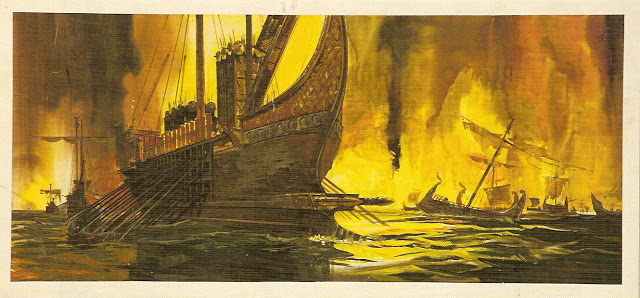

The good news about the Debbie Reynolds Auction is that there was an auction at all. She saved all these items from oblivion, and now they’re around for us to see. Debbie’s main interest was in the costumes, but there’s plenty of other stuff in her collection, like this concept painting from the 1963 Cleopatra. Just to illustrate how things can change from the early concept stages to final production…

…here’s how the battle of Actium looked on screen. The painting has a dramatic grandeur that contrasts sharply with the frame from the movie, which looks rather stodgy and pedestrian — and which, as it happens, is pretty much how the battle scene plays out in the movie itself. The same is true of other Cleopatra paintings on display in the catalogue; they show an energy and drive that survives only sporadically (and sometimes not at all) in the picture as it finally played in theaters.

My point is: It’s thanks to Debbie Reynolds that I’m even able to make this comparison. Maybe 20th Century Fox would have preserved these paintings and sketches. Maybe. But they didn’t. In 1971, reeling from the financial debacles of white elephants like Dr. Dolittle, Star! and Hello, Dolly! (and for that matter, Cleopatra, which eventually turned a decent profit, but too late to do any good), and with Star Wars still six years in the unseeable future, I’m sure Fox was only too happy to pick up a little spare change by getting rid of things like this. And Debbie Reynolds was there to take them for safe-keeping.

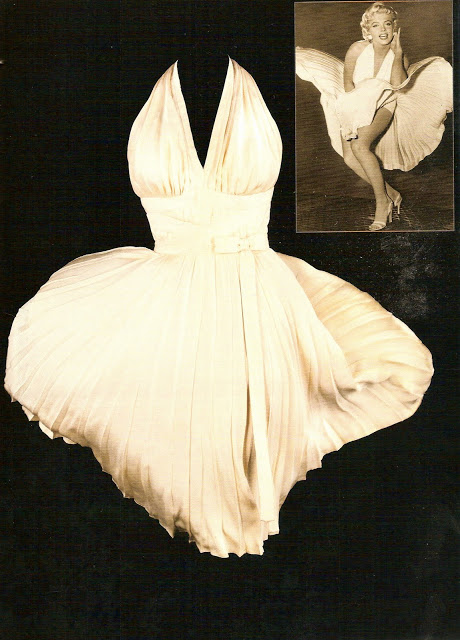

Now that Debbie is relinquishing her stewardship, we can reasonably assume that, whoever may wind up with this or that individual piece, the collection as a whole is safe for the forseeable future; nobody pays $5 million for a dress if they’re planning to leave it wadded up on the bottom shelf of the linen closet, or set it out on the curb next time the Salvation Army truck comes around. But where are the pieces going, and what precisely is going to become of them? Collectors can be a secretive and territorial bunch, not always quick to share. (And who can blame them? There are a lot of unscrupulous people out there; see here for a mention of the mysterious fate of Marcel Delgado’s production photos from The Lost World [’25] and King Kong [’33].) In the auction catalogue from Profiles in History, there’s a special plea from London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, asking for the loan of certain items in the collection for an exhibit on Hollywood costumes planned for October 2012 through January 2013. Debbie had promised curator Deborah Nadoolman Landis the use of any costumes she wanted — until the need to sell torpedoed the arrangement; it’ll be interesting to see if any of the new owners come through for the V&A.

So the Debbie Reynolds Collection existed in the first place, and it’s (most likely) safe now; that’s the good news. The bad news is that it won’t be a collection anymore. True, last month’s auction was only 587 lots out of whatever (5,000? 10,000?) is the total. Does Debbie intend to sell only enough to pay her outstanding debts, then start again at Square One with what’s left? Perhaps, but she certainly sounds as if she’s in the process of washing her hands of the whole kit and kaboodle. That’s perfectly understandable, but it’s still a shame.

I’ll miss having the opportunity to wander through the halls of the Debbie Reynolds Hollywood Movie Museum, and to go back as often as time and resources would allow; I suspect a single day wouldn’t have been enough to see it all. It’s comforting to know that these things are in the hands of people who’ll appreciate them, but having them all together in one place would have made the museum so much greater than the sum of its parts. As Virginia Postrel says, “To understand the past you need a large sample. Only then can you separate idiosyncratic variation from broad trends.”

I hinted at this idea in Part 1, when I suggested mix-and-matching a Cleopatra costume from the 1930s, ’40s and ’60s. How instructive it would have been to compare costumes from the 1925 and ’59 versions of Ben-Hur; or Mutiny on the Bounty ’35 and ’62; or how Adrian dressed Charles Boyer as Napoleon in Conquest (’37) vs. how Rene Hubert and Charles LeMaire dressed Marlon Brando in Desiree.

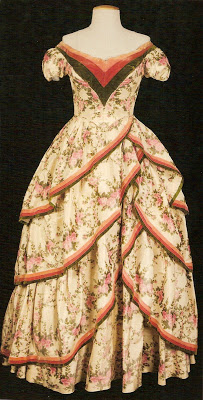

Or take this shot of Katharine Hepburn as Mary of Scotland (1936). You can see Mary of Scotland any time you like, and maybe you have. But while you were taking in the lavish settings and costumes captured by Joseph August’s richly atmospheric, deeply shadowed black-and-white cinematography, did it ever occur to you that the gown Kate is wearing here…

…really looked like this? We enter so completely into the world of any black-and-white movie (and arguably, Mary of Scotland is not one of the best) that we tend to forget that anyone ever thought of them in terms of color. We think, perhaps, that the studios wouldn’t spend money on something the camera wouldn’t see. But think that one through: The actors would see it. If Katharine Hepburn’s costume had really been composed of the shades of black and gray that we see on screen and in the picture above, she would surely have acted differently than she did in this sumptuous red and gold garment. And the camera would certainly have seen that.

This is one of the things I most noticed in looking through the costumes in the catalogue, the striking variety of color in costumes and set pieces built for black-and-white movies. That gold gown from DeMille’s Cleopatra is another example; it may look silver on screen, but no, it was gold.

Here’s yet another. It’s Tallulah Bankhead as Catherine the Great in A Royal Scandal (1945, begun by Ernst Lubitsch, who became ill during production and handed the direction off to Otto Preminger)…

…and here’s the dress she’s wearing, a “cognac silk

velvet two-piece period gown heavily jeweled with gold and white stones.” Talk about your Scarlet Empress! If you

Ctrl-click on the picture to open it in a new tab, then “plus” it up to full size, you can see the exquisite detail in the jeweling, which probably went all but unnoticed by audiences at the time. (You can, alas, also see that time has visited its ravages on the gown — mostly, no doubt, between 1945 and ’71, when Debbie acquired it from 20th Century Fox.) Bidding on this one started at $3,000 and it sold for

$7,000 plus another $1,610 for the house commission and sales taxes.

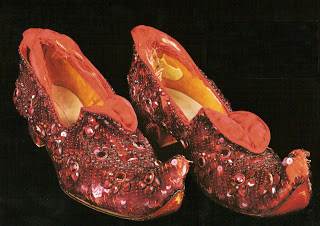

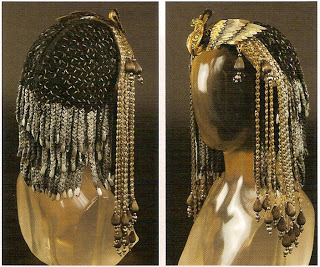

(And by the way, I said in Part 1 that I had no idea how much those Cleopatra costume pieces finally sold for. Well, now I know, thanks to the

icollector.com Web site:

Cleopatra [’34] gown, $40,000;

Cleopatra [’63] headdress, $100,000;

Caesar and Cleopatra wig and headband, $4,250. Maybe those “duelling Cleopatras” showed up after all. Also, Debbie’s

How the West Was Won gown brought $11,000. All prices are before 20 percent “buyer’s premium” and sales tax.)

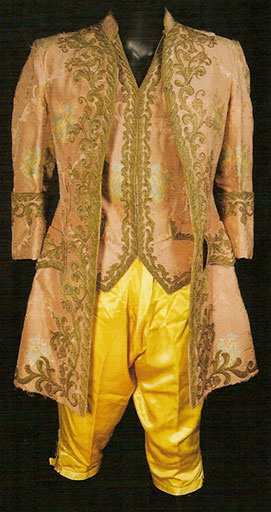

I could go on like this all day, but I’ll just give a few more examples, all from the same picture: Marie Antoinette (1938), Irving Thalberg’s last project, a vehicle for his wife Norma Shearer that was eventually released nearly two years after Thalberg’s death. Because it was Thalberg, and because he was doing it for Norma, no expense was spared. For starters, here’s a silk brocade jacket and vest with breeches (a pair of pink-and-brown ribboned shoes came with) for John Barrymore as King Louis XV…

…and here’s a wool coat with black velvet buttons for Tyrone Power as Count Axel de Fersen, the would-be rescuer of the doomed Louis XVI (Robert Morley) and his queen…

…while here’s a tunic worn by a servant attending the king at a royal ball. This costume, mind you, worn by a nameless extra whose own mother probably didn’t notice or recognize him.

These three samples alone — and the catalogue has eight more from the same picture — bear witness to the fact that the set of Marie Antoinette must have been an absolutely intoxicating riot of color. It makes us wonder what the movie might have looked like if Technicolor had been available (well, technically it was, but MGM was still timid about using it). Even more than that, it makes me (at least) think what an absolute Wonderland the set of Marie Antoinette must have been. Can you imagine? Well, you’ll have to, because you’ll probably never see these costumes all together in the same place again.

That, again, is the bad news of the Debbie Reynolds Auction: the opportunity to browse through these exhibits is in all likelihood slipping away from us forever. They’re all safe enough from outright destruction, no doubt, but they’ve been spirited away God knows where, to some private mansion or mountaintop retreat or private hall or atrium or display case, to be shared, if at all, with only a small circle of friends.

That’s why I’m glad I ordered my own copy of Profiles in History’s catalogue, even though my vague ideas about going to the auction or putting in some bids never went anywhere. And it’s why I plan to get a copy of the next edition in December (who knows, by then I may even be able to bid on something). The catalogue is like a souvenir book from the gift shop of the Museum That Never Was, a memento of the last time these exhibits were all under one roof — something I can leaf through at my leisure and pretend that I actually spent a day or two in the Debbie Reynolds Hollywood Movie Museum and saw all this myself first-hand.

If you’re interested in a catalogue of your own, you can (at least as of this date) order it here from Profiles in History. If you don’t want to pay the $39.95 — and don’t mind not getting the quality high-gloss paper it’s printed on — you can even download the catalogue for free on PDF. But be warned: It’s 312 pages and will probably take quite a while to download (and even longer to print), and it’ll probably take up quite a chunk of your hard drive when it gets there.