“Don’t Stay Away Too Long…”

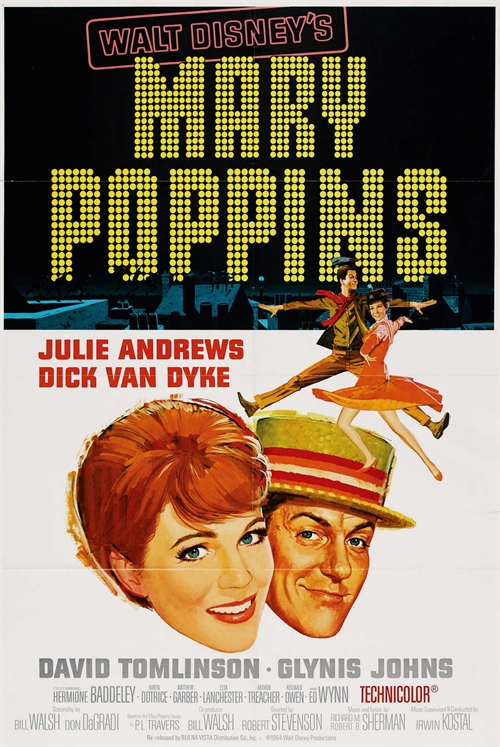

“G’bye, Mary Poppins,” says Dick Van Dyke’s Bert as the Practically Perfect Nanny sails away from No. 17 Cherry Tree Lane in Walt Disney’s Mary Poppins (1964). “Don’t stay away too long…”

“G’bye, Mary Poppins,” says Dick Van Dyke’s Bert as the Practically Perfect Nanny sails away from No. 17 Cherry Tree Lane in Walt Disney’s Mary Poppins (1964). “Don’t stay away too long…”

Well, she did stay away too long. But at long last Mary Poppins Returns has finally arrived, a sequel 54 years after the movie it sequelizes — surely some sort of record. I won’t go into great detail about the movie here, for two reasons: (1) the focus of Cinedrome is Classic Hollywood, not the current movie scene; and (2) the pleasures of Mary Poppins Returns are best discovered without any preparation beyond what you can get from having seen Mary Poppins in the first place.

But I will say this: Mary Poppins Returns is manifestly the best and most enduring movie of 2018. Does that sound brash? So be it. In my defense, I call as my witness generations yet unborn, who will know and cherish this picture long after whatever wins the Oscar this coming Sunday — and any other movie released last year — is a Trivial Pursuit answer that nobody gets. That this exquisite specimen of the moviemaker’s craft scores 78 percent fresh on Rotten Tomatoes and 66 on Metacritic only tells me that 22 percent of the critics on Rotten Tomatoes, and 34 percent on Metacritic, are fools who don’t know a great movie musical when it stares them in the face; I feel sorry for them. (Meanwhile, on RT, Bumblebee scores 93 percent fresh — which says all you need to know about the current state of film criticism.)

That’s all I have to say here about Mary Poppins Returns. I mention it mainly as a way to segue into a discussion of why it took 54 years for us to get a sequel to Mary Poppins at all. Because the fact is, we could have had Mary Poppins Returns, or something like it, fully half a century ago. It certainly would have starred Julie Andrews as Mary Poppins, and might even have had the rest of the cast — Dick Van Dyke, David Tomlinson, Glynis Johns, Karen Dotrice, Matthew Garber, right down to Reginald Owen as Admiral Boom. That this alternate-universe sequel never happened was due to two reasons: (1) Walt Disney died too soon, and (2) P.L. Travers lived much too long.

Before I get to Mary Poppins, a few words about Walt Disney. In the community college Film History and Introduction to Film classes I teach, I have a standard lecture I deliver when the subject comes up, as it always will, of Disney’s place in the art and history of moving pictures. Generally, that lecture runs something like this:

Before I get to Mary Poppins, a few words about Walt Disney. In the community college Film History and Introduction to Film classes I teach, I have a standard lecture I deliver when the subject comes up, as it always will, of Disney’s place in the art and history of moving pictures. Generally, that lecture runs something like this:

Some years ago, the arts editor on the paper where I was a film critic asked me: Who did I consider the most influential artist of the 20th century? I’m sure she expected me to name Pablo Picasso, or Salvador Dali, or Jackson Pollock. Or, moving to other arts, possibly James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, Eugene O’Neill or Ernest Hemingway. Or, sticking just to movies, maybe John Ford, Orson Welles, or even D.W. Griffith.

I didn’t even have to think about it. There’s not even a close second, I told her; the most influential artist of the 20th century is Walt Disney. All she could say to that was, “Well, if you consider Disney an artist…” “Well, if you don’t,” I told her, “you’re wrong.”

To me this is not a matter of opinion but a plain fact. Critics and artists may groan at the thought, but merely by inventing the theme park Walt Disney had an influence on American and world culture that Picasso or Hemingway could only dream of — and theme parks are far from all there was to Disney. If there’s one filmmaker from the 1920s — and ’30s, and ’40s, and ’50s, and ’60s — with whose movies you are reasonably familiar, it’s going to be Walt Disney.

Now I’m not talking about the Disney Company. I’m talking about Walt Disney the man — born 1901, died 1966. He died when your grandparents were the age you are now; I know because I’m old enough to be your grandfather and I was 18 when Walt Disney died. It was an occasion of not national, but world-wide mourning. Your grandparents grew up on Walt Disney’s movies. And so did your great-grandparents, and so did your parents — and so did you.

And, I’ll bet, so will your grandchildren. Someday you’ll be babysitting your grandkids, and you’ll turn on whatever people are using to watch movies when that day comes, and you’ll put on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs or Lady and the Tramp or Mary Poppins, and you’ll watch it with them, seeing it through a child’s eyes again just as you did when you first saw it at their age. And you’ll remember. That’s one of the things that makes Walt Disney one of the greatest artists America has ever produced.

And by the way, if anybody tells you otherwise, don’t listen to them, because there’s something wrong with their definition of art.

I transition now from my classroom lecture on Walt Disney back to a consideration of his final masterpiece.

I transition now from my classroom lecture on Walt Disney back to a consideration of his final masterpiece.

I saw Mary Poppins for the first time in early December 1964 at the Fox Senator Theatre, the first-run venue for all Disney pictures when they came to Sacramento. I remember it was the same night as the city’s Christmas Parade down K Street right in front of the theater; our showing turned out to be sold out, so my date and I killed a couple of hours watching the parade, window shopping, and helium-talking from a balloon we bought at a stand outside the entrance to F.W. Woolworth’s.

Finally, we got in to see the movie, and as we came out I had a thought that had never come to me after a movie before: “I’ve just seen a classic.”

Now I’d seen plenty of first-run classics up to that point: Cinderella, The War of the Worlds, The King and I, Mister Roberts, The Ten Commandments, Around the World in 80 Days, The 7th Voyage of Sinbad. But I was four to ten years old when I saw those, and four-to-ten-year-olds just don’t think in terms of classic anything. This, at age 16, was the first time the conscious thought came to me immediately as I left the theater.

I was a bit surprised, a couple of months later, when the Oscar nominations came out, and “Chim Chim Cher-ee” was nominated for best song. The song I’d been humming as I left the theater that night wasn’t “Chim Chim Cher-ee” but “Jolly Holiday”, the one Bert (and half the animal kingdom) sings as he and Mary Poppins stroll through the sidewalk chalk picture. The song’s “Once in Love with Amy” lilt was simply irresistible — plus, of course, it goes on for nearly 15 minutes.

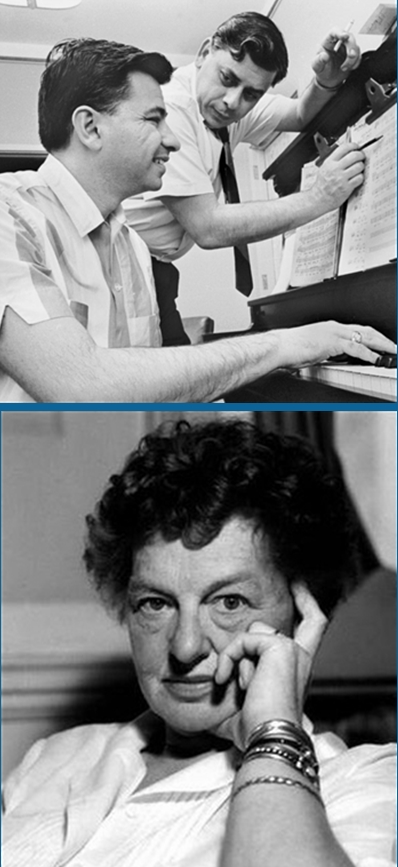

As all the world now knows, “Chim Chim Cher-ee” went on to win the Oscar, one of two that Robert and Richard Sherman won for writing Mary Poppins‘s music. By awards night I’d seen the picture a couple more times, and I better understood why “Chim Chim Cher-ee” won. It wasn’t until many years later, with decades of hindsight, that I came to believe as I do now: The nomination, and the award, should have gone to “Feed the Birds”. For my money, that’s the most beautiful song ever written for a Walt Disney picture, and that’s saying something. I’m not surprised that it was a particular favorite of Walt’s, or that he often asked the Shermans to play it to help him unwind at the end of a busy week. It’s probably no coincidence that it’s also the song most directly inspired by the original Mary Poppins stories — and the song that finally persuaded author P.L. Travers to go along with making Mary Poppins a musical.

And this brings me to Walt Disney’s secret weapon on Mary Poppins. Or weapons, I should say: Robert B. and Richard M. Sherman. Like writer Lawrence Edward Watkin on Darby O’Gill and the Little People, the Shermans were hired for a specific project, then assigned to others when that project had to go on a back burner. Watkin’s script for Darby O’Gill was delayed 12 years, during which he was put to work on Treasure Island, The Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men, The Great Locomotive Chase and others. The Sherman brothers didn’t have to wait quite that long to see Mary Poppins in production, but they were still sidetracked onto incidental songs for other projects — The Absent-Minded Professor, Big Red, The Sword in the Stone, The Miracle of the White Stallions, etc. — while Disney was courting P.L. Travers.

And this brings me to Walt Disney’s secret weapon on Mary Poppins. Or weapons, I should say: Robert B. and Richard M. Sherman. Like writer Lawrence Edward Watkin on Darby O’Gill and the Little People, the Shermans were hired for a specific project, then assigned to others when that project had to go on a back burner. Watkin’s script for Darby O’Gill was delayed 12 years, during which he was put to work on Treasure Island, The Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men, The Great Locomotive Chase and others. The Sherman brothers didn’t have to wait quite that long to see Mary Poppins in production, but they were still sidetracked onto incidental songs for other projects — The Absent-Minded Professor, Big Red, The Sword in the Stone, The Miracle of the White Stallions, etc. — while Disney was courting P.L. Travers.

“The Boys”, as they quickly became known around the studio, had been handed a copy of the first Mary Poppins book early on, and they were very much in synch with Disney’s thinking on Travers’ episodic, essentially plotless novel — when they compared notes, they saw that they and he had marked off the same six chapters for inclusion in a prospective movie — and story/song sessions with writer Don Da Gradi went well.

Bob and Dick Sherman were pleased with, and even proud of, what they’d written for Mary Poppins, and rightly so. Let’s not mince words; what they turned out is arguably the greatest score ever written for an original film musical. To my way of thinking, its only serious rivals are the ones for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and The Wizard of Oz. (To be honest, The Wizard of Oz would probably get most people’s vote. But it wouldn’t get mine.)

By the time Travers and Disney finally closed the deal — with Travers to receive $100,000 against five percent of the gross earnings from any eventual film, plus complete script approval — DaGradi and the Shermans were pretty pleased with what they’d come up with. They were sure (as Dick Sherman put it years later) that Mrs. Travers would be “bowled over” when she heard what they had for her.

They reckoned without P.L. Travers. “Bowled over” wasn’t in her vocabulary — unless it was something she did to other people. And she was about to do it to Don DaGradi and Robert and Richard Sherman. We’ll get into that next time.