“A Genial Hack,” Part 1

Henry Hathaway once said there was a time when he would have welcomed being called an “accomplished technician” or “studio workhorse.” “But the more I think about it, the more I realize it makes me seem to be a genial hack.” Hathaway was indeed an accomplished director, and he worked long and well in the studio system, first at Paramount, then for twenty years at 20th Century Fox. But he was nobody’s hack.

I guess I’ve always been a little over-protective of Henry Hathaway. Several years ago I bought one of those big encyclopedias that claim to tell you “everything you need to know” about American movies (actually, that should’ve tipped me off — the really good ones don’t do that). This one — well, let’s just say it was published under the aegis of a very prestigious group of people. The first thing I did was to turn to the biographical section on directors to see what they said about Hathaway. He wasn’t listed. I scanned back and forth across the pages, just to make sure I wasn’t seeing what I thought I didn’t see. Then I closed the book and never opened it again; when the donation truck came around, into the bin it went.

Whoever compiled that book, I didn’t expect them to admire Hathaway as much as I do — I don’t suppose anyone does that. But I wasn’t going to let them act as if he never existed. Not if they wanted to take up space on my bookshelf.

I first became aware of Hathaway the night I saw How the West Was Won at the Orpheum Theatre in San Francisco. I was just beginning to notice movie directors; I wasn’t one of those film-buff prodigies who could discourse on the Auteur Theory at an age when other kids were reading Fun with Dick and Jane. I knew about Cecil B. DeMille, and Alfred Hitchcock, but everybody knew who they were. And I knew about John Ford, one of the other credited directors on How the West Was Won. George Marshall, the third director, not so much (though I knew about Destry Rides Again, one of his pictures). But Hathaway’s name caught my eye for the simple reason that the program said he was born in Sacramento, where I lived.

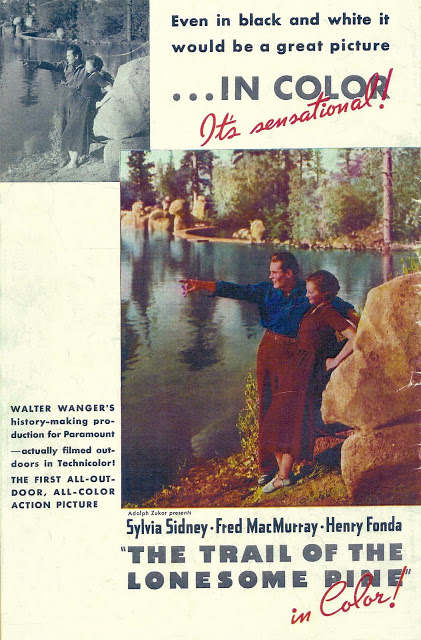

Now that I knew his name, I began to notice that Henry Hathaway directed some movies that I’d always loved. The Trail of the Lonesome Pine (1936), which I saw on a reissue at the age of eight. North to Alaska (1960). And others that I’d seen on TV in the 1950s and early ’60s: Call Northside 777 (1948), Down to the Sea in Ships (1949), Fourteen Hours and The Desert Fox (both 1951). Others would later make the list: The Sons of Katie Elder (1965), Nevada Smith (1966), True Grit (1969). And, of course, How the West Was Won itself.

Hathaway was born in Sacramento (March 13, 1898), but it wasn’t exactly his home town; it was just where his actress mother happened to be on the point in her tour when his time came. (Traveling theater companies didn’t offer maternity leave in 1898.)

Henry Hathaway may well be the only hereditary Belgian nobleman who ever made it as a Hollywood movie director. His name at birth was Marquis Henri Leopold de Fiennes, a title he inherited through his father. Hathaway said his father’s name was Henry Rhody, but he appears to have been a bit of a theatrical jack of all trades — advance man, stage manager, actor — under the name Rhody Hathaway. Hathaway said his mother’s maiden name was Jean Weil, though other sources say she was born Marquise Lillie de Fiennes in Budapest in 1876. I’m inclined to take her son’s word on this point, but whatever the case, Mom acted under the name Jean Hathaway, and before long little Henri Leopold had taken it too. (Also, Henry’s paternal grandfather was supposed to secure the Hawaiian Islands for Belgium in the 1860s, and settled in San Francisco when the deal fell through. Considering how Belgium later administered its colonial holdings in Africa’s Congo, native Hawaiians might have cause to be grateful that Hathaway’s grandfather failed.)

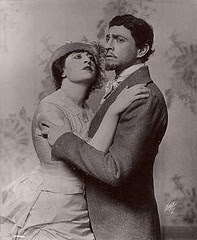

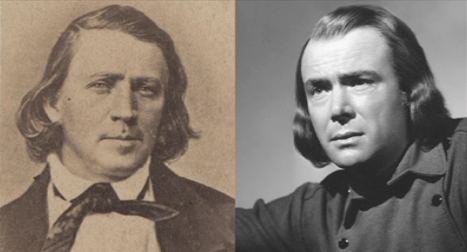

Jean Hathaway seems to have been no ordinary woman. Only 22 when her son was born, by the time they both entered movies in 1911 or ’12, she had moved into “character parts” — somebody’s mother or aunt or older sister, or a villainess if one was called for. I don’t know how old she is in this picture, but it seems to me she’s more or less the same age as Henry in the picture below, taken on the set of The Trail of the Lonesome Pine, when he was 37.

That’s Henry standing on the left, next to Nigel Bruce. (At the table are Fred MacMurray, Henry Fonda and Fred Stone.) You can see that Henry certainly took after his mother.

In more ways than one. Rhody Hathaway seems not to have had the theater bug as severely as his wife — it’s never been the most stable career path, and it was downright perilous then. Henry’s father eventually left the biz and got into electronics — a more obviously burgeoning field in the 1910s and ’20s — working on an early x-ray machine. Jean continued to tour, occasionally getting stranded, in those pre-Equity days, when a company would go bankrupt on the road.

When this happened to her in 1911 in San Diego, leaving her broke with no way to get home, she cast about for some kind of job to earn train fare, and landed with the American Film Company in nearby La Mesa. Moviemaking was a footloose operation in those days, grinding out quickie one-reelers for the nickelodeons, but here was steady work in one place, so when she saw that it was going to pan out, she sent for Henry and his sister, who had been living with relatives in San Francisco.

Henry started out as a child actor — usually, he said, playing the kid in the opening scene who grows up to be the leading man. As he grew into his teens, he went to work at Universal, first as a laborer, then a prop man. (His last acting credit was in 1917, just before a short army stint stateside during World War I.) After mustering out of the army, he went back to movies as a prop man at Goldwyn Studios, then Paramount, where he worked as an assistant director throughout the 1920s, learning the craft under men like Josef von Sternberg and Victor Fleming. He graduated into directing in 1933, remaking silent Paramount westerns for sound — only on a lower budget, re-using footage from the silent versions wherever possible. (“I had to have the new leads costumed the same as the silent players.”)

Few directors had a career to compare with Henry Hathaway’s. He literally got in on the ground floor, before there was even a Hollywood as we know it today. He made his first movie in 1911, his last in 1974. He started out digging ditches and lugging equipment, and rose to directing huge projects with the biggest stars in the business. Along the way he pioneered sound, color and narrative Cinerama, the wonder of the age throughout the 1950s.

The performances he got from his actors are nothing to sneeze at either. He made a star of Richard Widmark in Kiss of Death (1947) and landed an Oscar for John Wayne in True Grit. And Dorothy Lamour, that sweet, ever-befuddled foil for Bob Hope and Bing Crosby, never gave a good dramatic performance for any other director, but she did it for Hathaway twice, in Spawn of the North (1938) and Johnny Apollo (1940).

I’ll have more to say about some of Henry Hathaway’s movies later on. For now, take this as an introduction to the man, something to plug the hole in that encyclopedia I mentioned earlier — just in case you happened to buy it from the thrift store I donated it to.

“A Genial Hack,” Part 2: The Trail of the Lonesome Pine

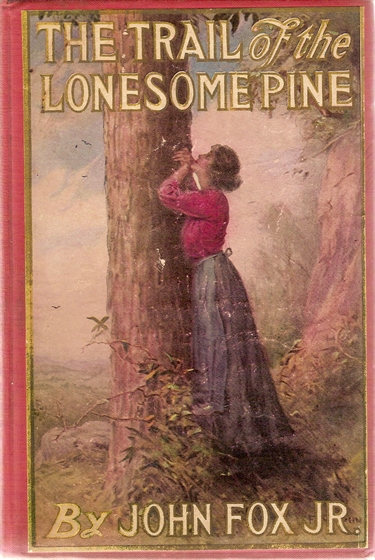

The book was a phenomenal success. Records being what they were in those days, it’s hard to know exactly how many copies it sold. Surely in the hundreds of thousands, probably more; one source I found said 1.3 million, at a time when a million-selling book was something to write home about. In any case, here’s what Fox’s novel looks like. It may look familiar; if you’ve spent any time at all in a used bookstore, you’ve probably seen several copies. They’re not uncommon, even after 102 years, and they’re not expensive; no telling how many times used copies like this one have been sold, resold, and resold again since 1908.

The novel has gone in and out of print (it’s currently in), but its popularity has never really gone away. In the wake of the 1936 movie, there was a stage adaptation that is still performed every summer (“official outdoor drama of the Commonwealth of Virginia”) in Big Stone Gap, Va., where Fox died in 1919. Fox managed somehow to come up with one of those perfect titles. Even if you’ve never heard of him or his books (and these days, most people outside Virginia and Kentucky haven’t), you feel as if you know what the story’s about the minute you hear it. The Trail of the Lonesome Pine — all by themselves, the words conjure up a time, a place, and a heart-on-the-sleeve sentimental romanticism.

The movie Hathaway and writer Grover Jones made for producer Walter Wanger in the late summer and early autumn of 1935 was the last, but not the first from Fox’s book; there had been three silent ones, in 1914, 1916 and 1923. There hasn’t been a movie from Fox’s novel since then. The reason could mainly be changes in public taste — romantic backwoods melodramas aren’t the surefire thing they were at the turn of the 20th century. But it could also be simply that the amazing success of Hathaway’s version — reinforced by numerous reissues over the next 20-plus years — made it an indelible act to follow.

The movie was a smash. It was only the second feature in Herbert Kalmus’s newly perfected three-strip Technicolor, and the first shot outdoors, in scenery made for Technicolor — Big Bear, in California’s San Bernardino Mountains. My mother saw The Trail of the Lonesome Pine as an 11-year-old girl, and she said her most vivid memory of it was Sylvia Sidney’s blue eyes. I know what she meant; I saw Lonesome Pine on a theatrical reissue when I was eight, and I remember Sylvia Sidney’s eyes just as clearly as my mother did. This frame from the Universal Home Video DVD release shows (to those of us who remember it in theaters) that it doesn’t do full justice to the IB Tech. But even to those who don’t remember it that way, it gives a powerful hint, and it’s a beautiful shot in its own right. It’s easy to believe that audiences in 1936 weren’t accustomed to seeing things like this on their movie screens.

Or this. Here’s the first sight that greeted audiences after the opening credits, and it suggests a canny calculation in the movie’s color scheme. Blue was one color that the old two-color system simply couldn’t handle; the closest it could come was a sort of turquoise. Even oceans and skies came out a sort of yellowish green. And the credit sequence to Lonesome Pine — names carved into tree trunks in a thick forest — seems almost deliberately weighted toward the red range that had been the old Tech’s long suit. It’s as if the credits are designed to invoke Your Father’s Technicolor, to remind you of what Technicolor couldn’t do just before showing you what it can do now. The effect, even now, is spectacular.

The first full-Technicolor feature, Rouben Mamoulian’s Becky Sharp, also made experiments with color, but it was setbound and stagy where Lonesome Pine was sun-splashed and outdoor-crisp. More to the point, Becky Sharp was a financial disappointment, if not a flop. People began to wonder if Technicolor could justify the extra expense. By the end of Lonesome Pine‘s second week in New York, the jury was back on that question. The Trail of the Lonesome Pine belongs in the history books for having gone far to prove the viability of color in commercial moviemaking.

And Lonesome Pine outdoes Becky artistically, too. The plain truth is, the subtleties and nuances of Thackeray’s Vanity Fair resist compression to the length of a single feature (in Becky Sharp‘s case, only 83 minutes), while a broad-stroke melodramatist like John Fox is tailor-made for it. Hathaway’s movie may not have the reach of Mamoulian’s, but it has a surer grasp. And audiences still respond to it emotionally, just as they did in 1936 (and ’49, and ’56). For that reason, though it’s 16 minutes longer than Becky Sharp, it feels half an hour shorter.

The raw emotionality of the story, set against the mountain feud between the Tolliver and Falin clans, makes the movie powerful. Even if it looked like outmoded hokum to the sophisticated critics of the day, audiences ate it up, and they still do. The emotion is close to the surface, whether full-bore in Sylvia Sidney’s screaming for blood or in the quiet moment here (Hathaway’s favorite shot in the entire picture). I won’t explain what’s happening, you’ll have to discover that for yourself. But if it doesn’t bring tears to your eyes, as they say, check your pulse. John Ford and Jean Renoir at their best could never have bettered the poetry of this heartbreaking shot.

“A Genial Hack,” Part 3: Peter Ibbetson

Every now and then in the 1930s (and more often than you might think) the Hollywood factory would turn out a picture that just didn’t fit the mold, one that seems in retrospect out of step with the reigning star system, the house style of its studio, the temper of the times — or a combination of all three. Lewis Milestone’s The General Died at Dawn was like that, and Warner Bros.’ Victorian-ornate A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and 1934’s Death Takes a Holiday. (For that matter, so was King Kong.) “Miracle pictures,” I call them; the fact that they’re as good as they are — that they were made at all — seems almost to violate the laws of Hollywood physics.

Every now and then in the 1930s (and more often than you might think) the Hollywood factory would turn out a picture that just didn’t fit the mold, one that seems in retrospect out of step with the reigning star system, the house style of its studio, the temper of the times — or a combination of all three. Lewis Milestone’s The General Died at Dawn was like that, and Warner Bros.’ Victorian-ornate A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and 1934’s Death Takes a Holiday. (For that matter, so was King Kong.) “Miracle pictures,” I call them; the fact that they’re as good as they are — that they were made at all — seems almost to violate the laws of Hollywood physics.

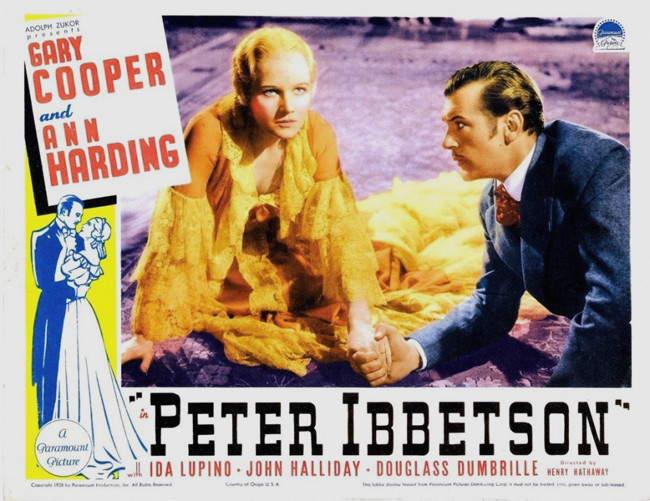

In 1935, fresh off the roaring success of his first A-picture, The Lives of a Bengal Lancer, Henry Hathaway turned out one of these miracle pictures for Paramount. Peter Ibbetson is unlike any other movie Hathaway ever made. It’s unlike any other movie its star, Gary Cooper, ever made. Until the 1940s, when the trauma of World War II spawned a sub-genre of movies concerned with immortality and the afterlife (Here Comes Mr. Jordan, Heaven Can Wait, A Guy Named Joe, The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, etc.), it was almost unique. It’s impossible to dismiss Peter Ibbetson once you’ve seen it. This post has been delayed because I want to be very careful what I write about it, to get what I want to say exactly right. And also because, revisiting Hathaway’s haunting, lyrical movie, I can’t restrain myself from wanting to watch it over and over — sometimes straight through, sometimes hopping from one favorite moment to another.

If Peter Ibbetson seemed strange to audiences in 1935, it probably wasn’t because it was so spiritual or ethereal, but because it was so old-fashioned. It must have looked like something D.W. Griffith would have done in his heyday (in fact, looking back now, it seems odd that Griffith never did). The story originated in an 1891 novel by George du Maurier, grandfather of Daphne du Maurier. The strain of gothic romance that runs through Dame Daphne’s novels (Rebecca, Jamaica Inn) can be traced to her grandfather, even though he’d been dead over a decade when she was born. Peter Ibbetson, riding the wave of spiritualism and occultism that was cresting in the late Victorian Era, was a modest success, and du Maurier followed it in 1894 with the hugely successful Trilby (in which he contributed the term “Svengali” to the English language).

In the late 1910s playwright John Nathaniel Raphael and actress-director Constance Collier adapted Ibbetson into a play. It was a hit on the London stage, and in 1917 Collier co-starred with the young John Barrymore on Broadway, as du Maurier’s star-crossed lovers who meet every night in their dreams. It was this version of du Maurier’s rambling and undisciplined tale that provided the framework for Vincent Lawrence and Waldemar Young’s script for Hathaway and his stars Gary Cooper and Ann Harding.

Hathaway wasn’t originally assigned to direct Peter Ibbetson; the job was supposed to go to Richard Wallace. Wallace (born, like Hathaway, in Sacramento) had just finished The Little Minister with Katharine Hepburn, and Ibbetson seemed like a good fit. But Gary Cooper, antsy over the script’s offbeat quality, insisted on Hathaway instead. (Hathaway was one of Cooper’s best friends and his favorite director, and eventually directed more of Cooper’s movies than anyone.) Shuffled off onto Annapolis Farewell, which had been Hathaway’s next slated assignment, Wallace flew off for the film’s Maryland location and was badly injured (though not killed) when his plane went down in Macon, Georgia; Annapolis Farewell was eventually directed by Alexander Hall.

Henry Hathaway didn’t often work with child actors, but when he did, he got good results (Spanky McFarland in The Trail of the Lonesome Pine, Dean Stockwell in Down to the Sea in Ships). And so it was with Dickie Moore and Virginia Weidler in Ibbetson. They play Cooper and Harding as kids, “Gogo” and “Mimsey”, when their souls become mated for life. The first of the movie’s poetic moments comes when the two are about to be separated, as Gogo’s gruff uncle is taking him from his Paris home after his mother’s death, to be raised in England; a closeup shows Weidler timidly taking Moore by the hand.

When they meet years later, Gogo is now Peter, a promising young architect, and Mimsey is Mary, the Duchess of Towers, whose husband the duke (John Halliday) has hired Peter to redesign the stables on his estate. At first they don’t recognize one another, but the realization comes one morning during Peter’s stay at the estate, when the two find they have shared the same dream the night before, of being caught in a sudden storm during a carriage ride.

It is in its last third that Peter Ibbetson becomes something rare and unforgettable, when the lovers are parted once again as Peter is sent to prison. The most sensible and satisfying change that Raphael and Collier made in their play was to alter the crime for which Peter goes away. In du Maurier’s novel, he cold-bloodedly murders the “uncle” who raised him when he learns that the man is really his biological father, a notorious rake who seduced and abandoned his mother, leaving her to die brokenhearted in Paris.

In the play and movie, the “crime” occurs in a confrontation with the drunken Duke of Towers. The duke brandishes a pistol, and Peter, accidentally and in self-defense, bashes his brains out with a chair. Tormented by the separation and tortured in prison, his back broken by a sadistic guard, Peter surrenders to despair, hoping only for death.

But Mary appears to him and proves that this is no delirium; they are really together in a dream, though separated by distance, stone and iron.

“You needn’t be afraid, Peter,” she says. “The strangest things are true, and the truest things are strange.”

“You needn’t be afraid, Peter,” she says. “The strangest things are true, and the truest things are strange.”

Peter gains courage to live for the nighttime, when they can be together. In du Maurier’s book, they spend years gallivanting through time and space, unfettered by a world that has grown unreal to them. (It gets more than a little tedious, truth be told.) In the movie, this is distilled into a transcendent 16-minute sequence, luminously photographed by Charles Lang (on some of the same locations Hathaway would soon showcase in Lonesome Pine), that takes Peter and Mary to a world of their own, brilliant with sunshine that contrasts sharply with his dank prison cell and her stately, forbidding manor house. It’s the climactic movement of a lush visual symphony.

Peter Ibbetson is an almost ineffably sublime experience. Never mind that Gary Cooper, playing an Englishman, never even tries to hide that Montana accent that persuaded some people all through his career (and still does) that he couldn’t act at all. His faith in Hathaway is well-justified, for this is an extraordinarily well-directed movie, and one of his most touching performances. Ann Harding, despite her golden beauty, was a cold fish on screen (“an absolute bitch,” according to Hathaway). It’s no coincidence that her only Oscar nomination came for playing the snooty older sister in Holiday (1930). She bridled at working with Cooper, feeling he gave her nothing in his acting, but she was wrong. In Ibbetson she glows in the reflected warmth of Cooper’s performance; we love her because he does.

The look of the movie is as sublime as Cooper’s acting. If Lives of a Bengal Lancer shows what Hathaway learned from Victor Fleming, Ibbetson shows the effect of having worked with Josef von Sternberg. Hathaway and Lang modeled their lighting on Rembrandt (“He taught you not to be afraid of the dark.”), and the compositions reinforce the romantic yearnings of the story. See how often the two lovers are separated by iron bars, walls — even, as children, the rails of the cast-iron fence between their homes. When, in dreams, they walk through the bars to be together, it’s a simple trick that any amateur shutterbug could explain to you, but it’s so perfectly right that it takes your breath away.

The look of the movie is as sublime as Cooper’s acting. If Lives of a Bengal Lancer shows what Hathaway learned from Victor Fleming, Ibbetson shows the effect of having worked with Josef von Sternberg. Hathaway and Lang modeled their lighting on Rembrandt (“He taught you not to be afraid of the dark.”), and the compositions reinforce the romantic yearnings of the story. See how often the two lovers are separated by iron bars, walls — even, as children, the rails of the cast-iron fence between their homes. When, in dreams, they walk through the bars to be together, it’s a simple trick that any amateur shutterbug could explain to you, but it’s so perfectly right that it takes your breath away.

Some seven years later, Hathaway directed Constance Collier, now a grand dowager of the theater, in The Dark Corner. One day, during a break on the set, she suddenly said, “Henry Hathaway. My God, you’re not the Henry Hathaway who made that dreadful picture out of my play Peter Ibbetson with that horrible man — that Gary Cooper. My God, you’re not that Hathaway!” He said, “I sure am,” and Collier dropped the subject. Hathaway was proud of his movie; he couldn’t understand why Collier was so offended. Neither can I.

Nor could a lot of people. Ernst Lubitsch said it was one of the best-directed movies he’d ever seen. To Luis Bunuel, it was “one of the world’s ten best films;” to Andre Breton, “a triumph of surrealist thought.” Even Pauline Kael, who called it “an essentially sickly gothic,” conceded Hathaway “brings off some of the ethereal moments, and the film tends to stay in the memory.”

It’ll stay in yours, too.

POSTSCRIPT: This concludes the opening salvo in my tribute to Henry Hathaway. I’ll post on some of his other movies from time to time, movies you may well have seen without knowing who directed them — some acknowledged classics, some neglected gems, some perhaps less successful ventures that still have things worth seeing. If Hathaway is fated to remain neglected and ignored for his tremendous body of work, I hope it won’t be because I never spoke up to defend him.

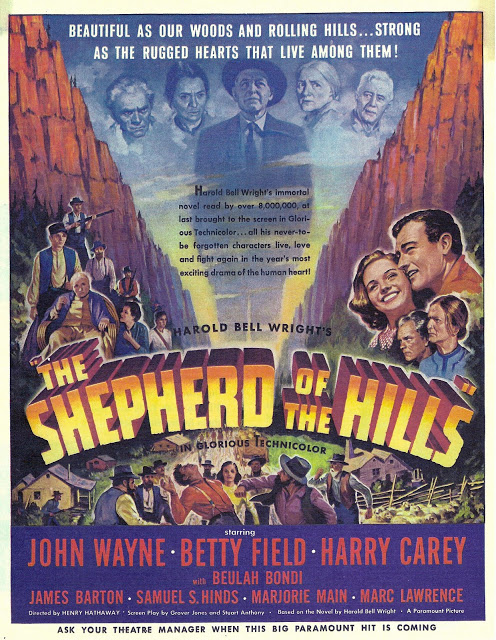

Films of Henry Hathaway: The Shepherd of the Hills

Harold Bell Wright was a 35-year-old minister in the Disciples of Christ Church in Redlands, Calif. when he resigned his ministry in 1907 after the success of The Shepherd of the Hills, his second novel. Thereafter, he devoted himself full-time to writing as a way of spreading the Gospel (of decency, of hard work, of caring for the downtrodden) by other means.

You can get the whole story at Gerry Chudleigh’s comprehensive Harold Bell Wright Web site, including this page specifically dedicated to movies from Wright’s stories and novels. The Reader’s Digest version, as brief as I can make it, is that Wright, dissatisfied with a 1916 picture based on his Eyes of the World, decided to film his books himself. To that end he formed the Harold Bell Wright Story-Picture Corporation with his publisher, Elsbery Reynolds. The company made only one picture, The Shepherd of the Hills in 1919, adapted and directed by Wright himself. Perhaps the picture was not well-received, perhaps the company was torn asunder by the falling-out between Wright and Reynolds when the writer decided to sign with a different publisher. Whatever the cause, by 1922 the two men were on the outs and the Harold Bell Wright Story-Picture Corporation was no more.

So Wright may well (and I wouldn’t blame him) have sighed and rolled his eyes at what was happening to his books in Hollywood, being powerless to alter it. Then again, his curiosity may have drawn him to check out what Paramount did in 1941 with his most popular novel; if so, perhaps he took comfort that, unlike that cheapskate Lesser, at least Paramount brought Technicolor, an “A” budget, and top-shelf talent to the table — beginning with Henry Hathaway and scenarist Grover Jones.

Hathaway and Jones had collaborated successfully before, having first worked together on 1929’s The Virginian, where Hathaway served as assistant to Victor Fleming. When Hathaway himself became a director, Jones worked with him on the scripts of The Lives of a Bengal Lancer, The Trail of the Lonesome Pine and Souls at Sea. Shepherd of the Hills would be their last picture together; on September 24, 1940, while Shepherd was in post-production, Grover Jones died of complications following surgery. He was 46.

The script for Shepherd is credited to Jones and Stuart Anthony, in that order. I don’t know how much the two collaborated; maybe they didn’t. Anthony may have been the writer brought in to add some connective scenes after Hathaway left the picture (more about that later). In any case, the script jettisons all the melodramatic curlicues of Harold Bell Wright’s plot and leaves only a few basics, expanding and elaborating on those.

The setting is a remote mountain valley (Wright was living in the Ozarks of southern Missouri when he began the book) where the sparse populace ekes out a hardscrabble life based on subsistence farming, small-scale sheep ranching, and running moonshine past impotent federal authorities. Everyone cowers under a pall of superstitious misery centered on an empty homestead called Moaning Meadow, where walks (so they say) the ghost of a woman whose man left her to die of a broken heart. Feeding off this festering unhappiness like a spider is the dead woman’s sister Mollie Matthews (Beulah Bondi); she has raised her nephew, Young Matt (John Wayne), on a diet of hate, telling him every day that the curse on all their heads can be lifted only when he finds and kills the unkown man who brought it on: his father. Matt is a gentle, tormented soul who doesn’t relish the thought of killing, but he sees no way out; not even his growing feelings for pretty Sammy Lane (Betty Field), who plainly adores him, can be allowed to sway him from the task Aunt Mollie has set for him.

Into all this walks kindly old Daniel Howitt (Harry Carey), a man of some (though mysterious) means with a hankering to settle down there. He befriends Sammy Lane and her father Jim, staying with them until he persuades the Matthewses to sell him Moaning Meadow. His effect on the whole valley is nearly miraculous: he heals the sick (treating Jim Lane’s wounds when he is shot by a federal agent), raises the dead (saving a little girl who nearly chokes to death while her grieving parents look helplessly on), and makes the blind to see again (sending an old woman to the city for an operation to restore her eyesight). As Howitt tends his flocks on Moaning Meadow, folks roundabout come to regard him, both literally and figuratively, as a good shepherd.

It isn’t long before Sammy figures out what has long since dawned on us: Daniel Howitt is Young Matt’s long-lost father, the man Matt has sworn to kill. What happens from there constitutes the last act of The Shepherd of the Hills.

Whether the credit goes to Grover Jones or Stuart Anthony (my own money’s on Jones), the script for Shepherd has passages that rise to a kind of mountain poetry, like something by James Whitcomb Riley or an Ozark Robert Burns. We hear it in the everyday speech, when a mother tells the village storekeeper about her sick daughter: “I put a dried tater chip and two crawdad legs in her bed. But she’s still got that seldom feelin’, complainin’ from head to heel.” And at more important moments, such as when Sammy first tells Mr. Howitt about Moaning Meadow: “That’s where the ha’nt comes from. Frogs as quiet as graverocks, and the lake comin’ from nowhere, and the trees don’t rustle, and the flowers grow big but they don’t have pretty smells.” Then, when Howitt disregards her advice and buys the meadow: “On account o’ ye disobeyin’ me ye bought a unhappy land. Moanin’ Meadow! Won’t nobody come an’ pay ye company there, nor warm by your fire with ye … Them that goes in there has daylight dreams they allus disremembers! An’ there’s pizen plants an’ pokeberries, an’ nightshades dancin’ with the bats!” The dialogue paints us a picture of an isolated people without schooling in the rules of grammar, but who have learned to make their language measure the deepest reaches of their simple hearts.

Casting Harry Carey and John Wayne as father and son was an inspiration, and it resonated for audiences in 1941 as much as it does for us today, if for a slightly different reason. Wayne was still sweeping along on the momentum of his A-picture breakthrough in Stagecoach after nearly a decade in Poverty Row horse operas. It’s a bit of a myth that John Ford and Stagecoach made a star out of an “unknown” John Wayne. He was already a star, albeit in the kind of movies that didn’t play Radio City or the Roxy, or win Oscars or make the New York Times 10-best list. But after Stagecoach Wayne was batting in a whole different league. He reported to the set of Shepherd directly after wrapping Seven Sinners with Marlene Dietrich over at Universal. The Duke Wayne of Santa Fe Stampede or King of the Pecos couldn’t have shot his way into a Dietrich picture; that’s what Stagecoach did for John Wayne. And in 1941 the Wayne persona was still malleable; studios were still experimenting with what kind of vehicles best suited this tall, handsome, earnest young man. The persona wouldn’t really become rigidly set until 1948, with Red River, when writer Borden Chase handed Wayne the script and said, “Here’s a part you can play for the next twenty years.” (Which Wayne pretty much did.)

The best of the lot just may be Betty Field in Shepherd. Her Sammy is feisty and independent, uneducated and superstitious — muttering half-heard incantations, drawing symbols and spitting in the dirt before venturing into Moaning Meadow — but no fool. She knows her own world inside out, and when her moonshiner father stumbles home with a revenuer’s bullet in his side, she calmly goes about her business, slicing bacon and singing as if nothing had happened, until the suspicious lawmen have gone their way. When she meets Daniel Howitt, she’s wary at first, but she soon sees the good in the man and vouches for him to others; when he seeks to cash a check for the unheard-of sum of a hundred dollars, the storekeeper blanches, but says, “Sammy’s say-so is all right with me. I’ll look around.” Sammy senses the tender heart of Young Matt, too, and struggles to reach it, battering in futile frustration at the crust of hatred so carefully planted and tended by the malicious Aunt Mollie.

The best of the lot just may be Betty Field in Shepherd. Her Sammy is feisty and independent, uneducated and superstitious — muttering half-heard incantations, drawing symbols and spitting in the dirt before venturing into Moaning Meadow — but no fool. She knows her own world inside out, and when her moonshiner father stumbles home with a revenuer’s bullet in his side, she calmly goes about her business, slicing bacon and singing as if nothing had happened, until the suspicious lawmen have gone their way. When she meets Daniel Howitt, she’s wary at first, but she soon sees the good in the man and vouches for him to others; when he seeks to cash a check for the unheard-of sum of a hundred dollars, the storekeeper blanches, but says, “Sammy’s say-so is all right with me. I’ll look around.” Sammy senses the tender heart of Young Matt, too, and struggles to reach it, battering in futile frustration at the crust of hatred so carefully planted and tended by the malicious Aunt Mollie.Films of Henry Hathaway: Down to the Sea in Ships

In 1949 Henry Hathaway made one of the best movies of his long career. In it, his three stars, Richard Widmark, Lionel Barrymore and Dean Stockwell (and for that matter, most of the supporting cast) each gave one of his own best performances. Down to the Sea in Ships is in fact one of the finest movies ever to come out of the Hollywood studio system, and almost nobody has ever heard of it.

I know I run the risk of overselling the product here, but I simply don’t understand why Down to the Sea in Ships isn’t one of the best-loved movies of all time. When the talk turns to the great seafaring stories of the screen — Treasure Island, Mutiny on the Bounty, Captains Courageous, Moby Dick et al. — it’s a mystery to me why Down to the Sea in Ships never comes up. If there are such things as flawless movies, and there surely are, Henry Hathaway’s Down to the Sea in Ships is one of them.

I say “Henry Hathaway’s” to distinguish this picture from the other Down to the Sea in Ships, from 1922. That one made a star out of Clara Bow, and curiously enough, it’s available on home video — no doubt because it’s in the public domain, while Hathaway’s picture is still under copyright and quarantined in the 20th Century Fox vault. In the 1960s and ’70s it was the other way around: Down to the Sea in Ships (1922) was gone and long forgotten, but if your local TV station had a decent film library and you were willing to stay up till two or three in the morning, you could count on seeing Down to the Sea in Ships (1949) two or three times a year.

Before we leave the subject of Clara Bow’s breakout vehicle for good, let’s get one point clear: Wikipedia says that the 1922 picture “was remade by Twentieth Century Fox in 1949,” but — well, that’s Wikipedia for you. (Whoever wrote the article didn’t even know that it’s “20th Century Fox,” not “Twentieth.”) In fact, there is no connection whatsoever between the two pictures — other than the fact that they both deal with whaling ships out of New Bedford, Mass., and they both take their title from Psalm 107:23 (“They that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters…”). These aren’t two versions of the same story, they’re two different movies with the same title; henceforth, when I use the title, I’ll be talking about only one of them.

Music historian Jon Burlingame (in his notes for the movie’s soundtrack CD) says Bartlett’s script underwent a rewrite by John Lee Mahin — shown here (on the left) in a rare acting stint in Hell Below (1933) with Robert Montgomery. Like Bartlett a reporter-turned-screenwriter, Mahin already had a number of major credits on his resume, many of them — including Red Dust, Treasure Island (1934), Test Pilot, Captains Courageous and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1941) — for Hathaway’s mentor Victor Fleming.

Music historian Jon Burlingame (in his notes for the movie’s soundtrack CD) says Bartlett’s script underwent a rewrite by John Lee Mahin — shown here (on the left) in a rare acting stint in Hell Below (1933) with Robert Montgomery. Like Bartlett a reporter-turned-screenwriter, Mahin already had a number of major credits on his resume, many of them — including Red Dust, Treasure Island (1934), Test Pilot, Captains Courageous and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1941) — for Hathaway’s mentor Victor Fleming.Without access to what records might be in the 20th Century Fox archives, it’s impossible for me to say exactly how credit for Down to the Sea‘s script should shake out — which is a pity, because the script is a truly masterful piece of work; if the picture ever gets the kind of attention it has deserved for over 60 years, maybe someone will shed some light on the subject. The writing credit on screen reads “Screen Play by John Lee Mahin and Sy Bartlett; From a Story by Sy Bartlett,” which matches the general drift of the two writers’ careers: story was Bartlett’s long suit, dialogue Mahin’s. Making an educated guess, I’d say Bartlett was responsible for Down to the Sea‘s distinctive blend of rousing adventure and psychological acuity, Mahin for the unerring cadence and vocabulary of the speech of 19th century New England whalermen. Or it may have been more complicated than that; Mahin gets top billing on screen, which suggests that his rewrite probably amounted to more than just touching up the dialogue.

Unfortunately, the decision may be taken out of both their hands. The whaling firm’s insurance company refuses to cover Capt. Joy; moreover, Massachusetts law will not allow Jed to return to sea unless he can pass an exam covering the four years of schooling he missed while he was away. Fortunately, a sympathetic school superintendent (Gene Lockhart, in a warmhearted cameo) fudges Jed’s test results rather than disappoint the captain.

For his part, Dan Lunceford doesn’t care much for the look of Capt. Joy, nor for his sneering at Lunceford’s “book-learnin'” and his college degree in marine biology; only a sweetening of his percentage of the voyage’s profits persuades the younger man to ship out with Capt. Joy after all.

Once the Pride of New Bedford is out to sea, Capt. Joy plays his trump card. He tells Lunceford that he sees “the hand of Providence” in Lunceford’s presence on board. Jed was allowed to ship out, he says, only on the condition that his studies be continued, and Capt. Joy is hereby assigning Lunceford, in addition to his regular duties as first mate, to be Jed’s tutor during his off-duty hours. In this way, the crafty old mariner intends to kill two birds with one stone: he’ll see to Jed’s education, and he’ll keep Lunceford too busy to undermine his authority.

Lunceford has no choice but to accept the assignment, but he does so with ill grace. Resentful at what he regards as essentially a babysitting chore, he is impatient, sarcastic and dismissive. Resentful in turn, Jed is obstreperous and uncooperative. Lunceford decides Jed is just as ornery and pigheaded as his grandfather, and he give up the lessons as a waste of his time.

Stung, Jed applies himself and in time surprises Lunceford with answers to all the questions that had stumped him before. Lunceford suddenly approaches his duties as tutor in earnest, tailoring lessons more carefully to Jed’s quick and lively but unsophisticated intelligence. As the friendship grows between Jed and Lunceford, Capt. Joy begins — rightly or wrongly — to fear that his grandson’s respect and affection are drifting away from himself and attaching themselves to Lunceford; he responds to the unexpected competition by looking more carefully at Lunceford’s ideas, which he had formerly dismissed as not worth his attention. All this happens even as the Pride of New Bedford roams the waters of the South Atlantic, stalking and taking whales.

That’s about as much of the plot as I care to go into here; better that you should discover the rest for yourself. Down to the Sea in Ships isn’t available on home video*, but it does surface (pun intended) from time to time on the Fox Movie Channel, and it’s worth seeking out to discover how the three-generation, three-way relationship of Capt. Joy, Jed and Dan Lunceford plays itself out against the background of a perilous voyage contending with the forces of nature and the leviathans of the deep. Each of the three discovers qualities of strength and character in the others that he either never suspected or did not properly value at first. Each brings out the best in the other two, and allows the other two to bring out the best in him.

…with the crew desperately struggling to free themselves and repair the damage before the sea pounds their ship to splinters against the unforgiving ice. Not to mince words, it’s an absolutely brilliant action/suspense set piece. Amazingly enough, it was shot entirely in a soundstage tank on the Fox lot, but it’s spectacularly convincing and harrowing for all that.

Is this callousness or tough love? Po-tay-to, po-tah-to. Hathaway had a reputation for being tough on actors. His side of it was simply that he refused to mollycoddle them; he expected actors to report to the set ready to work. He also remembered the day they finished shooting Barrymore’s scenes:

“We finish the picture, he walked off the set. No wheelchair. No crutches. And he came to me and said, “Mr. Hathaway, I want to tell you, you did more for me and for my life on this picture than ever happened to me before. From my father or my mother, or from anybody. I was just simply sitting there and waiting to die.”

Hathaway went on to say that they remained friends for the rest of Barrymore’s life. In any case, whatever the validity of Hathaway’s recollection, the evidence is there on screen: Barrymore responded — whether out of spite or chagrin — by giving one of his strongest performances in years. For once he’s not merely being wheeled around the set acting crusty (although in his more physically active shots he was often doubled by assistant director Richard Talmadge).

I don’t mean to minimize the genuine pain Barrymore surely suffered, but that wheelchair must have been a real convenience for a man who had never been all that crazy about being an actor to begin with. In youth, his real interests were in painting, writing, and composing music, but the pressure to enter the family trade (and the money to be made from it) kept him on stage, screen and radio for nearly sixty years. The role of Capt. Bering Joy was a recognizable “Lionel Barrymore type”, but it was also a complex and vigorous character betrayed by age and ill health, and Barrymore the self-described ham connected with it on a more profound level than almost any part he ever played. He deserves to be remembered for this performance as much as — indeed, more than — for the unalloyed wickedness of Henry Potter.

Down to the Sea in Ships was Richard Widmark’s fifth movie, after his sensational debut as the giggling psycho killer Tommy Udo in Hathaway’s Kiss of Death (1947). In the intervening three pictures, Widmark played a woman-beating gang lord (The Street with No Name), a murderously jealous bar owner (Road House) and an underhanded western outlaw (Yellow Sky). The studio realized he was in danger of being typecast as a succession of nutjobs, sleazeballs and unsavories (because he played them so well), when what the studio really needed was another leading man. Casting him as Dan Lunceford was a conscious effort to help him segue into more sympathetic roles. It worked. Widmark went on to be one of Fox’s most stalwart leading men, playing good guys (Slattery’s Hurricane, Panic in the Streets), bad guys (No Way Out, O. Henry’s Full House) and guys in between (Pickup on South Street, Don’t Bother to Knock) — until, like many other stars, he went free-agent in the mid-1950s.

In Down to the Sea, Widmark is top-billed, although he doesn’t appear until half an hour in. His Dan Lunceford is the character who goes through the most self-surprising changes in the course of the picture. After all, Jed is an adolescent coming of age, and changes are to be expected, while Capt. Joy, though seemingly set in his ways and defiantly so, proves to be flexible, open to change, and willing to learn — when he thinks nobody is watching and he can do it without losing face.

Capt. Joy blusters, but it’s Dan Lunceford who is most nearly arrogant at the outset; part of the reason the captain scoffs at Lunceford’s education is that he senses Lunceford is more than a little puffed-up about it. For his part, Lunceford treats Capt. Joy with an exaggerated politeness that stops just short of insolent sarcasm. (Capt. Joy: “You may have noticed that most of my crew generally sign on again.” Lunceford [drily]: “Out of affection no doubt, sir.”) His sarcasm towards Jed’s lessons, on the other hand, is undisguised — at first. In time, he comes to realize he has misjudged them both, especially the captain. By the end he’s telling Jed that his grandfather is “more of a man than you or I could ever hope to be.” It’s an admission Lunceford could hardly have imagined making when the voyage began.

If you ever get the chance to see Down to the Sea in Ships, don’t pass it up. I’ve never shown it to anyone who didn’t love it. I guarantee it: this is one of the greatest movies you never heard of.

_______________

*UPDATE 11/4/2021: Down to the Sea in Ships is now available on DVD from 20th Century Fox Cinema Archives; it’s available here from Amazon.

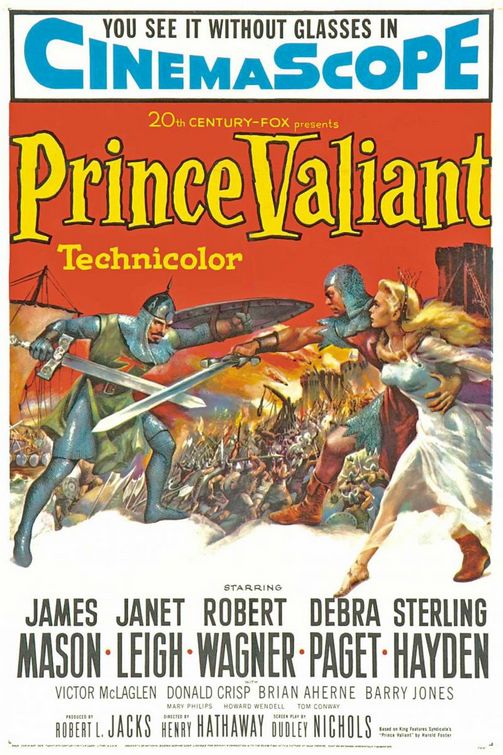

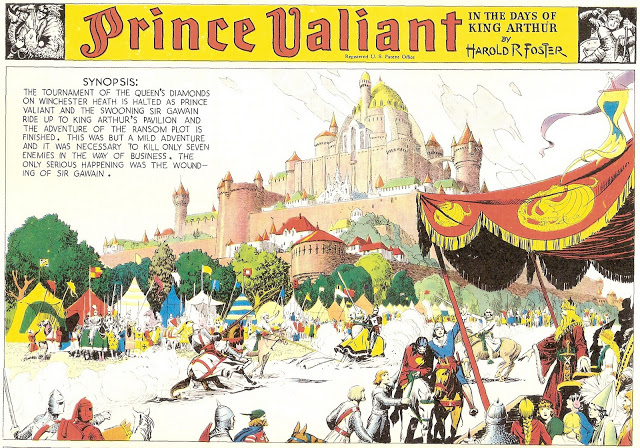

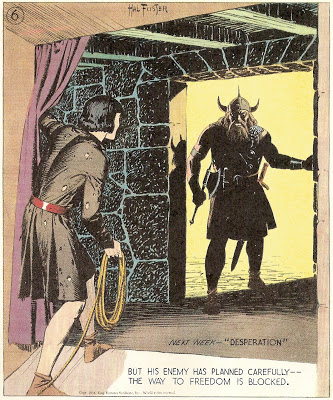

Films of Henry Hathaway: Prince Valiant

Wagner said that mainly, it was the wig (in fact, that’s the title of the chapter in which he discusses it), and as you can see from the picture above, he has a point. Pauline Kael once said that no actor can triumph over a bad toupee; she was talking about Walter Matthau in The Laughing Policeman, but she might well have been thinking of Robert Wagner in Prince Valiant. Wagner claims that Dean Martin visited the set one day and spent ten minutes talking to him before he realized he wasn’t Jane Wyman. Wagner himself thought the wig made him look like Louise Brooks; to me he looks more like Archie’s girlfriend Veronica. In any case, the wig is a performance-killer, no error. I doubt if Richard Burton — another young actor under contract to 20th Century Fox at the time, and one who might have made a good Valiant himself — could have made it work.

But Wagner can’t hang it all on the wig. Whatever his tonsorial accoutrement, his callow performance is more fitting to a Malibu beach boy than a Viking prince. There’s no dialogue coach credited on Prince Valiant; maybe the picture didn’t have one. But somebody should have pointed out to young RJ that the first name of Uther Pendragon is not pronounced “Youther”; nor “betrothed”, “betrawthed”; nor “Gawain”, “Gwayne”. And somebody should have ironed the California twang out of line readings like “Aw, c’mon, don’t be shy.”

It must be said that in every case, that somebody should have been Henry Hathaway.

Wagner’s rise at 20th Century Fox hadn’t exactly been meteoric, but it had been pretty swift: eleven pictures in just over three years. He was earnest and hardworking, but not a natural for a role like this; he had neither the effortless panache of Errol Flynn nor the graceful aplomb of Tyrone Power. He was certainly nowhere near the seasoned performer he would become in time (and remains today). But you can’t say he wasn’t game; thrust by Darryl F. Zanuck into the title role of a comic strip he’d loved as a kid, he dove into it with all the relish his then-limited resources could command. It was a mercy (to him then, to us now) that he didn’t overhear the wisecracks of the crew until his work on the picture was done, so his enthusiasm at least remains high on screen and never flags. An actor, when he’s lucky, gets his in-over-his-head performances out of the way in high school, college or amateur theater, then leaves them behind. It’s Wagner’s bad luck that he had to stumble like this in full view of the world. In CinemaScope and Technicolor.

So let us stipulate that Prince Valiant is mushy at the center, and grant that it’s not easy to watch without wincing in sympathy for a young hero who seems to be floundering in Daddy’s oversize suit of chain mail. The picture still has its pleasures, especially for those who discover it in uncritical childhood — the age at which a couple of generations of kids discovered Harold Foster’s comic strip.

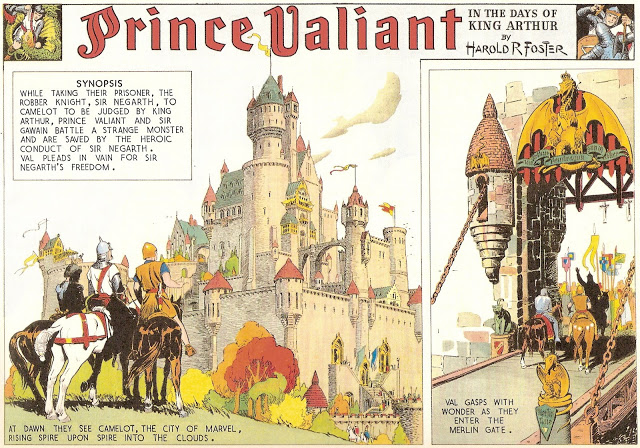

There is, for example, an honorable — and largely successful — effort to duplicate Foster’s richly detailed visual style. Compare this illustration of Foster’s from the first year (1937) of the strip, as Sir Gawain and Valiant approach King Arthur’s Camelot…

…and another of the knights’ colorful pavilions:

In Prince Valiant‘s last half-hour Hathaway — and even Wagner — rise to the occasion, and the picture becomes all a bloodthirsty young fan of the comic strip could wish for. First there’s a hell-for-leather battle between the forces of Valiant’s father King Aguar (Donald Crisp) and those of the usurper Sligon (Primo Carnera), with work by stunt coordinator Richard Talmadge that’s still remarkable to see:

Remember, this was in the days before computer-generated images, and if you wanted fire in your battle scene there was nothing for it but to light the flames…

…and Franz Waxman’s virile, heroic score (one of his best) coming in at exactly the right moment, as Prince Valiant’s magical Singing Sword takes up its song on the side of right and honor. It’s 2 minutes 52 seconds from the first stroke until the villain falls dead, and it’s one of the most exhilarating swordfights ever committed to film.

Reviews for Prince Valiant weren’t particularly generous, but the reviews and Robert Wagner’s wig notwithstanding, the picture did well at the box office. (Wagner, for his part, counted his blessings and resolved never to get stuck in a role like that again.) Of the movies I’ve covered so far in my retrospective posts on Henry Hathaway, this is admittedly the least of them. It’s not historically important like The Trail of the Lonesome Pine, nor a neglected masterpiece like Down to the Sea in Ships, but it’s unpretentious fun in a Boy’s Own Adventure way. Harold Foster’s strip was 16 years old when the picture went into production (it still runs every Sunday in about 300 papers, 74 years after Foster, who died in 1982, created it), so the first generation of Valiant’s fans had kids of their own to take to see the movie.

I’ll let Harold Foster himself have the last word on the picture, from an interview he gave in 1969. It had been 15 years since the movie’s release, and there was no reason for him not to be honest about it. His appraisal of the CinemaScope version of his brainchild was clear-eyed and evenhanded:

“It was a magnificent film — the scenery, the castles, everything was beautiful. They used all my research: Sir Gawain had the right emblem on his shield, everything was right. But somehow, the story was a little bit childish…it was Hollywood.

“I thought [Robert] Wagner was a little bit immature — his face was immature, he ran around with his mouth open. But all in all I got a kick out of it; it was quite an experience.”

Films of Henry Hathaway: Brigham Young (1940)

Mary Astor was an actress of remarkable versatility, which she demonstrated time and again in the course of her 43-year screen career. That point is amply illustrated by this image for the blogathon, since nothing could be more different from the Mary Astor you see here than the one you’ll see in the movie I’ve chosen for the subject of this post…

* * *

“Darryl,” Henry Hathaway said when Darryl F. Zanuck borrowed him from Paramount to direct Brigham Young, “the two dullest things in the whole world are a wagon train and religion. Now you take them and put them together.”

“This man Brigham Young,” Zanuck replied, “is more important than the story.”

Zanuck first became interested in filming the story of the “Mormon Moses” in 1938, at the suggestion of 20th Century Fox staff writer Eleanor Harris and with the encouragement of novelist Louis Bromfield, whom Zanuck hired to write a screen story for another Fox staffer, Lamar Trotti, to turn into a script.

(A side note on Louis Bromfield: In 1940 he was one of the most famous writers in America, considered the peer of Faulkner, Hemingway and Fitzgerald; notice that he receives authorial pride of place on the title card for Brigham Young, in type even larger than that for Zanuck himself. Nearly all of his 30-plus books were bestsellers, and he won a 1927 Pulitzer Prize for his third novel, Early Autumn. In his day he was a prime example of the Literary Man as Celebrity: Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall were married at his Ohio farm in 1945. Alas, when he died in 1956 it was almost as if every one of his readers had died with him, and he is largely — and unfairly — forgotten today. A number of his books were made into memorable movies, and I may be posting on some of them in time to come.)

Although the title of the picture was Brigham Young, top billing went to Tyrone Power and Linda Darnell as two fictitious characters created by Bromfield and Trotti. Power was cast as Jonathan Kent, a young non-Mormon “outsider” who ends up scouting for Brigham Young and his followers on their trek west, while Darnell was to play Zina Webb, a Mormon girl with whom he falls in love.

Originally slated to direct Brigham Young was Fox contract director Henry King, the studio’s specialist in historical pictures and atmospheric Americana. King had already directed such Fox pictures as State Fair (1933), Ramona and Lloyds of London (both ’36), In Old Chicago (’37), Alexander’s Ragtime Band (’38), and Jesse James and Stanley and Livingstone (both ’39). (Several of those had starred Tyrone Power, although Power had yet to be cast in Brigham Young.) It seemed a natural fit, but for some reason the deal with King fell through. James D’Arc, in his commentary on the Brigham Young DVD, says that he could find no documentation in the Fox archives explaining this. I think it’s just possible — and I hasten to emphasize that this is the purest speculation on my part — that King, a Catholic, was uncomfortable with the Mormon story. I have absolutely no evidence for this, but it strikes me as the sort of thing that wouldn’t necessarily be committed to paper.

In any case, whatever the reason, in January 1940 Zanuck arranged to borrow Henry Hathaway from Paramount to direct the picture. That was when Hathaway made the remark that opens this post; it was also when Hathaway suggested changing the religious orientation of the two star characters: make Jonathan Kent the Mormon and Zina Webb the outsider. Zanuck agreed, and Hathaway (at his own expense) brought in Grover Jones, who had worked with him on Lives of a Bengal Lancer (’35) and The Trail of the Lonesome Pine (’36), among others, to write the change into the script. (Lamar Trotti, Hathaway later said, was incensed, and didn’t speak to the director for the rest of his life.)

In the movie, Joseph Smith is tried and convicted of treason. The trial is fictional; actually, Smith was awaiting trial when he was murdered. But it dramatizes the rabid anti-Mormon sentiment of the time in the raving denunciations of the prosecutor (Marc Lawrence) and the unhesitating “guilty” verdict of the jury. It also allows Brigham Young to address the court, describing his first meeting with Joseph Smith (shown in flashback) and delivering a ringing endorsement of freedom of religion: “You can’t convict Joseph Smith just because he happens to believe something you don’t believe. You can’t go against everything your ancestors fought and died for. And if you do, your names, not Joseph Smith’s, will go down in history as traitors. They’ll stink in the records, and be a shameful thing on the tongues of your children.” (In fact, during the events that led up to Smith’s killing, Young was in Massachusetts spreading the word and recruiting converts.) After the trial, a resigned Smith implicitly transfers care of his flock to Young — “I want you to stay and take care of my people.” — before being led off with his brother Hyrum (Stanley Andrews, the “Old Ranger” of TV’s Death Valley Days). Later, the mob murder of Hyrum and Joseph is shown pretty much as it happened that night in Carthage, Ill.

In the movie, Joseph Smith is tried and convicted of treason. The trial is fictional; actually, Smith was awaiting trial when he was murdered. But it dramatizes the rabid anti-Mormon sentiment of the time in the raving denunciations of the prosecutor (Marc Lawrence) and the unhesitating “guilty” verdict of the jury. It also allows Brigham Young to address the court, describing his first meeting with Joseph Smith (shown in flashback) and delivering a ringing endorsement of freedom of religion: “You can’t convict Joseph Smith just because he happens to believe something you don’t believe. You can’t go against everything your ancestors fought and died for. And if you do, your names, not Joseph Smith’s, will go down in history as traitors. They’ll stink in the records, and be a shameful thing on the tongues of your children.” (In fact, during the events that led up to Smith’s killing, Young was in Massachusetts spreading the word and recruiting converts.) After the trial, a resigned Smith implicitly transfers care of his flock to Young — “I want you to stay and take care of my people.” — before being led off with his brother Hyrum (Stanley Andrews, the “Old Ranger” of TV’s Death Valley Days). Later, the mob murder of Hyrum and Joseph is shown pretty much as it happened that night in Carthage, Ill.

The climax of Brigham Young comes, not surprisingly, in the spring of 1848. After a grueling and disastrous winter of 1847-48, when the Mormon settlement in the Great Salt Lake Valley faced starvation that threatened to decimate their numbers — if not annihilate them entirely — things are beginning to look up with the spring planting. Then, a new disaster. A sudden infestation of crickets arrives to wipe out their crops. This scene was shot in Elko, Nev., where just such an invasion (at the time, anyhow) occurred like clockwork every few years. Hathaway and the company flew to Elko and waited. Just as they were getting impatient — “Don’t they know they’re holding up the schedule?” — the crickets arrived, and it was a nightmare as much for the company as it had been for the Mormons in 1848. Mary Astor left vivid descriptions in both her volumes of memoirs: the ugly bugs, countless millions of them, the size of her thumb, the piles of them as much as a foot high, the stench as they died and rotted in the 110-degree heat. The scene was scheduled to be shot over four days, but after one horrible day the cast and crew were in revolt; the hell with the money, they were going home. Hathaway and Grover Jones put their heads together, combining, shifting, telescoping. Finally Hathaway assembled the company, promising to wrap things by noon the next day if everybody would knuckle down and go to it. They didn’t make noon, but by four p.m., with heroic efforts, they were done.

In the movie, just as the Mormon despair matches that of their 1940 portrayers, comes…

…the famous Miracle of the Seagulls, a sky-blotting flight of birds that, in the words of one Mormon of the 1840s, came “sweep[ing] the crickets as they go”, devouring the insects and saving the settlers’ crops.

Again, some dramatic license here. Where in history the cricket invasion had descended on the settlement for several days, to be followed by two weeks of the saving intervention of the seagulls, the movie has the whole thing, crickets and seagulls both, occurring on the same frantic day, set to the stirring strains of Alfred Newman’s epic score. (In a nicely subliminal touch, the theme Newman used to score the arrival of the crickets was a variation on the music he used to accompany the nightrider raid on the Kent homestead at the opening of the picture.)

The scene of the seagulls, like this shot here, is another example of Fred Sersen’s work, combining images of the company on location at Lone Pine, Cal., with footage of seagulls shot months earlier at Utah Lake near Provo.

And finally, it must be said that in point of historical fact, Brigham Young wasn’t there for the Miracle of the Seagulls; he was off to the east arranging for the safe passage of later Mormon settlers, and he only heard of his followers’ miraculous deliverance by letter from his deputies on the scene. For a movie, of course, this would never do; Dean Jagger’s Brigham — along with Mary Ann, and Jonathan and Zina, and even the ankle-biting Angus Duncan — had to be on hand, right there in what would one day be Salt Lake City, Utah, reveling in the divine vindication of Brigham Young’s leadership, which had brought him and his followers across a thousand miles of hostile prairie to their Promised Land.

Films of Henry Hathaway: Fourteen Hours (1951)

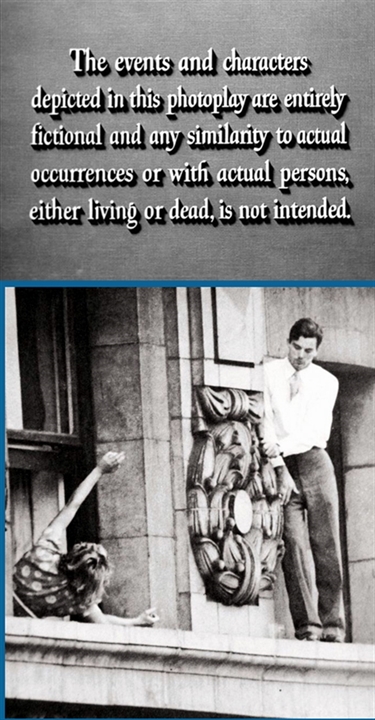

This title card appears early in Henry Hathaway’s Fourteen Hours — at the “climax” of the opening credits, you might say, just before the credit cards for producer Sol C. Siegel and director Hathaway. It’s the standard “entirely fictional and any similarity” disclaimer, the kind that usually appears in super-small type somewhere near the copyright notice, the MPAA “approved” certificate number, the Western Electric and IATSE credits, and other things that are legally required but nobody really cares if you see or not. For this picture, though, 20th Century Fox took the unusual step of making sure the disclaimer was very prominently placed where even the most inattentive could hardly miss it.

This title card appears early in Henry Hathaway’s Fourteen Hours — at the “climax” of the opening credits, you might say, just before the credit cards for producer Sol C. Siegel and director Hathaway. It’s the standard “entirely fictional and any similarity” disclaimer, the kind that usually appears in super-small type somewhere near the copyright notice, the MPAA “approved” certificate number, the Western Electric and IATSE credits, and other things that are legally required but nobody really cares if you see or not. For this picture, though, 20th Century Fox took the unusual step of making sure the disclaimer was very prominently placed where even the most inattentive could hardly miss it.

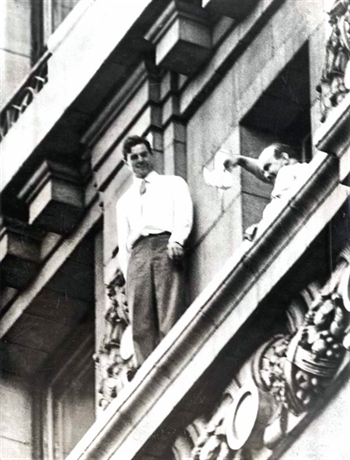

The studio didst protest too much; the disclaimer was disingenuous. Fourteen Hours was generally fictional, but not entirely, and its similarity to “actual occurrences” and “actual persons” was fully intended.

Here’s Exhibit A. This isn’t a still from the movie, it’s a news photo from real life, taken on Tuesday, July 26, 1938. The man is 26-year-old John William Warde; the woman is his sister Katherine, 22. On that day, John and Katherine were visiting friends, a Mr. and Mrs. Valentine, who lived in Room 1714 of New York’s Gotham Hotel. Sometime around 10:30 in the morning, after John, Katherine and Mrs. Valentine had ordered lunch from Room Service, John calmly announced, “I’m going out the window.” And as the two women stared dumbfounded, he did. In a panic, Katherine phoned the front desk, screaming that her brother had jumped out the window — but he had only clambered out onto the ledge. And there he stayed while a crowd of spectators gathered in the street 170 feet below, traffic came to a standstill, and police emergency crews scrambled to coax, cajole or drag him to safety. Hoping to talk him in, NYPD traffic cop Charles Glasco chatted with Warde disguised as a hotel bellhop (Warde had threatened to jump if any cop came near him). Warde, who had attempted suicide before and been diagnosed with “manic-depressive psychosis” (that era’s term for bipolar disorder), resisted every effort. “I’ve got to work things out for myself,” he kept saying, “I’ve got problems to think about.”

That, in a nutshell, is the story of that day in 1938, and it’s also the premise of Fourteen Hours. This lobby card even eerily mirrors the photo — although the characters here aren’t brother and sister, they’re Robert Cosick (Richard Basehart) and Virginia Foster (Barbara Bel Geddes), his ex-fiancée. The movie’s disclaimer is further belied by its writing credit: “Screen Play by John Paxton From a Story by Joel Sayre”. The “story” was an article by Sayre, “That Was New York: The Man on the Ledge”, which appeared in The New Yorker on April 16, 1949, chronicling John Warde’s story. And the picture’s original working title was The Man on the Ledge, just like Sayre’s factual article. (As for why the title was changed, I’ll get to that later.)

So much for those supposedly not-intended similarities; some of them, anyhow. It’s the differences between real life and the movie that make Fourteen Hours so interesting.

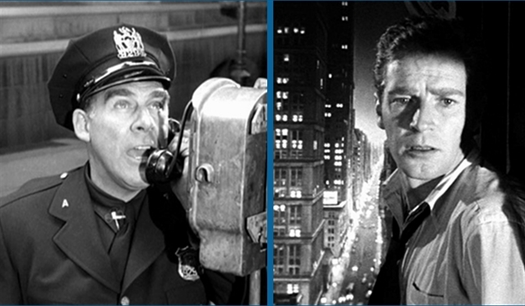

The picture opens quietly — in silence, in fact, without dialogue or even background music. (Indeed, except for Alfred Newman’s fervid theme under the opening credits, then a second theme swelling through the movie’s last 90 seconds, there’s no music in the entire picture.) We are introduced to what will prove to be the two central characters in the drama that follows. First we see Patrolman Charlie Dunnigan (Paul Douglas as the movie’s version of Charles Glasco) walking his beat in the early morning calm. He passes the Rodney Hotel, where a worker is polishing the brass plate at the entrance. Meanwhile, up in Room 1505…

The picture opens quietly — in silence, in fact, without dialogue or even background music. (Indeed, except for Alfred Newman’s fervid theme under the opening credits, then a second theme swelling through the movie’s last 90 seconds, there’s no music in the entire picture.) We are introduced to what will prove to be the two central characters in the drama that follows. First we see Patrolman Charlie Dunnigan (Paul Douglas as the movie’s version of Charles Glasco) walking his beat in the early morning calm. He passes the Rodney Hotel, where a worker is polishing the brass plate at the entrance. Meanwhile, up in Room 1505…

…a room service waiter (Frank Faylen) is delivering a breakfast tray to a guest registered as William E. Cook of Philadelphia, but who is really Robert Cosick (Basehart). He hands the waiter some cash, and the waiter turns his back to count out his change on a tray. When he turns back, the room is empty. He checks the closet, then the bathroom. He notices the curtains billowing at the open window. Glancing out, he sees the missing guest standing on the ledge, breathing heavily, looking agitated.

Then the silence is rudely broken by the first human sound we hear — a secretary screaming in the window of a bank building across the street. Dunnigan dashes into the hotel to alert the staff, while the waiter calls down to the switchboard for the same reason. Dunnigan and Harris, the assistant manager (Willard Waterman), knowing now which room to go to, head up in the elevator. In the room, Harris blusters at Robert to come inside, sounding like an impotent scold.

Then the silence is rudely broken by the first human sound we hear — a secretary screaming in the window of a bank building across the street. Dunnigan dashes into the hotel to alert the staff, while the waiter calls down to the switchboard for the same reason. Dunnigan and Harris, the assistant manager (Willard Waterman), knowing now which room to go to, head up in the elevator. In the room, Harris blusters at Robert to come inside, sounding like an impotent scold.

Down in the street, pedestrians are beginning to gather. The first two we see idly wonder if this is some kind of advertising stunt. Patrol cars screech to a halt at the hotel entrance, sirens blaring. Up in 1505, Robert warns Harris that if a cop comes near him, he’ll jump. Hearing that, Dunnigan commandeers Harris’s necktie to disguise his own uniform, then sits on the window sill, trying to strike up a conversation with the distraught Robert.

The colloquy between Charlie Dunnigan and Robert Cosick, a mixture of urgent pleading and forced-casual chitchat, provides the spine of Fourteen Hours, just as the real one between Charles Glasco and John Warde did for Joel Sayre’s New Yorker article. (Notice too how Joe MacDonald’s deep-focus photography emphasizes both men’s perilous perch 15 stories up. MacDonald was a master cinematographer who worked with Hathaway on nine pictures, including some of his best.)

The colloquy between Charlie Dunnigan and Robert Cosick, a mixture of urgent pleading and forced-casual chitchat, provides the spine of Fourteen Hours, just as the real one between Charles Glasco and John Warde did for Joel Sayre’s New Yorker article. (Notice too how Joe MacDonald’s deep-focus photography emphasizes both men’s perilous perch 15 stories up. MacDonald was a master cinematographer who worked with Hathaway on nine pictures, including some of his best.)

Over this bare factual skeleton Paxton’s script skillfully weaves a variety of fictional stories among the people drawn for one reason or another to the Rodney Hotel and the street outside. It amounts to a cross-section of the New York public circa 1950 — and for all the changes the city has seen in 69 years, it still rings true today.

Over this bare factual skeleton Paxton’s script skillfully weaves a variety of fictional stories among the people drawn for one reason or another to the Rodney Hotel and the street outside. It amounts to a cross-section of the New York public circa 1950 — and for all the changes the city has seen in 69 years, it still rings true today.

Caught in the traffic jam down in the street are several cab drivers, unable to move their vehicles and looking at a day with no fares. “If I had my M-2 I could knock him off from here, clean,” says one of them (Harvey Lembeck). (And by the way, the African American gentleman is the great Ossie Davis, at the very beginning of his long career.) Another cabbie grumbles that if the guy wants to jump he should go ahead so the rest of New York can get on with their business. “Who cares? I figured on a good day today.”

Later on, this same sour cabbie suggests they should all pony up a buck for a pool and pick an hour; “the guy that gets closest to the time this joker jumps, that guy wins the pot.” His fellows are uneasy at his ghoulish idea, but they all go along.

Elsewhere in the crowd the reaction is more compassionate. Two young office workers, Ruth (Debra Paget, left) and Barbara (Joyce Van Patten, right), have gotten sidetracked on their way to work. The fretful Barbara wants only to get to work before they get in trouble with the boss. But Ruth is more worried about the stranger on the fifteenth floor: How old is he? What kind of trouble is he in? “Maybe someone was cruel to him, or maybe he’s just lonely…I wish I could help him.” Her tender words catch the ear of Danny behind her (Jeffrey Hunter), also pausing on his way to work. When Barbara gives up and leaves, Danny and Ruth strike up a sweetly tentative conversation. As the day wears on, neither of them will get to work. Feelings grow between them, and Danny reflects on how they might have gone their whole lives, missing each other by minutes, if it hadn’t been for this day. Hunter and the 17-year-old Paget were already launched on their successful careers as Fox contract players. Van Patten, making her film debut at 16, would in time become one of television’s busiest character actresses in a career that is still going strong today.

Elsewhere in the crowd the reaction is more compassionate. Two young office workers, Ruth (Debra Paget, left) and Barbara (Joyce Van Patten, right), have gotten sidetracked on their way to work. The fretful Barbara wants only to get to work before they get in trouble with the boss. But Ruth is more worried about the stranger on the fifteenth floor: How old is he? What kind of trouble is he in? “Maybe someone was cruel to him, or maybe he’s just lonely…I wish I could help him.” Her tender words catch the ear of Danny behind her (Jeffrey Hunter), also pausing on his way to work. When Barbara gives up and leaves, Danny and Ruth strike up a sweetly tentative conversation. As the day wears on, neither of them will get to work. Feelings grow between them, and Danny reflects on how they might have gone their whole lives, missing each other by minutes, if it hadn’t been for this day. Hunter and the 17-year-old Paget were already launched on their successful careers as Fox contract players. Van Patten, making her film debut at 16, would in time become one of television’s busiest character actresses in a career that is still going strong today.

Needless to say, New York’s newshounds are also Johnny-on-the-spot. Newspapermen swarm over the scene like ants on a sugar cube. New York announcer George Putnam, playing himself, gives a play-by-play summary from a radio truck in the street. Another radio reporter barges into Room 1505 to jam a microphone out the window to eavesdrop on Dunnigan and Robert’s conversation — only to get the bum’s rush from the vigilant police. Station WNBC dispatches a television camera crew to the roof of a building across the street from the hotel. (Curiously enough, this wasn’t just an embellishment in Paxton’s script. NBC really did broadcast TV coverage of John Warde’s exploit back in 1938, even though there probably weren’t more than a few dozen sets in the whole city, and practically none in the rest of the country. It may well have been the very first example of television covering a breaking news story.)

Needless to say, New York’s newshounds are also Johnny-on-the-spot. Newspapermen swarm over the scene like ants on a sugar cube. New York announcer George Putnam, playing himself, gives a play-by-play summary from a radio truck in the street. Another radio reporter barges into Room 1505 to jam a microphone out the window to eavesdrop on Dunnigan and Robert’s conversation — only to get the bum’s rush from the vigilant police. Station WNBC dispatches a television camera crew to the roof of a building across the street from the hotel. (Curiously enough, this wasn’t just an embellishment in Paxton’s script. NBC really did broadcast TV coverage of John Warde’s exploit back in 1938, even though there probably weren’t more than a few dozen sets in the whole city, and practically none in the rest of the country. It may well have been the very first example of television covering a breaking news story.)

Also making her film debut in Fourteen Hours was 21-year-old Grace Kelly, playing Louise Ann Fuller, on her way to discuss a divorce settlement with her estranged husband (James Warren) and their lawyers in an office overlooking the ongoing crisis. As the legal beagles drone on about the division of community property, Mrs. Fuller is preoccupied with the drama outside the office window; it begins to dawn on her that her own marital problems might not be so irreconcilable after all.

Kelly’s performance here led directly to landing her star-making role in High Noon the following year, but the casting became a bone of contention between Hathaway and Darryl F. Zanuck. Hathaway tested two women for the role, and he wanted Kelly. But Zanuck held out for the other woman — Anne Bancroft, who had just been signed to a Fox contract. As Hathaway acknowledged years later, they were both right, though Bancroft was only 19 and her talent wouldn’t reach full bloom for another ten years. Still, it’s intriguing to imagine how differently the two women’s careers might have gone if Zanuck had won that particular standoff.

While the crowd in the street mills about gawking, wringing their hands, or cracking callous jokes, up on the fifteenth floor things are in a muffled uproar. The NYPD’s rescue efforts are commanded by the officious but efficient Deputy Chief Moksar (Howard Da Silva, left), who coordinates activities while straight-arming a swarm of reporters and dealing with other interfering looky-loos (at one excruciatingly delicate moment, a crackpot preacher bursts into the room bellowing at Robert to kneel and pray). Police psychiatrist Dr. Strauss (Martin Gabel, center) offers on-the-fly advice to Moksar and Dunnigan on Robert’s mental state. Further complications come with the arrival of Robert’s divorced parents — his clutching, hysterical mother (Agnes Moorehead, second right) and feckless alcoholic father (Robert Keith, right), who graphically illustrate the Cosick family dysfunction. (“No wonder he’s cuckoo!” growls Moksar.)

While the crowd in the street mills about gawking, wringing their hands, or cracking callous jokes, up on the fifteenth floor things are in a muffled uproar. The NYPD’s rescue efforts are commanded by the officious but efficient Deputy Chief Moksar (Howard Da Silva, left), who coordinates activities while straight-arming a swarm of reporters and dealing with other interfering looky-loos (at one excruciatingly delicate moment, a crackpot preacher bursts into the room bellowing at Robert to kneel and pray). Police psychiatrist Dr. Strauss (Martin Gabel, center) offers on-the-fly advice to Moksar and Dunnigan on Robert’s mental state. Further complications come with the arrival of Robert’s divorced parents — his clutching, hysterical mother (Agnes Moorehead, second right) and feckless alcoholic father (Robert Keith, right), who graphically illustrate the Cosick family dysfunction. (“No wonder he’s cuckoo!” growls Moksar.)

The last puzzle piece slips into place with the arrival of Virginia Foster (Barbara Bel Geddes), Robert’s ex-fiancée. Strauss and Dunnigan take her aside. Why did she break the engagement?, they ask. “I didn’t, he did,” she says. Why? “He just said that he couldn’t…that he’d make me unhappy…”

Dunnigan: “Did you have a fight?”

Virginia: “No, but he’d get mad…”

Strauss: “What about?”

Virginia: “Whenever I tried to help him…”

Strauss launches into a Freudian spiel about how Robert’s mother couldn’t admit, even to herself, that she never wanted him, so she sublimated by teaching Robert to hate his father — which Robert subconsciously knew was wrong, so he only ended up hating himself. It’s a slick piece of 1950s Psych 101 to explain why Robert is out on that ledge.

BUT…That dialogue exchange among Strauss, Dunnigan and Virginia is a classic piece of Breen Office-era code. Adult audiences in 1951 would have had no trouble reading between those lines, imagining exactly what Robert “couldn’t” do that would make Virginia “unhappy”, and with a little more imagination they could picture what Virginia did to “try to help him” that made him so mad. This plants a suggestion, taboo in 1951, that may still go over viewers’ heads today just as it did the Breen Office’s back then, and for the same reason: they’re not accustomed to reading between the lines.

‘Nuff said.