Picture Show 02 — Day 1

The serial for this year’s Columbus Moving Picture Show was The Purple Monster Strikes from 1945, one of the last 15-chapter productions that Republic Pictures mounted before rising costs and ebbing revenues forced the studio to downsize their serials to 12 installments. The first three chapters occupied the first hour of the first day, with four more coming on each of the succeeding days of the Picture Show.

The serial for this year’s Columbus Moving Picture Show was The Purple Monster Strikes from 1945, one of the last 15-chapter productions that Republic Pictures mounted before rising costs and ebbing revenues forced the studio to downsize their serials to 12 installments. The first three chapters occupied the first hour of the first day, with four more coming on each of the succeeding days of the Picture Show.

The premise of The Purple Monster Strikes is pretty much a howler. It seems the Emperor of Mars is planning to conquer the Earth and enslave all its inhabitants. But there’s a catch: The Martians have the technology to observe everything that goes on on Earth, and even to understand and speak all Earth languages (shades of the Babel fish from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy!), but they haven’t been able to develop a spacecraft capable of making the round trip from Mars to Earth and back. Fortunately for them, though, they’ve learned that Dr. Cyrus Layton (James Craven) is working on a “jet plane” that will be able to travel both ways (according to Bob Bloom’s program notes, Republic’s lawyers insisted on calling it a “jet plane” rather than a “rocket ship” for fear of legal action from Universal, whose Flash Gordon serials had rocket ships). So the Emperor sends a scout (Roy Barcroft as the Purple Monster — he actually introduces himself that way) on a one-way voyage to Earth with orders to steal Dr. Layton’s plans. The scout crash lands near Dr. Layton’s observatory, murders him with a capsule of Martian atmosphere (“carbo-oxide gas”) fatal to Earthlings, then commandeers his body, spending the rest of the serial going back and forth between Dr. Layton’s identity and his own, depending on his needs of the moment. While he’s at it, he enlists the aid of Garrett (Bud Geary), a local thug who’s been blackmailing the doctor.

Got all that? As interplanetary invasions go, this one is a pretty slapdash operation. Even so, all that stands between the Purple Monster and success is Dr. Layton’s niece Sheila (Linda Stirling, Republic’s reigning damsel in distress) and her boyfriend, two-fisted attorney Craig Foster (Dennis Moore). Preposterous as it all is, it makes a useful framework for the near-nonstop fisticuffs (I’d love to have had the breakaway furniture concession on the production), and the array of detailed miniatures (houses, trucks, cars, rockets, etc.) built by the resourceful Lydecker Brothers to crash, explode, burn, and go sailing off cliffs.

Chapter 1, “The Man in the Meteor”, has at least one memorable line, spoken by Craig Foster after the first of his many fistfights with the Purple Monster: “There was a man in here, a weird-looking person wearing tights and a helmet. He knocked me out and must have escaped across the terrace.” (Actually, he escaped into Dr. Layton, but Craig doesn’t know that, and won’t for several more chapters yet.)

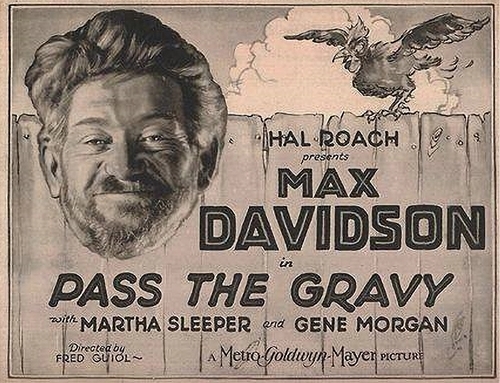

Next came a tribute to the forgotten Hal Roach comedy star Max Davidson (1875-1950). Or rather, “long-forgotten” I should say, because Davidson has been undergoing a bit of a rediscovery in recent years. Baby Boomers of a Certain Age will remember him from the Our Gang short Moan and Groan, Inc. (1929), in which the gang goes treasure-hunting in the basement of a supposedly haunted house. Max plays a homeless lunatic squatting in the derelict house; he’s harmless, but nevertheless pretty spooky, and he leads the gang and Edgar Kennedy the cop on a merry chase. I especially remember a delicious shiver as Max invites poor Farina to join him in an invisible Thanksgiving feast (“You…like…toikey?“). In fact, Max amassed quite a résumé by the time he retired in 1945; his IMDb filmography lists 200 titles, mostly uncredited bits between 1930 and 1945. But before that, in the mid-to-late 1920s, he was a popular star for Hal Roach — before his brand of “ethnic” (read “Jewish”) comedy went out of style as old-fashioned and in questionable taste. (Davidson didn’t live long enough to profit from the revival of ethnic comedy — Benny Rubin, Myron Cohen, Jack Carter, Alan King, Shelley Berman et al. — in the 1950s and ’60s.)

Next came a tribute to the forgotten Hal Roach comedy star Max Davidson (1875-1950). Or rather, “long-forgotten” I should say, because Davidson has been undergoing a bit of a rediscovery in recent years. Baby Boomers of a Certain Age will remember him from the Our Gang short Moan and Groan, Inc. (1929), in which the gang goes treasure-hunting in the basement of a supposedly haunted house. Max plays a homeless lunatic squatting in the derelict house; he’s harmless, but nevertheless pretty spooky, and he leads the gang and Edgar Kennedy the cop on a merry chase. I especially remember a delicious shiver as Max invites poor Farina to join him in an invisible Thanksgiving feast (“You…like…toikey?“). In fact, Max amassed quite a résumé by the time he retired in 1945; his IMDb filmography lists 200 titles, mostly uncredited bits between 1930 and 1945. But before that, in the mid-to-late 1920s, he was a popular star for Hal Roach — before his brand of “ethnic” (read “Jewish”) comedy went out of style as old-fashioned and in questionable taste. (Davidson didn’t live long enough to profit from the revival of ethnic comedy — Benny Rubin, Myron Cohen, Jack Carter, Alan King, Shelley Berman et al. — in the 1950s and ’60s.)

Three of the four shorts in the Picture Show’s tribute were from this period (the fourth, 1914’s Bill Joins the W.W.W.’s, featured Max in support of stars Tammany Young and Fay Tincher at Universal). Two of the Hal Roach three, Don’t Tell Everything and Should Second Husbands Come First? (both 1927) were directed by future Oscar winner Leo McCarey. The best of the lot was Pass the Gravy (’28), in which Max’s dimwitted son (mega-freckle-faced Spec O’Donnell) accidentally kills the neighbor’s prize-winning rooster, and the family compounds the offense by unwittingly roasting the deceased bird and serving it to the neighbor for dinner — with its “First Prize” ribbon still attached to its drumstick. Eric Grayson’s program notes call Pass the Gravy Max’s masterpiece, and I believe it; it’s a riot, and the Library of Congress evidently agrees — it was added to their National Film Registry in 1998. Alas, most of Max Davidson’s silent output is lost now, but enough has survived that the Picture Show promises more such tributes in years to come.

The first feature of the day was The Blue Veil (1951), a real two-hanky weeper. Jane Wyman stars as a young wife and mother whose husband has died in World War I and whose baby lives only a day or two. At loose ends and grieving, she takes a job as nursemaid to an infant whose mother died in childbirth. What begins as just a temporary situation to help ease her bereavement turns into a lifelong calling, and the movie becomes an episodic drama, almost an anthology film, as she moves from family to family for over thirty years, often working for parents who are, shall we say, less than wholly involved in their children’s lives.

The first feature of the day was The Blue Veil (1951), a real two-hanky weeper. Jane Wyman stars as a young wife and mother whose husband has died in World War I and whose baby lives only a day or two. At loose ends and grieving, she takes a job as nursemaid to an infant whose mother died in childbirth. What begins as just a temporary situation to help ease her bereavement turns into a lifelong calling, and the movie becomes an episodic drama, almost an anthology film, as she moves from family to family for over thirty years, often working for parents who are, shall we say, less than wholly involved in their children’s lives.

The Blue Veil was actually a remake of a French film of the same title (Le Voile Bleu in French), produced in 1942 under the German occupation, and hence not seen in the U.S. until 1947. It got only a spotty distribution then, but it caught the eye of producer Jerry Wald, who nailed down the remake rights. Wald’s first idea was to cast Bette Davis as the heroine, or even to coax Greta Garbo out of retirement, but his cooler head prevailed and he settled on Jane Wyman, whom he had ushered to an Oscar in 1948’s Johnny Belinda. And I say “settled on“, not “settled for“, because it was an inspired choice. This came right smack in the middle of Wyman’s apotheosis years, which spanned from The Yearling in 1946 to 1954, when she made All That Heaven Allows and got her fourth and final Oscar nomination for Magnificent Obsession. She was nominated for The Blue Veil too, and might well have won had she not been up against Vivien Leigh in A Streetcar Named Desire.

Also nominated for The Blue Veil was Joan Blondell as a fading Broadway musical star whose laser focus on reviving her career threatens to forfeit the affections of daughter Natalie Wood. Joan was as good as ever, of course, but why she landed her only nomination for this over any number of her other performances — A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (’45), Nightmare Alley (’47), The Cincinnati Kid (’65) — is a bit of a mystery. Ah well, let’s not quibble, she was overdue. Anyhow, she and Wyman were just first and second among equals in the closest thing to an all-star cast that RKO Radio could field at that stage of its decline-and-fall. Just look at the thumbnail portraits on this poster surrounding Jane Wyman like a rectangular halo (from bottom left): Richard Carlson, Joan, Charles Laughton, Agnes Moorehead, Don Taylor, Audrey Totter, Cyril Cusack, Natalie, Everett Sloane. Add to them Vivian Vance, Alan Napier, Warner Anderson, Les Tremayne, Dan O’Herlihy, Harry Morgan and others, and you’ve got quite an ensemble. Led by Wyman’s resolutely unsentimental performance, The Blue Veil earns its tears honestly.

Then came Come Next Spring (1956), a rural domestic drama from the waning years of Republic Pictures (just as The Blue Veil had been from the waning years of RKO Radio). The screening was introduced by Steven C. Smith, author of Music by Max Steiner: The Epic Life of Hollywood’s Most Influential Composer. Mr. Smith had expressed an interest in making the introduction because he regards Come Next Spring as one of Steiner’s best pictures of the 1950s, and the setting for one of his best scores. Come Next Spring is a particular favorite of mine too, so I was most interested in hearing Mr. Smith’s intro (having been highly gratified by what he wrote about it in his biography of the composer). Unfortunately, I dawdled a bit too long in the dealers’ room, so I missed the first minute or two of his remarks. Consequently, I was pleasantly surprised when I heard him mention my name: “For more information, I refer you to Jim Lane…” I thought he was referring to the notes I wrote for the Picture Show program book, but actually (I learned when I met him later) he was talking about my Cinedrome post from 2014, which he discovered while researching his book on Steiner. Since he was kind enough to plug my post, I’m happy to return the compliment. Click the link above and hop on over to Amazon for your own copy of Music by Max Steiner. Steiner may not be the greatest of all film composers (though I believe he is), but without him Bernard Herrmann, Henry Mancini, Elmer Bernstein, John Williams, Dimitri Tiomkin, Jerry Goldsmith, David Raksin, Alfred or Randy Newman, you name ’em — none of them would have had the careers they did. And besides, the book is a marvelous read.

Then came Come Next Spring (1956), a rural domestic drama from the waning years of Republic Pictures (just as The Blue Veil had been from the waning years of RKO Radio). The screening was introduced by Steven C. Smith, author of Music by Max Steiner: The Epic Life of Hollywood’s Most Influential Composer. Mr. Smith had expressed an interest in making the introduction because he regards Come Next Spring as one of Steiner’s best pictures of the 1950s, and the setting for one of his best scores. Come Next Spring is a particular favorite of mine too, so I was most interested in hearing Mr. Smith’s intro (having been highly gratified by what he wrote about it in his biography of the composer). Unfortunately, I dawdled a bit too long in the dealers’ room, so I missed the first minute or two of his remarks. Consequently, I was pleasantly surprised when I heard him mention my name: “For more information, I refer you to Jim Lane…” I thought he was referring to the notes I wrote for the Picture Show program book, but actually (I learned when I met him later) he was talking about my Cinedrome post from 2014, which he discovered while researching his book on Steiner. Since he was kind enough to plug my post, I’m happy to return the compliment. Click the link above and hop on over to Amazon for your own copy of Music by Max Steiner. Steiner may not be the greatest of all film composers (though I believe he is), but without him Bernard Herrmann, Henry Mancini, Elmer Bernstein, John Williams, Dimitri Tiomkin, Jerry Goldsmith, David Raksin, Alfred or Randy Newman, you name ’em — none of them would have had the careers they did. And besides, the book is a marvelous read.

Now here I insert my program notes for Come Next Spring. However, those notes are adapted from my 2014 post, which you can read here. I go into a good deal more detail, plus the picture was filmed in a small California town about 35 miles from my front door, so I include a number of then-and-now photographs of the picture’s locations. So if you like, you can click over to my 2014 post and skip the next 13 paragraphs.

By the the summer of 1955, Republic Pictures was on its last legs as a movie-producing entity. It had once been prolific, cranking out horse operas, serials and hillbilly comedies for small towns, with occasional “prestige” pictures like Sands of Iwo Jima (1949) and John Ford’s The Quiet Man (1952). Now, taking one last shot at prestige, studio boss Herbert J. Yates dispatched a unit up north to the California Gold Country town of Ione (pronounced “eye-own”). There they made Come Next Spring, arguably — with the possible exception of Orson Welles’s 1948 Macbeth — the best movie ever to come out of Republic Pictures that didn’t involve John Ford or John Wayne. (And no, I’m not forgetting Nicholas Ray’s Johnny Guitar.)

Come Next Spring was directed by R.G. (“Bud”) Springsteen, the epitome of the reliable but unexceptional studio workhorse. Actually, “plowhorse” would be more like it; by the time of Come Next Spring he had already directed over 50 features in ten years — mostly Republic programmers running about an hour. He never wasted film, time or money — a triple virtue guaranteed to please the penny-pinching Yates. It would also earn Springsteen a secure niche in television until he retired in 1970.

The secret ingredient of Come Next Spring was its writer, Montgomery Pittman. Pittman might be described as “unjustly forgotten today” — except that the sorry truth is he died before even being noticed, succumbing to throat cancer at 42 in 1962. But in his brief 11-year career he was prolific, resourceful and original, leaving a varied body of movie and TV work — and a frustrating hint of what might have been if even another ten or 15 years had been granted to him.

Born in Oklahoma in 1920, Pittman, by his own colorful account, left home while still a teenager, working with a traveling carnival as (no joke!) a snake-oil salesman. After service in World War II he landed first in New York, then Los Angeles, hoping to become an actor. But he found more work and better money writing for TV, eventually moving into directing as well. Along the way, in 1952, he married Maurita Gilbert Jackson, a widow whose ten-year-old daughter Sherry was already working as a child actress. Pittman’s relationship with his new stepdaughter would bear fruit in Come Next Spring.

In the mid-’50s Pittman was a contract writer for Warner Bros. Television on the studio’s westerns Cheyenne, Sugarfoot and Maverick, and the private-eye series 77 Sunset Strip, Surfside 6 and Hawaiian Eye, often directing his own scripts. In the early ’60s, just as his time on Earth was running out, Pittman wrote and directed three episodes of Rod Serling’s original The Twilight Zone on CBS, making him the only person during the show’s entire run who both wrote and directed an episode — and he did it three times. Those three are among the very best episodes that weren’t written by The Twilight Zone’s “Big Three” (Serling, Charles Beaumont and Richard Matheson). The titles are worth mentioning: “Two”, a post-apocalyptic drama starring Charles Bronson and Elizabeth Montgomery; “The Last Rites of Jeff Myrtlebank”, featuring James Best, Edgar Buchanan and Sherry Jackson from Come Next Spring; and “The Grave” with Lee Marvin as an Old West bounty hunter, plus Elen Willard as a female character named Ione — an unmistakable hat-tip to the town where Come Next Spring was filmed.

Monty Pittman’s pitch-perfect script tells an unusual yet straightforward story: Matt Ballot, a reformed alcoholic (Steve Cochran), returns to his home in 1920s Arkansas hoping to make amends to his wife Bess (Ann Sheridan), his children (Sherry Jackson, Richard Eyer), and his rural community, all of whom he abandoned in a drunken haze years before. There are strong performances all around, underscored by the great Max Steiner (including a title song written with Lenny Adelson that was a popular hit for Tony Bennett, who sings it under the credits).

When she made Come Next Spring, Ann Sheridan was several years past her glamour days as Warner Bros.’ “Oomph Girl” (a nickname she detested). Even at the height of her career, her talent never got the respect it deserved — not surprising for a studio dominated by male stars that already had Bette Davis and Olivia de Havilland — but she had remarkable depth and range. All through World War II she was well-liked by co-workers, popular with audiences, and underrated by critics. That combination held right up to her untimely death at 51 in 1967 (and the “underrated” part has stayed with her ever since).

Steve Cochran, unlike Sheridan, was never underrated…exactly. But ever since his sudden death from a lung infection at 48 in 1965, the question has haunted movie buffs: Why didn’t this guy ever become a bigger star? Partly, it may have been his tabloid lifestyle of womanizing, carousing and boozing, flouting his fragile health (a heart murmur kept him out of World War II). Anyhow, he never managed to break the mold of thugs and unsavories into which he had been cast, certainly not the way actors like Robert Mitchum, Richard Widmark and Dana Andrews had been able to do. Still, he never gave a bad performance even in the weakest of his 39 pictures. Matt Ballot was the role of Cochran’s life, and he knew it. When his friend Pittman brought him the script, Cochran bought it for his own company, Robert Alexander Productions (named for his real first and middle names), then sold it to Republic on the condition that he and Sherry Jackson play the parts Pittman had written for them. If Cochran had given this performance for any studio but Republic it might have made all the difference in his career. But probably no other studio would have cast him as anything but a ne’er-do-well or a hoodlum. It may even be that no other studio would have touched Come Next Spring at all. That, sad to say, was just Steve Cochran’s luck.

Sonny Tufts played Leroy Hightower, an admirer of Bess Ballot’s who resents Matt’s sudden return. Bowen Charles Tufts III is one of Hollywood’s sad cases. He was not without talent, but not talented enough to overcome some poor life and career choices. Scion of a prominent Boston family (his great-uncle founded Tufts University), he shunned the family banking business to study opera at Yale. Classified 4-F during World War II due to a college football injury, he found stardom in Hollywood when handsome leading men were scarce. Alcohol was his undoing, and his off-screen behavior became notorious. He gave probably his best performance in Come Next Spring, and a few years later he reportedly sobered up in hopes of playing Jim Bowie in John Wayne’s The Alamo. True or not, by then his name was a Hollywood punchline, and the idea was probably a non-starter. He died of pneumonia in 1970, age 58.

As if Ann Sheridan, Steve Cochran, Sonny Tufts and a first-rate supporting cast were not enough, there’s another reason to see Come Next Spring, one that all by itself would more than suffice: the extraordinary performance of 13-year-old Sherry Jackson as Annie, Bess and Matt’s mute daughter. Already a veteran (coming off her second season as Danny Thomas’s oldest daughter on Make Room for Daddy), she, like Cochran, gave the performance of her life in Come Next Spring. With her enormous, expressive eyes and every tiny movement of the corners of her mouth, she makes Annie’s thoughts as plain as if she spoke them out loud — and all without uttering a sound. It is, without question, one of the greatest child performances ever put on film.

As if Ann Sheridan, Steve Cochran, Sonny Tufts and a first-rate supporting cast were not enough, there’s another reason to see Come Next Spring, one that all by itself would more than suffice: the extraordinary performance of 13-year-old Sherry Jackson as Annie, Bess and Matt’s mute daughter. Already a veteran (coming off her second season as Danny Thomas’s oldest daughter on Make Room for Daddy), she, like Cochran, gave the performance of her life in Come Next Spring. With her enormous, expressive eyes and every tiny movement of the corners of her mouth, she makes Annie’s thoughts as plain as if she spoke them out loud — and all without uttering a sound. It is, without question, one of the greatest child performances ever put on film.

Ann Sheridan, Steve Cochran, Sonny Tufts, Sherry Jackson: All of them were never better than in Come Next Spring, maybe even never as good. Hmmm. Maybe this Bud Springsteen was a better director than he ever got credit for.

And one final thing. This is a promise: The very last shot of the picture, just before it fades to “The End”, is something you’ll remember as long as you live. Mark my words.

Before we move on, here’s a funny little factoid I stumbled across while looking for images of Come Next Spring. I found the Belgian poster for the picture, which gave the title twice, once in French (Celui Qu’on N’attendait Plus) and once in Dutch (De Man die Men Niet Meer Verwachtte). Both versions translate to roughly the same thing: The Man They No Longer Expected. Well, that fits well enough, if “come next spring” is too much a regional Americanism to translate, but I wonder why they didn’t use “next spring” (Le Printemps Prochain / Volgende Lente) or “when spring comes” (Quand Vient le Printemps / Als de Lente Komt). After all, the phrase “come next spring” pops up several times in the dialogue and they must have translated that somehow. Just one of those unimportant little questions we can never know the answer to.

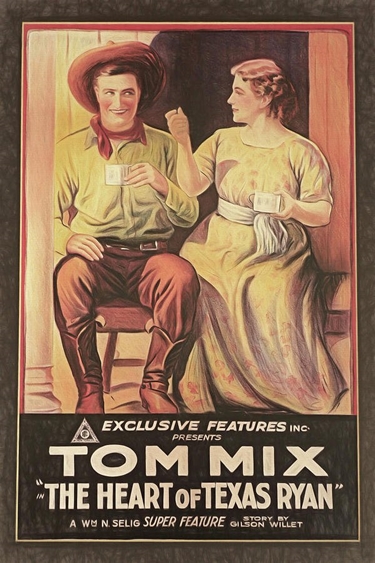

The first silent feature of the weekend was The Heart of Texas Ryan (1917) an early Tom Mix picture. “Early” in this case must be qualified. By this time Mix had been in movies for eight years and had 170 titles on his filmography — mostly one- and two-reel shorts. But he hadn’t become “Tom Mix” yet, the straight-arrow hero in the white ten-gallon hat. His superstardom was just around the corner, though, probably as a result of his leaving Selig Polyscope to sign with Fox Film Corp., which happened after ten more pictures, in late 1917 (his first release of 1918, Cupid’s Roundup, was for Fox). In Texas Ryan, contrary to what you might expect, he doesn’t play the title role (and Variety’s review of 2/23/17 doesn’t even mention his name). So this poster, with his name above and larger than the title, is a bit misleading. It’s not from the picture’s original release, in February ’17 from K-E-S-E (Kleine-Edison-Selig-Essanay). The poster is from a 1923 reissue (by which time Mix was the one of the biggest stars in the world) from Exclusive Features Inc., whoever they were.

The first silent feature of the weekend was The Heart of Texas Ryan (1917) an early Tom Mix picture. “Early” in this case must be qualified. By this time Mix had been in movies for eight years and had 170 titles on his filmography — mostly one- and two-reel shorts. But he hadn’t become “Tom Mix” yet, the straight-arrow hero in the white ten-gallon hat. His superstardom was just around the corner, though, probably as a result of his leaving Selig Polyscope to sign with Fox Film Corp., which happened after ten more pictures, in late 1917 (his first release of 1918, Cupid’s Roundup, was for Fox). In Texas Ryan, contrary to what you might expect, he doesn’t play the title role (and Variety’s review of 2/23/17 doesn’t even mention his name). So this poster, with his name above and larger than the title, is a bit misleading. It’s not from the picture’s original release, in February ’17 from K-E-S-E (Kleine-Edison-Selig-Essanay). The poster is from a 1923 reissue (by which time Mix was the one of the biggest stars in the world) from Exclusive Features Inc., whoever they were.

Texas Ryan (played by Bessie Eyton) is actually the daughter of the rancher (George Fawcett) for whom Tom works as a cowpuncher. His character is Jack “Single-Shot” Parker (“Single-Shot” Parker was the title of another of the picture’s reissues); Parker is a rootin’-tootin’ hell-raising troublemaker who spends his weekends brawling and shooting up the nearby town of Cactus Bend. Single-Shot gets on the bad side of the local marshal “Dice” McAllister (Frank Campeau), mainly by beating the snot out of him with McAllister’s own boot. Worse, the marshal is a “dirty cop”, working in cahoots with the bandit Jose Mandero (William Ryno).

As the movie opens, Texas Ryan is returning to the wide-open spaces after two years at an eastern college. Single-Shot and Mandero both catch sight of her and are smitten. Single-Shot resolves to mend his lawless ways and be worthy of the lady’s love; Mandero resolves to abduct the lady, for purposes that (this being 1917) are left discreetly unspecified. First Single-Shot rescues Texas, then later, when Mandero kidnaps Single-Shot for revenge and plans to kill him, Texas rescues him by paying a hefty ransom. Happy ending, iris-out.

The Heart of Texas Ryan is a fast-paced, appealing actioner, its excitement undimmed after 106 years. It is enlivened, like nearly all of Tom Mix’s surviving pictures, by his already-evident penchant for perilous, positively insane stunts. (He scorned to use a double and was frequently injured, which must have had the Fox front office tearing their hair.) At one point in Texas Ryan, as Mandero’s gang leads him on horseback with his hands tied behind his back, he escapes by leaping from the saddle and tumbling ass-over-teakettle, hands still tied, down a hill so steep it’s practically a cliff. His horse here is almost as game as he is, a dark-maned gray willing to carry him anywhere. (It would be several years before Mix teamed up with “Tony the Wonder Horse”, an intelligent Tennessee Pacer that became almost as big a star as he was.)

We returned from the dinner break for Laurel and Hardy in Come Clean (1931). The Hardys are enjoying an evening at home when an unwelcome visit from the Laurels turns things upside down. Stan wants ice cream, so he and Oliver venture out to get some, leading to a frustrating episode with an ice cream sales clerk (Charlie Hall). On the way home, they rescue a woman (Mae Busch) who has jumped into the river to kill herself. Ungrateful at being rescued, the harridan demands that they now must take care of her, presumably forever. The rest of the short details The Boys’ efforts to keep Busch hidden from their suspicious wives (Gertrude Astor, Linda Loredo) until the ironic dénouement.

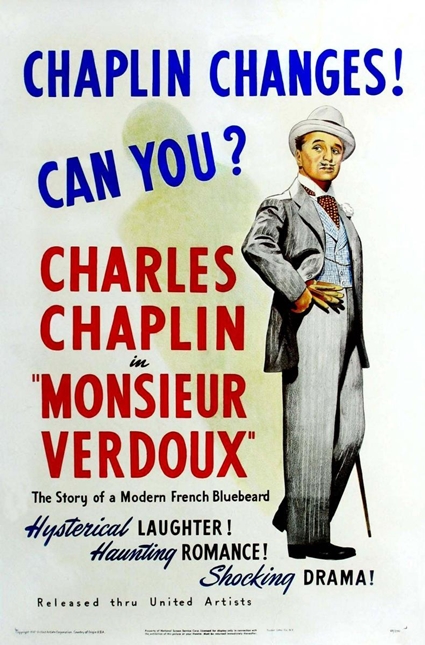

Then it was Monsieur Verdoux (1947), Charles Chaplin’s black-comedy fantasia on the career of serial killer Henri Landru, who murdered somewhere between seven and 83 people between 1915 and 1919, then went to the guillotine for 11 of them in 1922. Chaplin claimed that the premise for Verdoux arose out of a negotiation with Orson Welles (who got a story credit in the finished film), but the Picture Show program notes by Chaplin and Max Linder biographer Lisa Stein Haven say Chaplin had been percolating the idea since 1921. In any event, the picture was an echoing flop in 1947 (though the French liked it) but has grown in stature over the years since Chaplin allowed it back in circulation in the 1960s, to the point where it was one of the clear headliners at this year’s Picture Show.

But not every work by a master is a masterwork, and I’ve never much cared for Monsieur Verdoux (though I like it better than the absurdly overrated The Great Dictator). I find Verdoux‘s comedy flatfooted, forced and unfunny (except for Martha Raye, hilarious as the one intended victim whom Chaplin’s Verdoux, try as he might, just can’t manage to kill). And when Chaplin shifts gears into moralizing about individual murders vs. the organized mass killing of war, his channeling of George Bernard Shaw strikes me as glib, smug and condescending. The day may well come when I revisit Monsieur Verdoux, slap my forehead and cry, “What a fool I’ve been!” But that day is not yet here. I elected to spend the two hours browsing the dealers’ room, postponing my eating crow about Chaplin’s picture to some other time.

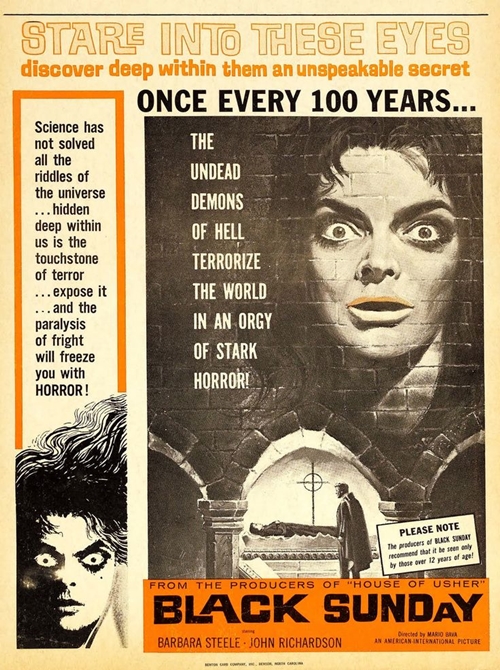

When I was a pre- and early-teen adolescent in the late 1950s and early ’60s, my friends and I were amateur connoisseurs of the horror movies of the day — The Tingler and House on Haunted Hill (1959); 13 Ghosts and The Horror Chamber of Dr. Faustus (’60); The Mask, The Pit and the Pendulum and The Curse of the Werewolf (’61), and many more. In the spring of 1961, there was one that — at least in my neck of the woods — was the movie to see; it seemed that all the guys were talking about it, but for some reason I never got around to seeing it. Not then, and not as its reputation grew over the ensuing decades; not until the end of the first day of this year’s Columbus Moving Picture Show. This was Black Sunday (1960), the Italian import from first-time director and future horror master Mario Bava.

When I was a pre- and early-teen adolescent in the late 1950s and early ’60s, my friends and I were amateur connoisseurs of the horror movies of the day — The Tingler and House on Haunted Hill (1959); 13 Ghosts and The Horror Chamber of Dr. Faustus (’60); The Mask, The Pit and the Pendulum and The Curse of the Werewolf (’61), and many more. In the spring of 1961, there was one that — at least in my neck of the woods — was the movie to see; it seemed that all the guys were talking about it, but for some reason I never got around to seeing it. Not then, and not as its reputation grew over the ensuing decades; not until the end of the first day of this year’s Columbus Moving Picture Show. This was Black Sunday (1960), the Italian import from first-time director and future horror master Mario Bava.

Originally titled La Maschera del Demonio (The Mask of the Demon), the picture underwent a major makeover when American International Pictures (AIP) acquired the U.S. distribution rights. Some violent and erotic footage was scaled back or eliminated, dialogue was re-dubbed, and the picture’s musical score by Roberto Nicolosi was replaced by one from the American Les Baxter. All in all, AIP could claim some justification for the tagline, “From the producers of House of Usher“, because more than simply distributing the movie, they had actually produced a picture that differed perceptibly from the one that had only a middling success in Italy.

In the version that cleaned up at the American box office for AIP, British actress Barbara Steele plays Asa (“Ah-zah”) Vajda, a vampire in 17th century Moldavia who, along with her vampire lover Javutich, is condemned to death for witchcraft by her brother Griabi. As she sees the bronze-spiked mask that is to be hammered onto her face, Asa howls a curse on Griabi and his descendants — and then she appears to summon a sudden storm that prevents the villagers from burning her body at the stake.

Two hundred years later, a physician and his assistant are traveling through the country on their way to a medical conference when their carriage loses a wheel. Exploring a nearby crypt while their coachman makes repairs, they unwittingly revive Asa and Javutich’s corpses, and the two vampires begin wreaking their vengeance, especially on Griabi’s multi-great-granddaughter Katia (Barbara Steele again), whom Asa believes is the reincarnation of her own wicked soul.

My friends back in 1961 were right; Black Sunday absolutely lives up to its reputation. After sixty-plus years, even in heavy-shadowed black and white with little actual blood but an atmosphere of erotic dread, the picture packs a mighty punch. I can only (and barely) imagine the impact it had in 1961. No wonder all the guys were talking about it. Frankly, I’m just as glad I had to wait; I’m not sure I could have handled it back then. Director Bava weaves his Gothic tapestry with an undercurrent of breathless sex and violence that a 13-year-old male in 1961 would have felt but scarcely understood.

And with that we called it a day.