The Could-Have-Been-Greater Moment

The facts are messier and less clear-cut. For one thing, Unfaithfully Yours (1948) may have flopped at the box office, but Sturges’ craft was as strong as ever, and the picture can stand now beside The Lady Eve and Sullivan’s Travels without blushing. But that’s a subject for another post; more to our present point, let’s not read too much into The Great Moment‘s eventual release date — September 9, 1944, on the heels of the giddy peaks of The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek and Hail the Conquering Hero. That skews the chronology. In fact, Sturges began writing The Great Moment (under his own title, Triumph over Pain) in 1939, even before he became a director of his own scripts. And he shot it from April to June 1942, between The Palm Beach Story and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek. In other words, he started work on the picture while he was still on the rise, and shot and edited it (to his own satisfaction, if not Paramount’s) while he was at his absolute peak.

Actually, it gets even messier than that. I think I’d better back way up and start at the beginning.

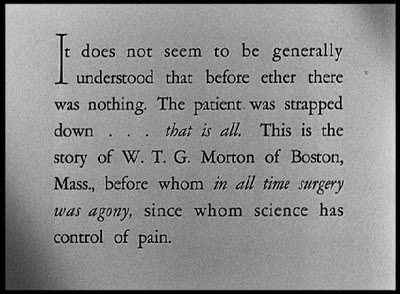

The Great Moment is one of two Sturges scripts to deal with a historical personage (the other was Diamond Jim [1935]). The subject here is William Thomas Green Morton (1819-68), a Boston dentist who in 1846 stumbled upon the use of ether as an anesthetic for the extraction of teeth. At first he had great success with his painless dentistry, disguising his simple discovery with the patent name Letheon. When he offered the use of Letheon in more serious surgery, he was forced to disclose its ingredients — or rather, sole ingredient. Almost immediately he was besieged with accusations that he had pirated the work of others, specifically fellow dentist Horace Wells and physician Charles T. Jackson, both of whom were personally acquainted with Morton, and Dr. Crawford W. Long of Georgia, who was not. Morton embarked upon an ill-advised lawsuit against the U.S. military for infringement of his Letheon patent, which only resulted in bad publicity for him; his patent was ultimately ruled invalid, and by 1850 the use of ether in surgery was virtually universal.

The Great Moment is one of two Sturges scripts to deal with a historical personage (the other was Diamond Jim [1935]). The subject here is William Thomas Green Morton (1819-68), a Boston dentist who in 1846 stumbled upon the use of ether as an anesthetic for the extraction of teeth. At first he had great success with his painless dentistry, disguising his simple discovery with the patent name Letheon. When he offered the use of Letheon in more serious surgery, he was forced to disclose its ingredients — or rather, sole ingredient. Almost immediately he was besieged with accusations that he had pirated the work of others, specifically fellow dentist Horace Wells and physician Charles T. Jackson, both of whom were personally acquainted with Morton, and Dr. Crawford W. Long of Georgia, who was not. Morton embarked upon an ill-advised lawsuit against the U.S. military for infringement of his Letheon patent, which only resulted in bad publicity for him; his patent was ultimately ruled invalid, and by 1850 the use of ether in surgery was virtually universal. What happened to Triumph over Pain once it passed through the Paramount gate is a little foggy, which could often be the case when a property bought on spec bounced around a studio full of producers and writers trying to wrestle it into a screen treatment and, eventually, a script. In his detailed introduction in Four More Screenplays by Preston Sturges, Brian Henderson (citing Sturges biographer James Curtis) says there was first an extended treatment (perhaps even a script) by Samuel Hoffenstein. Over at Turner Classic Movies, on the other hand, their notes on The Great Moment cite the Paramount Collection at the Motion Picture Academy Library in stating that the original 1939 script was written by Sturges, Irwin Shaw, W.L. “Les” River, Charles Brackett and Waldo Twitchell; the notes don’t say whether any of them worked in collaboration or simply took turns at the script as it moved from one writer to the next. Another Web site, giving no source for its information, further asserts that Ernst Laemmle (one of “Uncle” Carl Laemmle’s extended family, in fact his literal nephew) also had a hand in things somewhere. (UPDATE 1/7/24): That site, however, no longer exists; the text has gone the way of its unspecified sources.) In any case, all the sources agree that the original (possibly vague) idea was for Triumph over Pain to serve as a vehicle for Gary Cooper as Morton, to be directed by Henry Hathaway.

What happened to Triumph over Pain once it passed through the Paramount gate is a little foggy, which could often be the case when a property bought on spec bounced around a studio full of producers and writers trying to wrestle it into a screen treatment and, eventually, a script. In his detailed introduction in Four More Screenplays by Preston Sturges, Brian Henderson (citing Sturges biographer James Curtis) says there was first an extended treatment (perhaps even a script) by Samuel Hoffenstein. Over at Turner Classic Movies, on the other hand, their notes on The Great Moment cite the Paramount Collection at the Motion Picture Academy Library in stating that the original 1939 script was written by Sturges, Irwin Shaw, W.L. “Les” River, Charles Brackett and Waldo Twitchell; the notes don’t say whether any of them worked in collaboration or simply took turns at the script as it moved from one writer to the next. Another Web site, giving no source for its information, further asserts that Ernst Laemmle (one of “Uncle” Carl Laemmle’s extended family, in fact his literal nephew) also had a hand in things somewhere. (UPDATE 1/7/24): That site, however, no longer exists; the text has gone the way of its unspecified sources.) In any case, all the sources agree that the original (possibly vague) idea was for Triumph over Pain to serve as a vehicle for Gary Cooper as Morton, to be directed by Henry Hathaway.For the next couple of years, Preston Sturges was one of the busiest men on the Paramount lot. He eventually won an Oscar for his McGinty script, by which time he’d finished two more pictures — Christmas in July and The Lady Eve, both top-to-bottom rewrites of scripts he had written years earlier. Next came Sullivan’s Travels and The Palm Beach Story, brand new projects that he wrote, shot, and had ready for release each within six months of day one. For his next project, Henderson speculates that Sturges hoped to avoid the stress and pressure of beginning a whole new script from scratch. If that was the case, then he had only one unproduced script left in his files: Triumph over Pain.

In the meantime, something else had happened: William LeBaron (shown here with Mae West) left Paramount in late 1941, to be replaced as head of production by Buddy De Sylva (at right). Sturges had a relationship of mutual trust and respect with LeBaron, but with De Sylva it proved to be another matter, and in time it poisoned the well for Sturges. The story is that DeSylva resented the autonomy Sturges enjoyed over his pictures. Any newspaper or magazine writer can tell you tales of editors who just have to tinker with even the best and cleanest copy, if only to justify their own existence and remind the writer who’s really in charge; De Sylva may have been one of those. The fact that Sturges’ movies made money would be an incentive rather than a deterrent: stick your oar in and when the picture hits you can grab a share of the credit; if it flops, you can blame the writer/director and claim you did your best to fix it. Besides, it was a power thing.

In the meantime, something else had happened: William LeBaron (shown here with Mae West) left Paramount in late 1941, to be replaced as head of production by Buddy De Sylva (at right). Sturges had a relationship of mutual trust and respect with LeBaron, but with De Sylva it proved to be another matter, and in time it poisoned the well for Sturges. The story is that DeSylva resented the autonomy Sturges enjoyed over his pictures. Any newspaper or magazine writer can tell you tales of editors who just have to tinker with even the best and cleanest copy, if only to justify their own existence and remind the writer who’s really in charge; De Sylva may have been one of those. The fact that Sturges’ movies made money would be an incentive rather than a deterrent: stick your oar in and when the picture hits you can grab a share of the credit; if it flops, you can blame the writer/director and claim you did your best to fix it. Besides, it was a power thing. “Formerly” because it had already run into trouble, even before Sturges left Paramount, and the title was only the beginning. Even in the middle of shooting, with Joel McCrea playing Morton, De Sylva had begun referring to the picture as Great Without Glory, pointedly signaling that Sturges’ (and Rene Fulop-Miller’s) title wasn’t going to fly with the higher-ups. Sturges declined to take the hint and went over De Sylva’s head — which Brian Henderson calls a “tactical error” — to Paramount vice president Y. Frank Freeman. Freeman took it to the board, who considered “all title suggestions” (Henderson doesn’t say what the suggestions included, but other sources mention Immortal Secret and Morton the Magnficent) and settled on Great Without Glory. De Sylva 1, Sturges 0.

The fact is, according to Henderson, Sturges seems not to have fully appreciated that Paramount, and Buddy De Sylva in particular, had been lukewarm at best about the picture from the very beginning; they indulged Sturges, even on his first script back in 1939, because they wanted to continue tapping his talent for comedy. (The ultimate fate of The Great Moment lends force to the idea that the studio regarded Sturges as a maker of comedies only, and couldn’t think outside that box.) Henderson suggests, and it makes sense to me, that Sturges squandered political capital in his fight to retain Triumph over Pain as his title, capital that might have been better deployed defending the picture itself. As if to confirm De Sylva and his minions in their belief that he was being hardheaded and obstinate, Sturges also picked another pointless hill to die on.

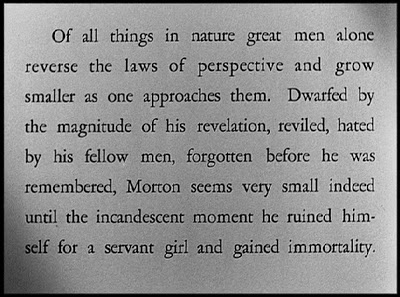

Sturges had written an acerbic introduction to Triumph over Pain, to be spoken in voice-over even before the opening credits. The passage stated — overstated — the picture’s central theme: that the greatest benefactors of mankind are often denounced and reviled in their own time. Fair enough, and W.T.G. Morton’s life, as recounted by Rene Fulop-Miller and Preston Sturges, was a fit text for preaching that sermon. But Sturges laid it on with a trowel:

One of the most charming characteristics of Homo Sapiens, the wise guy on your right, is the consistency with which he has stoned, crucified, burned at the stake, and otherwise rid himself of those who consecrated their lives to his further comfort and well-being so that all his strength and cunning might be preserved for the erection of ever larger monuments, memorial shafts, triumphal arches, pyramids and obelisks to the eternal glory of generals on horseback, tyrants, usurpers, dictators, politicians and other heroes who led him, usually from the rear, to dismemberment and death…

Well, subtlety never was part of Preston Sturges’ charm. But what the hell was he thinking? Never mind that, at the very moment he was committing these words to film, the United States was trudging through the bleakest days of World War II with no assurance of how it would turn out. Even aside from the morale-busting words — which would never have made it past the Office of War Information — there’s a sour tone to the intro that would put the most cheerful moviegoer into a foul and unreceptive mood. Sturges clung to this intro like a terrier to a rat; when De Sylva urged him to revise it, he doubled down: he changed “wise guy” to “talking gorilla.” By the time he finally agreed to this:

In fact, by that time, the picture had been whittled and rearranged into more or less the form that has come down to us. Previews on August 13 and 27, 1942 of the picture as Sturges made it (but with the title Great Without Glory) had gotten a mixed response, whereas Sturges’ previous pictures had garnered raves. De Sylva was more convinced than ever that major surgery was called for, and that’s what the picture got — probably between September and December ’42 while Sturges was busy shooting The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek.

Of the three pictures Sturges left behind at Paramount, only The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek was left as he made it; the other two got major overhauls from De Sylva and his editors. Miracle opened on January 19, 1944 and was an immediate smash hit. De Sylva’s cut of Hail the Conquering Hero was previewed the next month and was a disaster. Sturges offered to come back to Paramount without pay and re-edit and reshoot Hero and Great Without Glory “to everyone’s satisfaction.” He was allowed to doctor (and save) Hail the Conquering Hero — after all, that was a comedy, Sturges’ specialty. But on Great Without Glory (now The Great Moment) De Sylva put his foot down; that, he figured, was a waste of time and money.

Sturges tried the same tactical error that had failed before. He appealed to Y. Frank Freeman, saying there was still time “to save ‘The Great Moment’ from the mediocre and shameful career it is going to have in its present form and under its present title.” As it was, he said, the picture was “a guaranteed, gild-edged disaster”; a little time and money (“less than fifty thousand dollars”) could result in “a picture of dignity and merit.” But Paramount was indisposed to be accommodating; Freeman did not reply.

And so Preston Sturges’ Triumph over Pain remained The Great Moment as we know it today, shoved out into release in September ’44, nearly two-and-a-half years after shooting was complete. If it looks like the beginning of the end, a glaring “uh-oh”, to us now, it wasn’t quite that obvious to everyone at the time. Sturges still had his partisans, and some of them were better disposed to the picture than historians have been since. “[A]t least,” said Bosley Crowther in the New York Times, “Mr. Sturges has triumphed over stiffness in screen biography.” Likewise The New Yorker’s John Lardner: “…shows clearly that film biographies need not wear stuffing in their shirts.” In Variety, “Sten” called the story “compelling” and predicted it “should prove to be a good grosser.” But Sten was wrong. Other critics were less kind, and financially The Great Moment turned out every bit the disaster Sturges had glumly predicted.

I first planned this post with the idea of doing a compare-and-contrast between Sturges’ published script and the finished film. But that way lies madness; Buddy De Sylva and his crew made such a total hash of things that trying to follow The Great Moment with script in hand is like being backstage prompter for an actor who never learned his lines and keeps hopping around from scene to scene at random.

In fashioning a screenplay from Triumph over Pain, Sturges’ original problem was simple, and not easily solved: Morton’s life consisted of an early brilliant success followed almost at once by scandal and twenty years of frustration, disappointment, increasing opprobrium and deepening poverty — a long and dispiriting anticlimax.

Buddy De Sylva’s ordered changes in The Great Moment — carried out by editor Stuart Gilmore with suggestions from Chas. P. West of the Paramount editing department — threw all of that right out the window. Sturges later complained, “The studio decided that the picture should be cut for comedy. As a result, the unpleasant part was cut to a minimum, the story was not told, and the balance of the picture was upset.” Comparing his script with the picture as released, it’s plain that Sturges was exactly right. In the rush to get to the funny stuff (“The amazing, amusing romance of the hero of the roaring 1840s! Hilarious as a whiff of laughing gas!” bellowed the preview trailer), Paramount sacrificed much of the movie’s drama and may have even made the funny stuff less funny, because there was no longer the sense of relief that would make it welcome.

Even as it stands, truncated and vandalized by a clueless studio that had given up on it even before the cameras rolled (and would soon give up on Preston Sturges himself), The Great Moment is worth seeing. There are elements — like the persuasive period detail in the sets and costumes, and even in the typeface of posters and newspapers — that no editor could cut out, and which attest to how seriously Sturges took his story. Above all, there’s the simple dignity of Joel McCrea’s performance, and those of Betty Field, William Demarest and Harry Carey as the surgeon who believes in Morton. At the very least, as Bosley Crowther and John Lardner noted, the picture offers an interesting contrast to the standard reverent “marble man” portrayal so common in Hollywood’s treatment of important figures in science and medicine.

Preston Sturges’ fall from grace may have been inevitable, and when it came it was probably his own doing as much as anybody else’s. But it didn’t begin with The Great Moment, and the picture can’t be blamed for it. Uneven it may be, but Sturges conceived, wrote and filmed it at the height of his powers. What happened to it after that wasn’t entirely his fault.

.