical epic Joseph and His Brethren.

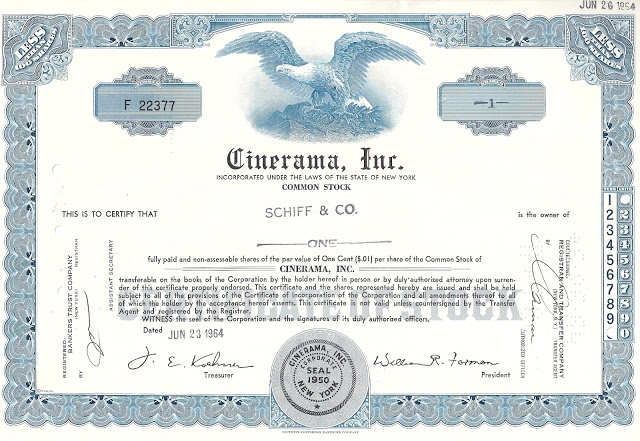

The first new development, barely three weeks after the premiere, was the appointment of Louis B. Mayer as chairman of the board of Cinerama Productions Corp. (with Lowell Thomas stepping down to vice-chairman). There was a certain irony in this; Mayer was one of the movie industry figures who trooped out to Long Island for those demonstrations, only to take a pass on investing. Back then, Mayer had been probably the most powerful man in Hollywood, but this was now. In the interim there had been that ugly power struggle at MGM between Mayer and Dore Schary, ending in a humiliating palace coup that sent Mayer packing in July 1951. By October ’52, Mayer was restless in forced retirement, and Cinerama looked like his passport back into the business. For Cinerama it was a windfall in both money (Mayer’s personal investment reportedly amounted to over $1 million) and prestige: Mayer’s status as a pioneer and longtime chief of the Tiffany of Hollywood studios gave an aura of solidity to Cinerama, and his reputation for showbiz acumen was expected to reassure and attract investors. He brought along some possible material, too: Mayer personally held the screen rights to several properties. One of them, Blossom Time, a moldy Viennese operetta of the sort Mayer had once so lovingly dusted off for Nelson Eddy and Jeanette MacDonald, would never do. But others might work very nicely, like the Lerner and Loewe musical Paint Your Wagon and the Biblical epic Joseph and His Brethren. There was a flurry of announcements in trade papers. Dudley Roberts, president of Cinerama Productions, said Cinerama would open theaters in 100 cities, to be supplied with six to eight full-length features a year. Merian Cooper, now head of production, promised that Cinerama would either buy or build its own studio in Hollywood. (Might Cooper have had his eye on RKO? The studio was then in the process of being run into the ground by Howard Hughes, and ripe for the picking. If so, it didn’t happen; when RKO finally sold it went first to General Tire and Rubber Co., then to Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, who renamed it Desilu.)

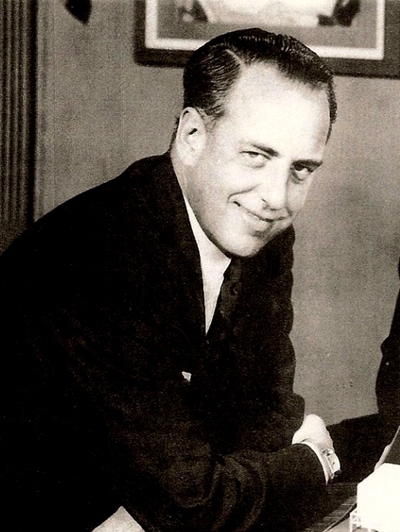

There was a flurry of announcements in trade papers. Dudley Roberts, president of Cinerama Productions, said Cinerama would open theaters in 100 cities, to be supplied with six to eight full-length features a year. Merian Cooper, now head of production, promised that Cinerama would either buy or build its own studio in Hollywood. (Might Cooper have had his eye on RKO? The studio was then in the process of being run into the ground by Howard Hughes, and ripe for the picking. If so, it didn’t happen; when RKO finally sold it went first to General Tire and Rubber Co., then to Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, who renamed it Desilu.) The first dramatic Cinerama picture, Cooper said, would begin shooting within two months with himself producing and directing, followed within a year by a second feature, probably directed by Cooper’s Argosy Films partner John Ford. (As it happened, Ford didn’t work in Cinerama until almost ten years later, and he wasn’t happy with it or well suited, contributing the shortest and weakest episode of How the West Was Won.)

An array of productions were considered, and some even announced. Paint Your Wagon. Tolstoy’s War and Peace. A remake of King Kong. Lawrence of Arabia (this would have been a much different picture from the one we eventually got; Lowell Thomas didn’t much care for David Lean’s 1962 take on his old friend). Paul Mantz climbed back in the cockpit of his converted B-25 and shot another 200,000 feet, at a cost of $500,000, without anybody knowing when or how it would be used.

Some of Mantz’s footage eventually wound up in Seven Wonders of the World (’56). But as for all those other ambitious plans, none of them ever came to pass.

Part of the reason was L.B. Mayer himself. Biographer Scott Eyman speculates that Mayer’s enthusiasm for Cinerama was never that great in the first place; he may have been clinging to the forlorn hope that his exile from MGM was only temporary, intending Cinerama as a base from which to stage a return to Culver City. Whatever his intentions, the battle with Dore Schary had left him, in Lowell Thomas’s words, “aging, tired [and] unable to make up his mind about anything.” (Eyman memorably quotes writer Gavin Lambert, who covered Mayer at the time, in almost the same words: “He was an aging, tired man in a dark suit, who looked like a businessman but was actually an exiled emperor.”) Mayer eventually left Cinerama, though sources vary on exactly when. Eyman dates Mayer’s departure to November 1954; Thomas Erffmeyer’s history implies (and an article in the Winter 1992 issue of The Perfect Vision says outright) that it may have been as early as May ’53. In any event, Cinerama Productions Corp. produced nothing under Mayer’s chairmanship, and frittered away much of its early momentum.

Great site, Jim. For the 60th anni, I've opened mine as well: thiswascinerama.com. I came into possession of most of Hazard Reeves' Cinerama and your comments about the lack of foresight conerning Fox' CinemaScope is right on. Of the 2000+ articles in his memorabilia from 1952 through 1959, there was only once single mention of something upcoming called "cinemascope." They simply weren't worried. A copy of the Reeves collection is in the Performing Arts Library at Lincoln Center, and it (long story) includes a few items not in mine. Relevant to this post…there's a ticket to the world premiere of "The Robe" personally signed by Skouras and addressed to Mr. and Mrs. Hazard Reeves.

Vince Young hosting thiswascinerama.com.