(With Apologies to Betty Comden and Adolph Green)

Los Angeles Times, March 25, 1928

Hollywood had two Rex Ingrams. Maybe someday I’ll write about the fine African American actor who played De Lawd in The Green Pastures, Lucifer Jr. in Cabin in the Sky and the Genie in 1940’s The Thief of Bagdad. But today I’m writing about the other Rex Ingram, who was born Reginald Ingram Montgomery Hitchcock in Dublin, Ireland on January 15, 1893.

I’ve been wrestling with this post much too long, trying to get some feeling for what this man was like beyond what we can see in his movies: an artist’s sense of composition, a tasteful eye for the telling detail, a delicate touch with actors, and a sure hand with both intimacy and epic sweep.

There’s only one biography of him, Rex Ingram: Master of the Silent Cinema by the late Liam O’Leary, and unfortunately it’s not much help. I know it sounds presumptuous for an armchair historian like me to pass judgment on a man like O’Leary — actor, director, archivist, official with both the Irish Film Society and London’s National Film Archive. But the fact is, his biography of Ingram is long on facts and short on insight, and it raises more questions than it answers.

Did Ingram ever graduate from Yale, where he studied sculpture? Michael Powell, whom Ingram inspired to become a movie director himself, says Ingram was a Yale grad, but O’Leary’s book isn’t clear. If Ingram didn’t graduate, did he drop out to work in pictures for the Edison Company, or did he flunk out and turn to pictures when he needed a job? He was obviously intelligent even in his youth, but he wouldn’t be the smartest student who ever grew bored and careless in his studies. Either way, O’Leary doesn’t say; one moment Ingram is at Yale, the next at Edison.

We know Ingram loathed Louis B. Mayer (he was neither the first nor the last to do that), and seethed when Mayer became his boss (Ingram had been Metro’s star director before the merger with Goldwyn and Mayer that formed MGM). But why? Given the effect on Ingram’s career, and possibly on Hollywood itself, it would be useful to have more of an inkling why Ingram couldn’t work with Mayer while directors like Clarence Brown and Sidney Franklin could.

Did Ingram ever convert to Islam, or didn’t he? It’s reported in Wikipedia that he did, along with a claim that he co-directed the silent Ben-Hur (which he didn’t). O’Leary cites the periodic allegations, and Ingram’s demurrals, then finally concludes “there may have been something to it.” A definite maybe.

Most frustrating of all, what exactly was Ingram’s relationship with June Mathis? This remarkable woman was one of the earliest power figures as Hollywood entered the 1920s. A writer with ambitions to produce, she went on to do just that (or “supervise,” as the jargon of the day had it) and might have risen even higher if she hadn’t died suddenly of a heart attack in 1927, age 40 (or 38, or 35, depending on whom you believe as to when she was born). There were rumors at the time that Mathis and Ingram were romantically involved, and that he threw her over when he eloped with Alice Terry during shooting of The Prisoner of Zenda in 1921. If true, that could explain the alienation between them that festered after The Conquering Power that same year, causing Ingram later to miss out on his dream project, Ben-Hur, when production supervisor Mathis pointedly gave the director’s megaphone to somebody else.

But there’s an alternate explanation, too: that the two clashed over Ingram’s direction of Mathis’s protege Rudolph Valentino in Conquering Power, the follow-up to The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, the picture in which she and Ingram had launched Valentino to stardom. Mathis believed that Ingram was being high-handed with Valentino, while Ingram believed that he was directing the same way he always had, but that Valentino’s sudden fame had gone to his head and made him too big for his britches. Either story makes sense — the woman scorned or artistic differences — and it would be nice to know which is closer to the truth.

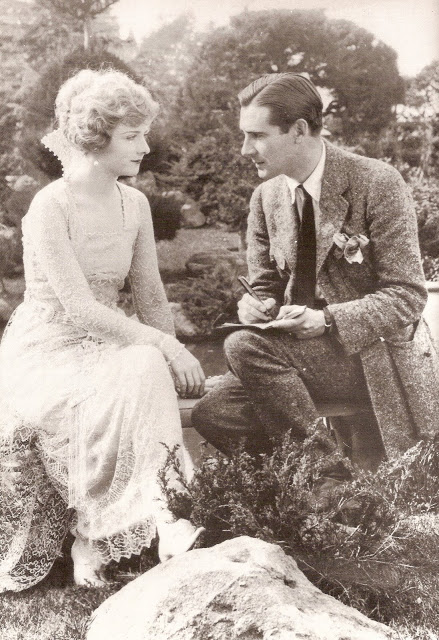

|

| Ingram and Alice Terry at the time of their marriage in November 1921 |

Liam O’Leary became good friends with Alice Terry, Ingram’s widow, and she was still alive in 1980 when O’Leary’s biography of Ingram was published. I suppose it’s only natural that he might be too tactful to explore any rumors about Terry’s late husband and a woman dead more than fifty years, but you don’t dispel gossip by ignoring it. O’Leary does concede that Mathis may well have been in love with Ingram (as she clearly was with Valentino), but insists that Rex only had eyes for Alice; even Ingram’s first (apparently unhappy) marriage is dispensed with in two hasty paragraphs.

In any event, Mathis was there to give Ingram’s career a huge boost by choosing him to direct The Four Horsemen, her pet project at Metro, from the international bestseller by Vicente Blasco Ibañez. Ingram had been building a name for himself for some time, but that was the picture that catapulted him to Hollywood’s front rank.

Ingram began in movies in 1913 at the Edison Co. studio in the Bronx. He did a little bit of everything in those unregimented early days — advising on intertitles, set decoration, painting portraits of Edison’s prominent players, pitching in on scenario writing, and so forth. With his matinee-idol good looks (Erich von Stroheim said he looked like a Greek god), it was inevitable he’d end up on screen as well, but he was a self-conscious actor — and never much interested in that side of the camera anyway. After a few months at Edison he went to Vitagraph as an actor and writer for a year or so, then in June 1915 on to the Wm. Fox Film Corp. as a writer and assistant director. It was about this time that Rex Hitchcock dropped his last two names and became Rex Ingram for the rest of his life. After a year at Fox, he moved on to Carl Laemmle’s Universal, where he finally got his first opportunities to direct at the young age of 23 (like William Wyler nine years later). In 1917, When Uncle Carl moved his production operations to the new Universal City in Hollywood, Ingram went west as well.

It probably didn’t help his morale to return to Universal seeking his old job back, only to be told that the vacancy had been filled, and by the Vienna-born Erich von Stroheim — the “enemy” Ingram had gone off to fight. Stroheim went out of his way to be cordial when he found Ingram lurking around the set (“What’s that sonofabitch doing? He’s got my job!”); Stroheim brought out a bottle of scotch and after ten or twelve drinks “we were very palsy-walsy.” The friendship took hold and endured for the rest of Ingram’s life; Stroheim once called Ingram “the world’s greatest director.”

In short order Ingram’s health and his job prospects improved. He managed after all to pick up a couple of directing jobs for Universal (including helming a screen test for a hopeful newcomer named Rudolph Valentino, who impressed Ingram as having possibilities), then in late 1919 landed a directing berth at $600 a week with theater magnate Marcus Loew, who had just acquired the Metro Pictures Corporation to supply product for his chain of cinemas.

The other person, of course, was June Mathis. She had been impressed with Ingram’s work on his first two films at Metro and asked for him to direct The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, which she was shepherding to the screen after prodding Metro to acquire the rights. Spanish author Vicente Blasco Ibáñez’s novel had been a worldwide bestseller in 1918 and ’19, and rumor had it that Fox was willing to pay $75,000 for movie rights. Metro studio chief Richard Rowland, at Mathis’s urging, won the bid with a $20,000 advance against ten percent of the profits.

We may not know exactly why Ingram despised L.B. Mayer — their paths don’t seem to have crossed in Hollywood — but we know he did. Ingram had left for Tunisia an employee of the Metro Pictures Corporation; now suddenly he was working for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. He had a new clause inserted into his contract: he would answer to Marcus Loew and Nicholas Schenck, not Mayer; his pictures would have the billing, “Metro-Goldwyn presents a Rex Ingram production.” He literally did not want Mayer’s name mentioned in the same breath with his own.

With the MGM merger, Loew’s Inc. had inherited Ben-Hur, shooting in Mussolini’s Italy at the same time Ingram was in Tunisia with The Arab. By mid-1924 the Ben-Hur production had degenerated into a shambling fiasco (for the juicy, fascinating details, see Kevin Brownlow’s The Parade’s Gone By). Mayer and Irving Thalberg assessed the situation, and were appalled. June Mathis, Charles Brabin and leading man George Walsh were all summarily fired. And at this point, evidently, Rex Ingram missed out on directing his dream picture once again. O’Leary reports that Mayer invited Ingram to take over the production, “but Ingram made so many conditions that Mayer refused to consider them.” What conditions? For that matter, if Ingram was so depressed when he lost out the first time, why were there any conditions? I suspect one condition might have been that “Metro-Goldwyn” business; Ingram wanted Ben-Hur, but not if it was to be a Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer picture. Also, Ingram may have wanted to shoot at Victorine, while Mayer may already have decided to bring this runaway disaster home to Hollywood where he could keep an eye on it; besides, an epic like this could never be done at Ingram’s quaint little boutique studio on the Mediterranean coast.

This double miss is one of the great what-ifs of Hollywood. As good as the 1925 Ben-Hur is — and it’s very good indeed, far superior to its more famous remake — it surely would have been even better in Ingram’s hands, even if he’d had to make it without his alter ego John Seitz.

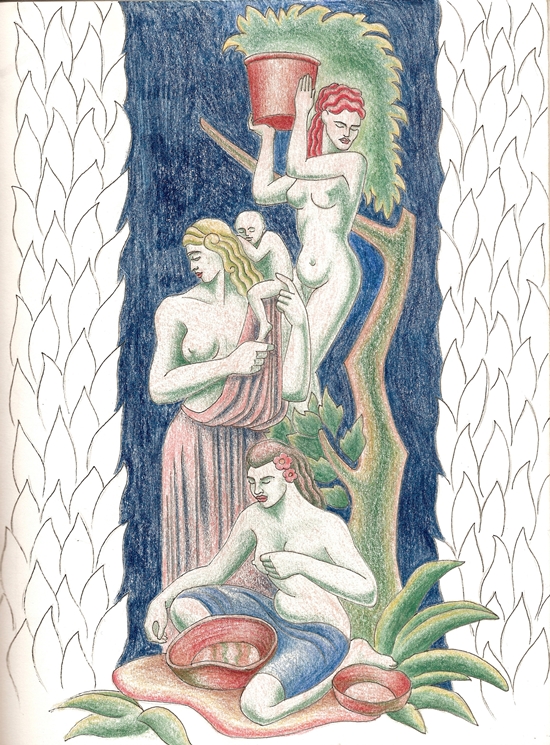

For a few years in the 1920s Ingram operated in a manner Stanley Kubrick would later duplicate (albeit for a much longer time), staying within his own workspace far from studio higher-ups, keeping his own counsel and pursuing his own course, telling the home office when he had a movie ready for them. After The Arab he made three more pictures for MGM — or rather, Metro-Goldwyn — Mare Nostrum (1926), from another Blasco Ibañez novel set during the Great War; The Magician (also ’26), from a bizarre story by Somerset Maugham, with stylistic elements that clearly influenced James Whale’s later Frankenstein pictures at Universal; and The Garden of Allah in 1927. This last picture completed his contract with Metro, and when Ingram refused to return to Hollywood to work, MGM declined to renew.

Meanwhile, Ingram had somehow managed to lose control of his Nice studios. He sued his French lawyer, claiming that the attorney had fraudulently maneuvered ownership of the studio away from him (and alleging that the studio manager had swiped documents from Ingram’s office that would prove his charge). The case dragged on until 1936, and Ingram lost every step of the way. His opponent was a powerful and influential man in French law and politics; Ingram may have come to reflect that he hadn’t left chicanery and the “inevitable scramble for power” behind in California after all.

After that there were only two more pictures, The Three Passions (’29) and Baroud (’32). His only talkie, Baroud was planned in English, French, Spanish and Arabic versions, but only the English and French were ever shot. Released in America as Love in Morocco, it was curtly dismissed by Variety as “A dull story, badly handled and acted.”

That has a certain how-the-mighty-have-fallen ring, doesn’t it? Ingram didn’t see it that way at the time, he simply moved on from what he’d been doing. He welcomed talkies (“Silent pictures are finished and a good thing too”), but visual artist that he was, was never entirely comfortable with them — understandably, being an American working in France with polyglot actors and crews. He basked a while on the beaches of Nice, sojourned in North Africa, where his affinity for Arab culture gave rise to those rumors that he had embraced Islam. While in Egypt, O’Leary reports, he contracted an unnamed illness that left him with high blood pressure for the rest of his life (which no doubt brought on his early death at 57 of a cerebral hemorrhage).

In 1936 Ingram and Alice Terry settled again in Hollywood, where he lived in modest comfort, writing two novels and several short stories, sculpting, painting, traveling occasionally (Hawaii, Mexico, London, Egypt), and perusing a succession of scripts forwarded to him by his old pal Eddie Mannix at MGM, just in case there was that one he simply had to direct. (In 1942, when he heard Paramount was planning to make For Whom the Bell Tolls, he was interested, but nothing ever came of it; another what-if.) And so it was on July 21, 1950, that the Fourth Horseman of the Apocalypse came for Rex Ingram himself.

Rex Ingram’s output was impressive while it lasted — 27 pictures in just under 16 years. Unfortunately, few of his pictures are readily available to help us appraise his full career. Many (if not all) of his pre-1920 pictures are lost forever, and others are preserved only in archives and seldom shown. Fortunately — and it is good fortune indeed — the handful to be found on home video are among his best, and preserve the record of a great director at the pinnacle of his career.

Rex Ingram’s output was impressive while it lasted — 27 pictures in just under 16 years. Unfortunately, few of his pictures are readily available to help us appraise his full career. Many (if not all) of his pre-1920 pictures are lost forever, and others are preserved only in archives and seldom shown. Fortunately — and it is good fortune indeed — the handful to be found on home video are among his best, and preserve the record of a great director at the pinnacle of his career.

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, make no mistake, is every bit the masterpiece it was in 1921, and can be shown today to anyone without explanation or apology — anyone, that is, who doesn’t blindly and rigidly refuse to abide silent movies. There’s a reason this one made a star of Valentino (it’s probably still his best performance), but he’s far from the only reason to see it, and not even the best reason at that. Alice Terry (not yet Ingram’s wife) is radiant as Valentino’s married lover, and veteran Joseph Swickard as Valentino’s father gives one of the great performances of the silent era; it is in fact Swickard who carries more of the film than any single player. And over it all is Ingram’s amazing command of pacing, epic sweep, and depth of emotion, while underpinning it is June Mathis’s literate distillation of Blasco Ibañez’s sprawling novel.

Scaramouche (available here in a gorgeous transfer from the Warner Archive) has nearly the epic sweep of Four Horsemen, and John Seitz’s camerawork is little short of astonishing. Rafael Sabatini’s novel is faithfully and intelligently followed (unlike the 1952 remake, which made major changes), and the settings, costumes and faces of the characters have the realism of a trip in a time machine to Revolutionary France.

The Prisoner of Zenda, at least in the version I’ve been able to track down, does murky damage to Seitz’s photography, but Ingram’s subtlety, eye for detail and sense of pace survive, as does Lewis Stone’s performance in the lead (Ronald Colman obviously emulated him in the 1937 remake) and Ramon Novarro’s delightful turn as the likeable villain Rupert of Hentzau.

In the final analysis — and I admit, this is the rankest barstool psychology — I think Rex Ingram was an artist who fought against the constraints of the nascent studio system without realizing how much its support and resources helped him achieve what he was after. He worked best at the controls of a well-oiled machine with a complement of crack mechanics who understood how the machine worked and where Ingram wanted it to go. At its best, that machine and that crew gave shape to what Michael Powell called “Rex’s extravagant dreams”; when the crew started to fall away and Ingram tried to do more of the work alone or with substitutes, then came what Powell in the same sentence called his “thundering mistakes”.

Ingram had Irish charm, but arrogance as well, and he made enemies as easily as friends (though not as often). When he fell out with June Mathis, I’m sure it never occurred to him that it might backfire later on. And when she was mulling who would direct Ben-Hur, I suspect he thought something like, I’m the best choice for this job and she knows it. When Mathis chose Charles Brabin, he probably thought Mathis was being petty and vindictive and — maybe even — just like a woman. This created such a disgust in him — that she would wound him and the picture, simply out of spite — that it drove him out of Hollywood altogether, as far as he could go and still breathe the air.

In Nice he found a studio where, he thought, he needn’t wrangle with or truckle to anyone, smaller and more manageable than the factories that were coalescing in Hollywood, more like the heady, footloose atmosphere at Edison and Vitagraph where he started, but better equipped and up to date. But there was still wrangling to be done, and what he thought of as truckling we might now call networking. Off there in the Mediterranean, to the moguls back in Hollywood he was out of sight, out of mind. MGM indulged him because his movies were good, even excellent. And while there were no more blockbusters like Four Horsemen, there were no calamities either; his pictures made money, and even the least successful (The Magician) broke even. But when his time-out was up and Ingram still wouldn’t come home and play well with others, Metro-Goldwyn and Mayer sighed and cut him loose. Ingram, for his part, shrugged and got on with his life.

Of course, I could be wrong.

Finally, two quotes. First, Grant Whytock, editor on eleven of Ingram’s best pictures: “Rex worked harder than anyone I’ve ever seen. He used to run to the set.”

And one more from Byron Haskin: “Ingram’s work forecast the coming of finesse in movies. I would rank Ingram as number one director, number one in the business. He had traces of sophistication that were not seen in films, that’s all there was to it. Films were just a child-like, fairy-tale quality about most of them; they were made to entertain, and that’s that. But Ingram got into nuances and values of the story, of the characters that — I don’t really know any other director who reached that deeply.”

And here’s a parting look at the Victorine Studios as Ingram knew them in 1928. They still stand, though much changed, having weathered bankruptcies, fires, and World War II. Hitchcock’s To Catch a Thief was shot there, and Truffaut’s Day for Night, and even Mr. Bean’s Holiday. They are now run by Euro Media Television, the name changed to Studios Riviera. Ownership of the property will revert to the City of Nice in 2018, at which time the property may be cleared, subdivided and redeveloped. Some people say the ghost of Rex Ingram still walks there. They say he doesn’t want the place to close.

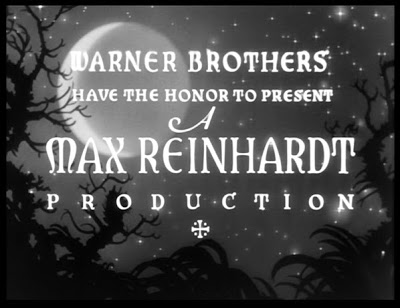

“Was Warner Bros.’ film the glorious climax of Shakespearean art,” asks Scott MacQueen in his commentary on the DVD of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, “or just another sign that the Day of the Locust was at hand?” It’s a good question, and I’ll address it in due course.

“Was Warner Bros.’ film the glorious climax of Shakespearean art,” asks Scott MacQueen in his commentary on the DVD of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, “or just another sign that the Day of the Locust was at hand?” It’s a good question, and I’ll address it in due course.

First, though, let’s take a look at the opening title that appears on the Midsummer screen. I wonder: Is this the only time the word “Brothers” was ever spelled out in a Warner Bros. picture? (They didn’t do it for Anthony Adverse, the studio’s big prestige spectacular of the following year.) Somehow it seems to lend an intimate touch, as if the title card were speaking for Harry, Albert and Jack Warner personally, not merely the corporate entity whose official name was “Warner Bros. Pictures.” At the same time, there’s an almost endearing air of self-conscious dignity about it. Deference too — notice that Max Reinhardt gets bigger billing than the brothers themselves.

Notice something else, the background. It’s an image that appears again early in the movie, as the scene shifts from Athens to the forest fairyland. There’s the moon exactly as it’s described by Hippolyta, Queen of the Amazons, “like to a silver bow/New-bent in heaven.” It’s the kind of touch that ruffled the feathers of some of the movie’s snootier critics (especially in Great Britain), a sign that (in their eyes) Shakespeare’s sublime poetry had been sullied by the over-literal hands of these impertinent, vulgar Yanks. A more charitable eye might have perceived that the artists and craftsmen behind the screen understood and honored that poetry, and were doing their best to render it faithfully in the visual medium that was their own area of expertise.

For the Hollywood Bowl production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream that so captivated Hal Wallis and thousands of other Angelenos, Reinhardt had moved away from the minimalist staging that he had been trending toward in Shakespeare’s forest revel (and which has more or less been followed ever since). In such a setting, a bare stage and simple green curtains would hardly do, so Reinhardt had transformed the play into a spectacular, awe-inspiring pageant. Or rather, transformed it back, for that was what the 19th century had seen in the play at least ever since 1843, when a German production in Potsdam first incorporated Felix Mendelssohn’s grandly romantic incidental music.

Scott MacQueen’s commentary on the DVD goes far to address the need for a full account of the making of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (though I still say it rates a book), but he offers only scattered details of the Bowl production which begot it. To my knowledge, no pictures from that staging are readily available, so I can’t address how the movie might have emulated or departed from it. There is, however, a certain semi-Wagnerian, almost Teutonic grandeur to the movie that is in keeping with what we know of Reinhardt’s style, and reviewers who saw his stage productions in L.A., New York and London recognized his touch on the screen. Whether direct credit for the final look of the movie goes to Prof. Reinhardt or to a combination of art director Anton Grot, set designer Harper Goff, costumer Max Ree, cinematographer Hal Mohr and editor Ralph Dawson (who won the movie’s other Oscar), it’s clear that the headline “A Max Reinhardt Production” was no empty boast.

The Hollywood Bowl had freed Reinhardt from the limitations of the ordinary proscenium stage. The movie screen freed him from the limitations of even that vast basin in the Hollywood Hills. As it happened, the camera ventured outside the sound stages only for this brief scene, where you can see the familiar hills of the Cahuenga Pass behind the studio’s backlot. But other freedoms came with the camera, and Reinhardt and co-director William Dieterle drew on the talents of Mohr and special effects team Byron Haskin, Fred Jackman and Hans Koenekamp to do things impossible on any stage.

The Hollywood Bowl had freed Reinhardt from the limitations of the ordinary proscenium stage. The movie screen freed him from the limitations of even that vast basin in the Hollywood Hills. As it happened, the camera ventured outside the sound stages only for this brief scene, where you can see the familiar hills of the Cahuenga Pass behind the studio’s backlot. But other freedoms came with the camera, and Reinhardt and co-director William Dieterle drew on the talents of Mohr and special effects team Byron Haskin, Fred Jackman and Hans Koenekamp to do things impossible on any stage. Like this, for instance. Here the followers of fairy queen Titania gather for their nightly revels, prancing, dancing, swirling and flying to the sprightly strains of Mendelssohn’s Scherzo as scored by Erich Wolfgang Korngold. (Korngold was imported by Reinhardt from their native Austria to arrange Midsummer‘s music; he would stay in Burbank to do other work for Warner Bros. Then, on the heels of Hitler’s annexation of Austria, Korngold would settle in Hollywood permanently, composing some of the greatest film scores of all time.) In the droll words of The New Yorker’s John Mosher, “The Reinhardt fairies flit over the treetops on escalators of moonshine, mists rise from the meadows and take the shapes of weird creatures of the night…” Shakespeare himself (as we can infer from the text of his plays) had a keen appreciation for the power of theatrical effects; would he not have reveled in these scenes as much as Titania’s fairies do? I believe he would have, and that anyone who thinks otherwise is a snob beyond redemption.

Like this, for instance. Here the followers of fairy queen Titania gather for their nightly revels, prancing, dancing, swirling and flying to the sprightly strains of Mendelssohn’s Scherzo as scored by Erich Wolfgang Korngold. (Korngold was imported by Reinhardt from their native Austria to arrange Midsummer‘s music; he would stay in Burbank to do other work for Warner Bros. Then, on the heels of Hitler’s annexation of Austria, Korngold would settle in Hollywood permanently, composing some of the greatest film scores of all time.) In the droll words of The New Yorker’s John Mosher, “The Reinhardt fairies flit over the treetops on escalators of moonshine, mists rise from the meadows and take the shapes of weird creatures of the night…” Shakespeare himself (as we can infer from the text of his plays) had a keen appreciation for the power of theatrical effects; would he not have reveled in these scenes as much as Titania’s fairies do? I believe he would have, and that anyone who thinks otherwise is a snob beyond redemption.

…minces…

…and pouts, in easily the worst performance of his career, and arguably one of the worst in Hollywood history. Powell was already chafing at his boy-tenor roles, sensing that the clock was ticking — on stage a male ingenue might keep it going until his grandkids were out of knee pants and pinafores, but in the movies it would never work, and at 30 Powell’s juvenile days were clearly numbered. Well then, playing Lysander in A Midsummer Night’s Dream was a heaven-sent opportunity for Powell to segue nimbly from squiring Ruby Keeler and Wini Shaw around Buzz Berkeley’s dance floors into the kind of roles where he could age with grace. But did he see it that way? He did not. Insisting he wasn’t “a Shakespearean actor,” he tried to dodge the role (some say “to his credit,” but I’d say it does him none; never mind “Shakespearean,” whatever that means; do you want to act or don’t you?). When the studio wouldn’t let him take a pass, he seems to have gone out of his way to prove how wrong they were. Obviously he didn’t think that one through; when the projector beam finally hit the screen in October 1935, it wasn’t Jack Warner or Hal Wallis up there with egg on his face. When Powell finally managed to carve out a new screen persona for himself in 1944’s Murder, My Sweet, I wonder: did he ever look back on the chance he had blown nine years earlier?

We can contrast Powell’s tantrum of a performance with another Midsummer actor who was miscast yet still managed to make it work: James Cagney. He’s the last actor you’d expect to play the lumpen dullard Nick Bottom, and he was apparently one of the last considered. Dieterle’s early notes mention Wallace Beery and W.C. Fields. Beery was a logical choice, if he could keep from dawdling through his lines and overdoing the neck-scratching mannerism he liked to use instead of acting — and if anyone on the set could have stood working with him (it certainly would have strained Anita Louise’s talent to the limit). Fields might have been fun, but the idea was a nonstarter — he was shooting David Copperfield over at MGM. Memos from Hal Wallis say what a “far-fetched” choice Cagney would be, and as late as the day before rehearsals started, contract player Guy Kibbee was slated for the role. But Reinhardt made an executive decision and Kibbee was out, Cagney in.

Fifty-two-year old Guy Kibbee would have been a comfortable choice for Bottom — a little old, maybe, but the right physical and character type — and he probably would have passed muster with the critics (except those in England who sniffed that there were just too damn many American accents in the cast). But Reinhardt was impressed with Cagney’s dynamism and the studio was comfortable with his box office clout (he did get top billing), so that was that. Cagney’s approach was straightforward — “The keynote,” he recalled decades later, “was the sonofabitch was a ham…he wanted to play all the parts…” He played Bottom as cocky and obnoxious rather than sluggish and obstinate; he made the character work for him, and made his performance work for Reinhardt and the movie. It’s not exactly the Bottom of Shakespeare, and in the movie it’s not entirely incongruous for Titania to fall for him, even crowned with a donkey’s head. But faced with the fait accompli of his casting, Cagney rolled up his sleeves and got to work. It was an attitude Dick Powell could have learned from, if he’d pulled in his lower lip long enough to take notice.

One facet of the movie that I’ve seen no comment on, but that keeps it living and breathing today, is its undercurrent of discreet eroticism. Nothing to put the bluenoses of the Hays Office out of joint, to be sure, but it’s there all the same. Here, for example, is the on-screen equivalent of that posed publicity shot of Titania and Bottom that I showed in Part 1. Not only is the pose more explicitly sexual, but so is the expression on Titania’s face. In the publicity still she stares blankly past Bottom’s snout, while here — in action, as it were — she gazes at him with a postcoital afterglow worthy of Scarlett O’Hara.

And here we are again with Hermia, as she contemplates eloping to beyond the forest with her true love Lysander. In 18-year-old Olivia de Havilland’s first screen performance, Hermia is proper and maidenly, but we see moments like this, flashes of the wanton under her decorous exterior. It makes the transition ring true later, as Puck’s mischievous love potion takes effect on Lysander, when Hermia becomes a snarling spitfire, seething with all the fury and sexual frustration of a woman scorned.

Notwithstanding the Neo-Victorian pageantry of the movie, there’s one way in which Reinhardt and Dieterle look not back to the past, but forward to later directors’ approach to A Midsummer Night’s Dream: they treat the quartet of young lovers not as the lyrical ideals they had become in the 19th century, but as foolish figures of fun, and the squabbling and bickering of this romantic quadrangle are some of the funniest scenes in the movie. Love’s unpredictable magic has turned them all into asses — a neat counterpoint to the story of Nick Bottom, where being changed into an ass unexpectedly turns him into a lover. Again, is that counterpoint explicitly to be found in Shakespeare? Perhaps not. But is it an astute comment on the intertwined stories of the Dream? Definitely. And it shows (again) an acute understanding of the material running all through the Warner lot in Burbank, not (as some critics then and now would have it) a blundering blindness to the beauty of what they were manhandling in their clumsy paws.

So returning to Scott MacQueen’s question — no, this was not the flowering of Shakespeare’s art, although it came closer to it than anyone could have expected. But “a sign that the Day of the Locust was at hand”? Hardly. For that, we need look no further than the 1930 Moby Dick, when Warner Bros. thoughtfully corrected the oversights of Herman Melville by providing Captain Ahab with a last name, a sweetheart, and a happy ending.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream may well be the most miraculous of those “miracle pictures” I wrote about before. Warner Bros. and Max Reinhardt undertook one of Shakespeare’s most beloved plays — not to “improve” or “correct” it, as Warners had tried with Moby Dick, but to fulfill it. Hal Wallis saw something at that amphitheater on Highland Avenue that struck him as worth putting on film, and whatever changes were wrought between the Bowl and Burbank, Wallis and his colleagues did their best to get it right. Let the salesmen worry about getting audiences into the theaters.

I conclude this tribute with a salute to three of the players from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the three members of the Hollywood Bowl cast who Max Reinhardt absolutely insisted must be included in the movie. By a happy coincidence, they are also the last three survivors of the principal players. Top to bottom: Mickey Rooney as Puck, Olivia de Havilland as Hermia, and Nini Theilade as chief fairy-in-waiting to Queen Titania.

Rooney and de Havilland hardly need any introduction. De Havilland, not only for her double-Oscar career but for her landmark lawsuit that eventually broke the studios’ iron slaveholder’s grip on their performing artists, may have proven to be Max Reinhardt’s most momentous contribution to movie history.

Nini Theilade, however, is a less familiar name. Born in Indonesia to Danish parents, she was 19 when she danced for Reinhardt at the Bowl, and for Dieterle and choreographer Bronislava Nijinska on the Warner Bros. sound stages. When Midsummer went from its road show to general release, 16 minutes were trimmed; since her performance was almost entirely danced, she was left with only a brief moment of dialogue with Rooney’s Puck. It took the restoration of the complete movie in 1994 to let us again see Mlle. Theilade’s full work, and appreciate her ethereal beauty and exquisite grace. She turned 95 on June 15, while de Havilland was 94 on July 1 and Rooney will turn 90 September 23. Continued long life to them all, and thanks.

UPDATE 9/5/16: Mickey Rooney passed away April 6, 2014, age 93. But I’m pleased to report that as of this date Ms. de Havilland and Mlle. Theilade are still with us, having turned (respectively) 100 on July 1 and 101 on June 15 of this year.

UPDATE 4/15/18: Mlle. Nini Theilade left us on February 13, 2018, just past the halfway mark to her 103rd birthday. Olivia de Havilland, 101, is now the last survivor of Warner’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream — and, in all likelihood, of the Golden Age of Hollywood.

UPDATE 8/11/20: And now, Olivia de Havilland is gone too, having passed away July 26, 2020, twenty-five days after her 104th birthday. May she, and the rest of the Midsummer cast, rest in peace, with the thanks of us all.

One night years ago I was showing a friend some scenes from the 1935 Warner Bros. movie of A Midsummer Night’s Dream — the gathering of the fairies, the magic woodland dances, things like that. “This movie,” I told her, “won an Academy Award for its cinematography. There are two amazing facts connected with that. One is that it’s the only Oscar ever awarded on a write-in vote.”

She raised her eyebrows. “You mean it wasn’t nominated?“

“That’s the other amazing fact.”

It is amazing. No disrespect to the three actual nominees that year (Barbary Coast, Les Miserables and The Crusades), but why wasn’t it? Hal Mohr’s cinematography was the one thing about Midsummer on which all commenters on the movie agreed at the time, and they still do now: this is one of the most beautiful black-and-white movies ever shot. Kevin Jack Hagopian of Penn State says Mohr sided with management in a union dispute and the cinematographers’ branch of the Academy refused to nominate him out of pure spite; that makes sense to me. Whatever the cause, a write-in campaign was organized; the Academy allowed write-ins for only two years (1934-35), and this is the only one that ever went the distance.

Mohr had replaced Ernest Haller on the picture when producer Henry Blanke and production chief Hal Wallis found Haller’s footage too murky and dark. Mohr decided it was a case of literally not seeing the forest for the trees, so he ripped out some of the trees designer Anton Grot had erected on the sound stage, had the remaining ones painted and aluminized to be more reflective, and made room for more lighting instruments.

One of Mohr’s instruments is just visible in the corner of this picture; for some reason it wasn’t cropped or retouched out of sight in this version of what became one of the movie’s signature images: fairy queen Titania (Anita Louise) doting on the donkey-headed ass Nick Bottom (James Cagney). This picture was, in fact, my introduction to A Midsummer Night’s Dream in any form, when I came across it at the age of eight or nine, thumbing through a copy of Richard Griffith and Arthur Mayer’s 1956 coffee-table tome The Movies. This picture took up most of page 330; I remember it stopped me cold, and I stared at it a long time. What in the world, I thought, could possibly be the story behind a picture like this?

In time I became more familiar with A Midsummer Night’s Dream; I even directed a production of it during my college years, the only occasion on which I was able, without really trying, to commit an entire Shakespeare play to memory (and no, I can’t still remember it all). So now I know the story of how the glittering, tinselly queen of fairies and the blowhard weaver from working-class Athens come to be tenderly embracing under that tree — she madly in love, he crowned with an ass’s head, each in the grip of a different magic spell.

But my childhood question still stands: What is the story behind that picture — not Bottom and Titania, but A Midsummer Night’s Dream itself? What prompted Warner Bros., home studio of gangsters, fast-talking newsmen and working class stiffs, to take a chance on a highbrow director and a highbrow property, even one in the public domain? Prof. Hagopian says it was Jack Warner’s drive to crash high society, to prove to the upper crust that this son of Russian immigrants had kult-chah. Hmmm. Maybe, but I still wonder, was any amount of boulevard cred worth $1.5 million to this notorious penny-pincher?

Actually, according to historian Scott MacQueen in his commentary to the Midsummer DVD, it was Hal Wallis who prompted Warner to approach Max Reinhardt about committing A Midsummer Night’s Dream to film, and thereby must surely hang a tale. No doubt we could find it in the Warner Bros. archives, with that studio’s penchant for memos and paper trails (“Verbal communication leads to misunderstanding and mistakes. Put your ideas in writing.”), but nobody’s ever bothered to, evidently. There’s no section on Midsummer in Rudy Behlmer’s Inside Warner Bros., barely a sentence in Ted Sennett’s Warner Bros. Presents or in Hollywood Be Thy Name: The Warner Brothers Story by Cass Warner Sperling, Cork Millner and Jack Warner Jr. It’s been decades since I read Jack Warner’s My First Hundred Years in Hollywood, and if he said anything about it, the recollection of it is long gone by now.

Some recounting of this undertaking is overdue, for A Midsummer Night’s Dream is another one of those “miracle pictures” I talked about in my post on Peter Ibbetson. (UPDATE 6/23/20: Since I wrote this in 2010, I’ve learned that my wish had already been granted, by the aforesaid Scott MacQueen, in a long making-of article for the Fall 2009 issue of The Moving Image: The Journal of the Association of Moving Image Archivists. It’s an excellent, eye-opening read, if you can find a copy of it. Try the Project Muse Web site.) Certainly it would have taken nothing less than a miracle for Warners to recoup their massive investment in it. Not that the studio’s publicity department didn’t give it the old college try. Here they’ve leased the whole side of a building in some blighted New York City neighborhood (Probably Brooklyn, Queens, or the Bronx; certainly not Manhattan) to proclaim the picture to anyone happening by the rubbish-strewn empty lot next door. There’s something wistfully gallant about the effort. Likewise the string of special announcement trailers to be found as supplements on the DVD, in which various cast members — Ian Hunter, Olivia de Havilland, Anita Louise, Dick Powell, etc. — step from behind a curtain to avow their pride in being part of Midsummer, all but pleading with the audience to turn out and prove their efforts from December 1934 to the following March had not been in vain.

Unfortunately, they were, as far as Warners’ bottom line for 1935 and ’36 was concerned. Midsummer did okay in the cities and not too bad overseas, but in the small towns it died a thousand deaths. Or three thousand; a record 2,971 theaters exercised their option to cancel their bookings. Jack Warner must have thanked his lucky stars (and the newest and luckiest of all, Errol Flynn) for the unexpected bonanza of Captain Blood.

Max Reinhardt was already an old hand at Shakespeare’s enchanted comedy by the time he strode onto the Warner Bros. lot. It was his favorite play, maybe because it was a 1905 production in Berlin that first made his name and set him on a course to virtually creating the theater-director-as-superstar, as we know the position today. According to his biographer J.L. Styan, Reinhardt had restaged the play over twenty-five times since then, including heralded productions in Oxford, New York and Berkeley.

It was his colossal production in the Hollywood Bowl that piqued Hal Wallis’s interest. For that, Reinhardt removed the famous band shell (what most people think of as the “bowl”; actually, the term refers to the topography of the site) and replaced it with a 25,000-square-foot stage; he had tons of soil trucked in to construct an artificial forest on the hillside behind, including a pond and suspension bridge, to be lined with torch-bearers for the big wedding procession between Acts IV and V.

Oddly enough, for years Reinhardt had been moving in a more minimalist direction for Midsummer; by 1925 he was staging it on a virtually bare stage with only green curtains to suggest the woods outside Athens. But for the Hollywood Bowl, and later for Warner Bros., he returned to the elaborate pageantry that had characterized the play through much of the 19th century.

In the 1940s and ’50s, Laurence Olivier would revolutionize the practice of filming Shakespeare, setting the bar for all who followed. But in 1935 the only bar was imported from the stage. There had been a film inspired by Midsummer in 1909, but that could be no use to anyone now. Reinhardt himself had directed movies in the silent era, but his metier was the stage, and it might have been the undoing of A Midsummer Night’s Dream had his direction carried the day. James Cagney and other members of the cast later recounted how he stalked up and down giving his own rendition of their characters, gesticulating and declaiming wildly (in German) as if he imagined they were still on that huge stage at the Hollywood Bowl projecting to an audience of 15,000 sitting hundreds of yards away. “Somebody ought to tell him,” they whispered.

Not to worry. Reinhardt’s grip of English was shaky, and consequently so was his control of the actors, which fell to William (ne Wilhelm) Dieterle. Dieterle had been a protege of Reinhardt’s in Berlin before becoming a movie director and actor and, in 1931, going over to work in Hollywood, where he flourished. Under contract to Warners in 1934, he was assigned to Midsummer ostensibly as co-director, but actually as a sort of majordomo; he and producer Blanke served as the maestro’s interpreters, and actors and technicians alike remembered the three of them barging into the soundstages where the sets were under construction, growling and barking among themselves in German.

Not to worry. Reinhardt’s grip of English was shaky, and consequently so was his control of the actors, which fell to William (ne Wilhelm) Dieterle. Dieterle had been a protege of Reinhardt’s in Berlin before becoming a movie director and actor and, in 1931, going over to work in Hollywood, where he flourished. Under contract to Warners in 1934, he was assigned to Midsummer ostensibly as co-director, but actually as a sort of majordomo; he and producer Blanke served as the maestro’s interpreters, and actors and technicians alike remembered the three of them barging into the soundstages where the sets were under construction, growling and barking among themselves in German.As things turned out, Dieterle was more the director than Reinhardt once the cameras began rolling; Mickey Rooney, who played Puck, said Dieterle was the only director he ever worked with on the movie (he had also worked for Reinhardt in the Hollywood Bowl). Dieterle bristled at having to play second fiddle to Reinhardt in studio publicity, and he said so to Jack Warner. Warner understood, but explained that — to put it more bluntly than he did — Reinhardt had a name and Dieterle didn’t; the studio’s huge investment had to be protected, and the only way to do it, he figured, was to play up “A Max Reinhardt Production” to the max (pun intended).

In the final analysis, the dual director credit was probably just; let’s give Reinhardt credit for conception and Dieterle for execution, each taking the lead where the other was less at home. In Part 2, I’ll talk a little more about both facets — conception and execution — of the final product.

When I mentioned to a friend that I was planning a

post on William Wyler (which has now turned into

several), he said, “Good. I’ll be interested to see

what you consider his…” — he searched for the

right word — “…apotheosis.”

To tell the truth, at that point I hadn’t given much

thought to apotheosizing the man, though I guess

that’s what I’ve done. The dictionary gives two

definitions of apotheosis: (1) the elevation of

someone to the status of a god; and (2) the epitome

or quintessence. So since my friend brought it up,

what is, or was, the apotheosis of William Wyler?

Now that I’ve elevated him to somewhere in the

vicinity of godhood, what should we consider the

epitome and quintessence of his work?

To answer that, we might as well start by taking a look at Wyler’s three Oscar-winning best pictures. Ben-Hur is the easiest to dismiss; in fact, it’s the hardest one not to. Check out this poster from 1959: The Entertainment Experience of a Lifetime. At the time, despite the exclamation point, that seemed a simple statement of fact, and it’s hard at this remove to explain the impact of Ben-Hur to anyone who wasn’t there. Star Wars wasn’t a patch on it, though the mystique has outlasted Ben-Hur‘s. Star Wars was the movie of the year in 1977, the way Titanic was in 1997. But in 1959 and ’60, Ben-Hur was a movie for all time; the few dissenting voices were swamped in the ballyhoo.

Check out Wyler’s billing on the poster, too — bigger than anything but the title. Certainly bigger than author Lew Wallace way up there in the fine print, but bigger too than even the stars or producer Sam Zimbalist (whom the stress of the project sent to an early grave). There’s an apotheosis for you.

By the time the Oscars rolled around Ben-Hur was a juggernaut that would not be denied. It seemed a waste of time even to bother finding four other nominees; the thankless mantle of designated also-ran was eventually conferred on Anatomy of a Murder, The Diary of Anne Frank, The Nun’s Story and Room at the Top. Nobody would have blamed those hapless producers if they had just stayed home on award night, so foregone was the conclusion. But what a change a half-century makes; all four of the sacrificial nominees have aged more gracefully than the winner. For that matter, the silent 1925 Ben-Hur holds up better, especially now on video, with its proper running speed and Technicolor sequences restored and spruced up with a stirring Carl Davis score; only the 1959 chariot race surpasses the original (even that, not by much), and Wyler had to leave the race to second-unit men Andrew Marton and Yakima Canutt.

Mrs. Miniver was also a juggernaut in 1942, but that time the momentum was fueled by patriotism instead of studio hype. In this poster the exclamation point is appended to the claim “Voted the Greatest Movie Ever Made.” Whose votes were counted is left obscure, but there’s no denying that Miniver was beloved in its day, and its Oscar was similarly assured.

The picture began as unabashed pro-British propaganda in their war against Germany; it changed to pro-Allied propaganda when Pearl Harbor was attacked midway through production. Its morale value was a real boon to the war effort, and it deserves points for fervent sincerity, but alas, it’s a museum piece today, with the same Hollywooden imitation-Englishness that besets MGM’s 1938 A Christmas Carol. (In Miniver‘s case, British audiences seemed not to mind, no doubt taking the intention for the deed.) Among its fellow best picture nominees, even the rampant flag-waving of Wake Island, The Pied Piper and Yankee Doodle Dandy wears better today. Add in The Invaders, Kings Row, The Pride of the Yankees, The Talk of the Town and The Magnificent Ambersons — and the case for Mrs. Miniver grows weaker with each title. Potent blow for righteousness that it was in its day, Miniver no longer has the ring of truth it had in 1942.

I use that phrase deliberately, because it brings to mind the first time I saw The Best Years of Our Lives, in the early ’70s when Sam Goldwyn had finally released at least some of his films to television. I watched Best Years one night with a friend, a conscientious objector then in the midst of the Vietnam War. As we watched the movie unfold, Wyler’s (and writers MacKinlay Kantor and Robert Sherwood’s, and producer Sam Goldwyn’s) story of three World War II vets struggling to readjust to civilian life, my pacifist-conscientious-objector-draft-dodger pal turned to me and said, “This still has the ring of truth, doesn’t it?”

It was true when he said it at the height of Vietnam, and it would still be true if he said it again today. Of Wyler’s three best pictures, The Best Years of Our Lives is the one that holds up with the fewest allowances made. True, it’s overshadowed today by another 1946 picture, one it beat in nearly every Oscar category: Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life. Well, I suppose that’s natural; Christmas comes back again every year and World War II only ended once. If the voting for best picture of ’46 got a do-over, Wonderful Life might well take the prize (I’d probably vote for it myself). Olivier’s Henry V would certainly be a strong candidate. Even The Razor’s Edge and The Yearling might have their cheering sections.

Still, none of this negates the award having gone to Best Years. Wyler’s movie is one of those rare ones that tackled a current issue foremost in the minds of nearly everyone who saw it, dealt with the issue head-on and unflinching, and had (yes) the ring of truth to the very audience least likely to tolerate any Hollywood phoniness about it. Not only in America, and not only among the Allies. The movie was a smash hit from Stockholm to Sydney, winning best picture awards (Jan Herman tells us) “from Tokyo to Paris.” When we look at the Oscars for 1946, we don’t have to scratch our heads and wonder what people were thinking back then; The Best Years of Our Lives tells us.

So much for those three. But it’s a truism that people seldom win Oscars for their best work, and nobody illustrates the point better than William Wyler. To find his best work — his (ahem) apotheosis — I do think you have to look further than even the best of those.

High on my short list — and right at the top, probably — would be the two pictures Wyler made on loan to Warner Bros. with Bette Davis. I’ve told the story of Jezebel and the 48 takes with the riding crop. Later on that same picture, when executive producer Hal Wallis made noises about firing Wyler for (what else?) wasting film and ordering too many takes, Davis went to bat for her director and saved his job, offering to work overtime if it would help (and only if they’d keep Wyler on).

True, she was having an affair with Wyler at the time, but she was a hard-nosed career woman who (if you’ll pardon the expression) never let the little head do the thinking for the big head. Whatever was going on during off-hours, she knew he was getting the performance of her life (so far) out of her, and was doing almost as much for others in the cast — George Brent and (of all people) Richard Cromwell were seldom as good, and never better.

He did almost as much on The Letter in 1940, two years later, and with a much better script (from the story by W. Somerset Maugham). Davis didn’t get the Oscar for this one, but she’s nearly as good as she was in Jezebel, showing the feral fang-and-claw passions roiling under a studied veneer of respectability. (The Wyler-Davis magic failed only on their third and final movie together, 1941’s The Little Foxes, and then only because the headstrong Davis wouldn’t listen to him. He wanted a more textured performance, but she insisted on going deep into Wicked Witch territory. Her two-dimensional approach wasn’t enough to sink the movie — Davis was always worth watching, no matter what — but it did allow the all-but-unthinkable: not one but two other performers, Charles Dingle and Patricia Collinge, stole the picture from her.)

Other pictures should make the list. Wuthering Heights, no doubt, and These Three and Dodsworth. Hell’s Heroes, despite its early-sound primitivism — or maybe because of it — was a real eye-opener for me, showing a grittier, closer-to-the-bone Wyler than I’d ever seen. And Roman Holiday is a delight from beginning to end; all those heavy-prestige years with Sam Goldwyn, followed by weighty dramas like The Heiress and Detective Story, hadn’t sapped Wyler’s sense of fun, nor his ability to whip up a scrumptious feather-light souffle even in the broiling heat of an Italian summer. The famous Mouth of Truth scene, improvised by Wyler and Gregory Peck on the spot and sprung on an unsuspecting Audrey Hepburn, is a little gem of wicked fun, one of the great moments in Wyler’s career — and Peck’s, for that matter, and Hepburn’s. For that and other reasons, Roman Holiday makes my short list too.

Maybe not on the short list but deserving to be remembered (at least more than it seems to have been since it was the hot one to see back in 1965) is The Collector, essentially a two-characters-on-one-set drama of a timid kidnapper and his beautiful captive in which Wyler got brilliant performances from Terence Stamp and Samantha Eggar. Coming after the turgid Ben-Hur and the miscarried The Children’s Hour, here was reason to believe Wyler hadn’t lost it, and it gained him his final Oscar nomination. But maybe “it,” whatever it was, was slipping through his fingers at that; Wyler’s hearing and his lungs were deteriorating, and some of the excitement had surely gone out of the game. His next picture, Funny Girl, was a hit, but it strikes me as basically Ben-Hur with songs, and Barbra Streisand instead of a chariot race to provide excitement (and Wyler’s final acting Oscar). His next and last, The Liberation of L.B. Jones, was a physical ordeal, and critically savaged, barely released, hardly seen. He was proud of the picture, but he knew the grind would kill him if he tried to keep it up, so he got out, having nothing more to prove.

I guess my friend’s curiosity will have to remain unsatisfied, at least by me. I can’t name a single “apotheosis,” and even now I’ve probably left somebody’s favorite out. There’s no single “elevation” for me; there are just too many peaks, like the Himalayas with a dozen Everests.

Joel McCrea’s little ploy turned out to be a pretty momentous backfire. In 1935 he was under contract to Samuel Goldwyn, the irascible producer who had gone independent, largely because no other mogul in the picture business could stand to work with him.

McCrea knew that the boss was looking for an actress to add to his small stable of stars — a Bette Davis, a Katharine Hepburn, somebody with “that little something extra” — and McCrea thought he had just the woman for him: his wife, Frances Dee. She had already appeard in over thirty pictures, including RKO’s Little Women (playing Meg) and Of Human Bondage, and McCrea had been pitching her to Goldwyn for months without success. Now he took the bull by the horns: he showed up at the studio with a print of Dee’s latest picture for Fox, a Cinderella story called The Gay Deception, and screened it for Goldwyn.

Goldwyn loved the picture, but for the wrong reason as far as McCrea was concerned; when the lights came up, he was no more interested in Frances Dee than he had been the day before. Instead, he turned to McCrea. “Who directed this?”

“A funny little guy named Wyler.”

What was it about The Gay Deception — a frothy comedy about a small-town secretary who uses a $5,000 sweepstakes prize to pose as an heiress at the Waldorf, where she meets a prince incognito as a bellboy — that convinced Goldwyn he’d found the director he was looking for? Jan Herman doesn’t say in A Talent for Trouble, nor does A. Scott Berg in his magisterial Goldwyn — and Berg had unrestricted access to Goldwyn’s archives, so maybe Goldwyn never said either. That kind of question is just what makes Sam Goldwyn such an enigma. How do we figure this guy out?

If Goldwyn was nothing more than a crass and ill-tempered parvenu who threw money around in an effort to buy a reputation as a class act, all the time raging and bullying and mangling the English language, how do we explain this mind-boggling flash of insight that changed his life, and Wyler’s — and left no small ripple in Hollywood history? For whatever reason, he decided the director of this lighthearted romantic comedy was just the man he wanted to direct a searing drama about two schoolteachers accused of lesbianism.

When the two men met later that summer of 1935, Wyler said Goldwyn “couldn’t have been more charming, but I thought he’d lost his mind. He wanted to film The Children’s Hour.” Lillian Hellman’s play was a scandalous success on Broadway, and the Hays Office had tried to warn Goldwyn off bringing it to the screen. But Hellman maintained that the play was about the power of a lie, not lesbianism; Goldwyn was going to give her the chance to prove it by hiring her to write the screenplay, and he wanted Wyler at the helm.

The result was These Three; the Hays Office allowed Goldwyn to proceed only if he removed any suggestion of “sex perversion” and didn’t make any reference to Hellman’s original title on screen or in any of the picture’s publicity. Hellman proved her point by changing the schoolgirl’s lie to a more conventional accusation of illicit heterosexuality. And Wyler proved it again 26 years later, by default: he remade the movie under its original title and — the Production Code having loosened up in the meantime — with its original lesbian theme intact. That time, Hellman wasn’t available to do the script, and she hated the final film. Wyler himself wished he had never made The Children’s Hour.

Not so These Three, which even in 1962 outshone its remake, and in 1936 was exactly the succes d’estime Goldwyn was looking for, and a box-office hit to boot. Their next picture together, Dodsworth, from Sinclair Lewis’s novel and Sidney Howard’s play, brought Goldwyn within striking distance of his Holy Grail: the Academy Award for best picture. It was nominated for that and six others (including Wyler for best director), although only Richard Day’s art direction won. But Goldwyn had found the director who could give him the prestige pictures he wanted sent out under his name. Wyler, for his part, found a producer entirely unlike Junior Laemmle back at Universal, one willing to spend the money to support the style that in time would dub him “90-Take Wyler.”

It was a professional marriage made in heaven — with plenty of hell along the way. There was a reason Goldwyn was called Hollywood’s lone wolf: he fought with everybody — with Edgar Selwyn, his first partner in movies; with United Artists, the distributor of his pictures; with A.H. Giannini, UA’s banker; with his stars, directors, lawyers. Everybody.

He fought with Wyler, too. By the time of their last picture together, The Best Years of Our Lives in 1946, he spoke of having “occasional attacks of ‘Goldwynitis.'” After one run-in with Goldwyn he came late to the set, fuming: “This goddamned picture! Goldwyn wants it Produced by Sam Goldwyn. Directed by Sam Goldwyn. Acted by Sam Goldwyn. Written by Sam Goldwyn. Seen by Sam Goldwyn.”

For his part, Goldwyn complained that Wyler shot as if he owned stock in a film company. Part of the reason for all this is the fact that they were so much alike. They were both inarticulate, though each handled it in different ways. Goldwyn blustered and railed, shaking his fist at the top of his voice. Wyler didn’t; he just quietly ordered another take, saying little. Neither man could tell people exactly what he wanted, but each knew it when he finally saw it. In Goldwyn A. Scott Berg quotes Ben Hecht on the producer:

Ben Hecht wrote that Goldwyn as a collaborator was inarticulate but stimulating, that he “filled the room with wonderful panic and beat at your mind like a man in front of a slot machine, shaking it for a jackpot.”

“Inarticulate but stimulating” describes Wyler as well as it does Goldwyn. If Goldwyn filled a room with wonderful panic, Wyler filled it with equally wonderful desperation. Staying with Hecht’s metaphor, if Goldwyn shook that slot machine for a jackpot, Wyler stood there dropping coin after coin into it, figuring that sooner or later the lemons and cherries and bananas would line up the way he liked them. And during the years from 1936 to 1946, when Wyler made the pictures that would secure his reputation as a man who couldn’t make a flop, most of the coins he used belonged to Sam Goldwyn.

One of Wyler’s jackpots, and Goldwyn’s, was also Hecht’s — his and Charles MacArthur’s. The two had written an adaption of Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights while on vacation in 1936, just on spec. They sold it to Walter Wanger for Wanger’s star Sylvia Sidney. But those two got into a screaming match over another picture, and when Wanger grumbled that the script needed “laughs,” the writers asked Goldwyn to buy the property from him.

Goldwyn wasn’t interested; the atmosphere was too grim and the flashback structure confused him. But when Wyler — stretching the truth a bit — told him Jack Warner was considering buying Wuthering Heights for Bette Davis, Goldwyn couldn’t resist the idea of stealing it out from under him. By the time the picture premiered in April 1939, the movie Goldwyn hadn’t been all that interested in making had been transformed in his mind into the one he thought he’d be remembered for (although he never did get the title right; he always called it “Withering Heights”). He’d been practically conned into making the picture, but whenever anyone mentioned “William Wyler’s Wuthering Heights,” he’d correct them: “I made Withering Heights. Wyler only directed it.”

“Only.” That’s how petty Goldwyn could be; he was willing to pay to get the best, but he never shrank from grabbing credit for how things turned out. But as Wyler rhetorically asked an interviewer in 1980: “Tell me, which pictures have ‘the Goldwyn touch’ that I didn’t direct?”

Well, there was The Pride of the Yankees (Sam Wood did that one), and Ball of Fire (Howard Hawks), and The Hurricane (John Ford). But Wyler’s point is well-taken. No other director worked as many times for Goldwyn — seven — and of the seven times Goldwyn was in the running for a best picture Oscar, only two were directed by anyone else (Yankees and The Bishop’s Wife). Without movies like These Three, Dodsworth, Wuthering Heights, Dead End and The Little Foxes, the vaunted “Goldwyn touch” could well boil down to those Eddie Cantor musicals, Danny Kaye’s 1940s comedies, and Guys and Dolls.

Take this picture, for example. If there’s one movie besides Wuthering Heights for which Goldwyn is remembered now, it’s The Best Years of Our Lives. It’s the movie that finally got Goldwyn into the winner’s circle on Oscar night, and it was Wyler’s picture one hundred percent.

Goldwyn tried to talk him out of making it. Goldwyn had commissioned the story from writer MacKinlay Kantor as World War II was finally inching to its end; he said he wanted something about returning soldiers, and he gave Kantor carte blanche as to the story; but when Kantor came out with Glory for Me, a 288-page novel in blank verse, Goldwyn lost interest and wrote the investment off as money down the hole.

In October 1945 William Wyler was himself a veteran back from the war, and he connected with Glory for Me as Goldwyn never could. He still owed Goldwyn one more picture under the contract that had been in abeyance for the duration, and this was the one he wanted to make. Goldwyn demurred. Wyler insisted. He got his way, and he and Goldwyn (among others) got their Oscars.

But service in World War II taught William Wyler one lesson that didn’t make its way into The Best Years of Our Lives: he learned that life is too short to deal with people like Samuel Goldwyn. When Goldwyn denied him the “A William Wyler Production” credit he’d promised, snubbed him at the after-Oscar party, then turned out to have cooked the books to shortchange him on his profit participation, Wyler washed his hands.

Wyler could have said, “I made The Best Years of Our Lives. Sam Goldwyn only produced it.” But he never did, because William Wyler was a gentleman. With all he and Goldwyn had in common, and after all they had helped each other to accomplish, that was the one big difference between them.

.

Thalberg called him “Worthless Willy.” This surely makes William Wyler the only recipient of the Academy’s Irving G. Thalberg Award to have been publicly disparaged by the man the award was named for.

Thalberg did have his reasons. Only three years older than Wyler, he was far beyond him in stature at Universal when Wyler started there as an errand boy in 1921. According to Wyler’s biographer Jan Herman, the only time Universal’s youthful production chief deigned to notice the 19-year-old Wyler, it didn’t go well for the future director. “You read German, don’t you?” Wyler, fairly fresh from Europe and still honing the command of English he’d begun developing there, said he did. Thalberg handed him a German novel, a property the studio was considering buying for director Erich von Stroheim. “Bring me a synopsis in English on Monday.”

This was on Friday, and Wyler didn’t make the deadline; he didn’t even finish the book. Monday came, then Tuesday and Wednesday before he could even tell Thalberg what the book was about; he appears never to have done a written synopsis. It also appears that Thalberg was administering a test — and Wyler flunked. In any case, Wyler — young and unfocused — never got another personal assignment, however trivial, from Thalberg. The “Worthless” moniker came along later, when Thalberg got wind of the teenager’s arrests for reckless driving; Thalberg must have decided the kid would never amount to much.

If so, then Thalberg, who died at 37, lived just long enough to get an inkling of how wrong he was. Even by the time Thalberg left Universal in 1924 for the new-minted super-studio MGM, Worthless Willy had already amounted to an assistant director — of sorts. On The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), Thalberg’s pet project at Universal, Wyler was still just an errand boy, but now he was running errands for assistant directors Jack Sullivan and Jimmy Dugan, wrangling the picture’s thousands of extras and getting his first chance to wield the coveted megaphone.

The anecdote of the German novel is a telling one. He may have been a slow starter at Universal, and may have struck higher-ups — and in those days nearly everybody at Universal was higher up than he was — as a bad bet, but he was already showing a trait that would follow him all through his career: Willy Wyler didn’t like to be hurried. In time, the “Worthless Willy” nickname would give way to another: “90-Take Wyler.”

Bette Davis told a story about working with Wyler on Jezebel in the fall of 1937. Her first scene called for her to stride into her plantation home after dismounting from her horse and saucily slinging the long train of her riding outfit over her shoulder on her riding crop. At Wyler’s request, Davis had practiced long with the crop and felt ready to nail the scene in one take. In fact, she thought she did, but Wyler disagreed. He ordered another take, and another, and another. After a dozen takes, Davis, who had rarely required more than two takes in her entire career so far, was exasperated. “What do you want me to do differently?”

“I’ll know it when I see it.”

Whatever it was, Wyler saw it on the forty-eighth take. “Okay, that’s fine.” And he called a wrap for the day.

Davis was furious, and demanded to see the rushes of the day’s work. Wyler obliged. Davis no doubt was primed to fly into a self-righteous tirade: “What was wrong with that take…or that one…or that one?” But she never did. She walked into the screening room believing that she’d done the action exactly the same every single time, but now she saw that she hadn’t. Each take was different, and the forty-eighth was the best.

That’s how 90-Take Wyler operated, and in a way it wasn’t all that different from Worthless Willy. He knew what he wanted, but he wasn’t one of those directors — not always, anyway — who could get it from an actor with a few well-placed words. There’s a famous story about how Wyler’s friend John Huston, directing The African Queen, saved Katharine Hepburn from playing her character as a sour, prissy old-maid missionary (and probably saved the whole picture) by a simple, seemingly offhand remark comparing the character to Eleanor Roosevelt. Wyler didn’t work that way. There are countless stories of Wyler ordering another take, saying things like “It stinks.” “Do it again. Better.”

Charlton Heston on Ben-Hur, for example. One night, he said, Wyler came to him in his dressing room. “Chuck, you gotta be better in this picture.”

Nonplussed, Heston said, “Okay. What can I do?”

“I don’t know. I wish I did. If I knew, I’d tell you, and you’d do it, and that would be fine. But I don’t know.”

“That was very tough,” Heston recalled. “I spent a long time with a glass of scotch in my hand after that.”

Wyler, it seems, didn’t always issue instructions like a recipe to his actors. But he knew what he wanted. And he knew that “I’ll know it when I see it.”

These anecdotes conjure an image of a director passively waiting for lightning to strike, and willing to spend any amount of time and his producer’s money while he waited. What they don’t suggest is the process his refusal to accept the merely adequate sparked in his actors and writers. On their first picture together, The Big Country, Heston took exception to some minor piece of Wyler’s direction and wanted to discuss it. He didn’t have his script handy, so he asked to borrow Wyler’s.

Wyler always carried his script in a leather binder, with the titles of his movies engraved in gold inside the front cover; when he finished a picture, he’d take the script out, engrave that one’s title on the cover and move on to the next. As Heston took Wyler’s script, it flipped open to the inside cover and he saw the titles engraved there: Dodsworth, Dead End, Jezebel, Wuthering Heights, The Letter, The Westerner, The Little Foxes, Mrs. Miniver, The Best Years of Our Lives, The Heiress, Detective Story, Roman Holiday…

As Heston stared, Wyler grew impatient. “What is it, Chuck? What’s on your mind?”

Heston closed the script and handed it back. “Never mind, Willy. It’s not important.”

Wyler began directing on two- and five-reel westerns at Universal, where they didn’t want it good, they wanted it Thursday afternoon. The formulas were simple and unsubtle, and the movies had to move. Wyler showed, in now-forgotten titles like Ridin’ for Love, Gun Justice and Straight Shootin’, that he could turn it in Thursday afternoon and good. As the importance of his assignments increased, he drew on his bosses’ memory of how right he had gotten things before — under the gun, with the front office relentlessly beancounting — to take more time and money to get it exactly right this time. And as his reputation grew (and stayed with him nearly to the end) as a man who couldn’t make a flop, the people who worked with him tended more and more to take his word, like Heston on The Big Country and Ben-Hur. If Willy thinks I can do better, he must be right, and it’s up to me to figure out how.

When a director insists on take after take, saying nothing but “again” and “it stinks,” an actor’s response is usually to think (or say), “This guy’s giving me nothing, and he’s a tyrant to boot.” And some did. Jean Simmons worked for Wyler on The Big Country (1958), and even thirty years later she declined to discuss the experience with Jan Herman. Not so Sylvia Sidney, who dripped venom talking about doing Dead End fifty years after the fact. Ruth Chatterton didn’t wait that long; she was every inch the affronted diva on Dodsworth even as Wyler and producer Sam Goldwyn were trying to jumpstart her fading career (“Would you like me to leave the studio, Miss Chatterton?” “I would indeed, but unfortunately I’m afraid it can’t be arranged.”).

Whatever the truth of these situations, the point is what conspicuous exceptions Simmons, Sidney and Chatterton are among the legions of actors who worked with Wyler. The tales of his calling take after take are recounted with affection, not exasperation — not only by the Oscar winners, and not only years after wounded feelings have healed (Bette Davis got over her snit instantly). Wyler apparently never uttered the words “I know what I’m doing; trust me,” but that seems to be the effect he had on people. Combined with a powerful personal charm, he exuded an atmosphere of serene confidence on the set that made people want to please him, even as they struggled through twenty, thirty takes or more trying to figure out what the hell he wanted them to do. Wyler’s attitude was that they could do better; their response was to work all the harder to prove him right.

This is the intangible ingredient in Wyler’s pictures, along with the ones we can identify and point to: the bravura or simply spot-on-genuine performances, the incisive writing, the striking cinematography (Wyler worked seven times with the great Gregg Toland, and they brought out the best in each other), the handsome production designs. If you want to find the “personal element” in Wyler’s pictures, there it is: He had the confidence to take his time. In remarkably short order, thanks to luck as well as talent, he established a track record that allowed him to insist on it.

Gregory Peck nailed it exactly: “He was not one to talk a thing to death…What worked worked, and he knew how to recognize it…[N]ot all directors know how to do that. They pick the wrong take, or they’re not open to what can happen on the spur of the moment. Willy had a special sensitivity to that. He sensed the interplay between actors…This was ‘the Wyler touch.’ It’s why so many actors won Oscars with Willy, because he recognized the moments that brought them alive on the screen.”

I haven’t even gotten around to talking about Sam Goldwyn, have I? Next time, then; that testy, fruitful relationship deserves a post all to itself.

When William Wyler died in 1981, writer-director Philip Dunne delivered a euolgy at a memorial service in a packed auditorium at the Directors Guild of America. “Talent,” he said, “doesn’t care whom it happens to. Sometimes it happens to rather dreadful people. In Willy’s case, it happened to the best of us.”

Everybody called him Willy. Naturally enough — it was his name. He was born Willi Wyler, actually, in Alsace on July 1, 1902. When he began directing two-reel westerns for Universal in 1925, they Anglicized — and, to their minds, dignified — his given name to William, and he went along, but he never changed it legally, and to his friends and family he was Willy to the end.

He looks more like a Willy here, on the left holding the megaphone, playing a Hitchcockian cameo as the assisstant director of the film-within-the-film in Daze of the West, his last two-reeler for Universal; he had already begun directing five-reel westerns and would soon graduate to more prestigious (for Universal, anyhow) features. He’s 25 in this picture and has already been directing for two years, the youngest on the Universal lot and probably the youngest in Hollywood. (A few years later, he took mild umbrage at seeing Mervyn LeRoy over at Warners touted as Hollywood’s youngest — “He had press agents and I didn’t.” — even though LeRoy was two years older and began directing two years later. Much later on, coincidentally, both would work for producer Sam Zimbalist on the two huge Roman epics that bookended the 1950s at MGM: LeRoy on Quo Vadis and Wyler on Ben-Hur.)

In between the one-week shoot on Daze of the West and the eight months on Ben-Hur, Wyler had one helluva run. In the end it may have been Ben-Hur that proved the undoing of his reputation, at least among “serious” film students. Wyler certainly thought so: “Cahiers du Cinema never forgave me for the picture. I was completely written off as a serious director by the avant-garde, which had considered me a favorite for years. I had prostituted myself.”

Well, it certainly didn’t seem that way at the time. At least among the hoi polloi and mainstream movie reviewers, Ben-Hur looked like Wyler’s masterpiece; his Oscar for directing it was only one of the eleven it won, a record that stood for 37 years. In 1959 and ’60, Ben-Hur wasn’t simply a great movie, it was a touchstone in the march of human culture. It was everywhere; you couldn’t catch a cold without blowing your nose on Ben-Hur kleenex, and everybody who even wanted to be anybody simply had to see it.

In time cooler heads prevailed, and it became clear that as great movies and cultural touchstones go, Ben-Hur was neither. But by then the damage was done; the avant-garde (whoever they are) had abandoned Wyler for — oh, pick a name: Howard Hawks? Vincente Minnelli? John Cassavetes, Nicholas Ray, Samuel Fuller? Andrew Sarris’s American Cinema relegated Wyler to four tiers below the Pantheon, in a section headed “Less Than Meets the Eye.” David Thomson’s Biographical Dictionary of Film dismissed him as “Hollywood’s idea of an outstanding director.”