The picture begins literally with a bang: an atomic test north of the Arctic Circle that frees the creature from suspended animation in the polar ice (audiences never tire of these stock shots of atomic explosions; they’re as fascinating now as they were half a century ago). The first man to see the beast is one of the attending scientists (Ross Elliott, in the designated role of First Expendable Victim). The second witness is the other scientist, our hero Tom Nesbitt (Swiss actor Paul Hubschmid, under the anglicized name of Paul Christian), and the movie’s first act follows Nesbitt’s crusade to prove to the skeptics around him — his military pal Col. Jack Evans (The Thing from Another World‘s Kenneth Tobey), paleontologist Dr. Thurgood Elson (Cecil Kellaway) and Elson’s assistant Lee Hunter (Paula Raymond) — that he saw what he saw. Meanwhile there are a number of unexplained occurences, including the sinking of a fishing boat whose sole survivor is dismissed as a deranged crackpot when he claims it was the work of a “sea serpent” (the sailor is played by John Ford regular Jack Pennick, his grotesque teeth either straightened or, more likely, replace by dentures).

Another of these occurences is the destruction of a lighthouse on the coast of Maine, an episode straight from the Ray Bradbury short story that (according to the credits) “suggested” Lou Morheim and Fred Freiberger’s screenplay. And this is as good a place as any to discuss the movie’s origins.

The story first appeared in the June 23, 1951 issue of the Saturday Evening Post as “The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms”. It was later antholgized in Bradbury’s collection The Golden Apples of the Sun, its title changed to “The Fog Horn”, and it is by that name that it’s been known ever since. My guess is that “The Fog Horn” was Bradbury’s original title and that the Post editors gave it the other one; it sounds about like the magazine’s style in those days. Since the movie’s original working title was Monster from the Deep, I’m also guessing that Dietz first hired Harryhausen for the project, then came across Bradbury’s story and decided to incorporate it, and to appropriate its title, as an afterthought. If so, then it must have been a pretty early afterthought, because the movie adopted not only the title…

…but, with modifications, the look of the monster itself, as you can see by comparing the frame from the movie above with this illustration from the magazine. In the movie the beast is identified as a “rhedosaurus”, a species that does not exist in the annals of paleontology. It’s fun to believe that the first two letters of the beast’s name stand for the “RH” of Ray Harryhausen (Harryhausen denies it, but I think perhaps he doth protest too much).

And doesn’t the title The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms have a great ring to it? Much better than Monster from the Deep. Scientifically, it’s nonsense; a fathom is a measure of nautical depth, six feet — or, at the rate of 20,000, 22.7 miles. The beast from 22.7 miles down, in an ocean (the Arctic) that never gets deeper than 3.4 miles? Even the deepest spot on earth, the Mariana Trench in the Pacific, is only 6.9 miles. But never mind, The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms sounds awe-inspiring, primeval, almost Shakespearean; kudos to that Saturday Evening Post editor for coming up with it.

The Beast‘s money scene is the monster’s invasion of New York (not far, Kellaway’s Dr. Elson tells us, from where the only rhedosaurus fossils have ever been found), and the Big Apple hasn’t had it so bad since King Kong came to town. In fact, compared to the rhedosaurus, Kong’s rampage looks comparatively benign: a quick shot of newspaper headlines tells us there are 180 known dead, 1,500 injured, and damages estimated at $300,000,000 (and that’s in Eisenhower dollars; add a zero or two to get a current equivalent). “The worst disaster in New York’s history!” shouts a radio newsman, as the National Guard is trucked into town, hospital emergency rooms are overwhelmed, and New Yorkers cower behind their doors, afraid even to look out the window.

This sequence includes a moment that nobody who saw it in the 1950s has ever forgotten. An unbilled Steve Mitchell, playing an NYPD patrolman, bravely stands his ground, even advances on the beast, using nothing but his .38 caliber police revolver…

…only to be plucked screaming off his feet in the monster’s teeth and downed in one quick gulp. It’s a grisly death Harryhausen had practiced on a classmate in one of his experimental films as a teenager, and I’m sure Steven Spielberg had it in mind 40 years later when he had that T-rex snatch the cowering lawyer off the toilet in Jurassic Park. But in Beast it’s a moment of noble sacrifice (the cop is not made to look reckless or foolish), and our sad knowledge of September 11 makes it even more poignant when viewed today.

As the rhedosaurus wreaks its havoc on Manhattan, Harryhausen manages to fit in a nice little tribute to his mentor Willis O’Brien. As the beast claws at this building, ultimately reducing it to rubble (and annihilating an unlucky group of extras in the alley beyond)…

…the shot mirrors this one from The Lost World (’25), in which O’Brien’s brontosaurus deals out the same fate to a building in London (albeit with less explicit loss of life).

Ultimately, the rhedosaurus is cornered at Coney Island, wounded and enraged by a lucky shot earlier in the evening from a National Guard bazooka. Worse, the nuclear test that freed it from its icy tomb seems to have turned it into a carrier of some virulent radiation sickness; soldiers exposed to the manhole-size drops of blood falling from its wound have been keeling over without warning left and right. Tom Nesbitt announces that (for reasons the script doesn’t slow down to explain) the only way to stop the creature is to shoot a radioactive isotope into its wound “and destroy all that diseased tissue.” So Nesbitt and an Army marksman (an amazingly youthful Lee Van Cleef) don their haz-mat suits and ride to the top of the rollercoaster for a clear shot, and at last the monster’s number is up.

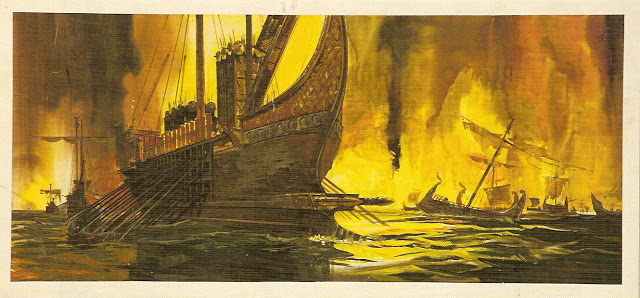

But not without a fight. Before the monster’s death throes have run their course, the rollercoaster becomes an inferno of flames (Nesbitt and the marksman make it safely to the ground), and the rhedosaurus gets a funeral pyre to match its gargantuan size. Harryhausen says that Eugene Lourie once accused him of having his monsters die “like a tenor in an opera”, and that’s what this one does:

Once The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms was in the can, Jack Dietz tucked it under his arm and went shopping for a distributor. Eventually, he sold it to Warner Bros. for (according to Harryhausen) about $450,000. That represents a very tidy profit over his original investment, but with a fly in the ointment: Harryhausen says the picture went on to make “millions” for Warners — $5,000,000, as a matter of fact, at a time when that was real money; nearly twice as much, for example, as Bwana Devil, the surprise hit of ’53 that kicked off the first short-lived 3-D craze. More, too, than other 3-D hits of the year, like Charge at Feather River, It Came from Outer Space and Kiss Me, Kate (not quite as much as House of Wax, though, but pretty close, and without the novelty of 3-D).

Warner Bros. profited from

Beast in another way as well. Barely a year (in fact, 371 days) later, the studio released its own homemade variation:

Them! Warners knew a good thing when they had it, and they stuck close to the formula. Once again, nuclear testing unleashed a horrible freak of nature (this time, giant mutant ants), a major city came under attack (Los Angeles), and a beloved old character actor was along to play the movie’s senior scientist (Edmund Gwenn, in a role very much like Cecil Kellaway’s in

The Beast). Other animals, insects, arachnids, even humans, would stumble into the atomic oven and thunder out their warnings of Things Man Was Not Meant to Meddle In, and plenty of them are on view in this blogathon.

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms led the way, and proved there was gold in them thar radioactive hills.

After

The Beast, Ray Harryhausen was on a roll:

It Came from Beneath the Sea,

20 Million Miles to Earth,

Earth vs. the Flying Saucers. But in 1958 he, producer Charles Schneer and director Nathan Juran made a picture that represented an orders-of-magnitude leap forward on the keen-and-neat-o scale.

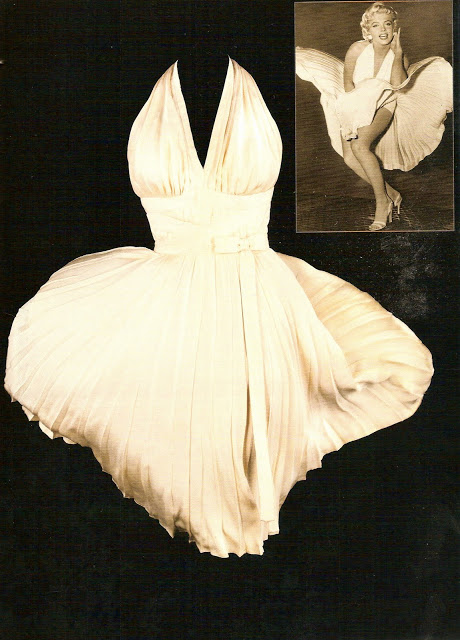

Partly because it was in georgeous, eye-popping Technicolor. But there was also the sheer volume of its visual effects. The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms runs an economical 79 minutes, and its effects shots add up to (surprisingly) only 7 minutes 5 seconds — or 8.9 percent of the running time. The 7th Voyage of Sinbad runs 88 minutes, with 17 minutes 27 seconds of effects — 19.8 percent. More monster-time, but more monsters, too; more, in fact, thanall Harryhausen’s previous pictures put together. The Beast, It Came from Beneath the Sea and 20 Million Miles to Earth each had a single animated creature. But Sinbad had more than you could shake a scimitar at.

This one, for example. It’s the first beast we see, not seven minutes in — the collossal Cyclops, encountered when Sinbad (Kerwin Mathews) and his crew make an unscheduled stop at the uncharted island of (appropriately) Colossa.

Sinbad has been blown off his course as he sailed home to Bagdad after a diplomatic mission to the Sultan of Chandra. There he not only averted war between Bagdad and Chandra, but wooed and won the hand of Princess Parisa (Kathryn Grant), daughter of the Sultan.

As Sinbad and his crew come ashore seeking food and water, the Cyclops appears suddenly, pursuing a man in a black gown who is calling for help. This is the magician Sokurah (Torin Thatcher), a crafty and devious man who, once they are all safely back aboard the ship, arouses Sinbad’s suspicions.

Sokurah tries to bribe Sinbad to return at once to Colossa, to retrieve a magic lamp that the Cyclops has stolen from him. He appeals to Sinbad’s greed, telling him that the Cyclops is a hoarder of treasure, not only Sokurah’s lamp, and that Sinbad and his crew can claim any amount of the treasure as plunder — once Sokurah has his lamp back. But Sinbad’s first duty is to his Caliph, and to keep the Princess safe from harm — not only for the sake of his love for her, but for the sake of peace between Bagdad and Chandra.

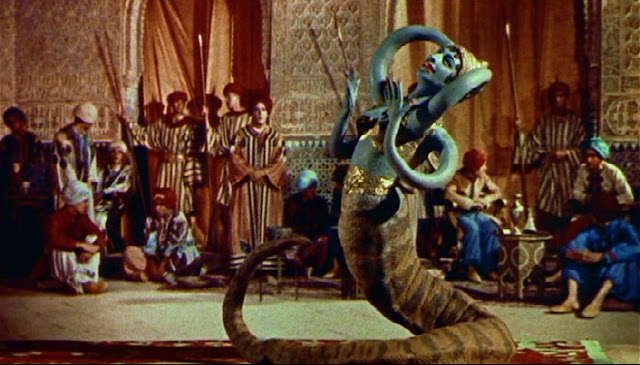

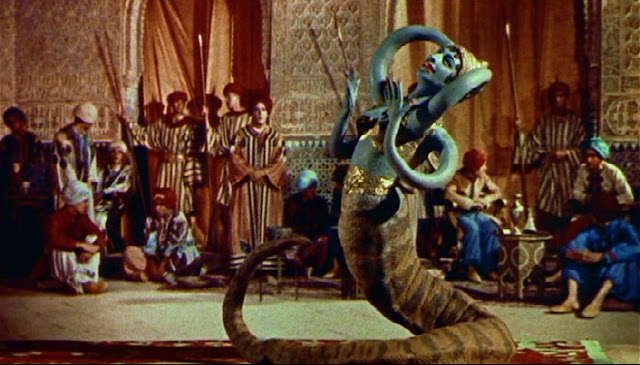

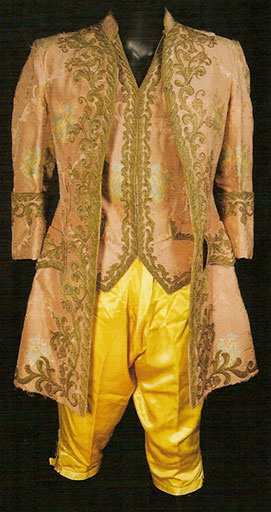

In Bagdad, Sokurah performs wonders for the Caliph and the visiting Sultan of Chandra, including (briefly) joining the Princess’s serving woman and a serpent into this amazing, sinuous creature before returning the servant (and presumably the snake) back to their original bodies. Sokurah attempts to wheedle the Caliph into fitting out an expedition to return him to Colossa, but the Caliph remains firm; his mind is not to be changed even by such clever tricks as these. Perhaps, Sokurah mutters ominously, an even greater demonstration of my powers is called for.

The next morning, Sokurah has done his work. Princess Parisa is discovered in her bedchamber, alive and well but shrunken to the size of a tiny doll. The Sultan, outraged and grieving, vows to reduce Bagdad to ashes to avenge this insult to his daughter. His hand is stayed only when Sinbad seeks out Sokurah and gets the sorcerer to admit that he can return the Princess to her normal size — but only with a potion using the eggshell of the giant bird, the Roc, which is found (of course) only on Colossa. So the magician has at last extorted his expedition after all, to be led by Sinbad himself. But Sinbad fears — knows — that Sokurah can’t be trusted, and that he will have to be kept a wary eye on.

The 7th Voyage of Sinbad was part of a movie vogue that was petering out by the time it went into production in 1957: the Arabian Nights adventure. The genre — at least this incarnation of it — had begun in 1940 with the phenomenal success of the marvelous, magical The Thief of Bagdad from Alexander Korda’s London Films. It spurred a flood of similarly-themed adventures throughout the ’40s — most noticeably in a series of campy Technicolor romps from Universal starring Jon Hall and Maria Montez (“the King and Queen of Technicolor”), but cropping up in other unexpected places, like MGM’s Kismet (1944) with Ronald Colman and Marlene Dietrich, and Warner Bros.’ update of The Desert Song (1943), with Dennis Morgan as a burnoose-clad freedom fighter battling Nazis in war-torn Morocco.

It was during this time that Ray Harryhausen first conceived the idea of a Sinbad adventure, and he drew a series of preliminary sketches of the kind of thing he had in mind. There had been Sinbad the Sailor in ’47, but that was a conventional swashbuckler with Douglas Fairbanks Jr. and Maureen O’Hara; Fairbanks spoke of battling Rocs and Cyclops and dragons, but what the movie showed was far more mundane. Harryhausen’s idea was to make a movie filled with the things Fairbanks’s Sinbad only talked about.

Unfortunately for him, in 1955, RKO Radio Pictures mogul Howard Hughes, while he was in the process of running his studio into the ground, produced Son of Sinbad with Dale Robertson, which rightly laid a Roc-sized egg at the box office. Wherever Harryhausen turned, the answer was the same: “sailor pictures” are dead, just look at what happened to Son of Sinbad.

But producer Charles H. Schneer — with whom Harryhausen had already made It Came from Beneath the Sea, Earth vs. the Flying Saucers and 20 Million Miles to Earth — believed.He even wanted to shoot in color, about which Harryhausen was dubious. Harryhausen had just developed a process — later dubbed Dynamation — with which he could combine live action and special effects animation on the same strip of film negative without having to resort to costly and time-consuming matching of negatives in the lab (the animation alone was costly and time-consuming enough), and he wasn’t sure it would work for color as well as for black-and-white. But Schneer had him shoot some tests to make sure, and they were on their way.

The picture was shot in Spain (another point on which Schneer and Harryhausen were pioneers; in the 1960s many Hollywood epics, and Sergio Leone’s Italian spaghetti westerns, would also be shooting there), and Schneer was as resourceful with a budget as Jack Dietz had been. He even secured permission to shoot in the Alhambra in Granada, giving him and director Nathan Juran access to lavish sets at a fraction of the cost of building them. (Later crews were less respectful than Sinbad‘s, and now the Alhambra is off-limits to movie production.)

The 7th Voyage of Sinbad is a movie of endless wonders, thrills and delights. Time and again, Sinbad and his crew (and the tiny Parisa, helpless in her little doll’s cabinet) have barely vanquished or escaped from one fantastic creature before they are set upon by another — like this angry two-headed Roc, who takes exception to Sinbad plundering her eggs for the shell that will help restore the Princess…

…or the Cyclops again, preparing to barbecue Sinbad’s friend Harufa (Afred Brown) for his dinner…

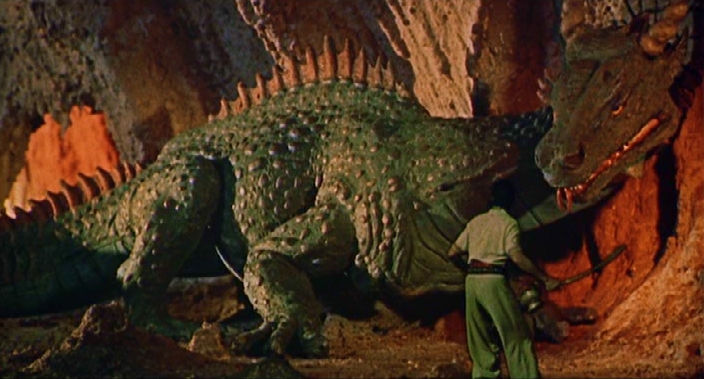

…or the fire-breathing dragon guarding Sokurah’s underground castle, where Sinbad goes to rescue Parisa after Sokurah has betrayed them all and spirited the Princess away…

…or most awe-inspiring of all, the skeleton Sokurah brings to life and arms with sword and shield to duel Sinbad to the death. This scene was such a tour de force that Harryhausen couldn’t resist outdoing it five years later in Jason and the Argonauts, when the hero and his friends battle a cadre of no fewer than seven deadly skeletons.

The Arabian Nights adventure came in in a blaze of glory with The Thief of Bagdad, and after years of diminishing returns it went out in a blaze of glory with The 7th Voyage of Sinbad. There would be other movies in the genre — Harryhausen himself would make sequels, and pretty good ones, in 1973 and ’77 — but these two movies, each in its own distinct way, are the unassailable peaks of the form, never equaled, much less surpassed.

The secret to the success of both movies, of course, is that they aren’t really “Arabian” at all. What they are, in fact, is Arabesque — an elaborate fantasia on the mere idea of the tales of Scheherezade, decorated with the filigree of genies, evil wizards, fabulous monsters, dauntless heroes and pure, chaste maidens in mortal peril.

Oh, and let’s say a word about that genie, Barani — the one in the magic lamp so desperately coveted by the wicked Sokurah. He’s played by 12-year-old Richard Eyer, one of the most ubiquitous child actors of the 1950s, who had already made his mark in such movies as Come Next Spring, The Desperate Hours and Friendly Persuasion, and on countless television series. His talent wasn’t spectacular, but it was real, and he brought a down-to-earth conviction to any role he played; he was a real kid, not a show-off Hollywood brat. And even though he was about as “Arabian” as a Fourth of July picnic, casting him in The 7th Voyage of Sinbad was an act of sublime genius. Here, right in the middle of all these monsters and wizards and princesses, was a boy just like you or me — only he could do magic! I’ve never seen this commented on before, but I think Richard Eyer’s presence is crucial to the success of Sinbad, as much as Torin Thatcher’s ability to embody pure wickedness or Kerwin Mathews’s uncanny way of really seeing all the creatures that won’t be tipped into the scene with him until months after shooting has wrapped. Richard Eyer gives the kids in the audience — like my brothers, our friends and me — something they can identify with and hold on to amid the wonders going on before their wide and staring eyes. Richard Eyer had a very special place in my heart after I saw The 7th Voyage of Sinbad.

In using the heading “Lost & Found” for this post, I don’t mean to suggest a “lost” film in the sense that historians and archivists have come to mean it. I mean a movie that was once readily available — at least on TV, and in my neighborhood, in the days of local stations’ film libraries and syndication packages — but that now seems to have vanished entirely except for the occasional 16mm print or bootleg video.

In using the heading “Lost & Found” for this post, I don’t mean to suggest a “lost” film in the sense that historians and archivists have come to mean it. I mean a movie that was once readily available — at least on TV, and in my neighborhood, in the days of local stations’ film libraries and syndication packages — but that now seems to have vanished entirely except for the occasional 16mm print or bootleg video. Night Has a Thousand Eyes originated as a novel by Cornell Woolrich, one of the more unusual creeps in the history of Hollywood (where creeps have never exactly been an endangered species). Born Cornell George Hopley-Woolrich in 1903, his parents separated when he was little. He lived with his father in Mexico until he was 12, then moved to New York to live with his mother — which, except for one brief interval, he did for the rest of her life. He dropped out of Columbia when his first novel Cover Charge promised success as a writer.

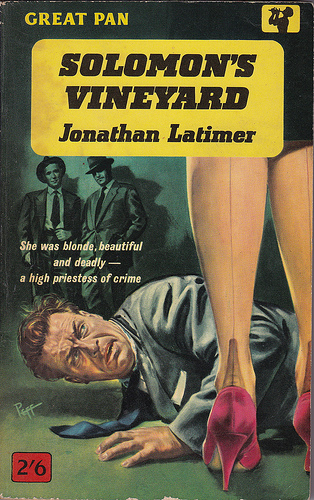

Night Has a Thousand Eyes originated as a novel by Cornell Woolrich, one of the more unusual creeps in the history of Hollywood (where creeps have never exactly been an endangered species). Born Cornell George Hopley-Woolrich in 1903, his parents separated when he was little. He lived with his father in Mexico until he was 12, then moved to New York to live with his mother — which, except for one brief interval, he did for the rest of her life. He dropped out of Columbia when his first novel Cover Charge promised success as a writer.  Night Has a Thousand Eyes was published in 1945 under one of Woolrich’s pen names, George Hopley (his two middle names); later, in this ’50s-vintage paperback, under his other one, William Irish. But in 1948, when Paramount and director John Farrow filmed the novel, the screen credits named Cornell Woolrich as the novel’s author.

Night Has a Thousand Eyes was published in 1945 under one of Woolrich’s pen names, George Hopley (his two middle names); later, in this ’50s-vintage paperback, under his other one, William Irish. But in 1948, when Paramount and director John Farrow filmed the novel, the screen credits named Cornell Woolrich as the novel’s author. Rather than plot or style, what Woolrich’s novel has is mood — in spades, and maybe even to a fault — the chilling sense of being in the grip of some insensate force, powerless to resist. If Woolrich did happen to swing by New York’s Paramount Theatre when the movie opened there in October 1948, he might have noticed that that mood is preserved on the screen, even as his entire story and most of his characters are jettisoned.

Rather than plot or style, what Woolrich’s novel has is mood — in spades, and maybe even to a fault — the chilling sense of being in the grip of some insensate force, powerless to resist. If Woolrich did happen to swing by New York’s Paramount Theatre when the movie opened there in October 1948, he might have noticed that that mood is preserved on the screen, even as his entire story and most of his characters are jettisoned. In the movie Tompkins becomes John Triton (Edward G. Robinson), a vaudeville and nightclub mentalist with a phony mind-reading act. Or rather, that’s what he was some twenty-odd years ago, as he describes things to us in flashback. As he plies his act in theaters and saloons from town to town, he finds himself — and he’s not even sure exactly when it started — getting genuine flashes, glimpses into the future: the winner in a horse race, the son of an audience member who is playing with matches at home and about to set fire to the house, an investment opportunity that will pay off.

In the movie Tompkins becomes John Triton (Edward G. Robinson), a vaudeville and nightclub mentalist with a phony mind-reading act. Or rather, that’s what he was some twenty-odd years ago, as he describes things to us in flashback. As he plies his act in theaters and saloons from town to town, he finds himself — and he’s not even sure exactly when it started — getting genuine flashes, glimpses into the future: the winner in a horse race, the son of an audience member who is playing with matches at home and about to set fire to the house, an investment opportunity that will pay off.

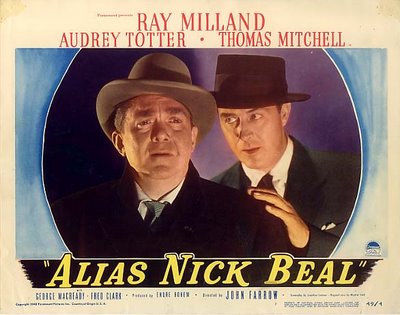

Night Has a Thousand Eyes is a specimen of a rare subgenre: supernatural noir. There aren’t many examples of that; parapsychology, the “spirit world”, and such things are not to be easily grafted onto the gritty, cynical urban landscapes of movies like Laura and Double Indemnity. But John Farrow, Jonathan Latimer and producer Endre Bohem would do it again the following year in their next picture together, just a few months after finishing this. The result would be a neglected classic — forgotten now but, once seen, unforgettable. I’ll write about that one next time.

Night Has a Thousand Eyes is a specimen of a rare subgenre: supernatural noir. There aren’t many examples of that; parapsychology, the “spirit world”, and such things are not to be easily grafted onto the gritty, cynical urban landscapes of movies like Laura and Double Indemnity. But John Farrow, Jonathan Latimer and producer Endre Bohem would do it again the following year in their next picture together, just a few months after finishing this. The result would be a neglected classic — forgotten now but, once seen, unforgettable. I’ll write about that one next time.