The Last Cinevent, the First Picture Show — Day 3

Apologies for the delay in getting to Day 3. This year is a unique situation: For the first and only time, my coverage of Cinevent has conflicted with the Thanksgiving Holiday Season. What with taking down Halloween decorations, preparing for (and eating) the Big Feast, and beginning decking the halls with Yuletide trimmings, Cinevent just got elbowed aside. This will of course not be an issue when The Columbus Moving Picture Show (CMPS) takes over next Memorial Day. For now, where was I? Oh yeah…

Saturday morning at Cinevent, of course, is Cartoon Time. This year, animation curator Stewart McKissick took advantage of the scheduling anomaly to establish a Halloween theme for the program; most of the cartoons had at least a tenuous connection to something eerie, ghostly, creepy or monstrous; all that was missing was the “Night on Bald Mountain” sequence from Fantasia. Some highlights (I include YouTube links where available):

One of my favorites this year was the first one, I Heard (1933), with Betty Boop (any Betty Boop is likely to be one of my favorites). The Halloween connection was a baseball game among ghosts at the bottom of a coal mine (the “Never Mine”) in the last minute. For the rest, it was Betty in her sex-kitten prime, with the patented Fleischer surrealist funk, set to a jazz score provided by the unjustly forgotten Don Redman and His Orchestra. I couldn’t make room for an I Heard image in this collage, so let’s move on now to the others.

One of my favorites this year was the first one, I Heard (1933), with Betty Boop (any Betty Boop is likely to be one of my favorites). The Halloween connection was a baseball game among ghosts at the bottom of a coal mine (the “Never Mine”) in the last minute. For the rest, it was Betty in her sex-kitten prime, with the patented Fleischer surrealist funk, set to a jazz score provided by the unjustly forgotten Don Redman and His Orchestra. I couldn’t make room for an I Heard image in this collage, so let’s move on now to the others.

Soda Squirt (1933) (top row left) had Ub Iwerks’s Flip the Frog welcoming a succession of movie stars to the Hollywood-premiere-style grand opening of his new soda fountain. These celebrity-caricature cartoons are a sub-genre in their own right (I’m always a sucker for them myself); maybe one of these years (assuming CMPS retains the Saturday animation program) Stewart will schedule a whole program just of these. He’d have plenty to choose from.

In Pluto’s Judgement Day (1935) (top row right), Mickey’s dog’s penchant for tormenting cats comes back to bite him (if you’ll pardon the expression) when he dreams himself into Kitty Hell, where he is put on trial for crimes against the feline species.

Like Duck Dodgers in the 24½th Century (see below), Rocket to Mars (1946) (second row left) was Halloween-by-way-of-science-fiction, with Olive Oyl accidentally launching Popeye and herself into outer space, where they have a close encounter with a Bluto-like alien tyrant bent on interplanetary conquest. Curiously enough, this one was directed by Vladimir “Bill” Tytla, who created the memorable images in the “Night on Bald Mountain” sequence mentioned above.

Frankenstein’s Cat (1942) (second row right) began life as one of producer Paul Terry’s Super Mouse cartoon — but very early in the series’ life, Terry got wind of a Supermouse comic-book, so to prevent confusion (and to avoid free publicity for somebody else’s product) he changed the name to Mighty Mouse. Most extant prints (including the one Cinevent saw and the one at the YouTube link) are from TV prints where “Super” is overdubbed with “Mighty”. Having originated as a Super Mouse, this one is a straight narrative, rather than one of the mini-operas the Mighty Mouse cartoons would later become. Super/Mighty is differently proportioned, too, with a bigger chest and scrawnier limbs than the character we all remember singing, “He-e-e-e-e-e-re I come to save the da-a-a-a-a-a-ay!”

The program culminated in a triple-peak of great pictures from Chuck Jones and Warner Bros., one Looney Toon and two Merrie Melodies. First was Hair-Raising Hare (1946) (third row right), featuring the first appearance of that hulking orange monster who remained unnamed on screen but was later referred to as either Rudolph or Gossamer (“Gossamer”??? I guess that’s like calling a seven-foot basketball player “Stubby”).

Duck Dodgers in the 24½th Century (1953) (bottom row right), besides being Halloween-by-way-of-science-fiction like Rocket to Mars, is simply one of the all-time great cartoons; Stewart could screen it every year until the print disintegrated and I wouldn’t squawk. Like Hair-Raising Hare, there’s no YouTube link for this gem; you’ll just have to spring for Looney Toons Golden Collection (the first volume, hence no number) to get this and a ton of other greats. However, YouTube does have the cartoon with an amusing commentary by two gents (heretofore unknown to me) named Trevor Thompson and Sean McBee. You can access that here.

The only cartoon in this collage that gets two images (bottom left) was (1) the final one on the program and (2) one of my all-time favorites: Claws for Alarm (1954). Motoring through the Southwest, Porky and Sylvester stop for the night in a desert ghost town where Porky, not noticing the lack of inhabitants, blithely signs the cobwebby register at the hotel. The town is inhabited after all, but not by ghosts — instead, the locals are mice posing as ghosts to try to scare off the interlopers. It works on Sylvester, but Porky remains oblivious and refuses to leave. The images here show Sylvester shivering in the night (below), and (above) the departure next morning with Porky singing his hilarious broken-record rendition of “Home on the Range” (you’ll have to see it to get the joke). This one is available whole on YouTube, albeit with — I kid you not — Greek subtitles. But those are easy enough to disregard, so click on over and enjoy. (And by the way, if you’ve ever wondered what “Sylvester” looks like in Greek, it’s “ΣΙλβεστερ”. Never let it be said that Cinedrome neglects a classical education.)

After the animation program, the Saturday kiddie matinee vibe continued, as it has most years — this time with a trio of silent Our Gang shorts from Hal Roach: Dogs of War (1923), Big Business (1924; not to be confused with the 1928 Laurel and Hardy classic), and The Sun Down Limited (1924). All three were directed by the all-but-unsung Robert F. McGowan. If Hal Roach was the Our Gang series’ commanding general, McGowan was his executive officer; he directed or co-directed 102 of the shorts between 1922 and 1936 and played a major role in shaping their comic style while getting natural, unself-conscious performances from the kids. Film history owes Robert McGowan a lot.

After the animation program, the Saturday kiddie matinee vibe continued, as it has most years — this time with a trio of silent Our Gang shorts from Hal Roach: Dogs of War (1923), Big Business (1924; not to be confused with the 1928 Laurel and Hardy classic), and The Sun Down Limited (1924). All three were directed by the all-but-unsung Robert F. McGowan. If Hal Roach was the Our Gang series’ commanding general, McGowan was his executive officer; he directed or co-directed 102 of the shorts between 1922 and 1936 and played a major role in shaping their comic style while getting natural, unself-conscious performances from the kids. Film history owes Robert McGowan a lot.

That said, I must confess I’m never entirely satisfied with the silent Our Gangs. Delightful as they are, I miss the voices, having first encountered and grown up with the talkie shorts on TV in their Little Rascals phase. Darla warbling “I’m in the Mood for Love”, Alfalfa screeching “The Barber of Seville”, Tommy Bond’s Butch muttering “C’mon, Woim”, the wise banter between Spanky McFarland and Scotty Beckett at their cutest — all that is a major component of the shorts’ charm for me. Still, the silent shorts are worth seeing, and not just as historical artifacts.

Then the Kiddie Matinee section of the day wound up with Chapters 7-9 of King of the Texas Rangers, and it was time for lunch.

Back from lunch break, we saw Stella (1950). The lobby card reproduced here is a trifle misleading, as can be seen by perusing my notes for the Cinevent program book:

Back from lunch break, we saw Stella (1950). The lobby card reproduced here is a trifle misleading, as can be seen by perusing my notes for the Cinevent program book:

You won’t find Claude Binyon’s name in any of the high-end film encyclopedias, and maybe that’s as it should be. Still, his career was nothing to sneeze at. Like so many screenwriters of the era, he started out as a newspaperman, working for the Chicago Examiner — then later, as city editor for Variety. Legend has it that in that capacity he concocted the immortal 1929 headline WALL ST. LAYS AN EGG — though it’s only right to mention that other legends credit Sime Silverman and Abel Green.

Whatever Binyon’s experience at the showbiz Bible, by 1932 he had segued from writing about movies to writing for them, with his first job being one of 16 writers on the omnibus comedy If I Had a Million (1932). That was one time when too many cooks didn’t spoil the soup, though it would be nice to know how much of which episode Binyon worked on.

As a contract writer at Paramount throughout the 1930s and into the ’40s, Binyon kept busy; he made uncredited contributions to such pictures as The Old Fashioned Way and It’s a Gift (both 1934), The Princess Comes Across (’37) and Dixie (’43), and he was the writer of record on a whopping 14 pictures for director Wesley Ruggles, including the Bing Crosby/Fred MacMurray/Donald O’Connor vehicle Sing, You Sinners (’38). Later, Binyon gave Der Bingle and Fred Astaire a 24-karat setting in Holiday Inn (’42) — with a major assist, of course, from Irving Berlin’s songs. Then again, Berlin also wrote the songs for the Crosby/Astaire follow-up vehicle Blue Skies (’46), with distinctly inferior results. True, director Mark Sandrich didn’t live to complete Blue Skies as he had Holiday Inn – but Binyon didn’t write Blue Skies either. Coincidence? Maybe.

Anyhow, let’s say it again: A career not to be sneezed at.

Binyon never abandoned writing for other directors, right up through Henry Hathaway’s hilarious North to Alaska (1960) and Leo McCarey’s last two pictures, 1958’s Rally ‘Round the Flag, Boys! and Satan Never Sleeps in 1962. But he started directing his own scripts with The Saxon Charm in 1948, and continued the practice off and on through 1956, with generally happy results. Cinevent50 viewers got a delicious helping of Binyon the auteur with Dreamboat (’52), his delightful satire of Hollywood, academia and TV starring Clifton Webb and Ginger Rogers.

Dreamboat was probably the peak of Binyon’s career as writer-director, but he had come close to it two years earlier with Stella, based on Doris Miles Disney’s novel Family Skeleton. Ms. Disney’s book told the story of the Bevans family, a rather dimwitted clan whose cantankerous Uncle Joe dies accidentally during a family outing. Fearing that nobody will believe they didn’t kill the old reprobate on purpose, his surviving relatives decide to give him a hasty burial in an unmarked grave and pretend he’s just off on one of his benders. The only one not in on this birdbrained scheme is Stella, the family breadwinner and the only one with the sense God gave a goose. By the time she learns what’s happened, it seems there’s nothing to be done but ride the thing out. Then the plot thickens when it comes to light that Uncle Joe was insured for $20,000, and Stella’s layabout brothers-in-law begin conniving to cash in — and thicker still, Stella works as a secretary for Uncle Joe’s insurance agent.

The New York Times appraised Family Skeleton as “half humorous…not a mystery, hardly even a murder novel, and certainly not the light farce suggested by the publisher’s grinning skull symbol.” Which sounds odd now in light of the movie 20th Century Fox and Binyon made of the book, because a light farce is exactly what Binyon delivered, with a mix of black comedy and a New England setting that foreshadowed Hitchcock’s The Trouble with Harry (1955).

The central role of Stella was reportedly first assigned to Fox contract star Susan Hayward. When she turned it down — wisely, since comedy was never Hayward’s strength — the role went to Ann Sheridan, whose droll delivery was certainly better suited to the material. Sheridan also exerted a lightening influence on co-star Victor Mature (who too seldom got to deploy his flair for comedy) as an insurance investigator who smells something fishy. But good as those two are, the movie gets stolen right out from under them by David Wayne and Frank Fontaine (still ten years from his most famous turn as Crazy Guggenheim on The Jackie Gleason Show) as the venal brothers-in-law, and by Evelyn Varden as the family’s whimpering matriarch.

In reviewing Stella for The New York Times, Thomas M. Pryor noted: “Out of an essentially macaber [sic] situation, Claude Binyon…has drawn some of the most unusual comedy of the season.” Variety’s “Brog” concurred that “a missing corpse takes on a comedic flavor with quick pacing and sharp dialog.”

As a side note, Stella marked the final (posthumous) appearance of the prolific character actor Hobart Cavanaugh as the local undertaker. This fact prompted columnist Jimmy Fidler — a week after Cavanaugh’s passing and three months before the movie’s release — to write: “Hobart Cavanaugh, who died the other day, had specialized for years in ‘Mr. Milquetoast’ roles, but I think the cast and crew of ‘Stella,’ his last picture, will always remember him as a man of extraordinary courage. Cavanaugh, who had already submitted to one operation for intestinal cancer, came to work on that picture in a dying condition, well aware of the fact that he didn’t have more than one chance in a million to live another month. He hadn’t been able to eat a bite of food for five days, and he was unable to eat during the several days it took him to complete his role. Twice he collapsed on the set, but he insisted on finishing the job. And when he had done so he said his goodbyes with a wisecrack thrown in for seasoning. ‘I play an undertaker in this picture but it’s poor casting,’ he laughed. ‘I look more like the corpse.’ It takes fortitude for a man to make remarks like that while facing another operation that is almost sure to be fatal.” This blurb has all the earmarks of an item planted by the Fox publicity department to wring some publicity out of Cavanaugh’s death. And if that sounds a little ghoulish…well, it’s not out of keeping with the spirit of the picture as a whole.

After Stella came a conversation between ace historian/biographers Scott Eyman and Alan K. Rode. Scott was at the convention — well, he’s at Cinevent most years, but this year in particular he was there to promote (and sign copies of) his latest book, 20th Century Fox: Darryl F. Zanuck and the Creation of the Modern Film Studio, published under the aegis of Turner Classic Movies. There have been other histories of that studio (notably Michael Troyan’s Twentieth Century Fox: A Century of Entertainment), but Scott’s has a unique advantage — besides, that is, Scott’s trenchant historical analysis and eye for the telling detail. His is the first history of 20th Century Fox to encompass the moment when the studio ceased to exist — that is, its 2018 acquisition by the Disney Company, like a once-mighty Mesoamerican empire being absorbed and obliterated by the encroaching jungle. When Disney changed the name of its new subsidiary to Twentieth Century Pictures — ironically, returning to the name Darryl Zanuck and Joseph Schenck came up with 85 years earlier — for the first time in over a hundred years the name of William Fox was missing from the motion picture business (Fox himself was ousted in 1930). Scott’s book is both a chronicle and an elegy.

I mentioned back on Day 2 Alan K. Rode’s Michael Curtiz: A Life in Film, but another mention isn’t out of order. Back in the 1960s, when the Auteur Theory was reaching its maximum influence with people who indulged in such things, I remember a semi-serious joke that went around to the effect that Michael Curtiz was one director who “single-handedly disproves the Auteur Theory.” Well, to the contrary, Alan Rode’s biography makes a convincing case that Curtiz may have been more of an auteur than he usually gets credit for. In addition, Alan gives long-overdue credit to Curtiz’s wife, the writer Bess Meredyth, whose advice and script-doctoring efforts buttressed Curtiz’s career in much the same way Lady Alma Hitchcock did Sir Alfred’s. And if nothing else, we finish the book having been reminded how much Curtiz contributed to the Warner Bros. house style during the studio’s halcyon years — and continued to do so long after other creators of that style had decamped to greener pastures: Darryl Zanuck to create 20th Century Pictures and merge with Fox, Mervyn LeRoy to MGM, Hal Wallis to Paramount. If nothing else, Curtiz seems to have been able to work with Jack L. Warner longer than almost anyone.

After Scott and Alan’s colloquy (moderated by Caroline Breder-Watts) Alan introduced another Michael Curtiz Pre-Code, The Cabin in the Cotton (1932). Richard Barthelmess played the son of a family of sharecroppers who is hungry for education to better himself, but is forced back to grueling farm work when his father suddenly dies. When his planter-landlord’s daughter (Bette Davis) goes to bat for him, he’s allowed to complete his education and winds up graduating from the fields to the office of the plantation. There he is torn in his loyalties between the boss and his roots among the hardscrabble workers, just as he is between his new rich girlfriend and his lifelong sweetheart (Dorothy Jordan). It was the kind of role Barthelmess had been playing since the late 1910s for D.W. Griffith, and truth to tell by 1932 he was getting too old really to pull it off. But audiences then looked at him and saw the youthful lad they remembered from Way Down East and Tol’able David, while we today look and see a middle-aged actor trying to pass for nineteen. Fortunately for Barthelmess’s legacy, we also see the dogged, unshowy conviction that kept his career alive through the Pre-Code era. The Cabin in the Cotton also still plays — better than it did in 1932, if Michael Haynes’s citing of contemporary critics is any indication — thanks to Curtiz’s unpretentious direction, the irresistibly fetching Dorothy Jordan, and (last but not least) Bette Davis near the beginning of her career, coyly drawling the first of her signature lines: “Ah’d like t’kiss ya, but Ah jus’ washed my hair [‘hay-ah’].” Late in life, Bette was quoted as saying that was her all-time favorite line.

After Scott and Alan’s colloquy (moderated by Caroline Breder-Watts) Alan introduced another Michael Curtiz Pre-Code, The Cabin in the Cotton (1932). Richard Barthelmess played the son of a family of sharecroppers who is hungry for education to better himself, but is forced back to grueling farm work when his father suddenly dies. When his planter-landlord’s daughter (Bette Davis) goes to bat for him, he’s allowed to complete his education and winds up graduating from the fields to the office of the plantation. There he is torn in his loyalties between the boss and his roots among the hardscrabble workers, just as he is between his new rich girlfriend and his lifelong sweetheart (Dorothy Jordan). It was the kind of role Barthelmess had been playing since the late 1910s for D.W. Griffith, and truth to tell by 1932 he was getting too old really to pull it off. But audiences then looked at him and saw the youthful lad they remembered from Way Down East and Tol’able David, while we today look and see a middle-aged actor trying to pass for nineteen. Fortunately for Barthelmess’s legacy, we also see the dogged, unshowy conviction that kept his career alive through the Pre-Code era. The Cabin in the Cotton also still plays — better than it did in 1932, if Michael Haynes’s citing of contemporary critics is any indication — thanks to Curtiz’s unpretentious direction, the irresistibly fetching Dorothy Jordan, and (last but not least) Bette Davis near the beginning of her career, coyly drawling the first of her signature lines: “Ah’d like t’kiss ya, but Ah jus’ washed my hair [‘hay-ah’].” Late in life, Bette was quoted as saying that was her all-time favorite line.

After the dinner break, it was Laurel and Hardy time again, this time Their First Mistake (1932). Ollie, nagged by his wife (“the ever-popular Mae Busch”) for spending too much time with Stanley, gets the bright idea to adopt a baby to occupy the Missus while he gallivants with Stan. Coming home with the baby, he learns that his wife has left him, so The Boys must parent the child themselves. You can imagine how that works out; by the time the short has run its 20-minute course, it’s a toss-up as to which of the three is the most helpless infant.

Then came The Haunted Castle (1921), an early — and minor — F.W. Murnau, made before even his breakthrough with Nosferatu (1922). Any Murnau is worth seeing at least once — after all, he is one of the masters, he only directed 22 pictures, and seven of those are lost — but this one was frankly pretty tough sledding. (The English subtitles on the German intertitles didn’t help.) Despite the English title, there was nothing “haunted” about it; it wasn’t a ghost or horror story, but a straightforward (and pretty rudimentary) murder mystery. In fact, the original German title was Schloss Vogelöd (“Vogelöd Castle”), a simple identification of the setting. The scenario was adapted by Carl Mayer (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, The Last Laugh, Sunrise) from a novel by one Rudolf Stratz. Besides Murnau and Mayer, there are no names connected with The Haunted Castle worth mentioning. The cast was a gaggle of second-string actors whose names were unknown outside Germany then and are utterly forgotten today.

Then came The Haunted Castle (1921), an early — and minor — F.W. Murnau, made before even his breakthrough with Nosferatu (1922). Any Murnau is worth seeing at least once — after all, he is one of the masters, he only directed 22 pictures, and seven of those are lost — but this one was frankly pretty tough sledding. (The English subtitles on the German intertitles didn’t help.) Despite the English title, there was nothing “haunted” about it; it wasn’t a ghost or horror story, but a straightforward (and pretty rudimentary) murder mystery. In fact, the original German title was Schloss Vogelöd (“Vogelöd Castle”), a simple identification of the setting. The scenario was adapted by Carl Mayer (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, The Last Laugh, Sunrise) from a novel by one Rudolf Stratz. Besides Murnau and Mayer, there are no names connected with The Haunted Castle worth mentioning. The cast was a gaggle of second-string actors whose names were unknown outside Germany then and are utterly forgotten today.

Parole Fixer (1940) was a sprightly B-picture from Paramount about a conspiracy among gangsters and shyster lawyers to wangle undeserved paroles and fast-track criminals back to their nefarious ways. Supposedly based on J. Edgar Hoover’s book Persons in Hiding, the script was by the journeyman writer Horace McCoy (who did not live to see his 1935 novel They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? hailed as a 20th century classic), with crisp direction by Robert Florey. Top-billed William Henry, Virginia Dale, Robert Paige and Richard Denning were pretty lackluster, but the supporting cast included Lyle Talbot, Anthony Quinn, Marjory Gateson, Jack Carson and Louise Beavers.

The day finished up with…oh jeez, how shall I put this?…one of the most indelible screenings of the whole weekend. This was Sabaka (1954), a ghastly Technicolor train wreck that makes Plan 9 from Outer Space look like Close Encounters of the Third Kind. The plot concerned a young mahout (elephant wrangler) in India, Gunga Ram (Nino Marcel), seeking vengeance on the cult of Sabaka, the “fire goddess”, led by a charlatan priestess named Marku Ponjoy (prolific voice artist June Foray in a rare on-camera performance).

The day finished up with…oh jeez, how shall I put this?…one of the most indelible screenings of the whole weekend. This was Sabaka (1954), a ghastly Technicolor train wreck that makes Plan 9 from Outer Space look like Close Encounters of the Third Kind. The plot concerned a young mahout (elephant wrangler) in India, Gunga Ram (Nino Marcel), seeking vengeance on the cult of Sabaka, the “fire goddess”, led by a charlatan priestess named Marku Ponjoy (prolific voice artist June Foray in a rare on-camera performance).

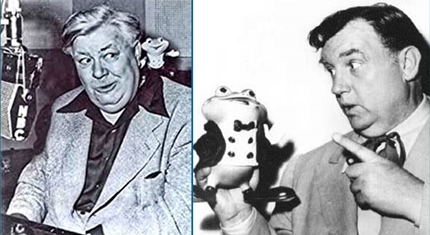

The provenance of Sabaka may not interest most readers, but it’s vastly more interesting than the movie itself, so here goes. The adventures of young Gunga Ram were a segment of a network-hopping kiddie show of early TV called Smilin’ Ed’s Gang, which Baby Boomers of a Certain Age may dimly remember. (Personally, I have no recollection of Gunga Ram, but I clearly remember the show, hosted by former kids’ radio personality Smilin’ Ed McConnell. I likewise remember his gang, including the puppets Midnight the Cat and Froggy the Gremlin, and his catchphrase “Plunk your magic twanger, Froggy!”) Series producer/director Frank Ferrin expanded one of these Gunga Ram segments into feature length, dispatched a second unit to India for local color, and shot the main body of the picture in and around Los Angeles, hiring a smattering of reputable actors (Boris Karloff, Reginald Denny, Victor Jory, Jay Novello, Vito Scotti) for fly-by cameos that could be filmed in a day or two and spliced in as needed. As for that location footage — you’d think a color picture shot in India would at least have pretty scenery, but no. The credited cinematographers were Jack McCoskey and Alan Stensvold, and whichever one Ferrin sent to India had trouble even focusing the camera (which must have had the Cinevent projectionists tearing their hair). Sabaka is available complete on YouTube if you’re curious. I’ll be interested to know how long you’re able to stick it out.

Just as Sabaka was going into release in 1954 — and in a possibly unrelated development — Smilin’ Ed McConnell dropped dead unexpectedly of a heart attack at 62. He was replaced by Andy Devine, and the show became Andy’s Gang until it finally ran its course at the end of 1960. Baby Boomers of a Slightly Younger Age may remember that incarnation of Froggy, Midnight, Gunga Ram and the rest of the gang.

Just as Sabaka was going into release in 1954 — and in a possibly unrelated development — Smilin’ Ed McConnell dropped dead unexpectedly of a heart attack at 62. He was replaced by Andy Devine, and the show became Andy’s Gang until it finally ran its course at the end of 1960. Baby Boomers of a Slightly Younger Age may remember that incarnation of Froggy, Midnight, Gunga Ram and the rest of the gang.

And so it was, at slightly before 1:00 a.m. Sunday morning, that those of us who stayed with Sabaka to the end repaired at last to our hotel rooms, secure in the knowledge that the final day of the final Cinevent would have nothing worse in store for us.