Shirley Temple Revisited, Part 14

And so we come to the endgame of the Shirley Temple Phenomenon. It’s the summer of 1939; Shirley is 11 years old — though she and the rest of the world still think she’s only ten — and she’s bumping up against a principle that won’t even be articulated until 1997: what critic Louis Menand called “The Iron Law of Stardom”. In a New Yorker article by that title published in March ’97, Menand posited his “Iron Law” as one of the immutable laws of the universe, like gravity or the speed of light. Put simply, the Iron Law is this: stardom never lasts more than three years. Menand was careful, however, to distinguish between “stardom” and “being a star”. Once a star, always a star, he said, but actual stardom is something else — “the period of inevitability, the time when everything works in a way that makes you think it will work that way forever…the intersection of personality with history, a perfect congruence of the way the world happens to be and the way the star is.” Thus, Menand explained, Elizabeth Taylor remained a star all her life by virtue of being the person who was Elizabeth Taylor from 1963 (Cleopatra) to 1966 (Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?), and Al Pacino remains a star as the person who was Al Pacino from 1972 (The Godfather) to 1975 (Dog Day Afternoon).

And so we come to the endgame of the Shirley Temple Phenomenon. It’s the summer of 1939; Shirley is 11 years old — though she and the rest of the world still think she’s only ten — and she’s bumping up against a principle that won’t even be articulated until 1997: what critic Louis Menand called “The Iron Law of Stardom”. In a New Yorker article by that title published in March ’97, Menand posited his “Iron Law” as one of the immutable laws of the universe, like gravity or the speed of light. Put simply, the Iron Law is this: stardom never lasts more than three years. Menand was careful, however, to distinguish between “stardom” and “being a star”. Once a star, always a star, he said, but actual stardom is something else — “the period of inevitability, the time when everything works in a way that makes you think it will work that way forever…the intersection of personality with history, a perfect congruence of the way the world happens to be and the way the star is.” Thus, Menand explained, Elizabeth Taylor remained a star all her life by virtue of being the person who was Elizabeth Taylor from 1963 (Cleopatra) to 1966 (Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?), and Al Pacino remains a star as the person who was Al Pacino from 1972 (The Godfather) to 1975 (Dog Day Afternoon).By this reasoning, and with hindsight, we can see that Shirley in 1939 fits the pattern. She remains a star, but it’s by virtue of being the person who was Shirley Temple from 1934 (Little Miss Marker and Bright Eyes) to 1937 (Wee Willie Winkie and Heidi). Nineteen-forty will round out not only the decade, but her reign atop the box office and her career at 20th Century Fox as well.

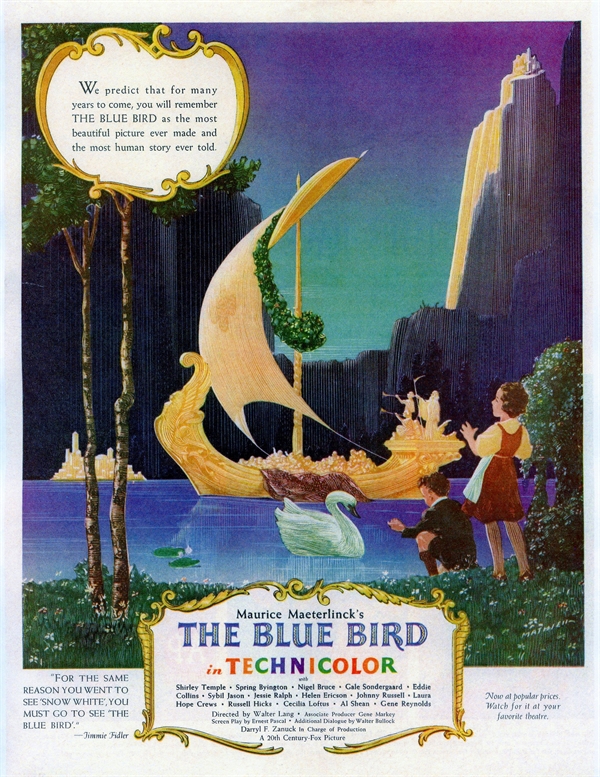

The Blue Bird

(released January 19, 1940)

The Blue Bird was Shirley’s second brush with a Nobel Prize winner, after Rudyard Kipling and Wee Willie Winkie. Belgian poet, essayist and playwright Maurice Maeterlinck (1862-1949) was a leading proponent of the Symbolist movement in European art and literature of the late 19th century. His most influential and commercially successful play was probably Pelleas and Melisande (1893), a doomed-lovers tragedy that inspired numerous operas, all of which are performed these days far more often than the original play.

The Blue Bird was Shirley’s second brush with a Nobel Prize winner, after Rudyard Kipling and Wee Willie Winkie. Belgian poet, essayist and playwright Maurice Maeterlinck (1862-1949) was a leading proponent of the Symbolist movement in European art and literature of the late 19th century. His most influential and commercially successful play was probably Pelleas and Melisande (1893), a doomed-lovers tragedy that inspired numerous operas, all of which are performed these days far more often than the original play.

A close second to that, however, would have to be The Blue Bird, which was an immediate hit when it premiered at Konstantin Stanislavski’s Moscow Art Theatre in 1908. When Maeterlinck won the Nobel Prize in 1911 “in appreciation of his many-sided literary activities, and especially of his dramatic works,” the citation explicitly mentioned “a poetic fancy, which reveals, sometimes in the guise of a fairy tale, a deep inspiration”. This could only have been a reference to The Blue Bird, which was then sweeping the world and would have been prominent in the minds of the Swedish Academy (in those days, commercial success was not considered a disadvantage when Nobel Prize time rolled around).

The Blue Bird recounts the many adventures of the boy Tyltyl (“til-til”) and his little sister Mytyl (“mee-til”), the children of a poor woodcutter somewhere in Central Europe. One night the children are roused from sleep by a bent and withered old woman who, changing shape, is revealed as a beautiful fairy named Berylune. The fairy dispatches the two on a quest to find the Blue Bird of Happiness, in which they are to be accompanied by their dog and cat, both of whom are magically given human shape for the occasion. Also accompanying them, and also in human form, are the spirits of Bread, Water, Milk, Fire and Light. The children’s search takes them to many fanciful places — the palace of Berylune, which once belonged to the infamous Bluebeard; the Palace of Night, deep underground; the Graveyard of the Happy Dead, where they are briefly reunited with their late grandparents and seven brothers and sisters who all died in childhood; the Palace of Happiness, where luxuries and joys abound; and the Kingdom of the Future, where they meet children waiting to be born, all of whom have a knowledge of their destiny that they will lose once they begin their earthly lives (Tyltyl and Mytyl even meet their own future little brother, who already knows that he too will die in infancy). In the final scene Tyltyl and Mytyl awaken back in their own beds; their parents think they have only slept through the night, but the children know better — how could both have had the same dream? Whether dream or magic, their quest has failed, they never did find the elusive bird they sought. Then, to their surprise, they see that the Blue Bird is right there in their own house, and was there all along. At the very end the bird flies away, and Tyltyl turns to the audience and says, “If any of you should find him, would you be so very kind as to give him back to us?…We need him for our happiness, later on….”

My memory of Maeterlinck’s play is unfortunately sketchy; it’s been more than 40 years since I read it, and I wouldn’t read it again if you held a gun to my brother’s head. I found it to be long, turgid and utterly pointless, and it calls for spectacular effects that might have been wonderful to look at but make awfully dry reading (given the state of stagecraft in 1908, Stanislavski’s set designers, carpenters and stage managers must have been tearing their hair as opening night drew near). The play was a great success in the first and second decades of the last century, no doubt because the fantastic effects it calls for made for quite a wondrous spectacle to behold. But after that first flush of success and the afterglow of the Nobel Prize, its charm quickly evaporated.

The reason isn’t hard to figure out. Despite its elaborate settings and special effects, and characters symbolic of everything under the sun, The Blue Bird simply has no story. Why do Tyltyl and Mytyl undertake this convoluted journey? Why don’t they just tell the old hag to get lost, then roll over and go back to sleep? The kids have nothing at stake in this quest; they’re just gallivanting around in Maeterlinck’s head. In The Wizard of Oz — to cite an example that will come up more than once in the course of this post — what Dorothy and her companions are after is crystal-clear, and there’s never any doubt what’s at stake. That’s why The Blue Bird hasn’t been staged in 90 years, and is never even read except under duress by hapless students in university drama classes — while L. Frank Baum’s tale still sells thousands of copies every year.

With all that said, 20th Century Fox’s 1940 version of The Blue Bird has been given a bum rap over the years. The main thrust of the rap is that The Blue Bird was Fox’s attempt to duplicate the success of MGM’s The Wizard of Oz (this has also fed the myth that Shirley “lost” the role of Dorothy). It would be closer to the truth to say that both pictures were attempts to duplicate the success of Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. (In which, by the way, both failed. The Blue Bird, in Time Magazine’s inevitable snark line, “laid an egg”, but Oz didn’t do much better, either with the critics or at the box office; it was voted “Most Colossal Flop” of 1939 by the Harvard Lampoon, and it took 16 years and two reissues for the picture to turn a profit.)

Now let’s stipulate right up front that The Blue Bird is nowhere near the same league as The Wizard of Oz — but what movie is? Of all the many differences between them, the most basic one, and the one that most redounds to the advantage of The Wizard of Oz, is that MGM was adapting L. Frank Baum while 20th Century Fox was adapting Maurice Maeterlinck.

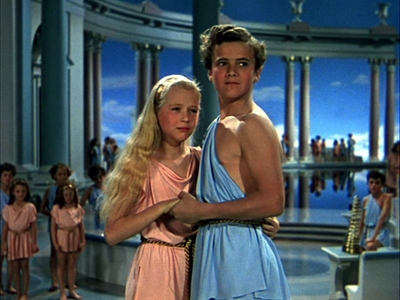

Or trying to. The Blue Bird‘s greatest faults are inherent in Maeterlinck’s play; this was one case where Fox might have been justified in jettisoning everything but the title. Instead, Ernest Pascal’s script made an honest effort (with moderate success) to streamline, simplify and motivate the wild excesses of Maeterlinck’s fantasy. First, merely as a practical matter, the birth order of the lead siblings was reversed, making Mytyl (Shirley) the older and Tyltyl (Johnny Russell) the younger. The size of their expedition was streamlined, with their only companions being the cat Tylette (Gale Sondergaard, right) and dog Tylo (Eddie Collins, next to her). Of Maeterlinck’s five spirits, only Light remained (played by Helen Ericson), and she served, logically enough, as the children’s guide on their quest. (The group is shown here as they set out, with Jessie Ralph as Berylune on the left.)

Or trying to. The Blue Bird‘s greatest faults are inherent in Maeterlinck’s play; this was one case where Fox might have been justified in jettisoning everything but the title. Instead, Ernest Pascal’s script made an honest effort (with moderate success) to streamline, simplify and motivate the wild excesses of Maeterlinck’s fantasy. First, merely as a practical matter, the birth order of the lead siblings was reversed, making Mytyl (Shirley) the older and Tyltyl (Johnny Russell) the younger. The size of their expedition was streamlined, with their only companions being the cat Tylette (Gale Sondergaard, right) and dog Tylo (Eddie Collins, next to her). Of Maeterlinck’s five spirits, only Light remained (played by Helen Ericson), and she served, logically enough, as the children’s guide on their quest. (The group is shown here as they set out, with Jessie Ralph as Berylune on the left.) There follows another departure from Maeterlinck. After they escape from The Luxurys, the children must pass through a great forest. Tylette, hoping to rid herself of the children and thus gain her freedom, runs ahead of them and incites the trees (represented by Edwin Maxwell, Sterling Holloway and others) to avenge themselves on the children of the woodcutter who is always chopping them down. The trees take the bait, even calling on their old enemies lightning and fire — so eager are they to destroy the children that they willingly immolate themselves in a great forest fire. Tylette, however, has outsmarted herself; trying to lure the children to their doom, she is herself burned to death, and only the courageous efforts of the loyal Tylo enables the children to escape to safety.

There follows another departure from Maeterlinck. After they escape from The Luxurys, the children must pass through a great forest. Tylette, hoping to rid herself of the children and thus gain her freedom, runs ahead of them and incites the trees (represented by Edwin Maxwell, Sterling Holloway and others) to avenge themselves on the children of the woodcutter who is always chopping them down. The trees take the bait, even calling on their old enemies lightning and fire — so eager are they to destroy the children that they willingly immolate themselves in a great forest fire. Tylette, however, has outsmarted herself; trying to lure the children to their doom, she is herself burned to death, and only the courageous efforts of the loyal Tylo enables the children to escape to safety.  …the Kingdom of the Future, where (returning to Maeterlinck’s text) Mytyl and Tyltyl find countless children are waiting to be born. In this remarkable scene, which looks like something designed by Maxfield Parrish, Mytyl and Tyltyl wander among the eager throng, so amazed at what they see that they completely forget to look for the Blue Bird. They meet a little girl who joyfully greets them by name (Ann Todd, not to be confused with the British actress of the same name), telling them that she will be their little sister, “in a year perhaps.” Then she adds sadly, “I’ll only be with you a little while.” Mytyl and Tyltyl wander among children who are preparing for what will be their calling in life. One boy proudly displays the anesthetic he will discover; another tinkers with an electric light. Still another, solitary and melancholy, tells them his destiny is to fight against slavery, injustice and inequality — but people “won’t listen…they’ll destroy me.”

…the Kingdom of the Future, where (returning to Maeterlinck’s text) Mytyl and Tyltyl find countless children are waiting to be born. In this remarkable scene, which looks like something designed by Maxfield Parrish, Mytyl and Tyltyl wander among the eager throng, so amazed at what they see that they completely forget to look for the Blue Bird. They meet a little girl who joyfully greets them by name (Ann Todd, not to be confused with the British actress of the same name), telling them that she will be their little sister, “in a year perhaps.” Then she adds sadly, “I’ll only be with you a little while.” Mytyl and Tyltyl wander among children who are preparing for what will be their calling in life. One boy proudly displays the anesthetic he will discover; another tinkers with an electric light. Still another, solitary and melancholy, tells them his destiny is to fight against slavery, injustice and inequality — but people “won’t listen…they’ll destroy me.”

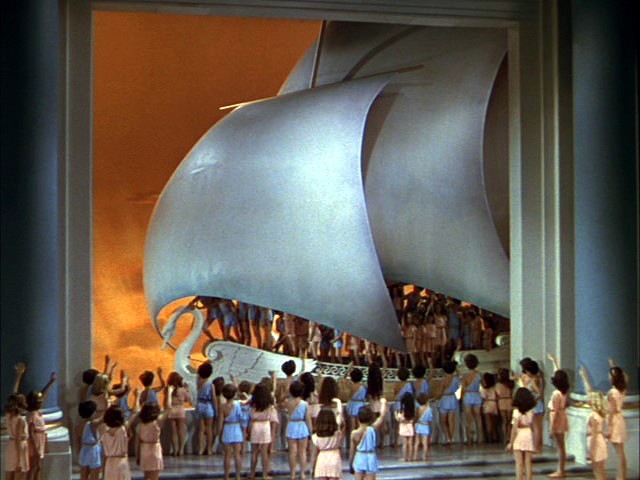

The children whose time has come board a graceful alabaster ship with silver sails and the figurehead of a swan. As the boat pulls away from the quay into a golden sea and sky, the children left behind, still awaiting their turn, bid their friends a joyous bon voyage. The departing passengers fix their eyes on the far horizon, and they sing:

The children whose time has come board a graceful alabaster ship with silver sails and the figurehead of a swan. As the boat pulls away from the quay into a golden sea and sky, the children left behind, still awaiting their turn, bid their friends a joyous bon voyage. The departing passengers fix their eyes on the far horizon, and they sing:To the world so far away

Sail we now at break of day.

Mothers waiting there below.

Do they hear us? Do they know?

From the unseen distance another song can be heard — the song of the mothers coming out to meet them.

This lovely and poignant scene in the Kingdom of the Future — straight out of Maetterlinck, but massaged by Ernest Pascal to make it less cumbersome and archly precious than it reads in the original play — is the last stop on Mytyl and Tyltyl’s journey; having visited the Future, and still not finding the Blue Bird, there’s nothing left for them but to return home.

The Blue Bird was the most expensive of all Shirley’s pictures — $1.5 million, she tells us — and it took a terrible bath at the box office, both in its original road-show engagements in New York, Detroit and San Francisco, and after going into general release at Easter. This was not, as legend would have it, because it suffered by comparison with The Wizard of Oz, but simply because The Blue Bird‘s time had long since passed. Even the 1918 silent version, lavishly produced within a decade of the play’s premiere, was a flop. (The curse repeated itself yet again in 1976, when a U.S./Soviet co-production directed by George Cukor sank like a rock. Some people never learn.)

The idea that The Blue Bird suffered by comparison with The Wizard of Oz in 1940 basically springs from the fact that it suffers by that same comparison today. Almost everyone who sees The Blue Bird nowadays can’t help seeing similarities to Oz, and of course Blue Bird can only be found wanting. There is, for starters, the black-and-white prologue, with the switch to Technicolor when the real adventure begins (although The Blue Bird never returns to black-and-white; in keeping with Mytyl’s improved outlook, the Technicolor stays to the end). Also, there’s the premise of the fantasy/dream and the look-for-happiness-in-your-own-back-yard moral. Which is ironic, considering that those elements are not found in L. Frank Baum but were swiped by Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson and Edgar Allan Woolf from Maeterlinck’s play and grafted onto their script for Oz (where they did not belong). In a real sense, MGM’s Wizard of Oz was an imitation of The Blue Bird, and not the other way around.

If viewers today were as familiar with Maeterlinck’s dreadful play as they are with Oz, The Blue Bird‘s virtues would stand out more clearly. Ernest Pascal greatly improved on the original, tightening and focusing the diffuse and rambling story, and adding two elements lacking in the play: a villain (Tylette the cat) to scheme against the children, and a champion (Tylo the dog) to come to their aid in times of danger. For all his improvements, however, Pascal never solved the dramatic problem at the heart of this fatally flawed play: there is simply no reason for Mytyl and Tyltyl to undertake this dangerous quest, and no clear reward at journey’s end to justify it. It was a shaggy-dog fairy tale when Maeterlinck wrote it, and a shaggy-dog fairy tale it remained in 1940 — and remains to this day.

The play’s reputation had lost its luster by the time Darryl Zanuck and 20th Century Fox undertook to film it, and the movie’s reviews reflected the fact. In the Times, Frank S. Nugent confessed to having “long considered ‘The Blue Bird’ complete twaddle”, an opinion which the movie did nothing to dispel: “it has about the gayety [sic] and sparkle of the first half of ‘A Christmas Carol'”. Variety’s “Flin” wrote: “Whatever freshness and imaginative charm the Maurice Maeterlinck poem play possessed a generation ago seem to have tarnished through the years…Not even Shirley Temple, in a gallery of sparkling technicolor [sic] settings, and aided by all the wizardry of the finest technical workmanship, can make it seem new.” (To be fair, Shirley didn’t have much chance. Her performance is strong, but dominated by the story rather than dominating it; as written by both Maeterlinck and Pascal, Mytyl is as much a spectator to The Blue Bird‘s goings-on as we are.) Flin correctly cited the scene in the Kingdom of the Future as “the best and perhaps complete justification for the production…However trite some other passages of ‘The Blue Bird’ seem to be, this episode is touching and fine eerie storytelling.” And in The New Yorker, John Mosher said, “All in all, I should rank ‘The Blue Bird,’ with its pretty moments and its lapses, too, somewhere halfway between the Disneys and ‘The Wizard of Oz.'” (Notice that Oz, which an earlier New Yorker review had called “a stinkeroo”, is at the bottom of Mosher’s scale.)

The opinion of The Blue Bird that would be most interesting to hear, alas, I have been unable to find: that of Maurice Maeterlinck himself. Maeterlinck landed in the U.S. later in 1940, a refugee from the Nazis storming across France and his native Belgium, and he remained here until 1947, when he returned to his home in Nice (he died at 86 in 1949). He may well have seen The Blue Bird somewhere along the line, but what he thought remains unknown. In Child Star Shirley quotes Darryl Zanuck as saying only that the playwright was consulted on the script, and that he objected to the cutting of so many of his characters, but more than that I cannot say.

Whatever Maeterlinck might have thought, The Blue Bird was a sincere effort, exerted with all the resources at 20th Century Fox’s command, and it holds up today on the strength of its production values — and, it must be said, despite the deadly weaknesses of the source material. It holds up, that is, if — and it’s a big “if” — one can watch it without making invidious comparisons with The Wizard of Oz.

But whatever I or anyone else may think today, in 1940 The Blue Bird utterly failed to find its audience — as the silent version had done in 1918, and as another version would do 36 years later. Its failure was probably Maeterlinck’s fault more than Shirley’s, but hers was the more familiar name, and the stain of the flop stuck to her. The next time out, things would not get better.

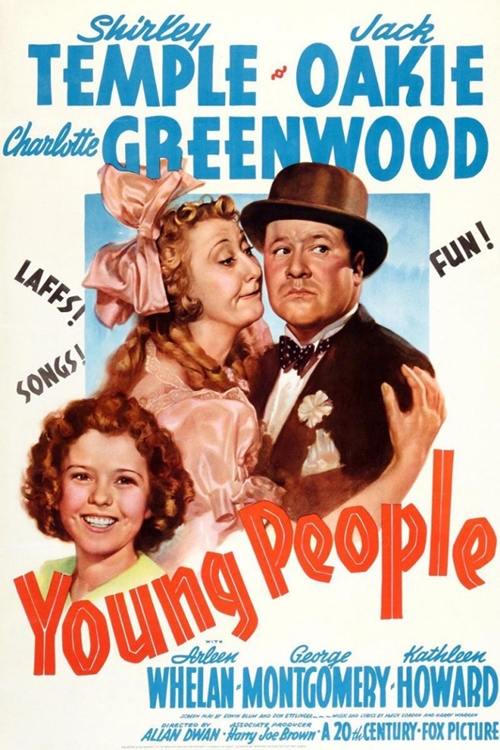

Young People

(released August 23, 1940)

As Fox had followed the lavish The Little Princess by placing Shirley in a B-western, so they followed the even more lavish The Blue Bird with an even-more-B musical. But more significantly, perhaps, by the time Young People opened in New York in August — in fact, even before Variety reviewed it in July — the picture was already a lame-duck movie. Fox chairman Joseph Schenck had announced on May 12, 1940 that the studio was “releasing” (i.e., “firing”) Shirley from the remaining 13 months of her seven-year contract. The effort of crafting vehicles for a growing child star — and of dealing with Gertrude and George Temple’s increasing objections to the unvarying parade of orphan and waif roles — had become more trouble than the diminishing box-office returns were worth. So Young People would be Shirley’s swan song at 20th Century Fox. The Blue Bird might at least have ended her career with a bang; Young People was a whimper.

Shirley’s co-stars were Jack Oakie and Charlotte Greenwood as Joe and Kit Ballantine, a husband-and-wife vaudeville team who informally adopt the infant daughter of their best friends, the O’Haras, when both parents succumb to untimely deaths.

The infant grows into Wendy (Shirley) and is incorporated into the act, now called The Three Ballantines. As Wendy approaches adolescence, Joe and Kit decide to retire from show business to a little farm they’ve bought in Connecticut, where Wendy can enjoy a “normal” life. But their brash showbiz manners scandalize the staid provincial citizens of their new home and the Ballantines become outcasts and objects of local ridicule, to the point where they are driven out of town in frustrated disgrace.

In the end, a fortuitous hurricane makes landfall near the town, Joe becomes a hero by rescuing a group of children caught out in the storm, and a tearful scolding by Wendy of the town’s leading citizens and the Ballantines’ chief tormentors (Kathleen Howard and Minor Watson) brings these bigoted small-town snobs to their senses, and the Ballantines are belatedly welcomed by their new neighbors with open arms.

In Child Star Shirley says Edwin Blum and Don Ettlinger’s script for Young People “made cheerless reading”, and it makes even more cheerless viewing. The new songs by Harry Warren and Mack Gordon (still three years from their Oscars for “You’ll Never Know” in Hello, Frisco, Hello) are lackluster, and the movie has a half-hearted romantic subplot for Arleen Whelan and George Montgomery that makes one long for the scintillating screen chemistry of June Lang and Michael Whalen in Wee Willie Winkie.

In early scenes, Young People illustrates Wendy’s start in Joe and Kit’s act by tipping in, clumsily, footage from Shirley’s “old” movies. First Jack Oakie and Charlotte Greenwood sing a chorus of Henry Kailikai’s “On the Beach at Waikiki”, followed by an extended shot of Shirley’s hula dance from Curly Top. Then, most egregiously, Oakie and Greenwood perpetrate a crass and stupid trashing of Brown and Gorney’s “Baby, Take a Bow” before the movie cuts to Shirley’s solo of the song from Stand Up and Cheer! “The film’s value,” Shirley accurately writes, “amounted to less than the sum of its parts.” Shirley deserved better, and so did Jack Oakie and Charlotte Greenwood. Hell, George Montgomery deserved better. Ironically, Young People was directed at his usual headlong pace by Allan Dwan, who years later would assert that Shirley was “over” before he undertook to direct her in Heidi. Shirley was by no means “over” in 1937, but by 1940 (and her third picture for Dwan), she certainly was.

Reviews were surprisingly indulgent — perhaps betraying a certain degree of relief that there would be no more Shirley Temple pictures for the foreseeable future. “Walt” in Variety wrote: “‘Young People’ establishes the definite spot for continuance of Shirley Temple in pictures through her adolescent and formative years. Not as a star, burdened with carrying a picture on her own, but in the groove of a featured player sharing billing and material with other top-notch artists…an above average programmer…” The Times’s Bosley Crowther added, “If this is really the end, it is not a bad exit at all for little Shirley, the superannuated sunbeam.” Even The New Yorker’s John Mosher, who rightly pegged Susannah of the Mounties as “very minor Temple”, said, “Miss Temple has obviously retired in the full tide of her powers…she shows no weariness, no slacking up, no arthritic pangs.”

If these valedictory tributes were intended even subliminally to soften the blow and let Shirley go out a winner, it didn’t work. Young People, even with its shoestrings-and-stock-footage budget, was a flop. Shirley was no longer tops at the box office — she had dropped to fifth in 1939, and by 1940 was out of the top ten — and Frank Nugent finally got the wish he expressed in his review of Wee Willie Winkie: Shirley would be a has-been at 15.

* * *

On top of that, Shirley’s first meeting with producer Arthur Freed had not gone well. Shirley says (and frankly, I believe her) that Freed said, “I have something made just for you. You’ll be my new star!”, then stepped out from behind his desk and exposed himself to her. Shirley reacted like the 12-year-old she was, bursting into a nervous laugh that didn’t sit well with the notorious casting-couch jockey, and he angrily ordered her out of his office. At almost the same moment (again, I believe Shirley), L.B. Mayer was in his office coming on to an affronted Mother Gertrude — stopping short of exhibitionism but making his intentions plain. Perhaps coincidentally, Shirley’s contract was quickly redrafted: only one picture, with no approval or creative input from Shirley or her mother.

The sole result of Shirley’s sojourn at MGM was Kathleen (’41), a “tedious, thinly plotted fable” (Variety) where, according to the Times’s Theodore Strauss, “In those wistful, winsome close-ups Miss Temple seemed to be trying to say just one thing: ‘Get me out of here!'” In any event, that’s exactly what happened.

Next, Shirley went under contract to David O. Selznick, which worked out better for her, although her days of stardom were behind her. Throughout the 1940s she would give some effective performances — Since You Went Away (’44), Kiss and Tell (’45), The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer (’47) — but Shirley was slow to learn that what had made her “sparkle” as a five-and-six-year-old could look infantile and affected in a young woman of 18 or 19. An ill-starred marriage at 17 to Army Air Corps Sgt. John Agar (who parlayed the connection into a long but inconsequential career in B movies) ended in 1950 — outlasting Shirley’s movie career by one year (her last picture was A Kiss for Corliss in 1949).

Shirley did, in time, get the hang of grown-up acting, as the host and occasional star of Shirley Temple’s Storybook and Shirley Temple Theatre (NBC, 1958-60), giving intelligent and measured performances in “The House of the Seven Gables”, “The Land of Oz”, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” and other episodes. (I remember as a child being unable to connect this adult Shirley to the curly-haired little girl in those old movies that were turning up on TV about the same time.) But by then acting was more a hobby than a calling, and when the show ran its course in two season she left it as she had left Hollywood in 1949, with never a backward glance. Ahead lay a third career — or fourth, if you count wife to Charles Black and mother to their two children, plus a daughter by John Agar — in politics and international diplomacy. And let us not forget her courageous battle with breast cancer in the 1970s, becoming one of the first celebrities to go public with her experience in that brush with death. All in all, the second half of the 20th century took her far from the tot who stood security for her movie-father’s bet on a fixed horse race and flew off on the wings of the Good Ship Lollipop. She had the grace and poise to take her long life as it came, and to make the most of it.

…However, the video still exists on YouTube. Since I am no longer able to embed YouTube videos in my posts — I still don’t know why, and I suppose I never will — I’m linking to it instead. You can see Shirley’s acceptance of the SAG award here. Skip forward to the 9:36 mark to see Jamie Lee Curtis’s introduction and Shirley’s thank-you speech.]

This was the woman who left us on February 10 of this year; long live her memory. She changed forever what it means to be a child star — mainly because, as critic Mark Steyn aptly put it, she wasn’t a “child star” at all. She was a star who just happened to be a child.

Epilogue

So there you have it, Shirley Temple’s entire career as a rising star and reigning princess during Hollywood’s Golden Age. As I said at the very beginning, while I had nothing but fond memories of Shirley, I had not seen any of these 24 pictures since I was about the age Shirley was when she made them. Several of them I had never seen at all. Seeing them — again or for the first time — was like a trip in a time machine with two stops: one at Shirley’s childhood, and another at my own.

So there you have it, Shirley Temple’s entire career as a rising star and reigning princess during Hollywood’s Golden Age. As I said at the very beginning, while I had nothing but fond memories of Shirley, I had not seen any of these 24 pictures since I was about the age Shirley was when she made them. Several of them I had never seen at all. Seeing them — again or for the first time — was like a trip in a time machine with two stops: one at Shirley’s childhood, and another at my own.

Standouts? Well, the first one that comes to mind is…

Thanks, Silver! Including that SAG clip was a last-minute choice — when I realized it was such a perfect fit that it would look like I planned it all along. It was in effect (and though Shirley herself could hardly have known it) her farewell to the world. She remained a woman of grace and poise to the end.

Thank you for posting the SAG clip. It was a perfect conclusion to your wonderful series.

You've given me lots to think about, and to re-visit, when it comes to Shirley Temple. I'm particularly interested in Louis Menand's theory about stardom lasting 3 years. I think that's true.

CW: Many thanks! Your visits and comments are always welcome. I hope you had as much fun reading this long series as I had doing it!

Wouldn't read again if a gun were put to your brother's head? Ha. You crack me up.

I only saw "The Bluebird" once, as a child, and the only thing that stayed with me was the land of the future, and those separated lovers. Haunting stuff.

I purchased the TV series on DVD a while back because I hadn't seen it in years, but had fond memories. Shirley really looked like she was enjoying herself, and that makes all the difference in the productions.

I really enjoyed reading your extensive series on Shirley. I learned so much.