The concluding chapters of London After Midnight by Marie Coolidge-Rask:

Chapter 19 – The Man in the Beaver Hat

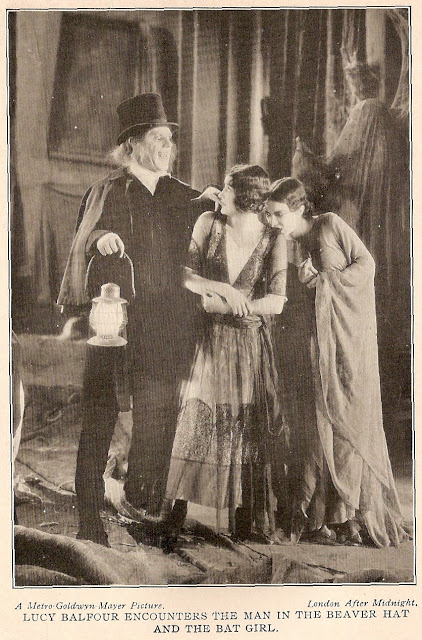

At Balfour House, the man in the beaver hat, lantern in hand, climbs the stairs to the secret room where the bat-woman hovers near the ceiling. Come down, he says, all is ready; she is on her way.

In the overgrown garden the bat-woman waits as Lucy approaches. As the two come together, a shriek like a woman’s voice rends the air. Lucy cowers, but the bat-woman soothes her: “It’s nothing. They’re awake — coming.” Lucy feels herself taken in two strong arms and carried bodily into the house. She sees that her bearer is the man in the beaver hat described by Smithson.

Lucy looks around; tears well in her eyes as she takes in the home she has not seen since her father’s death five years before. She begs the pair with her to tell her who they are.

The man in the beaver hat silences her with a gesture. Footsteps are heard outside. Suddenly there’s the crash of a shattering window and a man tumbles into the room at their feet.

Chapter 20 – Hibbs’ Madness

In Hamlin House, Hibbs dashes downstairs to where the servants cluster, roused from their sleep by the sudden hue and cry from Lucy’s room. They urgently entreat Hibbs to tell them what’s going on, but he is incoherent, raving — They’re coming! They’re all around! I go to destroy them!

The unfortunate Hibbs rummages around the kitchen, yard and outbuildings of the estate, raving about an axe and a hickory stake, the implements he must have to destroy the “vampyrs.” He finds an axe in a chopping block and sharpens two pieces of wood into stakes, muttering madly all the while. The servants watch in amazement, afraid to intervene in his maddened state. Soon he is off on his way to Balfour House on his desperate, fevered mission.

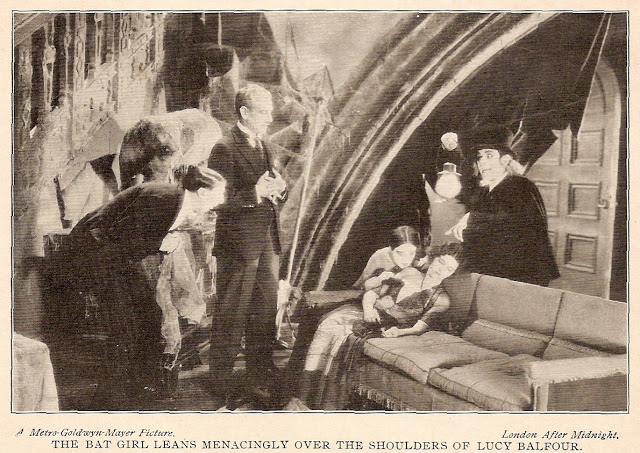

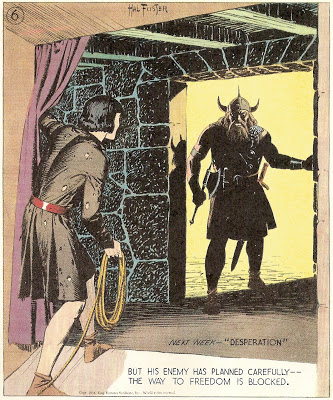

At Balfour House he lurks outside a window, his eyes wide, barely suppressing the wild beating of his heart. What he sees through the window drives him madder still: Lucy standing with the man in the beaver hat and the bat-woman. She doesn’t run, she doesn’t flee; she is in their wicked power! She must be saved before it’s too late!

Hibbs leaps through the window, falling at the feet of Lucy and the two fiends in a shower of glass. Before he can move or clear his fevered brain, creatures of unimaginable strength have pounced upon him, overwhelmed him, bound him, borne him off. Is this the end? Has he failed to save Lucy? Is he doomed to be a vampire himself?

Chapter 21 – Help from Scotland Yard

At Scotland Yard, the summons to Hamlin House has been received and a squad of constables is ready to set out. The assistant commissioner knows now that Inspector Burke’s preparations — carefully set in motion by the work of an undercover agent — are about to bear fruit.

The constables pile into a car and swiftly depart for their destination, an estate outside London. They are told that when the car is sighted there will be a signal — a siren; they are to reply with a howl, just like the other night.

As the car speeds along, they hear the siren — a long, piercing shriek like a woman’s scream. The car replies with its own special signal, a blaring electric horn like the howl of a dog. Peering into the darkness, the constables see the outline of Hamlin House straight ahead.

Chapter 22 – A Strange Conference

At Hamlin House, Colonel Yates hears the howl of a dog, just like the one the night of his and Sir James’s visit to the Balfour crypt. Looking out the window, he sees a car approaching. It must be Scotland Yard, he tells Sir James, and not a minute too soon.

As Yates and Sir James go downstairs, the butler is admitting the police, who have arrived in response to Sir James Hamlin’s request. Sir James introduces the policemen to Colonel Yates, saying he will explain the situation to them; Sir James himself is too distraught.

The colonel surveys the police detail with a military eye, apparently deciding that they will do. Quickly he summarizes the weird train of events that have led to their presence here. Now, he says, they have reason to believe that Miss Lucy Balfour is in dire peril in her former home. The police should proceed at once to Balfour House and be prepared for “instant action.”

Yates turns to Sir James; does he have his revolver ready? Sir James does. Let me see it, says the colonel. Examining the gun, he notes that it has not been fired in a long time and may not be reliable. Turning to one of the officers, he asks for a spare pistol that Sir James can carry in case the need for it arises.

Sir James, seated at his desk, tries to insist that his own revolver will do, but something in Colonel Yates’s eyes stops him. Sir James, in his highly nervous state, seems suddenly transfixed. Colonel Yates moves his hands before the man’s face but gets no response.

Satisfied, the colonel takes Sir James’s desk clock and sets the hands to eight o’clock. He places the clock before Sir James. At twenty-five minutes past eight, he tells Sir James, come to the verandah door at Balfour House.

Colonel Yates leaves with the police. Sir James, he says, will be joining them later.

Chapter 23 – From Out of the Past

Lucy is upset at what is happening to Hibbs — those men seizing him, binding him, carrying him away, saying he must be drunk. Jerry is never drunk! The bat-woman tries to calm her. Please, dear, she says, didn’t he tell you to remember your part and do it, no matter what? Yes, Lucy says, but he said he’d take care of Jerry, see that he comes to no harm. And so he will, the woman says, we all will. She turns to the man in the beaver hat. What was wrong with him? Too much excitement, the man says; he’ll be taken care of and kept out of harm’s way. But now we have to work fast.

Lucy pulls herself together. You’d better see the man in the next room, the bat-woman says to Lucy, prepare yourself. It might be a shock and you should get it over with.

Lucy parts a frayed curtain and looks into the next room at the man sitting at her father’s desk. It is a shock. The resemblance is uncanny, eerie. For a moment she feels like a little girl again, the little girl who came into this very room and found her father dead, sitting where that man is now. Lucy looks down at herself and sees that she is not that little girl at all anymore. This man can’t be her father — but he looks so like him.

Lucy prays for the strength to do what she must. She goes up to the man, who rises to greet her. They talk briefly. She answers his questions about the night she last saw her father alive. He tells her he can only imagine how difficult this is for her. He has three daughters of his own, and he hopes any one of them would feel just as Lucy does. But he also hopes that they would find the strength to do what must be done. It’s so important. “Play the role,” he says, “and make it a success.”

Chapter 24 – Metamorphosis

Lucy returns to the waiting bat-woman. The woman dresses her in a girlish white frock identical to one she had as a young girl. The woman tells her it is the same dress, that Smithson has retrieved it for Lucy to wear tonight. Again, as so often this night, Lucy is surprised; she thought she was being so clever in stealing away from Hamlin House, and Smithson knew all the time!

Colonel Yates strides into the hall with several men. One of them Lucy recognizes as one of the men who subdued Hibbs; in a flash she realizes that the other man who grappled with her sweetheart was the man who so resembles her father. Who are all these people? And who is Colonel Yates?

The man in the beaver hat removes his cloak and hands it to the colonel. Is everything ready?

Yates asks. The man says yes, handing his hat to the colonel, then removing his wig and handing that over as well. In the hat, wig and cloak, stooped over and contorting his face, Colonel Yates looks exactly like the other man — except for the absence of those spiky teeth, which he conceals by raising the collar of the cloak.

And now Smithson is there, telling Lucy how sweet she looks. I followed you to the edge of Hamlin grounds, she says, to make sure you were safe.

Colonel Yates also compliments Lucy on her appearance — just what he wanted. As he takes her by the hand and leads her toward the other room, questions swim in Lucy’s head. What is this all about? Why isn’t Sir James here? Who are these people? Who is Smithson, really? And who is Colonel Yates?

Chapter 25 – Sinister Preparations

A steady stream of commands, directions and questions comes from Colonel Yates. Where is the notary? The stenographer? He questions Lucy about the arrangement of the furnishings in the room, making adjustments as she points them out. He orders everyone to their positions. He turns to Lucy and asks if she is ready. Yes, she says, but how can going through that night again bring a guilty person to justice? All will be clear in good time, he assures her. And he reminds her, after she has said good night, not to linger but to go directly to the room where the bat-woman waits for her.

The colonel disappears behind a screen, but Lucy can just see his eyes watching through the slits between the panels. How she wishes this were all over and done. But now the house is silent, waiting. Someone is approaching along the verandah.

Chapter 26 – Sir James Pays a Call

When the desk clock reads 8:25 Sir James rises and leaves the house, pausing briefly to tell Billings, the butler, that he is going to call at Balfour House. Billings says nothing, as he was directed by Colonel Yates, merely watches Sir James go. Billings reflects on the mystifying events of the last few days, most mystifying of all being the note left by Anna Smithson, thanking him for his many kindnesses and saying, regretfully, that it is necessary for her to leave Hamlin House immediately; a baggageman will call for her luggage in the morning.

Sir James proceeds steadily to Balfour House, pausing to look around as he enters the grounds. What a fine estate he will have, he reflects, when these grounds are combined with his own.

As Sir James enters the house, the butler, Mooney, announces him. His friend Roger rises to greet him. And there is dear Lucy, that lovely little girl of Roger’s. Sir James observes with envy the affection between father and daughter as she kisses Roger good night. Lucy smiles at Sir James and extends her hand, wishing him a good night. Aren’t you going to kiss me too? Sir James asks.

Lucy’s smile vanishes. She tells Sir James she doesn’t like him when he talks like that. Then she is gone; Sir James and Roger Balfour are alone.

Chapter 27 – In Hypnosis

In Sir James’s mind, it is five years ago, the night he last saw Roger Balfour alive; the man with him is Roger Balfour; and they are alone. But the man he takes for Roger — whose real name is Drake — knows that none of those things are true. They are certainly not alone; every move they make is being watched, every word heard and taken down for the record. Now that Lucy is out of the room, there is only one person who knows how the conversation went between the two men that last night. Sir James is reliving his half of that scene; Drake must now play a very delicate game. He must deduce from Sir James’s behavior what he, as Roger Balfour, should do or say next. The slightest misstep can shatter Sir James’s hypnotic trance.

Sir James, unable to quite conceal his annoyance, tells “Roger” that he has come here tonight in a spirit of friendship to help his friend in his financial difficulties. I know about your troubles, he says, more than you realize.

Drake plays a hunch. He tells Sir James that he knows exactly the extent of his knowledge — he sees that his hunch has hit home, and continues — knows that Sir James has been stealing from him right and left, made him penniless. Now that you have me in your power, he says, what do you want?

I want Lucy, says Sir James. I have loved her since she was a baby, and I want her for my wife. You have always distrusted me, suspected me. You have called me a drug user and a sensualist, but you could never prove it.

Now Drake, with the revulsion of a father with daughters of his own, knows what Roger Balfour must have said, the only thing that could have caused events to turn out as they did. I can prove it, he says, now.

Sir James’s eyes blaze with hate as he draws his revolver. He demands these “proofs.” The other man refuses, and Sir James fires. Drake crumples to the floor, a bloody wound in his temple.

Sir James searches the desk. Those proofs, whatever Roger had, must be here, he is certain. He goes through every drawer quickly but carefully, finding nothing. The fool was bluffing. Well, now he’s dead, and good riddance. Sir James takes out his handkerchief, wipes his pistol clean, and lays it on the floor near the dead man’s lifeless fingers. Now he must escape before he is found here. He backs toward the door.

As he reaches for the doorknob his arm is seized in a powerful grip, then his other arm. Sir James struggles in a desperate frenzy, unable to break free. He hears a voice: Don’t let him get away! He’s still under hypnosis! I’m coming!

Chapter 28 – A Dramatic Awakening

As Sir James struggles, the man in the beaver hat emerges from behind a screen. Under the man’s penetrating gaze, Sir James ceases to struggle. He looks around. Balfour House! How did he get here? He sees Roger Balfour dead on the floor, exactly where he left him. But that was five years ago! Or was it? Has it all been a dream, these five years, all his patient plotting and planning to possess Lucy? All a dream during the few seconds as he made his way to the door?

It must have been! Roger had been too clever, had his men in hiding. But not clever enough; they’ve prevented my escape, but they’re too late to save his life. Sir James looks at the man in the beaver hat. Have I been asleep?

No, says the man, and neither have I. He reaches out and rips the sleeve from Sir James’s jacket. Sir James recoils from the searing pain. There! says the man. I knew I clipped you when I shot at you tonight. You thought you’d finish Hibbs with your poison needle, but I was there instead waiting for you.

Chapter 29 – Surprising Revelations

Drake rises from the floor, wiping the stage blood from his face, grateful that Sir James had been handed a doctored revolver back at Hamlin House. The man with Sir James removes his beaver hat, cloak and wig, revealing —

Yates! cries Sir James. I thought the years had changed you, but now I see you’re an impostor. You’ve set this trap to blackmail me! You’ll get nothing from me! Sir James shrieks with indignation.

“Colonel Yates” takes off his glasses, removes the subtle disguise from his face, rearranges his hair, and shows Sir James his badge: Inspector Burke of Scotland Yard. I have what I want from you, he says. I’ve spent the last three days carefully breaking down your defenses, creating a mental strain that would make you susceptible to hypnotic influence. My theory that a criminal in hypnosis, faced with the circumstances of his crime, will repeat that crime exactly — my theory has been proven correct.

Cornered, broken, trapped, Sir James crumbles and confesses all. He murdered Roger Balfour just as Burke and his crew have seen him reenact the crime tonight. He murdered Harry Balfour with a poison injection to the throat for fear that Harry would discover the proof of his wicked life that he could not find before — and worse, would take Lucy away from him. He tried to do the same to Hibbs to get him out of Lucy’s life, before Yates/Burke’s intervention sent him fleeing for his life.

The stenographer has it all. Inspector Burke orders the statement typed up. He tells Sir James that the law will see to it that every last farthing he stole from Roger Balfour will be restored to Lucy as the last survivor of her murdered family. And finally, he orders his men to examine Roger Balfour’s desk closely for evidence of a secret drawer; those proofs must be in there somewhere.

Chapter 30 – Recapitulation

Burke tells Sir James that he suspected him from the start; if only he could have acted sooner, he might have saved Harry Balfour’s life. Burke’s investigation had uncovered evidence of Sir James’s embezzlement from Roger Balfour. A former policewoman, Anna Smithson, was planted in Sir James’s household, where she uncovered evidence of Sir James’s drug use and degenerate activities. She had also overheard conversations between Sir James and Harry — no one ever notices the servants — and knew that Harry intended to remove his sister from Sir James’s influence. She had even found the vial of poison with which Sir James murdered Harry (and intended to murder Hibbs) and replaced it with a harmless liquid. The real poison is now in police hands, to be used as evidence.

Chapter 31 – Professional Pride

Inspector Burke goes upstairs to where Lucy is sitting by the bedside of Hibbs, now all but recovered from his derangement. Burke tells Lucy and Hibbs his true identity, and that he has the murderer of Lucy’s father and brother in custody. He spares her any details for the moment. She must know all in time, of course, but later, when she’s stronger.

Burke apologizes for keeping Hibbs in the dark, but it was necessary to the operation; Hibbs is not dissembler enough to have been able to play a role. Hibbs sheepishly admits that he now wishes he’d taken “Colonel Yates’s” advice and gone to bed. It would have saved everyone a lot of trouble — especially himself.

Smithson comes in to say goodbye; she will miss Miss Lucy and Mr. Jerry. She playfully scolds Burke for that “terrible tarradiddle” he made her tell about the green mist through the keyhole.

Finally come the man in the beaver hat and the bat-woman; their part in Burke’s elaborate charade is done, and now it’s back to the music halls for them. Come see us, the woman says, Mooney and Luney — Jimmy Mooney and Lunette the bat: “I fly by night an’ I sleep by day, the looniest kind of a bat!”

Afterword

So there you have it, friends: London After Midnight — a Halloween treat with a trick. If you’ve seen 1935’s Mark of the Vampire, the twist came as no surprise to you; for that matter, even in 1927 the New York Times commented that whether the ending surprised anyone would be “a matter of opinion.”

I haven’t read Philip J. Riley’s reconstruction of the picture — honestly, I can’t remember now whether it was the opportunity to buy it or the good sense that I lacked in 1987 — but I have seen the Turner Classic Movies reconstruction, and there are major discrepancies between it and the story told by Marie Coolidge-Rask. In TCM’s version, Hibbs is identified as Arthur, not Jeremiah (Jerry), and he’s Sir James’s nephew, not his secretary. (Variety’s Mori says Hibbs is Roger Balfour’s nephew, but that doesn’t make sense and is probably a mistake on Mori’s part.) Neither the TCM version nor the reviews mention the murder of Harry Balfour, or even his existence, although the illustration in the novel (see Chapter 2, “Another Mystery”) suggests Harry must have been in there somewhere. (Oddly enough, in the caption Jules Cowles, who played Gallagher the chauffeur, is identified by his own name rather than his character’s.)

Most important of all, the idea of Inspector Burke operating incognito as Colonel Yates seems to have been entirely Ms. Coolidge-Rask’s invention; in the reconstruction and both reviews Burke is openly himself throughout. He is even shown investigating the “mysterious” death of Roger Balfour and deciding it was suicide, then coming back five years later to prove it was murder — the Times reviewer pinpointed the howling illogic of that (“…Burke of Scotland Yard, the genius who wills to solve a murder mystery five years after he has declared it to be a case of suicide.”).

All things considered — and with no true copy of London After Midnight, having only Variety’s detailed recounting, the New York Times’s musings, and TCM’s version to go on — I have to say there’s good reason to believe that Marie Coolidge-Rask, despite her cumbersome way with words, made a considerable improvement on Tod Browning’s story. Once you accept the basic premise — an elaborate police sting to hypnotize a murderer into reenacting his crime — her story has its own clear logic and builds a good amount of suspense. There are many nicely creepy moments — not least the eye-opening whiff of pedophilia in Sir James’s character, which in the novel surely goes beyond what the Hays Office would have tolerated in 1927. Much of the plot as it reads must have been the novelist’s creation; there seems far too much to fit into a picture that Variety says ran only 65 minutes (TCM’s reconstruction runs 46). And the book has a good sense of pace, becoming quite breakneck as the climax approaches — just about the time Hibbs goes crazy we begin to feel as if we have, too; as Lucy’s world is turned topsy-turvy, so is ours.

I hope you’ve enjoyed Marie Coolidge-Rask’s spooky little Halloween campfire story. Have a safe and happily creepy Halloween Weekend, everyone.

What happened to Triumph over Pain once it passed through the Paramount gate is a little foggy, which could often be the case when a property bought on spec bounced around a studio full of producers and writers trying to wrestle it into a screen treatment and, eventually, a script. In his detailed introduction in

What happened to Triumph over Pain once it passed through the Paramount gate is a little foggy, which could often be the case when a property bought on spec bounced around a studio full of producers and writers trying to wrestle it into a screen treatment and, eventually, a script. In his detailed introduction in