The 50th Anniversary Ultimate Collector’s Edition of Ben-Hur is out. Mine arrived last week, number 13,192 of 125,000 — so be warned: If you want your own copy, you’ve got only 111,808 more chances to buy it. As 50th Anniversary Editions go, this one is a little tardy, by nearly 22 months; the picture premiered in New York (at the Loew’s State on Broadway) on November 18, 1959.

New York had a lot more daily newspapers in those days, and movie reviews were a lot more important, especially to a roadshow attraction like this that couldn’t count on a big ten-jillion-screen opening weekend to make most of its money. A picture like Ben-Hur had to have “legs”, and for that the New York critics were as important as they were to any first night on a Broadway stage. If the suits at MGM had been worried about the critics, they were breathing a lot easier by the afternoon of November 19. The chorus of praise was deafening: “a remarkably intelligent and engrossing human drama” (New York Times); “squirms with energy” (Tribune); “a classic peak” (Post); “stupendous” (Daily News); “extraordinary cinematic stature” (Journal-American); “massive splendor in overwhelming force roars from the screen” (World-Telegram).

If you agree with all these encomia, you might want to read no further, because I don’t agree and I never have. As far as I’m concerned, of all the lousy movies that have won the Oscar for best picture (a very crowded field), Ben-Hur may be the lousiest of the lot. (“Well, if you feel that way about it, why did you shell out 45 smackers for a deluxe boxed Blu-ray?” Good question; all I can say is, just as not every good movie is important, not every important movie is good.)

Let me remind you (if you’re old enough to remember) or tell you (if you’re not) how moviegoing has changed in 50 years. Forget home theaters, forget cable or satellite TV, forget Tivo or Internet streaming, forget even multiplexes. What they now call “platforming” wasn’t a rare distribution strategy in those days, it was how all movies were handled. A movie would open in the big cities first — New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, maybe San Francisco, Atlanta, Washington DC, St. Louis and a few others. Maybe in two or three theaters in the big cities, but probably in only one (and all theaters had only one screen). After its first run, the movie would filter down to smaller theaters in the big markets and bigger theaters in the smaller markets. If your hometown was small enough and far enough from a major market, you could have months of mounting anticipation before you had a chance to see the movie everybody you didn’t know was talking about.

And absolutely forget about waiting till a movie turned up on HBO or Netflix. You’d have one chance to see it; even then it might play only three or four days and be gone. If you couldn’t catch it those days, you could hope it would be held over or brought back. Maybe it would, maybe it wouldn’t. If not, you could watch for it at your local drive-in or theaters in a neighboring town, maybe in vain. That was moviegoing in the 1950s.

This dynamic was intensified in the case of roadshow attractions. I don’t mean just the Cinerama movies, which were a special case all to themselves. I mean movies like Oklahoma!, Around the World in 80 Days, The Ten Commandments, South Pacific; they might play a year or more in metropolitan areas before going into general release (“Now at popular prices!”). Where we lived in Northern California, the nearest big city was San Francisco; I had friends whose parents took them down there to see Oklahoma! and Around the World, but my family never went in for that; I just had to wait. (I didn’t see Oklahoma!, for example, until 1961, and only then because we moved to Sacramento in the summer of 1960.)

If we hadn’t made that move, it might have been at least another year before I got to see

Ben-Hur — that’s the kind of business it was doing; general release still looked a long way off. But

voila! —

Ben-Hur was playing at Sacramento’s most opulent picture palace, the Alhambra. By that time, as I’ve written

here and

here,

Ben-Hur was more than a movie; it permeated the culture — every newspaper, every magazine, every comedy routine, every conversation. Myself, I had already gotten a set of four toy

Ben-Hur chariots for Christmas and played them to pieces. I had even found time to read the book — no small undertaking for a kid, believe you me. One of the Alhambra’s ticket outlets was the Sears Roebuck credit office, and they had a 6-foot-tall cutout of this logo mounted over the counter. That cutout alone was awesome, breathtaking; it was like gazing up at a cardboard Mt. Rushmore. (I wonder if any of those cutouts survive.) I wheedled the astronomical $3.00 admission price from my parents, and one Sunday in September I finally took my seat to have (as the posters promised) The Entertainment Experience of a Lifetime.

Well.

As it turned out, this milestone in the march of Western Art was only a movie after all. And to my bewildered surprise, as I sat there in the throng — the Alhambra held 2,500 and it was jam-packed to the last row of the balcony — I found a startling thought running unbidden through my head: “This movie…isn’t…very…good.”

The first stirrings of disappointment came during the pre-title sequence showing the birth of Jesus, with the Wise Men tromping up and plopping their gifts down. It looked as awkward to me as a Nativity Scene enacted by a Sunday School kindergarten…

…with a Star of Bethlehem as tacky as a dimestore Christmas card or the picture on a gas station calendar. I didn’t really know the meaning of the word “sublime” at that age, but I understood the concept, and I knew that just about everybody had promised me something like that in Ben-Hur. Well, it hadn’t really started yet; maybe things would get better.

They didn’t. By the time of the “great sea battle” — nearly an hour and a half later — I had about decided somebody was pulling a fast one. I was twelve years old and thinking, “How fake!” Maybe it was the huge screen, but these boats looked like bathtub toys. Howard Lydecker (though I didn’t know his name at the time) had done a better job on Sink the Bismarck!, and with probably one-tenth the money MGM spent on this.

I wish now I had thought to eavesdrop on the lobby-talk at intermission, but I didn’t, so I don’t know how Ben-Hur was going over by the halfway (actually, about two-thirds) mark. But I remember what I was thinking: “Are they really falling for this?” I felt like the boy in Hans Christian Andersen suddenly blurting out that the emperor had no clothes. But I didn’t blurt anything; I kept my thoughts to myself. I was just a kid, what the heck did I know?

I left the Alhambra Theatre that evening sadder, wiser, and four hours older, with a valuable lesson: Don’t believe everything you hear.

Seeing the picture again and again over the years brought into focus things that I hadn’t specifically noticed the first time, but that I could see had added to my general disappointment, like the solemn, leaden pace, with pregnant pauses between and during the speeches, each pause several weeks more pregnant than the last. Or the dull non-performance of Haya Harareet as Esther, Judah Ben-Hur’s love interest. Harareet had little screen presence and less chemistry with Charlton Heston (for contrast, see Heston and Sophia Loren in El Cid), and after Ben-Hur Harareet’s career went precisely nowhere. (For that matter, that’s where it went even during Ben-Hur.)

On a related side-note, we’ve all heard Gore Vidal’s story about how he saved the Ben-Hur script by writing in a homoerotic subtext between Heston’s Ben-Hur and Stephen Boyd’s Messala, a story Vidal continues to tell despite on-the-record denials from both Heston and director William Wyler before they died. Well, maybe it’s there and maybe it isn’t; by the time Vidal started talking about it, Stephen Boyd was no longer around to give his take on it. More obvious to me — now, I mean, not in 1960 — is the same subtext between Ben-Hur and the Roman soldier Quintus Arrius (Jack Hawkins) during the rowing drill in the galley; Arrius gazes intently through hooded eyes at the half-naked Judah as the hortator steps up the drumbeat and Judah strokes, strokes, strokes, faster and faster. Maybe Vidal wrote that too, and maybe Hawkins played it, I don’t know. My point is that all this talk about real or imagined homoerotic undercurrents in Ben-Hur is possible at least in part because plainly, there’s absolutely nothing going on between Charlton Heston and Haya Harareet.

But back to my train of thought. When I saw Ben-Hur in September 1960, I had already read and enjoyed the book, so I never for a minute believed that the movie had simply gone over my 12-year-old head. Here was a picture that, as I saw it, was mediocre at best, yet it had critics everywhere flying into transports of ecstasy. Even the reliably hypercritical Time Magazine said that the script “sometimes sing[s] with good rhetoric and quiet poetry.” (Really? Somebody quote me a line or two of that singing, quiet poetry. I dare you.)

To me it was a paradox, one I mulled over intermittently for years. Finally I came up with…I can’t really call it a theory, exactly; it’s more a hypothesis. No doubt it’s a gross over-simplification, but I think it’s worth trotting out and looking at.

And now this brings me to what I mean by the title of this post: “The 11-Oscar Mistake”. I don’t mean to say that giving Ben-Hur 11 Oscars was a mistake (although I think it was). What I mean is that there was a serendipitous mistake in the picture itself that wound up making it a huge hit and winning it 11 Oscars.

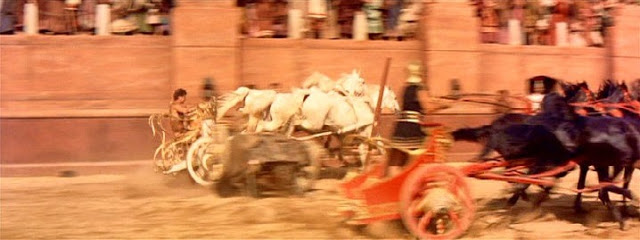

The mistake happened during shooting of the one sequence where Ben-Hur unquestionably delivers the goods: the chariot race. It’s 8 min. 38 sec. of pure visceral excitement, and to get the full pulse-pounding impact of it you really had to see it in a huge theater on an 80-foot screen with 2,499 other people who were just as edge-of-the-seat excited as you were. (When was the last time you saw any movie with thousands of strangers? I’ll bet it’s been a while.)

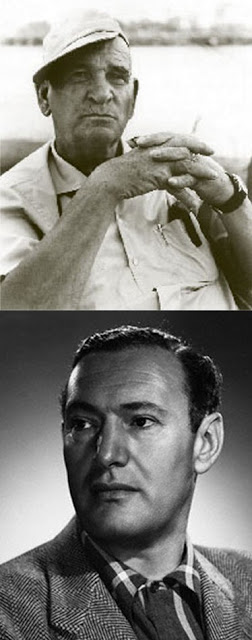

The chariot race was the work of second unit directors Enos Edward “Yakima” Canutt and Andrew Marton (finally assembled by editors John D. Dunning and Ralph E. Winters). Yakima Canutt is far and away the greatest and most famous stuntman who ever lived, with a career spanning 60 years from Foreman of Z Bar Ranch in 1915 to Breakheart Pass in 1975 (when he was 80). He all but invented the craft of movie stunt work, and he literally invented any number of safety devices to minimize the inherent dangers of the job. As either stunt performer, stunt coordinator, second unit director, producer or actor (sometimes wearing more than one hat on the same picture) he racked up nearly 500 titles in his filmography. (He also has the distinction of being the first man to go before the cameras in Gone With the Wind, doubling Clark Gable in the burning-of-Atlanta sequence.) For Ben-Hur Canutt selected and trained both the horses and drivers for the race.

Andrew Marton’s career was almost as long as Canutt’s (from 1927 to ’77), most often as director (King Solomon’s Mines [’50], The Longest Day, Crack in the World, Clarence the Cross-Eyed Lion) but also as second unit director on many major pictures (The Red Badge of Courage, A Farewell to Arms [’57], Cleopatra [’63], Catch-22, The Day of the Jackal). On Ben-Hur Marton was in charge of the crew behind the camera while Canutt handled the human and animal crews in front of it.

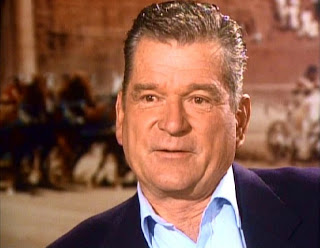

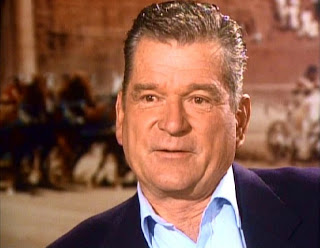

Doubling for Charlton Heston in the race’s more hazardous shots was Yakima Canutt’s 21-year-old son Joe (shown here in a 1994 interview). Heston had worked for weeks with the second unit crew to master driving his own chariot, adding one horse at a time until he was driving a full team of four. By the time it came to shooting, Joe Canutt said, Heston was as good a charioteer “as any man in the business”, and he’s in the chariot for quite a bit of the race. But as ever the case in Hollywood, MGM wasn’t about to let their star take any foolish chances, and that’s where Joe came in.

It was during this training that one of Heston’s best-known anecdotes happened. You’ve probably heard it, but it bears repeating here in light of how things turned out. One day Heston turned to Yakima Canutt and said, “Y’know, Yak, I feel pretty comfortable running this team now, but we’re all alone here. We start shooting this sucker in ten days. I’m not so sure I can cut it with seven other teams out there.” “Chuck,” said Canutt, “you just make sure y’stay in the chariot. I guarantee yuh gonna win the damn race.”

Keeping Judah Ben-Hur in the chariot turned out to be a pretty near-run thing. Canutt senior had worked out a number of “gags” to punctuate the race with excitement — wheels disintegrating, chariots crashing, Roman guards and chariot drivers (actually dummies) getting trampled and run over, and so forth. One of them called for Joe Canutt, doubling Heston, to drive his chariot over the wreckage of two others — actually a short ramp placed in his path and blocked from camera sight by one pile of debris. In concept it was a pretty simple stunt, not particularly designed to stand out in the mayhem.

Joe worked long and carefully with his team before the shoot. He took the horses up and over the ramp one at a time, then in pairs harnessed together, then threes, then all four, then the four harnessed to an empty chariot, and finally all four, the chariot and Joe. At last everybody, human and equine, was comfortable with the stunt.

Here’s how the sequence was planned, shot by shot — each shot, obviously, filmed separately, even on different days, to be assembled later, rather than as one continuous action:

First a shot of slaves scurrying to clear the wreckage and horses of two chariots before the racers come round again.

Messala, knowing what’s just around the bend, crowds Ben-Hur’s chariot (with Heston at the reins) hard against the spina as they come around the turn.

As Messala and Ben-Hur gallop into the straightaway…

…the Roman continues to hem Ben-Hur against the spina, so close that guards on the spina have to leap onto the narrow curb to avoid being trampled (one doesn’t make it)…

…and the wreckage looms directly and unavoidably in Ben-Hur’s path as the slaves dash away to safety.

I draw on two sources to describe what happened when the next shot was filmed. One is Charlton Heston’s autobiography

In the Arena; the other is an account I read years ago but can’t remember where, and I can quote it now only from memory. Heston says that Yakima Canutt attached a safety chain between his son and the chariot before the shot, but Joe disconnected it after Yak walked away. Heston never learned why; he speculates that maybe Joe didn’t want to be shackled to the wreckage if anything went wrong. I think it’s also possible that Joe had rehearsed his team thoroughly enough that he simply didn’t think the chain was needed. In addition, Yak cautioned Joe to keep the chariot under 35 miles per hour to avoid being bounced out when he went over the ramp.

Marton called “Action!” and the two chariots came round the bend, Joe pacing himself to Messala’s chariot galloping beside him. Yak and Marton reflexively yelled “You’re going too fast!” — but of course it was pointless; Joe couldn’t have heard them over all the noise at that distance.

Joe’s chariot hit the ramp. In this frame you can see that the horses are just leaping clear on the other side. (You can also clearly see, with the frame frozen, that it’s not Charlton Heston driving.)

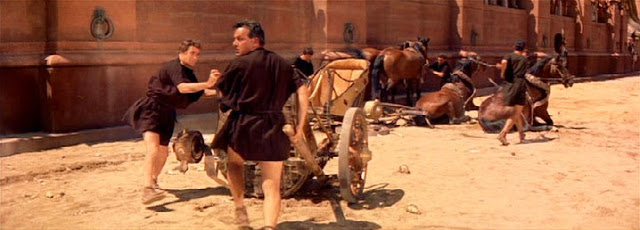

An instant later the team is safely clear and galloping away, but Joe’s trouble is just beginning.

The chariot begins to descend and Joe goes into free fall, hanging for dear life onto the front rail.

The heavy chariot is still coming down and Joe is almost perfectly perpendicular.

Now his feet are over, putting him in a back-bend. He’s a heartbeat away from either being crushed by the half-ton chariot or having the meat ripped from his bones by the bolts studding the underside. (And hey, look over to the right; see that? Yep, it’s one of Andrew Marton’s cameras. I’ll bet even the editors never saw it. The camera is on screen for eight frames, one-third of a second — just long enough to notice if you look that way. But of course nobody ever has.)

It was in this nanosecond that Joe Canutt displayed the combination of quick thinking and athletic prowess that marks the difference between a great stuntman and a dead one. It beggars belief, but here’s what he did: just before his body toppled completely over, he let go his grip on the front rail of the chariot, dropped to a handstand on the tongue just behind the horses’ flying hooves, and pushed himself to the side and clear away. Now I’ve never done a handspring off the tongue of a chariot at a full gallop, but I’m guessing it’s not the kind of thing you can practice for; either you can do it when you have to or you can’t. Joe Canutt could do it.

He didn’t escape entirely uscathed, though. Something on the passing chariot clipped him on the chin, requiring four stitches. He was back at work after half an hour.

Joe Canutt, against all odds, was alive and well, but the shot itself was a dead loss, and after seeing his son go halfway to glory and back again, Yakima Canutt was in no mood to try it again. But according to Heston, at the screening of the dailies the normally detached William Wyler nearly choked when he saw the shot. “Jee-zuss!“ he cried. “We have to use that!”

Yakima Canutt balked. “Don’t see how y’ gonna do that. I promised Chuck he’d win this race. I don’t believe he can catch that team on foot.”

But Wyler knew just how to salvage the shot. Neither Yak nor Heston was crazy about the idea but they did it:

With the chariot running at full speed, Heston faked the end of Joe Canutt’s tumble by clinging to the front of the chariot…

…then, “in about three blinks of an eye”, he clambered back in place and seized the reins once again. “It’s a scary shot,” Heston wrote, “– it scared me, anyway.” No doubt those three eye-blinks taught Charlton Heston a new respect for Joe Canutt, if any new respect were needed.

(UPDATE: Wyler biographer

Jan Herman gives a different account of how this solution was arrived at, but I’m going with Heston, who was there.)

Now let’s go back to the Alhambra Theatre in September 1960. Judah Ben-Hur’s flying header out of that chariot got a reaction from those 2,500 patrons unlike anything I’ve ever heard in a movie theater — or anywhere else, for that matter. Men bellowed. Women screamed. Not a soul in the house — and I include myself — could believe we saw what we were seeing. And again, remember that 80-foot screen. This wasn’t an image captured in a few thousand pixels on an HDTV. It was MGM Camera65, projected on a screen that looked like it covered two acres. When Joe Canutt’s body went sailing into the air, you had to move your head to follow it.

And when Charlton Heston climbed back into that chariot and gathered up the reins to race on, the joyful roar from that audience all but drowned out the Alhambra’s seven-channel sound system. It was like…oh, I don’t know. Imagine Babe Ruth hitting a grand-slam homer in Yankee Stadium with two men out in the bottom of the ninth in the seventh game of the World Series and the Yankees down by three runs. The way those Yankee fans would have responded — that’s what that audience did for the rest of the chariot race after that stunt. They cheered, they stomped, they whistled, they bounced in their seats shouting “Go! Go! Go!” Myself, I sat there wide-eyed, taking in the whole experience — what was happening on screen, and what was happening around me. It didn’t change my feelings about the rest of the picture, but it’s something I’ll never forget.

By finding a way to salvage Joe Canutt’s stunt-gone-wrong, William Wyler gave Ben-Hur something nobody knew it was missing — probably not even Wyler himself. He gave it a moment — a split-second, a heartbeat-and-a-half — when it actually looked like Judah Ben-Hur might not win the race after all. In art both high and low, there are certain givens that everybody knows going in. Oedipus will blind himself, Scrooge will reform, Anna Karenina will throw herself under the train, Luke will destroy the Death Star. And Ben-Hur will win the chariot race. When Joe Canutt was thrown out of his chariot, and when William Wyler figured out a way to keep the shot in the picture after all, the audience’s expectations were instantly upended, as surely as Joe Canutt had been.

Tristan Bernard once said, “Audiences want to be surprised, but by something they expect.” Joe Canutt (by accident) and William Wyler (by design) created a moment that achieved the near-impossible: it made Judah Ben-Hur winning the chariot race — which everybody expected — a genuine surprise.

For all the New York Times’s puffing about engrossing human drama, or Time Magazine’s mooning over lines of quiet poetry, I say Ben-Hur (1959) really pretty much boils down to the chariot race — and the chariot race boils down to that somersault Joe Canutt took on a miscalculated stunt. Don’t get me wrong, the whole race is brilliantly staged, shot and edited, but that moment makes it an emotional as well as a visceral experience. At that point, the chariot race still has nearly three minutes to run, and the picture itself nearly 50. But that’s the emotional climax of the race, and of the whole movie.

I admit, this hypothesis is something I concocted about a movie I didn’t like very much, to try to understand why so many people did. As I said, it’s no doubt an over-simplification. And yet, and yet — I can never prove it, but I’ll always suspect that some of those 11 Oscars, maybe even best picture itself, would have gone home with somebody else if Joe Canutt had been a little more cautious as he pointed his team toward that ramp.

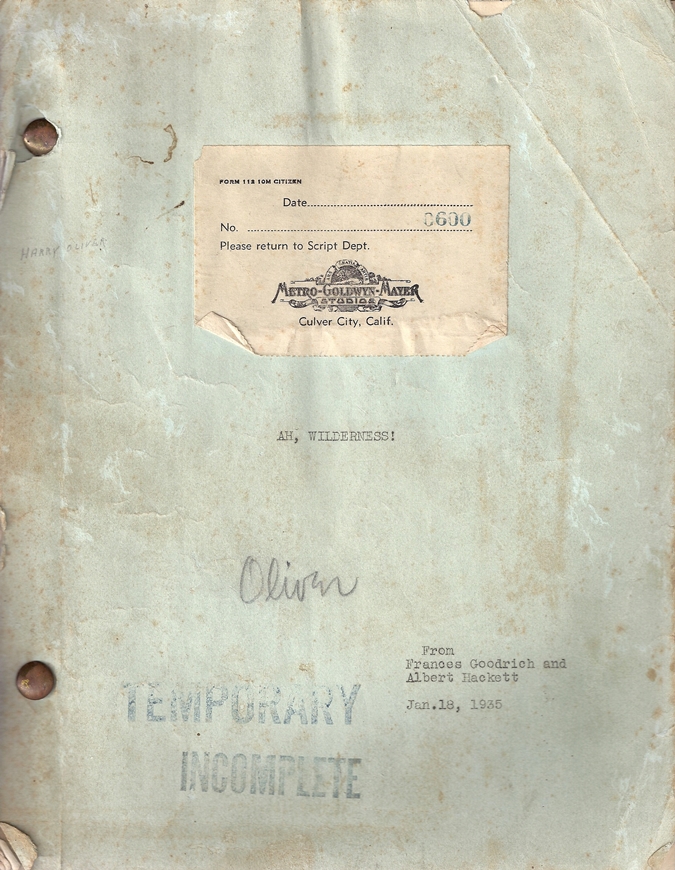

An interesting artifact has come into my hands on loan from an old friend. It’s an early draft of the screenplay for MGM’s 1935 movie of Eugene O’Neill’s Ah, Wilderness! by the husband-and-wife team of Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett.

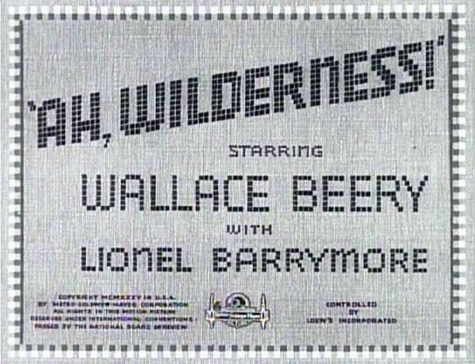

An interesting artifact has come into my hands on loan from an old friend. It’s an early draft of the screenplay for MGM’s 1935 movie of Eugene O’Neill’s Ah, Wilderness! by the husband-and-wife team of Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett. The first major difference is in the treatment of Wallace Beery’s role. Beery (left) gets top billing in the picture, playing Sid Davis, the brother of Spring Byington’s Essie Miller and the brother-in-law of Essie’s husband Nat (second-billed Lionel Barrymore, right). O’Neill’s play all takes place on one day — July 4, 1906 — but the Hacketts had expanded the time frame to open a week or two earlier (“late June”), before Sid enters the action (he comes back to the Miller household after being fired for drunkenness from his newspaper job in a neighboring town). So in this January 18 draft, Sid doesn’t show up until page 40 (of 93), on the morning of the Fourth. This would hardly do for a star of Beery’s standing at the time (I wouldn’t put it past him to have griped about it himself, loud and long), so a scene was added showing him going off with high hopes — for both his new job and his newfound sobriety — at the end of June, before slinking back to the Millers in time for the holiday. (“Ma! Pa! Uncle Sid’s come to spend the Fourth!” To which Sid mutters under his breath: “The Fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth, ad infinitum.”)

The first major difference is in the treatment of Wallace Beery’s role. Beery (left) gets top billing in the picture, playing Sid Davis, the brother of Spring Byington’s Essie Miller and the brother-in-law of Essie’s husband Nat (second-billed Lionel Barrymore, right). O’Neill’s play all takes place on one day — July 4, 1906 — but the Hacketts had expanded the time frame to open a week or two earlier (“late June”), before Sid enters the action (he comes back to the Miller household after being fired for drunkenness from his newspaper job in a neighboring town). So in this January 18 draft, Sid doesn’t show up until page 40 (of 93), on the morning of the Fourth. This would hardly do for a star of Beery’s standing at the time (I wouldn’t put it past him to have griped about it himself, loud and long), so a scene was added showing him going off with high hopes — for both his new job and his newfound sobriety — at the end of June, before slinking back to the Millers in time for the holiday. (“Ma! Pa! Uncle Sid’s come to spend the Fourth!” To which Sid mutters under his breath: “The Fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth, ad infinitum.”)

As for the second major difference, it’s another scene that doesn’t appear in O’Neill’s play — a major one, just over 15 minutes long. I don’t know when it was inserted into the script, but God bless the Hacketts for writing it, and Clarence Brown for directing it so beautifully, because it’s one of the best and funniest scenes in the whole movie. Most of it takes place during the graduation ceremony at the high school in this small Connecticut city, where Nat and Essie Miller’s middle son Richard (Eric Linden) will be the valedictorian. Before Richard’s speech, however, we’re treated to a generous sampling of the commencement program: the school glee club singing “The Blue Danube”, an earnest young student reciting Mark Antony’s funeral oration from Julius Caesar; a more nervous youngster offering Poe’s “The Bells” (“…of the bells bells bells bells bells bells bells…”) and studiously counting every “bells” off on his fingers; a girl student’s how-I-spent-my-summer-vacation travelogue about her family’s visit to the Swiss Alps; and my favorite, this young lady (I wish I knew her name) struggling doggedly through a clarinet solo, darting irritated glances toward her piano accompanist at every real and imagined mistake.

As for the second major difference, it’s another scene that doesn’t appear in O’Neill’s play — a major one, just over 15 minutes long. I don’t know when it was inserted into the script, but God bless the Hacketts for writing it, and Clarence Brown for directing it so beautifully, because it’s one of the best and funniest scenes in the whole movie. Most of it takes place during the graduation ceremony at the high school in this small Connecticut city, where Nat and Essie Miller’s middle son Richard (Eric Linden) will be the valedictorian. Before Richard’s speech, however, we’re treated to a generous sampling of the commencement program: the school glee club singing “The Blue Danube”, an earnest young student reciting Mark Antony’s funeral oration from Julius Caesar; a more nervous youngster offering Poe’s “The Bells” (“…of the bells bells bells bells bells bells bells…”) and studiously counting every “bells” off on his fingers; a girl student’s how-I-spent-my-summer-vacation travelogue about her family’s visit to the Swiss Alps; and my favorite, this young lady (I wish I knew her name) struggling doggedly through a clarinet solo, darting irritated glances toward her piano accompanist at every real and imagined mistake. In their adaptation, the Hacketts emphasized the one slim thread of plot in O’Neill’s nostalgic reverie of a youth he never had: the emotional growing pains of the Millers’ middle son Richard, from his jejune flirtation with radical politics to his blossoming romance with neighbor girl Muriel McComber (Cecilia Parker) and the mean-spirited oppostion of her father. In so doing, the Hacketts handed 25-year-old Eric Linden the opportunity to give the performance of his career — and he delivered in style. Never mind that he gets no better than fourth billing; Ah, Wilderness! is Eric Linden’s picture from beginning to end. And never mind that he was a good decade too old for the role; his boyishness made him look not a day over 16, and his performance did the rest. Linden had a busy career in the 1930s — mostly in B-pictures for RKO, Warners and MGM — without ever really becoming a star; this was his only chance to carry an A-picture on his own. After this it was back to Bs at Metro and on loan to various studios and independent producers. But before he finally closed out his career in 1943 with Criminals Within (for lowly Producers Releasing Corporation, the skid row flophouse of Hollywood studios), he would give one more performance that I’m sure everyone who ever saw it will remember to their dying day:

In their adaptation, the Hacketts emphasized the one slim thread of plot in O’Neill’s nostalgic reverie of a youth he never had: the emotional growing pains of the Millers’ middle son Richard, from his jejune flirtation with radical politics to his blossoming romance with neighbor girl Muriel McComber (Cecilia Parker) and the mean-spirited oppostion of her father. In so doing, the Hacketts handed 25-year-old Eric Linden the opportunity to give the performance of his career — and he delivered in style. Never mind that he gets no better than fourth billing; Ah, Wilderness! is Eric Linden’s picture from beginning to end. And never mind that he was a good decade too old for the role; his boyishness made him look not a day over 16, and his performance did the rest. Linden had a busy career in the 1930s — mostly in B-pictures for RKO, Warners and MGM — without ever really becoming a star; this was his only chance to carry an A-picture on his own. After this it was back to Bs at Metro and on loan to various studios and independent producers. But before he finally closed out his career in 1943 with Criminals Within (for lowly Producers Releasing Corporation, the skid row flophouse of Hollywood studios), he would give one more performance that I’m sure everyone who ever saw it will remember to their dying day: He was the Confederate soldier in Gone With the Wind who has just learned from Harry Davenport’s Dr. Meade that his leg will have to be amputated. He is on screen for less than three seconds, but his desperate cries (“Don’t cut! Don’t! — cut! Ple-e-e-e-ease!!”) have curdled the blood of millions of moviegoers for over 70 years. Oh yes, I’ll just bet you remember Eric Linden, all right.

He was the Confederate soldier in Gone With the Wind who has just learned from Harry Davenport’s Dr. Meade that his leg will have to be amputated. He is on screen for less than three seconds, but his desperate cries (“Don’t cut! Don’t! — cut! Ple-e-e-e-ease!!”) have curdled the blood of millions of moviegoers for over 70 years. Oh yes, I’ll just bet you remember Eric Linden, all right. The Hacketts deftly tinkered with the letter of O’Neill’s play, but Ah, Wilderness! the movie remained stoutly faithful to its spirit, and for that, a good share of the credit should go to director Clarence Brown. Brown’s career and work deserve more attention than they’ve gotten, and maybe someday I’ll have more to say about him. For now, I’ll simply observe that in his 53 pictures between 1920 and 1952 he directed a striking number of performers to their best-ever performances: Eric Linden here, Elizabeth Taylor in National Velvet, Claude Jarman Jr. in The Yearling, Juano Hernandez in Intruder in the Dust, George Brent in The Rains Came, Marie Dressler in Emma, and so on. An equally striking number gave their near-best for him: Garbo and Basil Rathbone in Anna Karenina, Mickey Rooney and Frank Morgan in The Human Comedy, Charles Boyer in Conquest, Paul Douglas in Angels in the Outfield — well, you get the idea. I could do a whole post just on Brown’s contribution to Ah, Wilderness!, but my topic here is what the picture’s success led to for MGM and Hollywood — consequences beyond what anyone could have expected. Clarence Brown had a lot to do with that success; let’s just leave it at that.

The Hacketts deftly tinkered with the letter of O’Neill’s play, but Ah, Wilderness! the movie remained stoutly faithful to its spirit, and for that, a good share of the credit should go to director Clarence Brown. Brown’s career and work deserve more attention than they’ve gotten, and maybe someday I’ll have more to say about him. For now, I’ll simply observe that in his 53 pictures between 1920 and 1952 he directed a striking number of performers to their best-ever performances: Eric Linden here, Elizabeth Taylor in National Velvet, Claude Jarman Jr. in The Yearling, Juano Hernandez in Intruder in the Dust, George Brent in The Rains Came, Marie Dressler in Emma, and so on. An equally striking number gave their near-best for him: Garbo and Basil Rathbone in Anna Karenina, Mickey Rooney and Frank Morgan in The Human Comedy, Charles Boyer in Conquest, Paul Douglas in Angels in the Outfield — well, you get the idea. I could do a whole post just on Brown’s contribution to Ah, Wilderness!, but my topic here is what the picture’s success led to for MGM and Hollywood — consequences beyond what anyone could have expected. Clarence Brown had a lot to do with that success; let’s just leave it at that. When the picture went into production in the fall of 1936, Aurania Rouverol’s Skidding had a new title, A Family Affair, and George B. Seitz was directing from a script by Kay Van Riper. It reunited a hefty chunk of the cast from Ah, Wilderness!: Lionel Barrymore, Spring Byington, Mickey Rooney, Charles Grapewin. Also back were Eric Linden and Cecilia Parker, romantically paired once again — only this time she was the one in the family and he was the neighboring sweetheart. The picture was shot on the same backlot “New England Street” that had been built for Ah, Wilderness!, and the new family “lived” in the same house. If you have any lingering doubt that this new picture was designed to evoke pleasant memories of the earlier one, here’s the title frame from Ah, Wilderness!…

When the picture went into production in the fall of 1936, Aurania Rouverol’s Skidding had a new title, A Family Affair, and George B. Seitz was directing from a script by Kay Van Riper. It reunited a hefty chunk of the cast from Ah, Wilderness!: Lionel Barrymore, Spring Byington, Mickey Rooney, Charles Grapewin. Also back were Eric Linden and Cecilia Parker, romantically paired once again — only this time she was the one in the family and he was the neighboring sweetheart. The picture was shot on the same backlot “New England Street” that had been built for Ah, Wilderness!, and the new family “lived” in the same house. If you have any lingering doubt that this new picture was designed to evoke pleasant memories of the earlier one, here’s the title frame from Ah, Wilderness!… …and here’s the same frame from A Family Affair. The new picture took place in the “present day” (i.e., 1936) instead of a rose-colored turn of the century, but otherwise it followed the benevolent formula laid down by Eugene O’Neill in his change-of-pace comedy: the friendly, cozy big-small-town where everybody knows everybody else, the close-knit family bound by ties of affection and respect, the periodic heart-to-heart talks between father and son. The family of newspaper publisher Nat Miller in Ah, Wilderness! were the clear progenitors of Judge James K. Hardy and his clan — at least, by the time MGM had brought the Hardys to the screen. (In fact, ironically, Aurania Rouverol’s play had beaten O’Neill’s to Broadway by nearly five-and-a-half years; Skidding had a longer run, too.)

…and here’s the same frame from A Family Affair. The new picture took place in the “present day” (i.e., 1936) instead of a rose-colored turn of the century, but otherwise it followed the benevolent formula laid down by Eugene O’Neill in his change-of-pace comedy: the friendly, cozy big-small-town where everybody knows everybody else, the close-knit family bound by ties of affection and respect, the periodic heart-to-heart talks between father and son. The family of newspaper publisher Nat Miller in Ah, Wilderness! were the clear progenitors of Judge James K. Hardy and his clan — at least, by the time MGM had brought the Hardys to the screen. (In fact, ironically, Aurania Rouverol’s play had beaten O’Neill’s to Broadway by nearly five-and-a-half years; Skidding had a longer run, too.) In 1946, the year of the last regular Andy Hardy picture (Love Laughs at Andy Hardy), there was a sort of closing of the circle on Ah, Wilderness! Producer Arthur Freed, still flush from his rousing success with Meet Me in St. Louis (which itself was a very close cousin to Ah, Wilderness!) conceived the idea of turning O’Neill’s play into a musical. So the Hardys moved out of their comfy white house and the Millers moved back in (and painted it yellow for Technicolor), and the result was Summer Holiday. This time Andy Hardy himself, Mickey Rooney (who had played Tommy, the youngest Miller boy, in Ah, Wilderness!), was promoted into the role of Richard Miller, and Richard and his Muriel (Gloria DeHaven) got the top billing (thanks to the Hacketts’ tweakings of O’Neill, here preserved and enhanced) that Eric Linden and Cecilia Parker had deserved but been denied in 1935.

In 1946, the year of the last regular Andy Hardy picture (Love Laughs at Andy Hardy), there was a sort of closing of the circle on Ah, Wilderness! Producer Arthur Freed, still flush from his rousing success with Meet Me in St. Louis (which itself was a very close cousin to Ah, Wilderness!) conceived the idea of turning O’Neill’s play into a musical. So the Hardys moved out of their comfy white house and the Millers moved back in (and painted it yellow for Technicolor), and the result was Summer Holiday. This time Andy Hardy himself, Mickey Rooney (who had played Tommy, the youngest Miller boy, in Ah, Wilderness!), was promoted into the role of Richard Miller, and Richard and his Muriel (Gloria DeHaven) got the top billing (thanks to the Hacketts’ tweakings of O’Neill, here preserved and enhanced) that Eric Linden and Cecilia Parker had deserved but been denied in 1935. Even by 1948, the “reinventions” — of America and of Ah, Wilderness! — that Mickey Rooney talked about had begun to outstrip Andy Hardy, but Andy cast a long shadow for decades after the series itself ebbed. Sometimes the influence was direct and deliberate, as with the Archie comics that started in 1941 in blatant imitation of Andy Hardy and are still around today. Sometimes it was indirect but distinct, as in TV sitcoms from Father Knows Best and Leave It to Beaver, through The Partridge Family and The Brady Bunch, to Eight Is Enough and Modern Family. In them all, we can still discern the basic template with which L.B. Mayer “confected” small-town American life, in MGM’s conscious imitation of the way Eugene O’Neill had “confected” an imaginary youth for himself in New London, Conn. The shadow of Andy Hardy is really the shadow of Ah, Wilderness! (And let’s not forget Meet Me in St. Louis and the Technicolor musicals inspired by it, like Centennial Summer, State Fair, On Moonlight Bay, By the Light of the Silvery Moon, and yes, Summer Holiday, all with a clear kinship to O’Neill’s comedy.)

Even by 1948, the “reinventions” — of America and of Ah, Wilderness! — that Mickey Rooney talked about had begun to outstrip Andy Hardy, but Andy cast a long shadow for decades after the series itself ebbed. Sometimes the influence was direct and deliberate, as with the Archie comics that started in 1941 in blatant imitation of Andy Hardy and are still around today. Sometimes it was indirect but distinct, as in TV sitcoms from Father Knows Best and Leave It to Beaver, through The Partridge Family and The Brady Bunch, to Eight Is Enough and Modern Family. In them all, we can still discern the basic template with which L.B. Mayer “confected” small-town American life, in MGM’s conscious imitation of the way Eugene O’Neill had “confected” an imaginary youth for himself in New London, Conn. The shadow of Andy Hardy is really the shadow of Ah, Wilderness! (And let’s not forget Meet Me in St. Louis and the Technicolor musicals inspired by it, like Centennial Summer, State Fair, On Moonlight Bay, By the Light of the Silvery Moon, and yes, Summer Holiday, all with a clear kinship to O’Neill’s comedy.) The 1960s were, in a literal if not a figurative sense, a golden age for movie musicals; they made more money (a total of over $250 million, real money back then — about $2.128 billion today) and won more awards (four best picture Oscars, best director for each one, 34 Oscars in the various craft categories, plus a more-than-respectable smattering of acting awards and nominations) than they ever had before or would again. There were West Side Story, Gypsy, The Music Man, Bye Bye Birdie, The Sound of Music, My Fair Lady, Mary Poppins, Thoroughly Modern Millie, How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, Half a Sixpence, Funny Girl, Oliver!…

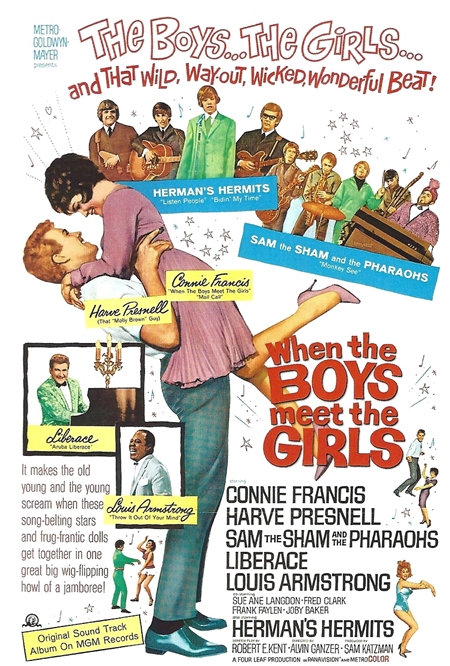

The 1960s were, in a literal if not a figurative sense, a golden age for movie musicals; they made more money (a total of over $250 million, real money back then — about $2.128 billion today) and won more awards (four best picture Oscars, best director for each one, 34 Oscars in the various craft categories, plus a more-than-respectable smattering of acting awards and nominations) than they ever had before or would again. There were West Side Story, Gypsy, The Music Man, Bye Bye Birdie, The Sound of Music, My Fair Lady, Mary Poppins, Thoroughly Modern Millie, How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, Half a Sixpence, Funny Girl, Oliver!… It was in this atmosphere, right smack in the middle of the decade, that Girl Crazy emerged in its third and final screen incarnation. It was planned as a vehicle for pop chanteuse Connie Francis. Her popularity was just beginning to wane under the onslaught of the Beatles-led British Invasion, but we can see that only in retrospect; at the time she seemed as popular as ever. And she was very popular indeed — the first female to have two consecutive number one hits (“Everybody’s Somebody’s Fool” and “My Heart Has a Mind of Its Own” in 1960) and the youngest entertainer to headline in Las Vegas and at New York’s Copacabana (that same year). Also in 1960, Francis made her screen debut in MGM’s Where the Boys Are (and had another big hit with the title tune). It was the custom in those days, when a singer had a hit song, to make the follow-up single as much like the hit as possible, so MGM and Francis followed Where the Boys Are with Follow the Boys. And that’s why, when the studio decided to revamp Girl Crazy for Connie Francis, the show got a new title (and a new song for Connie to croon): When the Boys Meet the Girls.

It was in this atmosphere, right smack in the middle of the decade, that Girl Crazy emerged in its third and final screen incarnation. It was planned as a vehicle for pop chanteuse Connie Francis. Her popularity was just beginning to wane under the onslaught of the Beatles-led British Invasion, but we can see that only in retrospect; at the time she seemed as popular as ever. And she was very popular indeed — the first female to have two consecutive number one hits (“Everybody’s Somebody’s Fool” and “My Heart Has a Mind of Its Own” in 1960) and the youngest entertainer to headline in Las Vegas and at New York’s Copacabana (that same year). Also in 1960, Francis made her screen debut in MGM’s Where the Boys Are (and had another big hit with the title tune). It was the custom in those days, when a singer had a hit song, to make the follow-up single as much like the hit as possible, so MGM and Francis followed Where the Boys Are with Follow the Boys. And that’s why, when the studio decided to revamp Girl Crazy for Connie Francis, the show got a new title (and a new song for Connie to croon): When the Boys Meet the Girls. Connie’s co-star was Harve Presnell, a veteran of the opera and concert stage who had made a splash on Broadway in The Unsinkable Molly Brown, then won a Golden Globe for the movie version opposite Debbie Reynolds. At that stage of his career he was tall and handsome, with a lush baritone voice — a slightly younger, blonde version of Howard Keel. But his timing couldn’t have been worse: By 1965 not even Keel was getting enough work to keep him busy; he hadn’t made a musical since Kismet in 1955, and had segued into straight acting roles. Presnell would have a tougher time of that; as a screen actor he was a little stiff, without Keel’s comfort in front of a camera. He made one more major movie, stealing Paint Your Wagon from Clint Eastwood and Lee Marvin with his rendition of “They Call the Wind Maria”, then it was back to regional theater and Broadway tours until he returned to movies as a character actor in his 60s and 70s. Things worked better for him then; the stiffness that had looked a bit wooden in his youth seemed more like patrician dignity in his senior years, and he had a distinguished second career in movies (Fargo, Saving Private Ryan, Flags of Our Fathers, Evan Almighty) before dying of pancreatic cancer at 75 in 2009.

Connie’s co-star was Harve Presnell, a veteran of the opera and concert stage who had made a splash on Broadway in The Unsinkable Molly Brown, then won a Golden Globe for the movie version opposite Debbie Reynolds. At that stage of his career he was tall and handsome, with a lush baritone voice — a slightly younger, blonde version of Howard Keel. But his timing couldn’t have been worse: By 1965 not even Keel was getting enough work to keep him busy; he hadn’t made a musical since Kismet in 1955, and had segued into straight acting roles. Presnell would have a tougher time of that; as a screen actor he was a little stiff, without Keel’s comfort in front of a camera. He made one more major movie, stealing Paint Your Wagon from Clint Eastwood and Lee Marvin with his rendition of “They Call the Wind Maria”, then it was back to regional theater and Broadway tours until he returned to movies as a character actor in his 60s and 70s. Things worked better for him then; the stiffness that had looked a bit wooden in his youth seemed more like patrician dignity in his senior years, and he had a distinguished second career in movies (Fargo, Saving Private Ryan, Flags of Our Fathers, Evan Almighty) before dying of pancreatic cancer at 75 in 2009.

But one of Karger’s bright ideas really takes stupidity to undreamed-of heights, and that’s in his treatment of “Bidin’ My Time”. The number is given to Herman’s Hermits, sitting on and around a flatbed truck while the rest of the young cast gets busy building Ginger’s dude ranch. At first things seem to go well with the song: it’s an almost witty idea, handing this lazy cowboy lullaby to these slightly nerdy lads from Manchester. Peter Noone’s wispy tenor voice slides nicely into the verse, then the refrain moves into a ricky-ticky soft-samba rhythm similar to the Beatles’ version of “Till There Was You”. Then, trouble. Now as just about everybody but Fred Karger and Peter Noone knew by 1965, the song is supposed to go like this:

But one of Karger’s bright ideas really takes stupidity to undreamed-of heights, and that’s in his treatment of “Bidin’ My Time”. The number is given to Herman’s Hermits, sitting on and around a flatbed truck while the rest of the young cast gets busy building Ginger’s dude ranch. At first things seem to go well with the song: it’s an almost witty idea, handing this lazy cowboy lullaby to these slightly nerdy lads from Manchester. Peter Noone’s wispy tenor voice slides nicely into the verse, then the refrain moves into a ricky-ticky soft-samba rhythm similar to the Beatles’ version of “Till There Was You”. Then, trouble. Now as just about everybody but Fred Karger and Peter Noone knew by 1965, the song is supposed to go like this:

By the time Girl Crazy came to the screen again, Hollywood’s attitude toward musicals had changed diametrically, and with a will. A look at Clive Hirschhorn’s comprehensive coffee-table book

By the time Girl Crazy came to the screen again, Hollywood’s attitude toward musicals had changed diametrically, and with a will. A look at Clive Hirschhorn’s comprehensive coffee-table book  So let’s recap: After less than two weeks, Girl Crazy was four days behind schedule and 60 grand over budget. Judy Garland was frazzled, Roger Edens was furious. Obviously, Berkeley had to go. Freed removed him from the picture and replaced him with Norman Taurog.

So let’s recap: After less than two weeks, Girl Crazy was four days behind schedule and 60 grand over budget. Judy Garland was frazzled, Roger Edens was furious. Obviously, Berkeley had to go. Freed removed him from the picture and replaced him with Norman Taurog.

At the risk of becoming monotonous, let us count the ways. First, of course, is that rambunctious version of “Treat Me Rough”, which June Allyson invests with an innocent tomboy eroticism (she’s like a less obnoxious Betty Hutton) that must have had the Hays Office wondering if this sort of thing was really okay, then shrugging and deciding it was all just good clean fun after all.

At the risk of becoming monotonous, let us count the ways. First, of course, is that rambunctious version of “Treat Me Rough”, which June Allyson invests with an innocent tomboy eroticism (she’s like a less obnoxious Betty Hutton) that must have had the Hays Office wondering if this sort of thing was really okay, then shrugging and deciding it was all just good clean fun after all. The quirky love-hate duet “Could You Use Me?” was something that Eddie Quillan and Arline Judge actually might have handled pretty well if RKO had deigned to include it in 1932. But they didn’t, and it was left to Mickey and Judy to bring it to the screen. Filmed in punishing 112-degree heat on location on a desert road outside Palm Springs (with pickup shots in the relative comfort of a soundstage back in Culver City), it’s a cheerful charmer in which Judy manages to suggest that Ginger’s resistance to Danny’s brash advances is already beginning to melt.

The quirky love-hate duet “Could You Use Me?” was something that Eddie Quillan and Arline Judge actually might have handled pretty well if RKO had deigned to include it in 1932. But they didn’t, and it was left to Mickey and Judy to bring it to the screen. Filmed in punishing 112-degree heat on location on a desert road outside Palm Springs (with pickup shots in the relative comfort of a soundstage back in Culver City), it’s a cheerful charmer in which Judy manages to suggest that Ginger’s resistance to Danny’s brash advances is already beginning to melt. “Embraceable You” is presented at a party for Ginger, in a scene that includes the movie’s only non-Gershwin interpolation: a chorus of “Happy Birthday to You” from Cody College’s assembled student body. Judy sings to the boys, then dances with them all, one by one and in groups, with an extended pas de deux with dance director Charles Walters. Later, after graduating to full direction himself, Walters helmed Judy in Easter Parade (’48), Summer Stock (’50), and her triumphant one-woman show at Broadway’s Palace Theatre in 1951.

“Embraceable You” is presented at a party for Ginger, in a scene that includes the movie’s only non-Gershwin interpolation: a chorus of “Happy Birthday to You” from Cody College’s assembled student body. Judy sings to the boys, then dances with them all, one by one and in groups, with an extended pas de deux with dance director Charles Walters. Later, after graduating to full direction himself, Walters helmed Judy in Easter Parade (’48), Summer Stock (’50), and her triumphant one-woman show at Broadway’s Palace Theatre in 1951. When Danny Churchill attends a party at the Governor’s Mansion to lobby against the closing of Cody, he meets up with his old pal Tommy Dorsey, and that sets the stage for a nifty piece of Big Band Era history: Tommy Dorsey and his Orchestra in a marvelous pop-concert rendition of “Fascinating Rhythm”. It’s a jumpin’ arrangement, and features a solo by “Danny Churchill” on piano. In fact, Mickey Rooney’s playing was dubbed by Arthur Schutt; still, as his keyboard fingering in the scene makes clear, Rooney was an accomplished pianist himself, and to the end of his days he spoke of the thrill of getting to perform “Fascinating Rhythm” with Dorsey and his band. (No doubt, even though the number had been prerecorded on MGM’s music stage, the band — including guest soloist Rooney — played for real on the set.)

When Danny Churchill attends a party at the Governor’s Mansion to lobby against the closing of Cody, he meets up with his old pal Tommy Dorsey, and that sets the stage for a nifty piece of Big Band Era history: Tommy Dorsey and his Orchestra in a marvelous pop-concert rendition of “Fascinating Rhythm”. It’s a jumpin’ arrangement, and features a solo by “Danny Churchill” on piano. In fact, Mickey Rooney’s playing was dubbed by Arthur Schutt; still, as his keyboard fingering in the scene makes clear, Rooney was an accomplished pianist himself, and to the end of his days he spoke of the thrill of getting to perform “Fascinating Rhythm” with Dorsey and his band. (No doubt, even though the number had been prerecorded on MGM’s music stage, the band — including guest soloist Rooney — played for real on the set.) That party leads to the inevitable misunderstanding when Ginger believes Danny has returned to his girl-crazy ways with the governor’s daughter (Frances Rafferty). It all gets sorted out in time for a happy ending, natch, but not before Judy Garland gets the opportunity — Hallelujah! — to redeem the tawdry vandalism of “But Not for Me” back in 1932. This is not only the high point of Girl Crazy — it’s the high point of Judy Garland’s entire career. With all due respect to “Over the Rainbow”, “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas”, “The Man That Got Away” or anything else you care to name, this is Judy’s best. Co-star Gil Stratton talked about watching the number being shot and said “it was something you ought to have paid admission to see.” The simplicity of Taurog’s staging, the delicate cinematography of William Daniels, and the combined artistry of Judy and and the Gershwin brothers all fuse into the kind of magic that the Hollywood of 1943 had led audiences to take for granted. Judy Garland was as good as it got, then or ever after, and here’s the proof.

That party leads to the inevitable misunderstanding when Ginger believes Danny has returned to his girl-crazy ways with the governor’s daughter (Frances Rafferty). It all gets sorted out in time for a happy ending, natch, but not before Judy Garland gets the opportunity — Hallelujah! — to redeem the tawdry vandalism of “But Not for Me” back in 1932. This is not only the high point of Girl Crazy — it’s the high point of Judy Garland’s entire career. With all due respect to “Over the Rainbow”, “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas”, “The Man That Got Away” or anything else you care to name, this is Judy’s best. Co-star Gil Stratton talked about watching the number being shot and said “it was something you ought to have paid admission to see.” The simplicity of Taurog’s staging, the delicate cinematography of William Daniels, and the combined artistry of Judy and and the Gershwin brothers all fuse into the kind of magic that the Hollywood of 1943 had led audiences to take for granted. Judy Garland was as good as it got, then or ever after, and here’s the proof. Originally, Girl Crazy was to end with a reprise of “Embraceable You”, Mickey and Judy surrounded by the rest of the cast as the orchestra swells up and out. But Busby Berkeley’s flamboyant staging of “I Got Rhythm”, scheduled to come almost 20 minutes before the end, threatened to turn anything that followed into a dribbling anticlimax. There was some hurried reshuffling of the script and music, and Girl Crazy as it was released on November 26 ended with “I Got Rhythm”. It must have positively galled Roger Edens; he’d gotten his way and had Berkeley canned from the picture, and now here was Berkeley literally getting the last word — cracking whips, blazing six-guns and all. But it was the right call, and, however grudgingly, Edens probably had to admit it.

Originally, Girl Crazy was to end with a reprise of “Embraceable You”, Mickey and Judy surrounded by the rest of the cast as the orchestra swells up and out. But Busby Berkeley’s flamboyant staging of “I Got Rhythm”, scheduled to come almost 20 minutes before the end, threatened to turn anything that followed into a dribbling anticlimax. There was some hurried reshuffling of the script and music, and Girl Crazy as it was released on November 26 ended with “I Got Rhythm”. It must have positively galled Roger Edens; he’d gotten his way and had Berkeley canned from the picture, and now here was Berkeley literally getting the last word — cracking whips, blazing six-guns and all. But it was the right call, and, however grudgingly, Edens probably had to admit it.

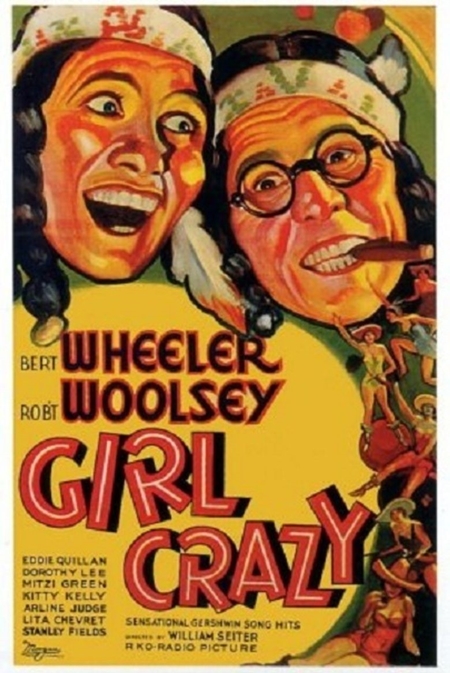

I have this fantasy in which I imagine that a scout from RKO Radio Pictures early in 1931 is told to go see Girl Crazy on Broadway and to report back about its potential as a movie. In his report, does he say, “The score is amazing; George and Ira Gershwin have written some songs that will be sung as long as singers sing”? Or “This Ethel Merman is dynamite; she electrifies an audience and she can put a song over like an artillery barrage”? Or “Ginger Rogers is a real charmer who has already shown that she photographs well; with care she could be groomed into a major star”? Does he say any of this? He does not. Instead, this brilliant showbiz oracle tells the front office, “This might make a good vehicle for Wheeler and Woolsey.”

I have this fantasy in which I imagine that a scout from RKO Radio Pictures early in 1931 is told to go see Girl Crazy on Broadway and to report back about its potential as a movie. In his report, does he say, “The score is amazing; George and Ira Gershwin have written some songs that will be sung as long as singers sing”? Or “This Ethel Merman is dynamite; she electrifies an audience and she can put a song over like an artillery barrage”? Or “Ginger Rogers is a real charmer who has already shown that she photographs well; with care she could be groomed into a major star”? Does he say any of this? He does not. Instead, this brilliant showbiz oracle tells the front office, “This might make a good vehicle for Wheeler and Woolsey.” Almost a third member of the (not really a) team was diminutive Dorothy Lee; she appeared in 16 of Wheeler and Woolsey’s pictures. A good physical match for Wheeler (he was five foot four, she five foot exactly), Lee served as a romantic partner for him, giving Wheeler (and the audience) a little relief from the obnoxious blowhard Woolsey. So it was in Girl Crazy, in which Wheeler took the role played on Broadway by Willie Howard (whose intransigence had killed the show before its time). The cabbie’s name was de-ethnicized from Gieber Goldfarb to Jimmy Deegan, the character was divested of the comic Yiddish persona that was Howard’s stock in trade, and Lee was brought in as Patsy, “the gal of the golden west”, to duet with Wheeler in one of only four musical numbers in the movie.

Almost a third member of the (not really a) team was diminutive Dorothy Lee; she appeared in 16 of Wheeler and Woolsey’s pictures. A good physical match for Wheeler (he was five foot four, she five foot exactly), Lee served as a romantic partner for him, giving Wheeler (and the audience) a little relief from the obnoxious blowhard Woolsey. So it was in Girl Crazy, in which Wheeler took the role played on Broadway by Willie Howard (whose intransigence had killed the show before its time). The cabbie’s name was de-ethnicized from Gieber Goldfarb to Jimmy Deegan, the character was divested of the comic Yiddish persona that was Howard’s stock in trade, and Lee was brought in as Patsy, “the gal of the golden west”, to duet with Wheeler in one of only four musical numbers in the movie.  Musicals, a novelty in the late ’20s, had worn out their welcome by 1932 and become a drug on the market; theater owners were known to reassure audiences in ads and posters that their current offering was “Not a Musical!” (The Big Revival over at Warner Bros. was still a year away.) In this atmosphere, no one at RKO was in a mood to look twice at the Gershwins’ songs in Girl Crazy. Instead, taking their cue from Willie Howard and William Kent having been the ones with star billing on Broadway, the studio jettisoned most of the score and refashioned the book — the weakest thing about the show — to suit their hot new team. So it is that in the movie, it isn’t Eddie Quillan’s Danny Churchill who takes a taxi from Manhattan to Arizona, it’s the gambler Slick (new surname: Foster) who hops into Jimmy Deegan’s cab for the trip out west. (The lady in the back seat with Woolsey is Kitty Kelly, playing what’s left of Ethel Merman’s role.) Two huge chunks of the picture’s modest 74-minute running time are eaten up by (1) Wheeler and Woolsey’s misadventures on the road to Arizona and (2) further misadventures later, when the action adjourns to Mexico.

Musicals, a novelty in the late ’20s, had worn out their welcome by 1932 and become a drug on the market; theater owners were known to reassure audiences in ads and posters that their current offering was “Not a Musical!” (The Big Revival over at Warner Bros. was still a year away.) In this atmosphere, no one at RKO was in a mood to look twice at the Gershwins’ songs in Girl Crazy. Instead, taking their cue from Willie Howard and William Kent having been the ones with star billing on Broadway, the studio jettisoned most of the score and refashioned the book — the weakest thing about the show — to suit their hot new team. So it is that in the movie, it isn’t Eddie Quillan’s Danny Churchill who takes a taxi from Manhattan to Arizona, it’s the gambler Slick (new surname: Foster) who hops into Jimmy Deegan’s cab for the trip out west. (The lady in the back seat with Woolsey is Kitty Kelly, playing what’s left of Ethel Merman’s role.) Two huge chunks of the picture’s modest 74-minute running time are eaten up by (1) Wheeler and Woolsey’s misadventures on the road to Arizona and (2) further misadventures later, when the action adjourns to Mexico.  As for those four songs, only three were from the show. The movie opens promisingly with an amusing, if abbreviated, rendition of “Bidin’ My Time”, with four singing cowboys moseyin’ along on the back of the same overburdened horse, while the camera moves through the Custerville cemetery from the grave of one luckless sheriff to the next, and the next.

As for those four songs, only three were from the show. The movie opens promisingly with an amusing, if abbreviated, rendition of “Bidin’ My Time”, with four singing cowboys moseyin’ along on the back of the same overburdened horse, while the camera moves through the Custerville cemetery from the grave of one luckless sheriff to the next, and the next. A few minutes later comes “You’ve Got What Gets Me” a new song by George and Ira written for the movie. (In point of fact, it wasn’t entirely new; it was a reworking of another song, “Your Eyes, Your Smile”, which had been cut from the Broadway production of Funny Face before it opened in 1927.) This is a light romantic duet between Wheeler and Dorothy Lee (already, as noted, a staple of their pictures together), followed by a sprightly tap dance in which they’re joined by little Mitzi Green as Wheeler’s pesky sister. Toward the end of her life, Dorothy Lee remembered Girl Crazy with bitter disgust as the movie where they photographed her behind a post (“I saw it once,” she said. “I couldn’t look at it again.”), and this frame from the dance shows she wasn’t being hypersensitive — you can just about make out her elbows (she’s dancing to the left of Wheeler). Why would anybody bother to stage a tap dance on a set dominated by an enormous vine-covered wishing well right in the middle of the floor (and seemingly taking up half of it)? It’s hard to comprehend — but then, the songs simply weren’t a priority.

A few minutes later comes “You’ve Got What Gets Me” a new song by George and Ira written for the movie. (In point of fact, it wasn’t entirely new; it was a reworking of another song, “Your Eyes, Your Smile”, which had been cut from the Broadway production of Funny Face before it opened in 1927.) This is a light romantic duet between Wheeler and Dorothy Lee (already, as noted, a staple of their pictures together), followed by a sprightly tap dance in which they’re joined by little Mitzi Green as Wheeler’s pesky sister. Toward the end of her life, Dorothy Lee remembered Girl Crazy with bitter disgust as the movie where they photographed her behind a post (“I saw it once,” she said. “I couldn’t look at it again.”), and this frame from the dance shows she wasn’t being hypersensitive — you can just about make out her elbows (she’s dancing to the left of Wheeler). Why would anybody bother to stage a tap dance on a set dominated by an enormous vine-covered wishing well right in the middle of the floor (and seemingly taking up half of it)? It’s hard to comprehend — but then, the songs simply weren’t a priority.  But, with all due sympathy to Ms. Lee, that’s not the worst. The absolute nadir of RKO’s Girl Crazy — lower than any of Wheeler and Woolsey’s comedy, already too low by half — comes with the disgraceful treatment accorded “But Not for Me”. What on Broadway had been a wistful solo of lost love by Ginger Rogers was revamped as a trio for Eddie Quillan as Danny, Arline Judge as Molly, and Mitzi Green trying to patch things up between them. Ira’s lyric was twisted around to say the exact opposite of what he wrote (“Beatrice Fairfax, don’t you dare/Ever tell me he won’t care…”), and George’s tempo was sped up until the song sounded like the merry-go-round gone wild in Strangers on a Train. Quillan and Judge were hardly singers (which may explain the breakneck tempo, always easier for non-singers to handle), and they rush through the song as if they have to be someplace; Quillan darts off-camera before the music even tinkles to a stop. The song comes off like a playground argument between two petulant kids. It’s followed by a reprise in which Green tries to cheer Judge up by using the song to do impressions (and pretty good ones, too) of Bing Crosby, Roscoe Ates, George Arliss and Edna May Oliver. This plays oddly today, especially with audiences who never heard of Ates, Arliss or Oliver, but at least it had a counterpart in the original show: Willie Howard was famous for his impressions, and the book incorporated them by having the cabbie try to cheer Ginger Rogers’ Molly with a reprise a la Rudy Vallee and Maurice Chevalier — but only after Ginger had already given the song its full soulful due. This movie never bothers to do that.

But, with all due sympathy to Ms. Lee, that’s not the worst. The absolute nadir of RKO’s Girl Crazy — lower than any of Wheeler and Woolsey’s comedy, already too low by half — comes with the disgraceful treatment accorded “But Not for Me”. What on Broadway had been a wistful solo of lost love by Ginger Rogers was revamped as a trio for Eddie Quillan as Danny, Arline Judge as Molly, and Mitzi Green trying to patch things up between them. Ira’s lyric was twisted around to say the exact opposite of what he wrote (“Beatrice Fairfax, don’t you dare/Ever tell me he won’t care…”), and George’s tempo was sped up until the song sounded like the merry-go-round gone wild in Strangers on a Train. Quillan and Judge were hardly singers (which may explain the breakneck tempo, always easier for non-singers to handle), and they rush through the song as if they have to be someplace; Quillan darts off-camera before the music even tinkles to a stop. The song comes off like a playground argument between two petulant kids. It’s followed by a reprise in which Green tries to cheer Judge up by using the song to do impressions (and pretty good ones, too) of Bing Crosby, Roscoe Ates, George Arliss and Edna May Oliver. This plays oddly today, especially with audiences who never heard of Ates, Arliss or Oliver, but at least it had a counterpart in the original show: Willie Howard was famous for his impressions, and the book incorporated them by having the cabbie try to cheer Ginger Rogers’ Molly with a reprise a la Rudy Vallee and Maurice Chevalier — but only after Ginger had already given the song its full soulful due. This movie never bothers to do that. The following year would come the game-changer: Warner Bros. (and Busby Berkeley) with the spectacular hat trick of 42nd Street, Gold Diggers of 1933 and Footlight Parade to put musicals back in vogue again, where they would remain for decades — even Poverty Row studios like Republic, Monogram and PRC would regularly try their hands at them. But all that came too late to help RKO’s Girl Crazy. It was born before its time; the studio didn’t appreciate the property it had, and didn’t have the wit, confidence or foresight to do what should have been done with it.

The following year would come the game-changer: Warner Bros. (and Busby Berkeley) with the spectacular hat trick of 42nd Street, Gold Diggers of 1933 and Footlight Parade to put musicals back in vogue again, where they would remain for decades — even Poverty Row studios like Republic, Monogram and PRC would regularly try their hands at them. But all that came too late to help RKO’s Girl Crazy. It was born before its time; the studio didn’t appreciate the property it had, and didn’t have the wit, confidence or foresight to do what should have been done with it. This post has grown in the planning, to the point where I’m putting it up in two parts (maybe more; we’ll see how things shake out). I have an epic tale to tell, nothing less than the rise and fall of the Hollywood musical, as reflected in the screen career of a single property: Girl Crazy, the 1930 Broadway hit with songs by George and Ira Gershwin, book by Guy Bolton and John McGowan.

This post has grown in the planning, to the point where I’m putting it up in two parts (maybe more; we’ll see how things shake out). I have an epic tale to tell, nothing less than the rise and fall of the Hollywood musical, as reflected in the screen career of a single property: Girl Crazy, the 1930 Broadway hit with songs by George and Ira Gershwin, book by Guy Bolton and John McGowan. Merman’s debut alone was enough to make Girl Crazy‘s opening a Broadway landmark, but there was more. Others present that night wouldn’t make it big until later, but the fact that they were there at all is enough to make you pray for time travel. For starters, there was the man who put together the pit orchestra: Ernest Loring “Red” Nichols, age 25, one of the busiest musicians in town. He was an accomplished cornetist who could play equally well “hot” and “straight”, and he had already made hundreds of Dixieland recordings for Brunswick Records, usually with an ad hoc band billed as Red Nichols and his Five Pennies.

Merman’s debut alone was enough to make Girl Crazy‘s opening a Broadway landmark, but there was more. Others present that night wouldn’t make it big until later, but the fact that they were there at all is enough to make you pray for time travel. For starters, there was the man who put together the pit orchestra: Ernest Loring “Red” Nichols, age 25, one of the busiest musicians in town. He was an accomplished cornetist who could play equally well “hot” and “straight”, and he had already made hundreds of Dixieland recordings for Brunswick Records, usually with an ad hoc band billed as Red Nichols and his Five Pennies. Playing Girl Crazy‘s lead was 19-year-old Ginger Rogers, fresh from making her Broadway debut in Top Speed and creating a sensation purring “Cigarette me, big boy” in her first movie, Young Man of Manhattan. She had two of Girl Crazy‘s most enduring songs, “Embraceable You” and “But Not for Me”, and by all accounts handled them quite nicely. But lacking what Cole Porter later called Ethel Merman’s “golden foghorn” voice, she had to stand helplessly by while Ethel stole her thunder night after night; it would take the intimacy of the movie camera to coax her star into full bloom. (And here’s a fun fact: During rehearsals one of her dance numbers was not working exactly right, so producers Alex A. Aarons and Vinton Freedley asked a dancing star they knew to step in and refine the choreography as a favor, and he coached Ginger on the routine in the lobby of the Alvin during rehearsals. You guessed it: It was Fred Astaire.)

Playing Girl Crazy‘s lead was 19-year-old Ginger Rogers, fresh from making her Broadway debut in Top Speed and creating a sensation purring “Cigarette me, big boy” in her first movie, Young Man of Manhattan. She had two of Girl Crazy‘s most enduring songs, “Embraceable You” and “But Not for Me”, and by all accounts handled them quite nicely. But lacking what Cole Porter later called Ethel Merman’s “golden foghorn” voice, she had to stand helplessly by while Ethel stole her thunder night after night; it would take the intimacy of the movie camera to coax her star into full bloom. (And here’s a fun fact: During rehearsals one of her dance numbers was not working exactly right, so producers Alex A. Aarons and Vinton Freedley asked a dancing star they knew to step in and refine the choreography as a favor, and he coached Ginger on the routine in the lobby of the Alvin during rehearsals. You guessed it: It was Fred Astaire.) Act II finds half the population of Custerville in San Luz. Danny finds Molly, bids her farewell and wishes her all the best with Sam; only after he leaves does she realize her true feelings for him, and now she fears the knowledge has come too late. But when she learns that Sam has registered them at the local hotel as husband and wife, she realizes what a cad he is and runs to Danny’s arms. Outraged, Danny blurts a threat against Sam that returns to bite him when Sam is assaulted and robbed and Danny is accused of the crime. Meanwhile, Kate confronts her cheating husband. Eventually — jeez, let’s cut to the chase — Gieber exposes Lank and his henchman Pete as the men who robbed Sam, Kate and Slick reconcile, Danny and Molly are reunited, and everybody presumably lives happily ever after back in Custerville.

Act II finds half the population of Custerville in San Luz. Danny finds Molly, bids her farewell and wishes her all the best with Sam; only after he leaves does she realize her true feelings for him, and now she fears the knowledge has come too late. But when she learns that Sam has registered them at the local hotel as husband and wife, she realizes what a cad he is and runs to Danny’s arms. Outraged, Danny blurts a threat against Sam that returns to bite him when Sam is assaulted and robbed and Danny is accused of the crime. Meanwhile, Kate confronts her cheating husband. Eventually — jeez, let’s cut to the chase — Gieber exposes Lank and his henchman Pete as the men who robbed Sam, Kate and Slick reconcile, Danny and Molly are reunited, and everybody presumably lives happily ever after back in Custerville.