A Jigsaw Mystery

I have an acquaintance who is a collector/dealer of movie memorabilia and ephemera. I’ve known this fellow for 54 years — or rather, let me rephrase that: I knew him 54 years ago, when his younger brother and I were roommates at Sacramento State College (now CSU Sacramento). The collector/dealer’s path and mine have crossed once or twice since then, but the brother, my former roommate, and I have remained reasonably in touch over the years.

I have an acquaintance who is a collector/dealer of movie memorabilia and ephemera. I’ve known this fellow for 54 years — or rather, let me rephrase that: I knew him 54 years ago, when his younger brother and I were roommates at Sacramento State College (now CSU Sacramento). The collector/dealer’s path and mine have crossed once or twice since then, but the brother, my former roommate, and I have remained reasonably in touch over the years.

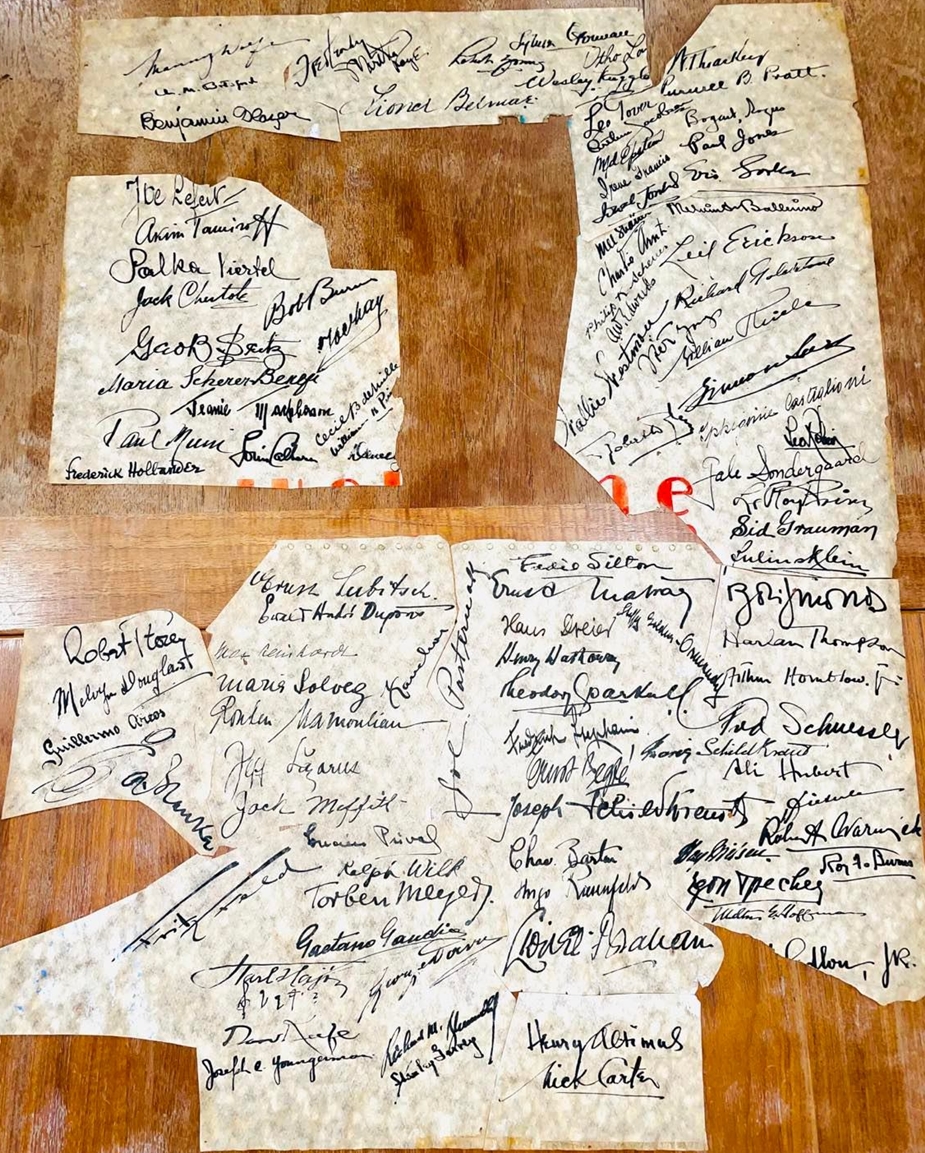

We met for lunch recently, and he shared this photo with me. As he told it to me over our sandwiches, these fragments were included in a bookcase-load of material that his older brother acquired last year from the estate of producer Jerry Wald. The bookcase’s contents mainly consisted of leather-bound copies of scripts to pictures Wald had produced (Peyton Place, Wild in the Country, Sons and Lovers, An Affair to Remember, etc.), but there were also these pieces of paper. They were from a single oversize sheet of parchment that had been cut up, cutting carefully around signatures, so that they could be put into a standard-size manila folder.

Unfortunately, as we can clearly see, the roster hasn’t survived intact. My friend tells me there are 100 signatures on what we have; I haven’t counted myself, but looking at it, that sounds about right. And they’re real signatures too, not reproductions, written in ink on parchment. No telling how many more there may have been; my own guess would be somewhere between 20 and 40.

Since that day at lunch, my friend has IM’d me with a correction. It turns out this incomplete jigsaw puzzle wasn’t among that recently-acquired Jerry Wald collection after all. On the contrary, the collector brother told him he’s had this for at least thirty years. So long, he says, that he’s no longer sure exactly where he got it — but he thinks it was among a large batch of film ephemera he bought from another dealer in Los Angeles in the 1980s, a batch that included scripts and business documents from the Hal Roach Studios.

On that narrow thread, I ran the picture by historian Richard M. Roberts, who specializes in silent comedy and knows more about Hal Roach’s career than Roach himself ever did. Richard didn’t know of any possible connection to Roach; he speculated only that the occasion was some sort of event at Paramount, since many (if not most) of the names here were Paramount employees at the time; beyond that he couldn’t say, though he did allow as how it was “an interesting bunch of autographs.”

It is indeed. And by the way, what do we mean by “at the time”? Well, as it happens, we can date this paper pretty narrowly based on internal evidence. At the due east point on the paper is the signature of Gale Sondergaard. Her first picture, Warner Bros.’ Anthony Adverse, was released in August 1936; it’s a cinch she wouldn’t have found herself in such illustrious company before then, and probably not till some time after, when she’d had a chance to make a splash with her showcase performance (she went on to win an Oscar for it). At the other end of the time-window, the southeast quadrant has the signature of composer Hugo Riesenfeld; he died on September 10, 1939 after a severe and lengthy illness. I don’t know how severe or lengthy that illness was, but let’s say it lasted most of 1939; let’s also say Gale Sondergaard didn’t break into the A-List until at least January 1937. Allowing that, it’s reasonable to say this roster is from sometime during 1937 or ’38.

But what was the occasion? At the center of the sheet there’s a wide gap, but we can glimpse the remnants of printed red letters that look like they may have formed the word “welcome”. Under the final “e” of “welcome” there’s another trace of red ink that suggests there were additional words, or perhaps a name, under that, and then there’s a third row consisting of white dots. This gap in the puzzle is what creates the mystery; if that weren’t missing, the purpose of this sheet of signatures might be crystal clear.

Even as it stands, there are interesting points to be gleaned from these signatures. Just under the w-e-l of “welcome” is a trio of noted German expatriate directors: Ernst Lubitsch, E.A. Dupont, and none other than that era’s supreme genius of the stage, Max Reinhardt himself. Two names below Reinhardt is Rouben Mamoulian (who directed High, Wide and Handsome at Paramount in 1937), but between them is what looks like someone named Maria Solvez. Who in the world could that be? For that matter, who are Nick Carter, Guillermo Areos, Manny Wolfe, Ralph Wilk, and several others whose handwriting is — to me at least — illegible?

Walter James Westmore of the Westmore makeup dynasty may have been billed as “Wally” in his 463 screen credits, but he signed this sheet “Wallie” (east of center, next to the big gap in the middle). Similarly, Cecil B. DeMille may have billed himself with an uppercase “D”, but here (across that gap from Wallie Westmore) he spells his last name “deMille”, just like brother William, niece Agnes, and the rest of their family always did. And in the southeast quadrant, between casting director Fred Schuessler (Gone With the Wind, Christopher Strong, King Kong [’33]) and costume designer Ali Hubert (The Life of Emile Zola, The Merry Widow [’34]), actor Joseph Schildkraut (who won an Oscar the same year as Gale Sondergaard) spells his first name “Josef”, the way his parents did when they named their newborn son in Vienna in 1896. And the Oscar-winning cinematographer we know as Tony Gaudio signs here (southwest, fourth row from bottom) with his given name of Gaetano.

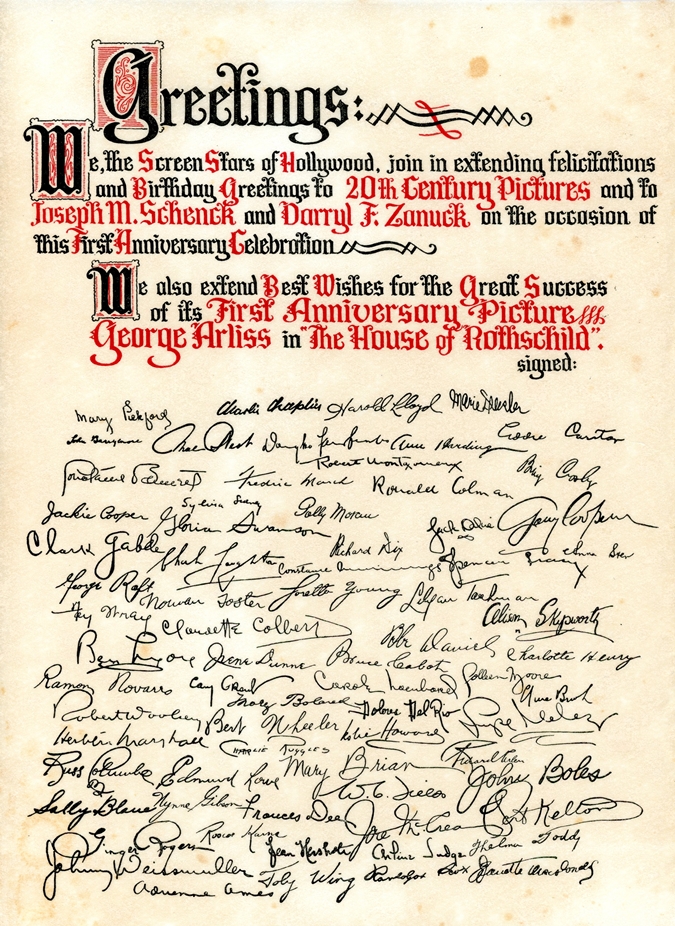

Adding to the mystery of it all is the fact that Hollywood people, then as now, didn’t as a rule go around collecting each other’s autographs, except on checks and contracts. So who collected all these, and why? The only clue I can offer is this — another collection of celebrity signatures on parchment, although here they’re lithographic reproductions, not the real McCoy. There’s no mystery to this parchment; it was an insert in the souvenir program for The House of Rothschild (1934) starring George Arliss, Loretta Young, Robert Young and Boris Karloff. As you can see, it’s a sort of birthday card, congratulating Joseph Schenck and Darryl F. Zanuck on the first anniversary of 20th Century Pictures and the release of Rothschild. From the top row (Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, Marie Dressler) to the bottom (Johnny Weissmuller, Adrienne Ames, Toby Wing, Randolph Scott, Jeanette MacDonald), it’s an impressive roster. (And about to become two less: When Rothschild premiered on April 7, 1934, Marie Dressler had only three-and-a-half months left; she would die of cancer on July 28. Later, in September, 26-year-old crooner Russ Columbo [fourth row from bottom] would be shot to death in a freak accident with an antique dueling pistol.)

Adding to the mystery of it all is the fact that Hollywood people, then as now, didn’t as a rule go around collecting each other’s autographs, except on checks and contracts. So who collected all these, and why? The only clue I can offer is this — another collection of celebrity signatures on parchment, although here they’re lithographic reproductions, not the real McCoy. There’s no mystery to this parchment; it was an insert in the souvenir program for The House of Rothschild (1934) starring George Arliss, Loretta Young, Robert Young and Boris Karloff. As you can see, it’s a sort of birthday card, congratulating Joseph Schenck and Darryl F. Zanuck on the first anniversary of 20th Century Pictures and the release of Rothschild. From the top row (Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, Marie Dressler) to the bottom (Johnny Weissmuller, Adrienne Ames, Toby Wing, Randolph Scott, Jeanette MacDonald), it’s an impressive roster. (And about to become two less: When Rothschild premiered on April 7, 1934, Marie Dressler had only three-and-a-half months left; she would die of cancer on July 28. Later, in September, 26-year-old crooner Russ Columbo [fourth row from bottom] would be shot to death in a freak accident with an antique dueling pistol.)

Clearly, I think, the parchment above was something along the lines of this, wishing somebody or something welcome the way this wishes happy birthday and congratulations. But who, why, and when…? Barring some lucky miracle, I guess we’ll never know. Pretty much everybody who signed it had left us by the end of the 1980s; actor Fritz Feld (southwest quadrant) made it to 1993, but he died of dementia, so who knows how much he would have remembered that late? I don’t know when my friend’s collector brother acquired the chart (neither, evidently, does he for sure), but by the time he did, there was probably nobody left to ask about it.

As Hollywood mysteries go, this one is comparatively trivial — but that doesn’t make it any less of a mystery. So I offer it here for study and speculation. Comments, hypotheses, ruminations are welcome. Meanwhile, I look forward to the day that some unexpected revelation, some offhand comment in some history, memoir or oral-history interview sheds light on what happened at Paramount (or wherever) in 1937 (or whenever) to make all those people write their names on a sheet of parchment to prove they were there.

UPDATE 9/20/22:

My friend Blair Leatherwood, who has access to a number of newspaper archives as part of his genealogical research, has been able to fill in a few gaps in our knowledge of these signatories:

Maria Solveg (not “Solvez”) was, like the three names above her — Ernst Lubitsch, E.A. Dupont, Max Reinhardt — a German expatriate. She and her husband Ernst Matray (Maria sometimes billed herself under her married name) first came to America with Reinhardt’s company in 1927, performing as a dance team and, in her case, actress. In 1933 the Matrays joined the exodus of German Jews who had the foresight and good fortune to flee Nazi Germany while the getting was good, first to France, then Great Britain, and finally the U.S. Significantly for our purposes, in August and September 1938 she was in Los Angeles working as Reinhardt’s assistant director on a production of Faust at the Pilgrimage Outdoor Theatre (today, the John Anson Ford Theatre) in the Hollywood Hills; that may narrow down even further the dating of this jigsaw puzzle. At some point, probably in 1940, Maria became a U.S. citizen and, in the words of Reinhardt’s son and biographer Gottfried, the Master’s “highly efficient assistant on Broadway”. Also a dancer and choreographer, she worked in some capacity (according to her Trivia page on the IMDb) on The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939), Pride and Prejudice (’40), Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (’41), White Cargo, Random Harvest (both ’42), Swing Fever (’43), Step Lively (’44), Murder in the Music Hall (’46) and The Private Affairs of Bel Ami (’47), among others. Whatever she did, she was not credited on most of those, either on screen or on the IMDb. By the late 1950s she was back in West Germany, the country having been safely de-Nazified, and she reclaimed her German citizenship in 1960. By then she had segued into screenwriting, and she worked steadily at that until 1992. She died in Munich in 1993, age 86.

Maria Solveg (not “Solvez”) was, like the three names above her — Ernst Lubitsch, E.A. Dupont, Max Reinhardt — a German expatriate. She and her husband Ernst Matray (Maria sometimes billed herself under her married name) first came to America with Reinhardt’s company in 1927, performing as a dance team and, in her case, actress. In 1933 the Matrays joined the exodus of German Jews who had the foresight and good fortune to flee Nazi Germany while the getting was good, first to France, then Great Britain, and finally the U.S. Significantly for our purposes, in August and September 1938 she was in Los Angeles working as Reinhardt’s assistant director on a production of Faust at the Pilgrimage Outdoor Theatre (today, the John Anson Ford Theatre) in the Hollywood Hills; that may narrow down even further the dating of this jigsaw puzzle. At some point, probably in 1940, Maria became a U.S. citizen and, in the words of Reinhardt’s son and biographer Gottfried, the Master’s “highly efficient assistant on Broadway”. Also a dancer and choreographer, she worked in some capacity (according to her Trivia page on the IMDb) on The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939), Pride and Prejudice (’40), Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (’41), White Cargo, Random Harvest (both ’42), Swing Fever (’43), Step Lively (’44), Murder in the Music Hall (’46) and The Private Affairs of Bel Ami (’47), among others. Whatever she did, she was not credited on most of those, either on screen or on the IMDb. By the late 1950s she was back in West Germany, the country having been safely de-Nazified, and she reclaimed her German citizenship in 1960. By then she had segued into screenwriting, and she worked steadily at that until 1992. She died in Munich in 1993, age 86.

Ralph Wilk (southwest quadrant, above Torben Meyer and Gaetano Gaudio) was born in Minneapolis in 1894 and lived in Los Angeles from 1927 until his death on June 9, 1949, age 55. According to his obituary in the L.A. Times, he was “West Coast manager of Film Trade”, but that was the result of either sloppy obituary writing or faulty information supplied to the paper; in fact, Ralph Wilk was the L.A. representative for Film Daily, a daily trade paper that published from 1918 to 1970.

Manny Wolfe (top left corner) was, from July 1932 to May ’39, head of the Paramount story department. Before that, he had been story editor at First National Pictures. From September 1928, First National was a subsidiary of Warner Bros.; flush with profits from The Jazz Singer and The Singing Fool, the Bros. had purchased a 58 percent share of First National to gain access to FN’s theater chain and Burbank studio complex (which remains the Warner Bros. Studio to this day). Warners eventually acquired a total of 87.5 percent, and First National became a wholly-owned subsidiary, with pictures released under both FN and Warners banners until 1936, when First National was dissolved. This is all necessary background to the following: While Manny Wolfe was at First National, across the lot at Warner Bros. there was a press agent and aspiring playwright named Norman Krasna. Krasna’s first produced play was Louder, Please, about two Hollywood publicity men who fake the disappearance of a movie star, with characters reportedly based on easily recognized persons around the Warners-First National lot. The play opened on Broadway on November 12, 1931 and ran for 68 performances. The Louder, Please playbill bears the credit, “A.L. JONES (By arrangement with Manny Wolfe) PRESENTS…” My guess is that Wolfe and Krasna knew each other at the studio, Krasna showed Wolfe his script, and Wolfe hustled it around New York, acting as Krasna’s unofficial agent and wangling an associate-producer credit on the production (not to mention pocketing a tidy sum in that “arrangement” with A.L. Jones). The play made enough of a splash that Krasna landed a writing gig at Columbia in 1932; it may have gotten Wolfe the job at Paramount as well. Whatever the case, Wolfe stayed at Paramount until May 1939, when he left “to assume a producer’s post at another studio.” What that studio was is not known, but Wolfe never seems to have earned a producer credit — or a writer’s for that matter. For all we know, he did fine work as a story editor, but that’s the kind of administrative position that leaves little trace except in a studio’s corporate records. Krasna, on the other hand, went on to a long and distinguished career on Broadway and in Hollywood as both writer and director, earning an Oscar for writing Princess O’Rourke (1943) and three other nominations before his death in 1984. What ever became of Manny Wolfe after 1939, I haven’t been able to ascertain.

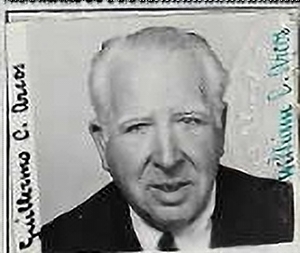

Guillermo Arcos (not “Areos”; due west, under Robert Florey and Melvyn Douglas) was born in Spain in 1880. He is, according to Blair, “listed on various documents (border crossing, WW II draft registration card, etc.) as an artist and as a jeweler. He also appears to have been a classical guitarist of some note.” At first I thought that, since Arcos would have been 60 in 1940, that draft card could not have been his (maybe a son, or even grandson) — but no, the card gives his birth date as July 8, 1880 (check!) and his “present” age as 62 (double check!). On IMDb, he has a handful of Spanish-language acting credits, plus uncredited (and probably non-dialogue) bits in A Message to Garcia and Ramona (both 1936). This photo is from his “Declaration of Intent”, a step in applying for U.S. citizenship, dated January 5, 1949. Also, an undated newspaper item from sometime in 1951-53 mentions him having given a guitar concert in Carnegie Hall “33 years ago” and credits him with having played incidental music for Robert Rossen’s The Brave Bulls (1951). Coming at this from another angle, on FindAGrave.com I found a listing for Pilar Arcos, born in Havana, Cuba in 1893. She was an actress and operatic soprano, and according to the listing, in 1917, while studying at the Conservatory of Madrid, she “married a guitar teacher/actor Guillermo Arcos.” (In early 1917 Guillermo would have been 36, Pilar 23. There may have been some urgency to their nuptials: Their first child, a boy William, was born October 28, 1917 in Houston, Texas.) In 1935, Pilar traveled to Spain to continue her singing career, but the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War drove her back to North America. Were she and Guillermo still together by then? Perhaps, or perhaps they had already separated. In any case, they were divorced in December 1939; on May 6, 1941 Guillermo married his second wife, Concepción. Guillermo died at 78 in 1959. Pilar outlived him by over 30 years; she died in 1990, age 96. Both died in Los Angeles, but they are not buried together. Pilar rests in Hollywood Forever Cemetery, beside her and Guillermo’s daughter Helen (1919-73), whom she outlived by 16 years. Guillermo’s resting place I was unable to locate.

Guillermo Arcos (not “Areos”; due west, under Robert Florey and Melvyn Douglas) was born in Spain in 1880. He is, according to Blair, “listed on various documents (border crossing, WW II draft registration card, etc.) as an artist and as a jeweler. He also appears to have been a classical guitarist of some note.” At first I thought that, since Arcos would have been 60 in 1940, that draft card could not have been his (maybe a son, or even grandson) — but no, the card gives his birth date as July 8, 1880 (check!) and his “present” age as 62 (double check!). On IMDb, he has a handful of Spanish-language acting credits, plus uncredited (and probably non-dialogue) bits in A Message to Garcia and Ramona (both 1936). This photo is from his “Declaration of Intent”, a step in applying for U.S. citizenship, dated January 5, 1949. Also, an undated newspaper item from sometime in 1951-53 mentions him having given a guitar concert in Carnegie Hall “33 years ago” and credits him with having played incidental music for Robert Rossen’s The Brave Bulls (1951). Coming at this from another angle, on FindAGrave.com I found a listing for Pilar Arcos, born in Havana, Cuba in 1893. She was an actress and operatic soprano, and according to the listing, in 1917, while studying at the Conservatory of Madrid, she “married a guitar teacher/actor Guillermo Arcos.” (In early 1917 Guillermo would have been 36, Pilar 23. There may have been some urgency to their nuptials: Their first child, a boy William, was born October 28, 1917 in Houston, Texas.) In 1935, Pilar traveled to Spain to continue her singing career, but the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War drove her back to North America. Were she and Guillermo still together by then? Perhaps, or perhaps they had already separated. In any case, they were divorced in December 1939; on May 6, 1941 Guillermo married his second wife, Concepción. Guillermo died at 78 in 1959. Pilar outlived him by over 30 years; she died in 1990, age 96. Both died in Los Angeles, but they are not buried together. Pilar rests in Hollywood Forever Cemetery, beside her and Guillermo’s daughter Helen (1919-73), whom she outlived by 16 years. Guillermo’s resting place I was unable to locate.

If any other information comes to light about the less-familiar names on the parchment, I’ll post another update — and another, and another, as needed. Watch this space!