On the recording of our inverview, at the point at which Part 2 of these posts ended, Mr. Delgado got up to answer the phone — this was 1970, remember, and when the phone rang you had to answer it. While he was out of the room, Bob, Carol and I agreed that we had probably stayed long enough and were now keeping him from his family. In fact, during our conversation, his adult son had come in from working in the yard (edited out of the transcript) and asked if Mr. Delgado was “going over to Bob’s later on.” It even occurred to us that the phone call Mr. Delgado was answering at that moment might be one of his relatives asking what was keeping him.

The three of us agreed it was about time to wrap up our visit with Mr. Delgado. But before we left, we definitely wanted to have a look at those albums we had glimpsed sitting on the dining room table. I left the tape recorder running while we perused the albums, and what follow are excerpts of that conversation.

JL: (seeing date on picture from Mighty Joe Young) Nineteen-forty-seven! And the film was released in ’49. You worked on it that long? Here’s December of ’47 and here’s July of ’48.

MD: Forty-seven, ’48, yes.

JL: And here’s the burning orphanage. How did you do the fire on that?

MD: Oh, that thing was really on fire.

JL: How big a model was it?

MD: About one inch to the foot. (Ray Harryhausen has said that the orphanage model was about five feet tall – jl)

JL: Here’s the tug-o’-war.

MD: That little model was only four inches high.

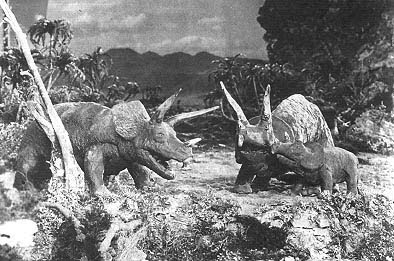

JL: (another picture, another movie) What’s this from?

MD: Dinosaurus! That’s the one that I told you they wanted to shoot next Thursday. So I just made the thing to look like something. It was nothing. I said, “If you want it that way, okay.”

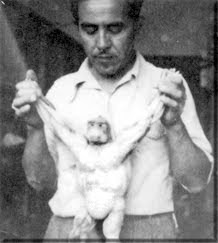

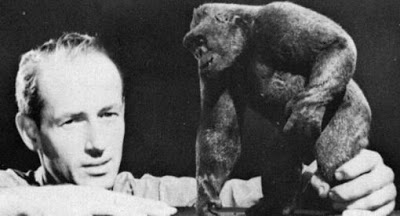

JL: And is this Mighty Joe here?

MD: That’s Mighty Joe. That’s the way they looked when I finished them, before I put the fur on.

JL: (seeing a picture of Delgado with a full-scale model of a hippo) What’s this here? Is this what I think it is?

MD: That’s Disneyland. I worked on Disneyland.

JL: Disneyland? The jungle ride? You worked on the jungle ride at Disneyland?

MD: Just a little bit, not enough to hurt anything, or make any dents on it.

JL: And this is Son of Kong here?

MD: Yes, that’s Son of Kong. You know, that was kind of a little joke.

JL: A joke?

MD: Yes. How could he have a son by Fay Wray? That’s why he was white.

JL: Is this one of your sketches or Mr. O’Brien’s?

MD: No, Byron Crabbe made that.

JL: I understand there’s a gentlemen living up in Chico now who worked on the picture, and he’s working on a book about King Kong.

MD: Who is this?

JL: I can’t remember his name. (reading from the copper cover of the souvenir program) “The picture that staggers the imagination.” When the press agents said all this they didn’t know it was really true.

MD: You know, Jim Danforth bought one of those things about six years ago, and he paid something like $7.00. (Seven dollars!?! The programs I saw on eBay and Hake’s Auctions went for exponentially higher sums. – jl) It’s a wonder that I still have that.

JL: “King Kong opens Thursday, March 16, Grauman’s Chinese.”

(…)

JL: “Technical staff: E.B. Gibson, Marcel Delgado, Fred Reese, Orville …” Orville Goldner, that’s the man who lives in Chico.

MD: Orville Goldner, yes! What was he doing?

JL: I heard that he worked on the animation, and that he’s writing a book about it now. This is why I thought, “Why, that so-and-so, he’s beating me to my idea.”

MD: Orville Goldner, yes. Well, he’s been everything, that Orville Goldner.

JL: What did he do exactly?

MD: I really don’t know what his job was on King Kong. I really don’t know what – What is he classified there?

JL: He’s with you on the technical staff.

MD: I don’t know what he ever did. I really don’t know what was his job.

JL: (reading from the press book) “If Kong stood atop the dizzy tower of the Empire State Building as in the picture, beating his chest with a thunderous din, roaring out in tones audible around the world that his was a remarkable achievement, so should your handling of this picture create such an impression. Twenty-four-sheets (posters – jl) should grow to 48; six-foot enlargements should bound to 60-foot enlargements. There is great entertainment in King Kong; the big showman will go out and sell that entertainment.”

MD: A lot of people are dead already. Eddie Linden is dead, the cameraman. Byron Crabbe is dead, Willis O’Brien is dead, Vernon Walker is dead.

JL: These are your two Kongs, right?

MD: Yeah. They can’t compare, you know, with Mighty Joe for looks. I think Mighty Joe was a better looking monkey. But Kong, the story has more punch than Mighty Joe.

JL: You actually did have a full-size hand and head, right?

MD: Yes.

JL: And feet, did you have feet?

MD: No, just one foot, the foot and the hand. And the head.

JL: In resetting the models between frames, did you use instruments or did you just do it with your fingers?

MD: No, you set it with, just with your fingers.

JL: There’s the full-size bust. Did you have much to do with this one?

MD: Oh, yes.

JL: You designed that too?

MD: I sure did.

JL: You had something like 87 machines inside this thing, operating the muscles?

MD: No, that’s another story. You know, it’s a funny thing, but when I went to see the picture, on that night there was a kid, a young boy, sitting in the back where I was sitting, with a couple of girls. And he was telling these girls everything about how he was up there, he was right on top of King Kong, on top of the head manipulating all these levers. We sure got a kick out of that, my brother and I.

JL: How did you feel when you finally sat there in the theater watching it? Did you feel really proud of yourself?

MD: No, I didn’t have no feeling. It was a job that was over. You know, you don’t know what’s going to happen. I mean, when you worked on a thing like that, you just worked on it, you got paid whatever you got paid. That was it. That’s all it means to you.

JL: Years ago, even before Mr. O’Brien died, there was a man whose name was Charles Gemora, he was a midget, who died in Hollywood. And whenever they needed a gorilla or something in a movie, he’d play the gorilla, he’d get in the gorilla suit because he was a small man – he wasn’t quite a midget, but he was a small man. And when he died, the obituary said that he had “played” King Kong. And I thought, what an insult, to think that that was a man in a suit. But what a compliment, too, to think it was that real.

MD: That’s what they ask me, they ask me all kinds of questions. And I says to them, never was there a man in a suit. They even think that on the climbing, on the climbing of the Empire State Building, that it was a man. They claim that there was a man because they could almost see the structure of a man.

JL: But never at any time –

MD: Never at any time there was a man in a suit. Nobody ever played King Kong in a suit.

JL: Did you paste all these in here at the time or later?

MD: At the time.

JL: (reading from a publicity still caption) “Bruce Cabot clutching Fay Wray to him as the giant ape god Kong, who can squeeze the life out of a human being between his thumb and forefinger, approaches, in Kong, Radio Pictures’ half-fantastic, half-realistic photoplay.” This was obviously an early release, before the title was changed to King Kong.

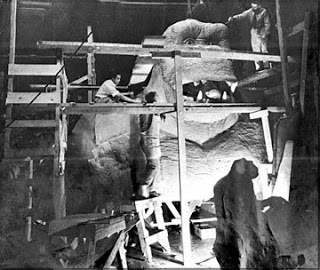

JL: What’s this?

MD: Eagles. War Eagles. That would have been a wonderful picture.

JL: I take it this wasn’t finished?

MD: No, it wasn’t finished, it was shelved.

JL: When was it that this went into production?

MD: Oh, that was in nineteen – 1948, I believe.

JL: How far along did production get before it was shelved?

MD: We just made one sequence, and I don’t even know what became of it. They shelved it because it was the war or something, they were afraid they weren’t going to finish it, so they just shelved it. Which they never reopened it again. [another picture] There’s Jim Danforth.

JL: What’s this on?

MD: That’s – what’s the name, the man with the double head, the monster with the double head – Jack the Giant Killer [1962]. I made the original giant, then when I got it finished, this fellow that was rushing me all the time, he didn’t think it was good enough and he changed it. And the minute I knew that he changed it, I disowned it. They remodeled it and it didn’t look like anything, so I don’t claim that one. But I made the original model for that one.

JL: And this is Mad World, right? Are these your models too?

MD: Yeah, I made the little models.

JL: Did they use your models or did they just rebuild the whole thing?

MD: No, they used my models but they didn’t animate them the way they should have been. You couldn’t see nothing. Couldn’t see nothing at all.

JL: What’s this?

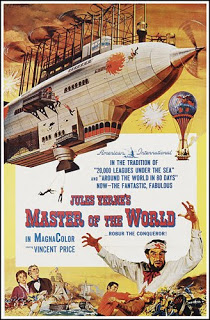

MD: That’s Master of the World.

JL: The Vincent Price picture?

MD: I just worked on the miniatures.

JL: Overall, offhand, could you estimate how many films you have worked on?

MD: Well, I have no idea. I worked 46 years, that I put in pictures. I worked on a lot of them, and I worked mostly all the time.

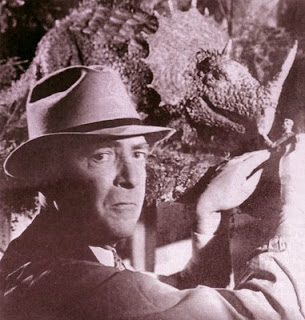

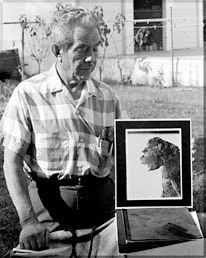

So there it is, the full account of my meeting with Marcel Delgado. It’s with no small sense of relief that I finally get this on the record and off my chest. For 40 years I’ve had this nagging sense of … well, not guilt exactly, but almost. As if I finagled this meeting under false pretenses. It wasn’t false pretenses, really. But pretensions, definitely. It was beyond pretentious of me to think I was up to writing the book I contemplated. But I’m glad I thought so; otherwise I would never have met this remarkable, gentle man.

Some of the illustrations in these posts are the same pictures I saw in Mr. Delgado’s albums, having been subsequently published elsewhere. Others are simply examples to give a sense of what we were talking about. I recall pictures (and you can hear us reacting to them on the tape recording) that I only wish I could share with you now: the model of Kong standing next to an open carpenter’s tape measure; or Mighty Joe Young posed next to a live kitten, both of them staring wide-eyed at the camera; or a picture of the models from It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, clearly (if sketchily) intended to represent Buddy Hackett, Spencer Tracy and Sid Caesar. I wonder where those albums, and that copper-covered program, are now. (And I wonder whatever happened to the scoundrel who cleaned out those albums, leaving only cheap copies of the priceless pictures in them. Nothing good, I hope.)

Marcel Delgado passed away the day after Thanksgiving 1976, 51 days short of his 76th birthday. Ever since I saw the news, I’ve wished I had found a way to publish my interview with him. It was the least I could do, in return for his graciousness and hospitality. And it’s the least I can do now.

JL: It’s funny, if you mention Atlanta nobody thinks of Gone With the Wind, but if you mention the Empire State Building, everybody thinks of King Kong, whether they’ve seen the movie or not. Was there anything at all that struck you as unusual about the film? Fay Wray said that when she first saw the script she thought somebody was playing a practical joke on her. Did it strike you as unusual on that – or on The Lost World for that matter – that a major studio would put a major investment in that kind of movie.

JL: It’s funny, if you mention Atlanta nobody thinks of Gone With the Wind, but if you mention the Empire State Building, everybody thinks of King Kong, whether they’ve seen the movie or not. Was there anything at all that struck you as unusual about the film? Fay Wray said that when she first saw the script she thought somebody was playing a practical joke on her. Did it strike you as unusual on that – or on The Lost World for that matter – that a major studio would put a major investment in that kind of movie.

MD: Yeah, he didn’t have anything to do with that either. And It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, he was there just for his name only.

MD: Yeah, he didn’t have anything to do with that either. And It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, he was there just for his name only. JL: Several scenes that have surfaced that were cut from King Kong – where he’s picking the clothes off Ann, where he finds the wrong girl in New York and drops her, and several others – do you know when those scenes were cut out?

JL: Several scenes that have surfaced that were cut from King Kong – where he’s picking the clothes off Ann, where he finds the wrong girl in New York and drops her, and several others – do you know when those scenes were cut out?

He also had the Holy Grail of movie souvenir programs, the only copy of it I’ve ever seen. Here, just to give you the idea, is a picture of the replica that was included in the deluxe collector’s DVD of Kong that came out in 2005, at the same time as Peter Jackson’s remake.

He also had the Holy Grail of movie souvenir programs, the only copy of it I’ve ever seen. Here, just to give you the idea, is a picture of the replica that was included in the deluxe collector’s DVD of Kong that came out in 2005, at the same time as Peter Jackson’s remake.