Geraldine Farrar was not the first star to occupy the M.J. Moriarty deck’s 3 of Hearts; that distinction (if Cliff Aliperti’s guess at the deck’s provenance is correct) belongs to Cleo Madison. But Ms. Farrar is the only Metropolitan Opera star in the deck. Other great singers would make the transition from Met to movies, but not until the sound era; and while some (Lawrence Tibbett, Grace Moore, Lily Pons, Maria Callas) would be more successful than others (Kirsten Flagstad, Luciano Pavarotti), only Geraldine Farrar managed to become a movie star without ever once depending upon her voice to get her there.

No wonder. She was a natural actress without a trace of self-consciousness, and the camera loved loved loved her. The picture on the card isn’t the most flattering, with that hairstyle like a leather aviator’s helmet, but you can see what I mean, especially with those enormous, all-seeing eyes — they make you want to glance over your right shoulder to see what she finds so fascinating and amusing; not even that huge corsage can pull your attention away from her eyes for very long.

Here’s another look at those eyes, this time smoldering and looking straight into your own. The portrait is by the German painter Friedrich August von Kaulbach (1850-1920), and is now part of the Geraldine Farrar Collection in the Music Division of the Library of Congress. It was probably painted in late 1901 or early ’02, about the time the 19-year-old Geraldine created a sensation as Marguerite in Gounod’s Faust and became the toast of Berlin.

Here’s another look at those eyes, this time smoldering and looking straight into your own. The portrait is by the German painter Friedrich August von Kaulbach (1850-1920), and is now part of the Geraldine Farrar Collection in the Music Division of the Library of Congress. It was probably painted in late 1901 or early ’02, about the time the 19-year-old Geraldine created a sensation as Marguerite in Gounod’s Faust and became the toast of Berlin.And then, in 1915, yet another medium. Moving pictures came calling, in the form of Cecil B. DeMille and the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company. Lasky and DeMille had been making a go of their venture out in sleepy Hollywood, shooting in a converted barn at the corner of Vine and Selma Streets. I don’t know what prompted them to approach Farrar; perhaps they read the interview where she described herself not as a singer but “an actress who happens to be appearing in opera” and figured an actress in any other vehicle… Whatever the impetus, it was a masterstroke. Farrar agreed to work eight weeks during the Met’s off season, making three pictures for a fee of $35,000. The news, and the announcement that the diva’s first picture would be a silent version of her Met success Carmen, electrified the industry. The William Fox Co. was inspired to do a quickie knockoff Carmen with their house vamp Theda Bara (Fox’s picture went into release the day after DeMille’s Carmen but doesn’t seem to have cut very deeply into its business).

The DeMille-Lasky Carmen wasn’t planned as an adaptation of the opera; the work was still under copyright, and the proprietors were asking too much for the movie rights. Instead, DeMille and his scriptwriter brother William turned to Prosper Mérimée’s original novella, now in the public domain, which had a story much changed in the opera. Still, the opera was too familiar to ignore completely, so a musical score was commissioned adapting Bizet’s themes (Lasky could afford that much).

Before shooting on their big-money title, though, DeMille made a canny decision: he would shoot Farrar’s other two pictures (Temptation and Maria Rosa) first, just in case his leading lady needed a little experience to put her at ease in front of the camera. This was probably prudent, but it proved to be unnecessary; Geraldine Farrar took to movies like a duck to water. Here she is in Carmen’s classic pose — a cliché by now, but at that time you could hardly get away with leaving it out — the rose clenched in her teeth, lasciviously eying the unfortunate Don Jose (Wallace Reid), whom she intends to seduce to help her smuggler cohorts.

And here she is again, assuring her gypsy confederate (Horace B. Carpenter) that the trap is ready to be sprung. As DeMille biographer Scott Eyman observes, Farrar wasn’t exactly beautiful, but she was alluring. Her Carmen moves like a cat, slinky, self-assured and radiating a confident, even aggressive sexuality. (Apparently in real life, too; Crown Prince Wilhelm wasn’t the only name linked romantically with hers. While at the Met she carried on a torrid six-year affair with conductor Arturo Toscanini that ended only when she gave him an ultimatum: leave your wife or else. The maestro abruptly resigned from the Met and beat a hasty retreat back to Italy, wife and family in tow.)

And here she is again, assuring her gypsy confederate (Horace B. Carpenter) that the trap is ready to be sprung. As DeMille biographer Scott Eyman observes, Farrar wasn’t exactly beautiful, but she was alluring. Her Carmen moves like a cat, slinky, self-assured and radiating a confident, even aggressive sexuality. (Apparently in real life, too; Crown Prince Wilhelm wasn’t the only name linked romantically with hers. While at the Met she carried on a torrid six-year affair with conductor Arturo Toscanini that ended only when she gave him an ultimatum: leave your wife or else. The maestro abruptly resigned from the Met and beat a hasty retreat back to Italy, wife and family in tow.)

Carmen was a big hit for the Lasky Co., in both money and prestige. Not since the aging Sarah Bernhardt hobbled around on her wooden leg in Queen Elizabeth had a star of such international magnitude graced a movie screen. And it must be said, whatever the Great Sarah’s power on stage, she had hardly a tenth of Farrar’s instinctive understanding of movie acting. By the time the picture was released — on October 31, 1915 — Farrar had returned to the Met; the other pictures she had shot that summer were spaced out for release the rest of the season, Temptation at the end of December and Maria Rosa at the beginning of May 1916.

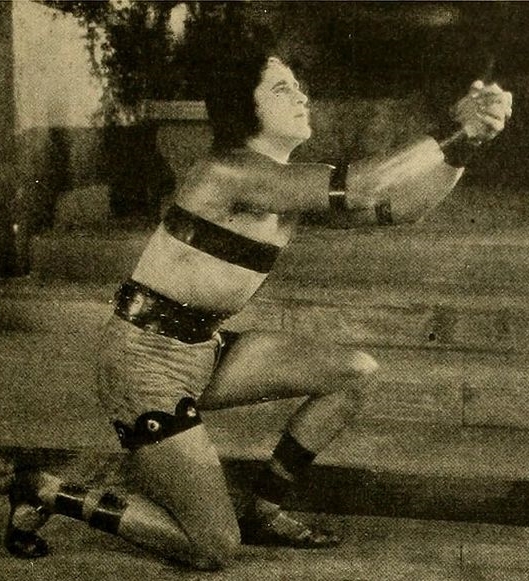

The Woman God Forgot wasn’t released until 1917; the big money picture for ’16 was Joan the Woman. DeMille and Macpherson drew a direct parallel between the Hundred Years War and the war then raging in Europe, telling the story of Joan’s battle for France within a framing story of an English officer in the trenches of the Great War (also played by Wallace Reid) who takes heart from Joan’s devotion (and attains a similar shall-not-have-died-in-vain martyrdom under the barbed wire). This publicity still was presumably approved for release by DeMille and Lasky, but unfortunately it isn’t terribly becoming to Ms. Farrar; granted, she was some years over-age (and some pounds overweight) for the role, but in the finished picture she never looks quite as tomboy-silly as she does here.

The Woman God Forgot wasn’t released until 1917; the big money picture for ’16 was Joan the Woman. DeMille and Macpherson drew a direct parallel between the Hundred Years War and the war then raging in Europe, telling the story of Joan’s battle for France within a framing story of an English officer in the trenches of the Great War (also played by Wallace Reid) who takes heart from Joan’s devotion (and attains a similar shall-not-have-died-in-vain martyrdom under the barbed wire). This publicity still was presumably approved for release by DeMille and Lasky, but unfortunately it isn’t terribly becoming to Ms. Farrar; granted, she was some years over-age (and some pounds overweight) for the role, but in the finished picture she never looks quite as tomboy-silly as she does here.In fact, it was in working on Joan the Woman that Farrar demonstrated the quality that DeMille, throughout his career, would especially prize among his actors: absolute fearlessness. Well, not absolute; she was actually afraid of horses and had to be doubled in many of her riding scenes. But fearless nevertheless; you can see it in the battle scenes, as she strides resolutely in full armor (only without that dear little pleated skirt) among the flailing swords, maces and pikestaffs.

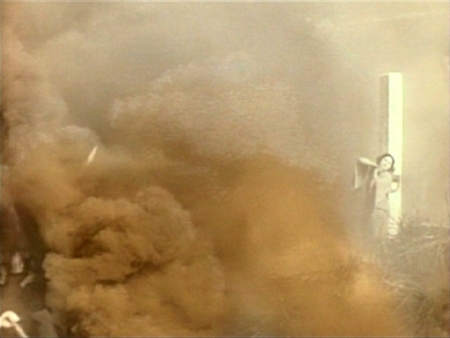

You can particularly see it in the scene of Joan’s execution at the stake, one of the most horrific scenes of the silent era, all the more effective for the stencil-tinting process that colored the flames of her pyre. Looking at a single frame, this closeup might look easy to fake, and it probably would be, but believe me, the flames in action look a lot closer and more dangerous than they do here. But if this shot of Joan appealing to her saints at the moment of death doesn’t convince you Geraldine Farrar was a real game ‘un…

…then how about this?…

…or this?

As Scott Eyman says, “How Farrar managed to survive without third degree burns or, at the very least, smoke inhalation remains a mystery.”

Alas, the honeymoon with Lasky and DeMille did not last, chiefly because of the honeymoon with Lou Tellegen. The Dutch-born Tellegen had come to America in 1910 at 29, as leading man (and offstage consort) to Sarah Bernhardt. After marrying Farrar in 1916, when she returned to Hollywood he began throwing his weight around and interfering in her films. To keep him out of their hair (and hers), DeMille and Lasky allowed him to direct a picture, What Money Can’t Buy. When they judged that one to be a dog — along with another, The Things We Love — Tellegen got his nose bent out of shape, and Farrar (out of what she later ruefully called “wifely loyalty”) sided with him. Both of them left the Lasky Co. and signed with Samuel Goldwyn.

Alas, the honeymoon with Lasky and DeMille did not last, chiefly because of the honeymoon with Lou Tellegen. The Dutch-born Tellegen had come to America in 1910 at 29, as leading man (and offstage consort) to Sarah Bernhardt. After marrying Farrar in 1916, when she returned to Hollywood he began throwing his weight around and interfering in her films. To keep him out of their hair (and hers), DeMille and Lasky allowed him to direct a picture, What Money Can’t Buy. When they judged that one to be a dog — along with another, The Things We Love — Tellegen got his nose bent out of shape, and Farrar (out of what she later ruefully called “wifely loyalty”) sided with him. Both of them left the Lasky Co. and signed with Samuel Goldwyn.

Working her customary off-season shifts, Farrar made six pictures for Goldwyn (three co-starring Tellegen). When Goldwyn complained that her pictures were not doing well, she suggested (with no hard feelings) that they cancel the remaining two years of her contract. She left movies for good in 1920, though she appears to have remained in the M.J. Moriarty deck until it ceased production — perhaps in the hope that she might return to the screen; anyhow, it was back to the Metropolitan Opera, where she retired amid great fanfare in 1922 at the age of 40.

The marriage to Lou Tellegen (her only one, the second of four for him) suffered from his chronic infidelities and succumbed to divorce in 1923. Tellegen himself came to a sorry end in 1934, a month short of his 53rd birthday. By then he had lost his looks (to a combination of age and facial injuries in a fire) and his career. He was ailing (it was cancer, but he wasn’t told). In 1931 he had published an autobiography, Women Have Been Kind, essentially a long boast about his sexual conquests that made him widely despised as a kiss-and-tell cad. (That year, the old Vanity Fair magazine had spotlighted him in their monthly “Nominated for Oblivion” feature, referring to his memoir as Women Have Been Kind [of Dumb].) Now, three years later, he elected himself to the oblivion Vanity Fair had nominated him for: While visiting friends in Hollywood, he locked himself in the bathroom, stood naked before the mirror, stabbed himself seven times with a pair of sewing scissors, and bled to death over an array of his clippings he had strewn on the floor. Approached by a reporter for a comment, Geraldine Farrar said, “Why should that interest me?”

What might have been if Geraldine Farrar had not joined in Lou Tellegen’s falling-out with Cecil B. DeMille is a tantalizing question mark. Even more tantalizing is the thought of how her career might have gone if she’d been born 20 years later, if she had made that hit in Berlin in 1921 instead of 1901. Then, when Hollywood went ransacking New York for musical talent during the sound revolution, she would have been about the age she is here, when she created the role of the Goose-Girl in Humperdinck’s Königskinder (The King’s Children) at the Met in 1910. Jeanette MacDonald and Irene Dunne, among others, may have had reason to be grateful that they never had to deal with any competition frrom Geraldine Farrar.

What might have been if Geraldine Farrar had not joined in Lou Tellegen’s falling-out with Cecil B. DeMille is a tantalizing question mark. Even more tantalizing is the thought of how her career might have gone if she’d been born 20 years later, if she had made that hit in Berlin in 1921 instead of 1901. Then, when Hollywood went ransacking New York for musical talent during the sound revolution, she would have been about the age she is here, when she created the role of the Goose-Girl in Humperdinck’s Königskinder (The King’s Children) at the Met in 1910. Jeanette MacDonald and Irene Dunne, among others, may have had reason to be grateful that they never had to deal with any competition frrom Geraldine Farrar.

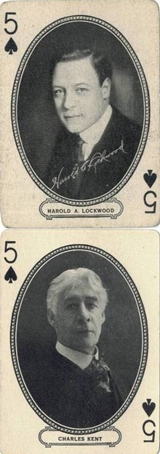

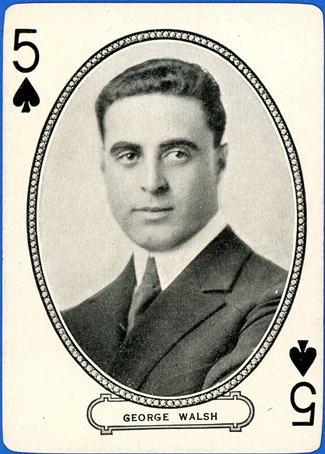

But back to our subject. Born in 1889, George Frederick Walsh followed his older brother Raoul (né Albert Edward) into pictures in the mid-1910s, having originally planned to be an attorney (he attended, however briefly, Fordham and Georgetown). He also attended New York’s High School of Commerce, where he graduated in 1911, and where he was a versatile athlete: baseball, track, cross country, swimming, rowing. This experience would stand him in good stead, at least in the Hollywood short run — certainly better than whatever he learned about commerce or pre-law.

But back to our subject. Born in 1889, George Frederick Walsh followed his older brother Raoul (né Albert Edward) into pictures in the mid-1910s, having originally planned to be an attorney (he attended, however briefly, Fordham and Georgetown). He also attended New York’s High School of Commerce, where he graduated in 1911, and where he was a versatile athlete: baseball, track, cross country, swimming, rowing. This experience would stand him in good stead, at least in the Hollywood short run — certainly better than whatever he learned about commerce or pre-law. George did get his first breaks in Reliance-Mutual pictures directed by Raoul and others, moving up the cast list till he was top-billed, and first drawing the eye of Variety’s reviewer in Raoul’s Blue Blood and Red (1916): “The kid is clever…a fine, manly looking chap, full of athletic stunts…” By this time, both Raoul and George were working for William Fox, and soon George worked again for D.W. Griffith. Here he is as the Bridegroom of Cana in the Judean Story section of Intolerance, receiving the bad news that the wine supply has run out. With him are 17-year-old Bessie Love (still several years from her own stardom) as the Bride of Cana and William Brown as the father of the bride.

George did get his first breaks in Reliance-Mutual pictures directed by Raoul and others, moving up the cast list till he was top-billed, and first drawing the eye of Variety’s reviewer in Raoul’s Blue Blood and Red (1916): “The kid is clever…a fine, manly looking chap, full of athletic stunts…” By this time, both Raoul and George were working for William Fox, and soon George worked again for D.W. Griffith. Here he is as the Bridegroom of Cana in the Judean Story section of Intolerance, receiving the bad news that the wine supply has run out. With him are 17-year-old Bessie Love (still several years from her own stardom) as the Bride of Cana and William Brown as the father of the bride. “Walsh is in his glory scaling walls, climbing trees, foiling cops, etc. There are a couple of corking fights where he handles anywhere from a dozen to twenty opponents at a time”; From Now On (’20), “What may be held up for approval is the hard work which George Walsh invests in it.” The image conjured up from these reviews is a series of lightweight adventures distinguished by George’s prowess; as brother Raoul, who directed From Now On, said years later, “Well, anything with him wouldn’t be too heavy.”

“Walsh is in his glory scaling walls, climbing trees, foiling cops, etc. There are a couple of corking fights where he handles anywhere from a dozen to twenty opponents at a time”; From Now On (’20), “What may be held up for approval is the hard work which George Walsh invests in it.” The image conjured up from these reviews is a series of lightweight adventures distinguished by George’s prowess; as brother Raoul, who directed From Now On, said years later, “Well, anything with him wouldn’t be too heavy.” Then came what looked like the break of a lifetime: George Walsh was chosen by writer June Mathis to play the title role in Metro’s screen adaptation of Ben-Hur, to be shot on location in Rome. The role was coveted by every actor in movies except Jackie Coogan. The most popular choice, Rudolph Valentino, was out of play because of a contract dispute with Famous Players-Lasky; until they settled their differences, the studio wasn’t about to let him work for anyone else. Mathis ordered tests, dozens of them, and Walsh won out. In his recounting of the Ben-Hur production in

Then came what looked like the break of a lifetime: George Walsh was chosen by writer June Mathis to play the title role in Metro’s screen adaptation of Ben-Hur, to be shot on location in Rome. The role was coveted by every actor in movies except Jackie Coogan. The most popular choice, Rudolph Valentino, was out of play because of a contract dispute with Famous Players-Lasky; until they settled their differences, the studio wasn’t about to let him work for anyone else. Mathis ordered tests, dozens of them, and Walsh won out. In his recounting of the Ben-Hur production in

And so did Charlotte. Somebody made up a nursery rhyme:

And so did Charlotte. Somebody made up a nursery rhyme:

He may have had other effects on her as well, and that possibility came to light only after the evening of Wednesday, February 1, 1922. On that night, sometime after 7:45 p.m., in the living room of this bungalow at 404-B Alvarado Street in Los Angeles, somebody stood behind William Desmond Taylor and shot him dead with a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson revolver.

He may have had other effects on her as well, and that possibility came to light only after the evening of Wednesday, February 1, 1922. On that night, sometime after 7:45 p.m., in the living room of this bungalow at 404-B Alvarado Street in Los Angeles, somebody stood behind William Desmond Taylor and shot him dead with a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson revolver.

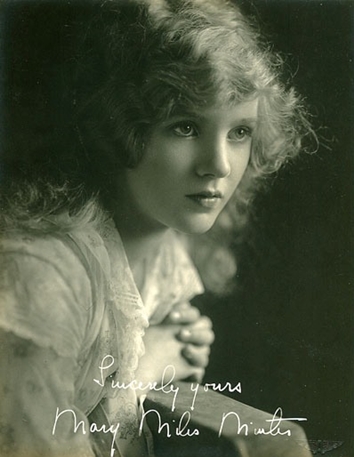

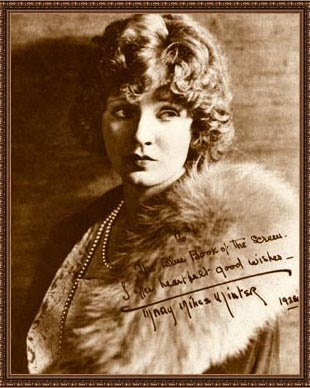

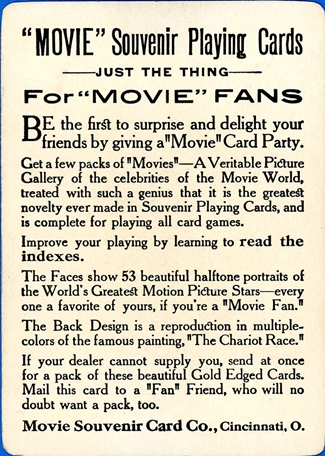

Try to imagine a time when a deck of cards with movie star pictures was a novelty. It’s not easy, is it? We can hardly even imagine a time when a movie star was such a novelty that the word “movie” itself was in quotes. But here it is, courtesy of one M.J. Moriarty and the Movie Souvenir Card Co. of Cincinnati, Ohio.

Try to imagine a time when a deck of cards with movie star pictures was a novelty. It’s not easy, is it? We can hardly even imagine a time when a movie star was such a novelty that the word “movie” itself was in quotes. But here it is, courtesy of one M.J. Moriarty and the Movie Souvenir Card Co. of Cincinnati, Ohio.

Von Wagner painted at least three versions of the painting, the first one in 1873 for the Vienna Exposition. A second version went on display at Philadelphia’s Centennial Exposition in 1876, and another — or perhaps the same one — at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The painting sparked a national craze, with etchings and lithograph prints for sale everywhere. Contrary to what some have said, it does not reproduce a scene from Ben-Hur, which wasn’t published until 1880; indeed, the painting and its pop-culture clones may have inspired Gen. Lew Wallace to include such a scene in his novel. In point of fact, the full title of the work is “Chariot Race in the Circus Maximus, Rome, in the Presence of the Emperor Domitian”, which would have been several decades after Judah Ben-Hur and Messala had their fateful showdown in Antioch’s Circus Maximus. Only one of von Wagner’s versions of the painting is known to survive; it hangs today in the Manchester Art Gallery in England.

Von Wagner painted at least three versions of the painting, the first one in 1873 for the Vienna Exposition. A second version went on display at Philadelphia’s Centennial Exposition in 1876, and another — or perhaps the same one — at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The painting sparked a national craze, with etchings and lithograph prints for sale everywhere. Contrary to what some have said, it does not reproduce a scene from Ben-Hur, which wasn’t published until 1880; indeed, the painting and its pop-culture clones may have inspired Gen. Lew Wallace to include such a scene in his novel. In point of fact, the full title of the work is “Chariot Race in the Circus Maximus, Rome, in the Presence of the Emperor Domitian”, which would have been several decades after Judah Ben-Hur and Messala had their fateful showdown in Antioch’s Circus Maximus. Only one of von Wagner’s versions of the painting is known to survive; it hangs today in the Manchester Art Gallery in England.

In 1937, Capra gave Warner the opportunity to deliver probably his best screen performance. The picture was Lost Horizon, from James Hilton’s utopian romance about a group of refugees from war-torn “civilization” who find themselves in the remote Himalayan paradise of Shangri-La. Warner (here with Isabel Jewell, Edward Everett Horton, Ronald Colman and Thomas Mitchell) played Chang, their mysterious escort from the snowbound wreck of their plane to the Edenic Valley of the Blue Moon, and their host after they arrive. Endlessly cordial, welcoming and polite, he nevertheless is inscrutably vague about when and how they will ever be able to return to their homes. Warner got an Oscar nomination as best supporting actor, but he didn’t win; he lost out to Joseph Schildkraut as Alfred Dreyfus in Warner Bros.’ The Life of Emile Zola. That’s a worthy performance, but I’m not at all sure the Academy made the right call. H.B. Warner’s other pictures for Capra were You Can’t Take It with You (1938), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939, as the Senate majority leader) and Here Comes the Groom (1951).

In 1937, Capra gave Warner the opportunity to deliver probably his best screen performance. The picture was Lost Horizon, from James Hilton’s utopian romance about a group of refugees from war-torn “civilization” who find themselves in the remote Himalayan paradise of Shangri-La. Warner (here with Isabel Jewell, Edward Everett Horton, Ronald Colman and Thomas Mitchell) played Chang, their mysterious escort from the snowbound wreck of their plane to the Edenic Valley of the Blue Moon, and their host after they arrive. Endlessly cordial, welcoming and polite, he nevertheless is inscrutably vague about when and how they will ever be able to return to their homes. Warner got an Oscar nomination as best supporting actor, but he didn’t win; he lost out to Joseph Schildkraut as Alfred Dreyfus in Warner Bros.’ The Life of Emile Zola. That’s a worthy performance, but I’m not at all sure the Academy made the right call. H.B. Warner’s other pictures for Capra were You Can’t Take It with You (1938), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939, as the Senate majority leader) and Here Comes the Groom (1951).

H.B. Warner’s final screen appearance was a poignant one. He was approaching 80 and living at the Motion Picture Country Home in Woodland Hills in 1955 when the call came from his old friend Cecil B. DeMille. DeMille was planning a massive spectacle expanding the Biblical section of his 1923 hit The Ten Commandments, and he had a part for H.B. if he felt up to it. The role was identified in the script as “Amminadab”, an aging Israelite setting out on the Exodus from Egypt, even though he knows he’ll never see the Promised Land — indeed, probably won’t live out the day. The actor carrying him in this shot, Donald Curtis, remembered that Warner weighed no more than a child, and carrying him wasn’t merely in the script, it was a necessity: “It was clear H.B. couldn’t walk — could barely breathe.” He had come to the set in an ambulance and lay on a stretcher, breathing through an oxygen mask, until the cameras were ready to roll. In the script, he had a rather complex speech adapted from Psalm 22, but he couldn’t manage it, so DeMille told him to say whatever he wanted, and Curtis and Nina Foch would work with it. H.B. Warner’s last words in his 137th movie, after 53 years as an actor, were: “I am poured out like water, my strength dried up into the dust of death.”

H.B. Warner’s final screen appearance was a poignant one. He was approaching 80 and living at the Motion Picture Country Home in Woodland Hills in 1955 when the call came from his old friend Cecil B. DeMille. DeMille was planning a massive spectacle expanding the Biblical section of his 1923 hit The Ten Commandments, and he had a part for H.B. if he felt up to it. The role was identified in the script as “Amminadab”, an aging Israelite setting out on the Exodus from Egypt, even though he knows he’ll never see the Promised Land — indeed, probably won’t live out the day. The actor carrying him in this shot, Donald Curtis, remembered that Warner weighed no more than a child, and carrying him wasn’t merely in the script, it was a necessity: “It was clear H.B. couldn’t walk — could barely breathe.” He had come to the set in an ambulance and lay on a stretcher, breathing through an oxygen mask, until the cameras were ready to roll. In the script, he had a rather complex speech adapted from Psalm 22, but he couldn’t manage it, so DeMille told him to say whatever he wanted, and Curtis and Nina Foch would work with it. H.B. Warner’s last words in his 137th movie, after 53 years as an actor, were: “I am poured out like water, my strength dried up into the dust of death.”