Discs 2 and 3 of Classic Musical Shorts from the Dream Factory are practically all Technicolor, except for one short, What Price Jazz with Ted Fio Rito and his orchestra, which credits Technicolor but evidently survives only in black and white. The Warner Archive emphasizes the color in these MGM shorts, and it’s a little misleading (like those video compilations from The Ed Sullivan Show that give you the impression the only guests Sullivan ever had were the Beatles, Aretha Franklin and the Rolling Stones). Still, while it’s true that Metro came late to the Technicolor party where features were concerned (their first was 1939’s Sweethearts; only Columbia and Universal waited longer to jump on the bandwagon), the studio dabbled extensively in Technicolor shorts throughout the ’30s.

There were, for one thing, the ubiquitous James A. FitzPatrick Traveltalks (“As our boat pulls away from the shore and the sun sinks slowly in the west, we bid a reluctant farewell…”) — a fertile field for another Warner Archive collection. And the color shorts collected here — some, like Crazy House and The Devil’s Cabaret, composed of remnants of MGM’s aborted feature The March of Time (see Richard Barrios’s A Song in the Dark for a detailed retelling of that fiasco), while others were little mini-musicals created from scratch.

See, for example, the two-color Tech Over the Counter, in which a hustling young go-getter turns his father’s stodgy department store into a sort of daylight nightclub. (The picture here is of young Betty Grable, only 15 but already playing a married woman shopping for a baby. As you can see, it would take the coming of 3-strip Technicolor, and a little more maturity on her part, to do full justice to Betty’s looks.)

A few of the shorts stretch the meaning of “musical” in the title of the collection. The Spectacle Maker (1934), for one, is a fairy tale parable about a maker of magic lenses; one makes people see only beauty, which makes him famous and beloved, while another makes them see only the truth, which gets him condemned for witchcraft (don’t worry, all comes out well). Music is limited to some maypole dances and a simple ditty sung by little Cora Sue Collins as a princess.

The Spectacle Maker is noteworthy for two things besides the pretty color: (1) It was the first directorial effort of Australian transplant John Villiers Farrow, who would go on to marry Maureen O’Sullivan, direct such movies as Five Came Back, Wake Island, The Big Clock, Alias Nick Beal and Hondo, and father an actress daughter named Mia; and (2) the title role was played by Christian Rub, who would gain immortality as the voice and physical model for Gepetto in Walt Disney’s Pinocchio (his appearance in this short may in fact have gotten him the job).

My favorite shorts in the whole collection are the color series produced by Louis Lewyn, invariably boasting “A Galaxy of Screen Stars” or words to that effect. My uncle (a film buff like me) says, “I always find these shorts interesting, though not necessarily good,” and that pretty much nails it. Lewyn’s modus operandi was to shoot these little 1930s showcases at the favorite playgrounds of the stars: the Cocoanut Grove nightclub and Lido Plunge spa (“Feminine Conditioning”) at L.A.’s Ambassador Hotel, or at Santa Barbara, Catalina Island, Palm Springs, etc. Then, I’m guessing, he would find stars who were between assignments and offer to put them up for a few days during shooting, in return for which they would do a little turn in front of the camera, or even just sit at a table and wave on cue. In this way, Lewyn would get a star-studded short in vivid (even garish) color, and his audience would get what seemed like a privileged glimpse of their screen idols at play.

In the first of these, 1934’s Star Night at the Cocoanut Grove, emcee Leo Carillo (for once blessedly free of his “Ohhhh, Ceesco” accent) recites Don Blanding’s poem “Hollywood”:

“Bunk, junk and genius, amazingly blended…

Shoddy and cheap — and astonishingly splendid.”

I love that line “Bunk, junk and genius;” in fact, I briefly considered making it the name of this blog, before deciding to go with something more descriptive and less obscure.

We have Lewyn’s come-and-put-in-an-appearance approach to thank for our only Technicolor look at the legendary Mary Pickford; gone but not forgotten by 1934, she steps to the mike, graciously addresses her public, and flirts with a youthful Bing Crosby before returning to her ringside table to beam at the Cocoanut Grove’s floor show.

Pickford wasn’t the only silent-era veteran who made an appearance for Lewyn. Chester Conklin, Ben Turpin, Hank Mann, Buster Keaton, William S. Hart and Rex Bell all show up in one locale or another; here’s a look at Turpin cavorting with a trio of comediennes at the Lido. Not all of these old-timers were as well-fixed and retired-by-choice as Mary Pickford. I think it speaks well of Lewyn that he was willing to give them a day or two of work and help them stay in the public eye, maybe pick up a few bucks to boot. (And while I’m thinking of it, isn’t it a pity that Rex Bell’s wife Clara Bow couldn’t have appeared with her husband, smiling and waving at the fans; wouldn’t it have been a treat to see her blazing red hair in 3-strip Technicolor?)

It wasn’t all idle stars and silent vets in a Lewyn short. He showcased the occasional new face as well. Here’s one from a Cocoanut Grove fashion parade of Travis Banton’s Egyptian-themed gowns; do you recognize her? I didn’t before she was pointed out to me, and her name isn’t mentioned as she sashays down the steps with the other models. But that’s 19-year-old Clara Lou Sheridan, before she permanently changed her first name to Ann.

Or how about this, from La Fiesta de Santa Barbara (’35, directed by Lewyn, produced by Pete Smith). Can you name that blonde cowgirl between Toby Wing and Chester Conklin? Believe it or not, underneath that thick layer of Technicolor makeup is Ida Lupino, still five years from They Drive by Night and a helluva long way from High Sierra and Road House.

Toby and Ida in their colorful western duds offer a hint to another surefire ingredient in Louis Lewyn’s short subjects: beautiful women and plenty of them. Whether they were lining up for volleyball on the Lido’s trucked-in sands…

…heralding a comic Andy Devine bullfight in Santa Barbara…

…clustering at the feet of comic Fuzzy Knight in Palm Springs…

…yo-ho-ho-ing with the Halloween pirates on Catalina Island…

…or parading in faux Chinese feathers in an even faux-er Chinese tea garden….

…Lewyn made sure that they were never far from the camera for long. Lewyn (and his frequent director Roy Rowland) seem to have believed that those gorgeous Technicolor flesh tones looked better and better the more flesh you used to show them off.

And tell the truth — can you disagree?

Looking at these short peeks into Hollywood recreation, brightly painted for the Technicolor camera and carefully scrubbed into good clean fun for home consumption, I can’t help wondering what the stars were thinking as they sat and smiled and nodded and waved at their “host” (Leo Carillo, Reginald Denny, Elissa Landi, Chester Morris, Lee Tracy, whomever), whose joshing introductions were no doubt shot at an entirely different time, maybe even on a different day. And what did movie colony insiders think when they saw the finished product at some real Hollywood party?

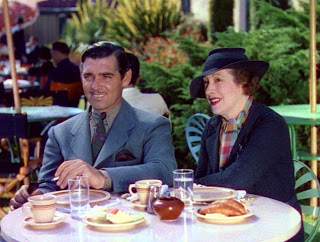

Did this shot of Cary Grant and Randolph Scott on Catalina draw knowing glances from their peers and co-workers the way it does from the gleeful gossips of today? There doesn’t seem to be any such winking over a similar shot of Gary Cooper and Richard Cromwell at the Cocoanut Grove. And how much less over another shot of Sir Guy Standing sharing a table with a twinkling Toby Wing (what did they find to talk about?).

Surely this shot of Mr. and Mrs. Clark Gable on the lawn at the Lido must have startled at least some viewers in St. Louis or Des Moines — is that his aunt? Host Reg Denny is quick to point out that the lady is in fact his wife, making her (at least by marriage) the Queen of Hollywood. But in 1935, when this shot was taken, not even Gable could have known how uneasy sat his consort’s crown. It is for us, three-quarters-of-a-century on, to savor the poignant knowledge that this nice, motherly-looking lady is about to go toe-to-toe with Carole Lombard — and lose, big-time. Do we even remember her name? (Maria “Ria” Langham.)

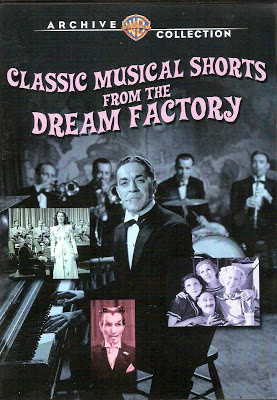

After the gaudy splash of Discs 2 and 3, and Louis Lewyn’s relentlessly hearty civic-booster showmanship, Disc 4 in the collection can’t help looking a little anticlimactic, even drab. We’re back to black and white, even for Lewyn’s peppy Billy Rose’s Casa Manana Revue and Sunday Night at the Trocadero, and the collection rounds out with a sampling of Musical Merry-Go-Round shorts from 1948 with disc jockey Martin Block, creator of radio’s Make Believe Ballroom. As the picture here suggests, the shorts are essentially Block sitting at his microphone playing records and interviewing guests, with interpolated shots of the bands in question to save us from merely watching the turntable spin. (The pic also, I think, hints at the dissatisfaction with L.A. that would send Block scurrying back to New York as soon as his KFWB contract was up.)

From canned vaudeville to illustrated radio in twenty short years — that’s the arc of the theatrical movie short as presented in Classic Musical Shorts from the Dream Factory. The first Oscars for short subjects were awarded in 1931-32, and in retrospect we can see that their golden age wasn’t long. By ’48, even at lofty MGM, things had devolved to a deejay and his record collection; television and the antitrust breakup of the Hollywood monopoly were just around the bend to deliver the death blow to the short-spangled movie program. Warner Bros.’ Joe McDoakes would morph into TV’s George Jetson, and Pete Smith would wind up doing charcoal commercials.

The death spiral wasn’t quick; it was almost as long as the the golden age itself. Walt Disney would long depend on animated shorts and his groundbreaking True Life Adventure and People and Places documentaries to fill out programs with his animated and live-action features, and Looney Tunes would limp into the 1960s, growing cheaper and more lackluster almost by the day. Over at Columbia, Moe Howard and Larry Fine would soldier doggedly on like George Blanda kicking extra points or Harold Stassen running for president, even as Third Stooges kept dropping dead beside them; but in 1959 even they, like the Disney True Life Adventures, would segue into features for good.

Did audiences sense the end as they sat in theaters, their eyes wandering to the shadow patterns on the curtains behind Martin Block’s desk? I suppose not; right now always feels permanent at the time. But some far-seeing souls with long memories might have reflected that these shorts weren’t nearly as much fun as they used to be. Could they have imagined that fifty, sixty years down the line the Academy would still be doling out Oscars for short subjects — albeit to ones that almost nobody ever sees?

.

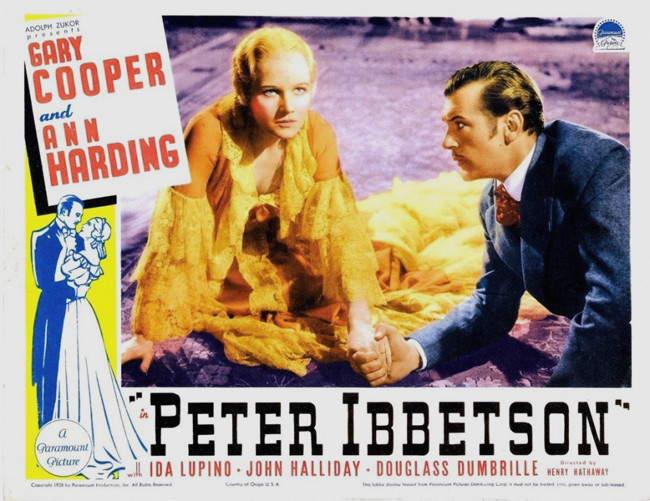

Every now and then in the 1930s (and more often than you might think) the Hollywood factory would turn out a picture that just didn’t fit the mold, one that seems in retrospect out of step with the reigning star system, the house style of its studio, the temper of the times — or a combination of all three. Lewis Milestone’s The General Died at Dawn was like that, and Warner Bros.’ Victorian-ornate A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and 1934’s Death Takes a Holiday. (For that matter, so was King Kong.) “Miracle pictures,” I call them; the fact that they’re as good as they are — that they were made at all — seems almost to violate the laws of Hollywood physics.

Every now and then in the 1930s (and more often than you might think) the Hollywood factory would turn out a picture that just didn’t fit the mold, one that seems in retrospect out of step with the reigning star system, the house style of its studio, the temper of the times — or a combination of all three. Lewis Milestone’s The General Died at Dawn was like that, and Warner Bros.’ Victorian-ornate A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and 1934’s Death Takes a Holiday. (For that matter, so was King Kong.) “Miracle pictures,” I call them; the fact that they’re as good as they are — that they were made at all — seems almost to violate the laws of Hollywood physics.

“You needn’t be afraid, Peter,” she says. “The strangest things are true, and the truest things are strange.”

“You needn’t be afraid, Peter,” she says. “The strangest things are true, and the truest things are strange.” The look of the movie is as sublime as Cooper’s acting. If Lives of a Bengal Lancer shows what Hathaway learned from Victor Fleming, Ibbetson shows the effect of having worked with Josef von Sternberg. Hathaway and Lang modeled their lighting on Rembrandt (“He taught you not to be afraid of the dark.”), and the compositions reinforce the romantic yearnings of the story. See how often the two lovers are separated by iron bars, walls — even, as children, the rails of the cast-iron fence between their homes. When, in dreams, they walk through the bars to be together, it’s a simple trick that any amateur shutterbug could explain to you, but it’s so perfectly right that it takes your breath away.

The look of the movie is as sublime as Cooper’s acting. If Lives of a Bengal Lancer shows what Hathaway learned from Victor Fleming, Ibbetson shows the effect of having worked with Josef von Sternberg. Hathaway and Lang modeled their lighting on Rembrandt (“He taught you not to be afraid of the dark.”), and the compositions reinforce the romantic yearnings of the story. See how often the two lovers are separated by iron bars, walls — even, as children, the rails of the cast-iron fence between their homes. When, in dreams, they walk through the bars to be together, it’s a simple trick that any amateur shutterbug could explain to you, but it’s so perfectly right that it takes your breath away.