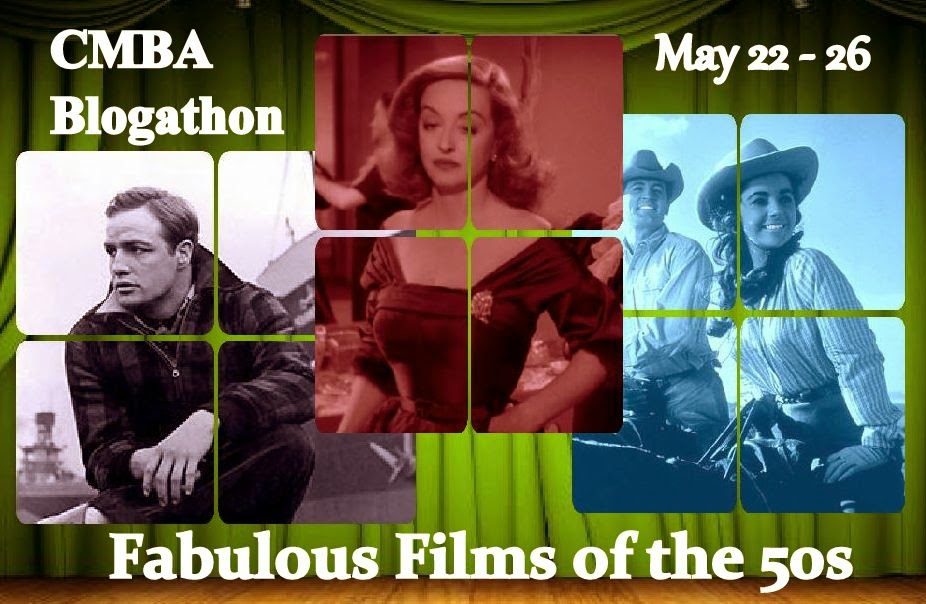

I interrupt my look back at Shirley Temple’s career to offer Cinedrome’s contribution to the Classic Movie Blog Association‘s blogathon Fabulous Films of the 1950s. Go here for a complete list of entries; you’ll find my colleagues holding forth on an impressive array of movies legendary and obscure, long-remembered and half-forgotten.

The ’50s, like the ’40s before (subject of another CMBA blogathon here), were an embarrassment-of-riches period. The Hollywood studio system was dying, it’s true, but that wasn’t so clear at the time; in the second half of the decade especially, the studios seemed to be recovering from the sucker punch of television. There were plenty of terrific movies, three of which are illustrated on the banner here. For Cinedrome’s entry, I’ve decided to follow my customary practice and choose a lesser-known title — one that deserves to be remembered and rediscovered:

* * *

In the mid-1950s Republic Pictures was on its last legs as a movie-producing entity. Formed in 1935, it was the brainchild of Herbert J. Yates, founder and president of Consolidated Film Industries, a film processing lab based in New York. Yates saw his big chance when six of Hollywood’s Poverty Row studios — the largest (relatively speaking) being Monogram and Mascot — became deeply indebted to Consolidated for processing fees. Yates called all their debts, then offered an alternative: merge into one production facility, with Yates as head of the studio. The others went for it, and Republic Pictures was born. (In 1937, unable to get along with Yates, Monogram’s officers backed out of the deal and reorganized under their old corporate name, which morphed in 1947 into Allied Artists.)

In the mid-1950s Republic Pictures was on its last legs as a movie-producing entity. Formed in 1935, it was the brainchild of Herbert J. Yates, founder and president of Consolidated Film Industries, a film processing lab based in New York. Yates saw his big chance when six of Hollywood’s Poverty Row studios — the largest (relatively speaking) being Monogram and Mascot — became deeply indebted to Consolidated for processing fees. Yates called all their debts, then offered an alternative: merge into one production facility, with Yates as head of the studio. The others went for it, and Republic Pictures was born. (In 1937, unable to get along with Yates, Monogram’s officers backed out of the deal and reorganized under their old corporate name, which morphed in 1947 into Allied Artists.)

Strictly speaking, Republic was a notch or two above Poverty Row, but it was never a major operation. Its bread and butter was chapter serials and westerns, its biggest stars John Wayne, Gene Autry, Roy Rogers and Rex Allen (in just about that order). There was the occasional prestige picture (again, relatively speaking), like Sands of Iwo Jima and The Red Pony (both 1949), or, a few more notches up the scale, John Ford’s Rio Grande (’50) and The Quiet Man (’52), but for the most part it was cliffhangers, horse operas and hillbilly comedies for the small-town venues. In the summer of 1955, taking one last shot at prestige, Yates dispatched a unit headlined by Ann Sheridan and Steve Cochran up north to the California Gold Country town of Ione (pronounced “eye-own”) in the hills of Amador County 35 miles southeast of Sacramento. There they made what is surely (with the arguable exception of Orson Welles’s 1948 Macbeth) the best movie ever to come out of Republic Pictures that didn’t involve John Ford or John Wayne. (And no, I’m not forgetting Johnny Guitar.)

Come Next Spring was directed by R.G. (“Bud”) Springsteen. Springsteen was the epitome of the reliable but unexceptional studio workhorse. Actually, “plowhorse” would be more like it; his first directing credit came in 1945, and by the time of Come Next Spring ten years later he had already directed over 50 features — mostly Republic program westerns running about an hour, with a smattering of crime dramas and shoestring musical comedies. At the very least, Springsteen was a man who didn’t waste time, film or money — a triple virtue guaranteed to endear him to the penny-pinching Herbert Yates. It would also earn him a secure niche in television; by the time he retired in 1970 he had a hefty resume consisting of multiple episodes of Gunsmoke, Rawhide, Wanted: Dead or Alive, Wagon Train, Bonanza, Gentle Ben and others.

The secret ingredient of

Come Next Spring was its writer, Montgomery Pittman (shown here in a small role on TV’s

Cheyenne, in an episode he also wrote). Pittman was the kind of talent who might almost be described as “unjustly forgotten today” — except that the sorry truth is he died before even being noticed, succumbing to throat cancer at 42 in 1962. He was prolific, resourceful and original, and what he did accomplish in his brief 11-year career gives a frustrating hint of what might have been if even another ten or 15 years had been granted to him.

Born in Oklahoma in 1920, Pittman left home while still a teenager and, according to his own colorful account, found work with a traveling carnival as (no joke!) a snake-oil salesman. After military service during World War II he landed first in New York, then Los Angeles, with hopes of becoming an actor. Among the odd jobs he took during this time was housecleaning for fellow actor Steve Cochran, then under contract to Sam Goldwyn and beginning to make a name for himself; their friendship would bear fruit with Come Next Spring.

After a few minor movie roles (including one in Inside the Walls of Folsom Prison with his friend and sometimes employer Cochran), Pittman transitioned into writing and eventually, like other writers before him, into directing as a means of protecting his scripts. Along the way, in 1952, he met and married Maurita Gilbert Jackson, a widow whose ten-year-old daughter Sherry was already launched on a career as a child actress. Pittman’s relationship with his new stepdaughter would also bear fruit in Come Next Spring.

In the mid-to-late-’50s Pittman was a contract writer for Warner Bros. Television, where he contributed scripts to the studio’s westerns Cheyenne, Sugarfoot and Maverick, and the private-eye series 77 Sunset Strip (for the latter three he usually directed his scripts as well).

In the early ’60s (and, in fact, just as his time among us was running out) Pittman wrote and directed three episodes for Rod Serling’s original The Twilight Zone on CBS. These jobs are worth mentioning here for several reasons. For one thing, Pittman was the only person during the entire five-year run of the show who both wrote and directed an episode, and he did it three times. For another, those three are among the very best episodes that weren’t written by The Twilight Zone‘s “Big Three” (Serling, Charles Beaumont and Richard Matheson). Finally, and most pertinent to the subject at hand, two of those three contain clear echoes of Come Next Spring: (1) “The Last Rites of Jeff Myrtlebank” — about a young man who springs to life out of the coffin at his own funeral, causing his backwoods neighbors to suspect he ain’t exactly human — takes place in the same time and region as Come Next Spring, and it even features several of the same actors (James Best, Edgar Buchanan, and Pittman’s stepdaughter Sherry Jackson); and (2) “The Grave”, in which bounty hunter Lee Marvin accepts a dare to visit the grave of the outlaw he’s been chasing, not only features James Best again, but it has a female character named Ione — an unmistakable hat-tip to the town where Come Next Spring was filmed.

Come Next Spring

Come Next Spring takes place in 1927 in the hills of Arkansas. We first meet Matt Ballot (Steve Cochran) walking along a country road on a hot summer day. He strikes up a conversation with a little boy he meets (Richard Eyer), and offers to walk along with him a spell, since they both seem to be headed the same way. It turns out that they’re not only headed the same way, they’re headed to the same place. For the boy, Abraham, it’s the farm where he lives. For Matt it’s where he

used to live, before he ran out on his wife Bess and daughter Annie nine years ago. Abraham is the son Matt never knew he had.

Bess (Ann Sheridan) is astonished to see Matt again after all these years, and she makes it plain that the surprise is not a pleasant one. “Why are you here, Matt?” she asks coldly.

Matt tells her he’s been all over the country, and found that whisky tastes pretty much the same everywhere. The last three years he’s been wondering what his wife and daughter were doing, “and I guess I just talked myself into” coming to find out. You never answered my letters, he says; didn’t you get them?

She may have gotten them, but clearly she didn’t read them. I never wanted to see you again, she says; I see no reason to change my mind now. Chastened, Matt is turning to leave when Bess suddenly relents. “I still think you done wrong in comin’ back,” she says, “but the damage is done now. Bein’ as you’re here, I reckon it’s only fair for you to see Annie. So you can stay to supper. If you stay sober.”

Matt assures her that he’s been sober for three years, then he asks about Annie. “Is she…Did she ever get over…?” “Nope,” says Bess, “still mute. Cain’t utter a sound.”

When Abraham returns from washing up, ready to do the milking, Bess hesitates barely a second before telling him who Matt is. “Gee,” says Abraham, “I didn’t even know I had a papa.” Later, when Annie (Sherry Jackson) comes home and warily eyes the stranger in their barn pulling a tick from the cat’s tail, Abraham shares the information, with the pride of a little brother who knows something his big sister doesn’t: “Annie, this here’s our papa!”

That night, Abraham surprises Bess by showing up for supper in his Sunday best: suit, bow tie. Later, as Matt prepares to leave, Bess unbends a little more. It’s a long walk in the dark, she says; Matt can spend the night in Abraham’s room. Even Annie, still shy of this stranger in the house, nods that it’s all right with her.

The next morning Abraham comes to breakfast having for the first time slept through the night without suffering from his “problem” — bedwetting. Even Annie is sorry to see Matt leave. So Bess softens an inch or two more. “I forgot how important a man is to children,” she says — and besides, she could use a hand around the farm. So she offers Matt the job. But that’s all he’ll be — a hired hand, at a dollar a day plus his keep, bunking with Abraham. “All right, Bess,” Matt says, “you hired yourself a hand.”

Matt’s return is greeted by others in the community with little enthusiasm; most of them will offer him no more than a frosty hello — and that only after he’s greeted them first, with their own “hello” signaling an end to the conversation. One of the few who greets him kindly is old Jeff Storys (Walter Brennan), a sharecropper on Bess’s farm who knows nothing of her and Matt’s history. Another, who does know but likes Matt anyway, is the Ballots’ friend and neighbor Mr. Canary (Edgar Buchanan), who urges Matt to have patience: “Look at it like you was one o’ them, Matt, put yourself in their place. What would you a-been thinkin’ the night Abraham was born?” Matt wonders if Canary feels the way they do. “I’ve always felt,” Canary tells him, “that you was a lot more of a man than they gave you credit for. If you’re still around here come next spring, you’ll prove I’m right.”

(This isn’t the first time the movie’s title pops up in the dialogue; the phrase seems part of the local idiom. At one point Abraham asks his mother, “How come people are always sayin’ ‘come next spring’ somethin’s gonna happen?” “Oh, it’s just a saying,” she tells him, “meaning ‘in the springtime’ or ‘not too far away’.” Abraham shrugs. “Seems to me it means it ain’t never gonna get done.”)

One who has particular and personal reasons for disgust at Matt’s return is Leroy Hightower (Sonny Tufts), Canary’s hired hand, who has been futilely trying to court Bess almost since the day Matt walked out on her. Leroy’s not a bad sort at heart, but there’s more than a little of the bully about him, and he talks to (and about) Matt with the snide sarcasm of a frustrated suitor. Leroy believes it’s only a matter of time before Matt falls off the wagon and becomes the same good-for-nothing drunk he was nine years ago — and Leroy’s not above doing his bit to make sure it happens.

Bowen Charles Tufts III is one of Hollywood’s sad cases. He was not without talent, but not talented enough to overcome some unfortunate life and career choices. Born of a prominent Boston family (his great-uncle founded Tufts University), he shunned the family banking business to study opera at Yale. Thanks to his good looks and a college football injury that made him 4-F during World War II, he found stardom in Hollywood when handsome leading men were relatively scarce. Alcohol was his undoing, and his off-screen behavior became notorious. He gave probably his best performance in Come Next Spring, and a few years later he reportedly sobered up in hopes of landing the role of Jim Bowie in John Wayne’s The Alamo. Whether that’s true or not, by that time his name was already a Hollywood punchline, and the idea was probably a non-starter. He died of pneumonia in 1970, age 58.

How Matt Ballot, heeding Mr. Canary’s advice about patience, slowly wins his way back into the love of his family and the respect of his neighbors forms the spine of Come Next Spring. The movie’s emotional centerpiece comes almost exactly halfway through its 93 minutes, when Matt, prompted by a question from Abraham, and knowing the question will never go away, finally explains to Annie why she is unable to talk. “It wasn’t no Act of God like you always been told,” he says to her. “God give you a voice just like everybody else.” Bess tries to stop Matt — by this time even she doesn’t want to see him torn down in the children’s eyes — but Matt forges on. What happened, he tells Annie, was that one night, too drunk to drive and too belligerent to let Bess take the wheel, he drove their car off the road and wrecked it. Bess and Matt walked away unhurt, but the traumatic shock left Annie unable to speak — or to make any sound at all — from that day to this.

There are still crises to come for Matt, Bess and the children — a cyclone that devastates their farm, a long-simmering showdown with Leroy, a frightening disappearance by one of the kids — but how it all plays out is something best discovered by seeing the movie itself.

When she made Come Next Spring, Ann Sheridan was 40, several years past her glamour days as Warner Bros.’ “Oomph Girl” (a nickname she loathed). Even at the height of her career at Warners, her talent never got the respect it deserved — not surprising for a studio dominated by its male stars that already had Bette Davis and Olivia de Havilland. But she was an actress of considerable — even remarkable — depth and range. She demonstrated this to anyone who cared to notice during the fall of 1941, when she was shooting two pictures simultaneously: She worked mornings on the raucous farce The Man Who Came to Dinner (and was one of the funniest things in it), then after lunch she reported to the set of the brooding, dark melodrama Kings Row. All through World War II she was well-liked by co-workers, popular with audiences, and underrated by critics. That combination held all the way through her untimely death at 51 in 1967 (and the “underrated” part has stayed with her ever since).

Sheridan’s Bess Ballot is a woman who has had self-sufficiency thrust upon her by the only man she’s ever loved, and the experience has made her stern almost to the point of harshness. When Matt’s wandering brings him back into her life, her defenses instantly fly up — because the sight of him, in spite of everything, still makes her weak in the knees. We can see it, even if she can’t, in the way she softens every time Matt is on the verge of leaving again: First she says he can stay for supper, then till morning, then till “come next spring” as a hired hand. This always-underrated actress was never better than she was as the resolute, wounded Bess.

Steve Cochran, unlike Sheridan, was never underrated — exactly. But ever since his sudden death from a lung infection at 48 in 1965, the question has haunted movie buffs: Why didn’t this guy ever become a bigger star? Part of it may have been his tabloid lifestyle of womanizing, carousing and boozing, flying in the face of his fragile health (he had a heart murmur that kept him out of the service during World War II). Or it may have been because he never managed to break the mold of gangsters, thugs and unsavories into which he had been typecast, certainly not the way other actors — Robert Mitchum and Dana Andrews, for instance — had been able to do. Still, he never really gave a bad performance even in the most ill-chosen of his 39 pictures; he was clearly an actor of substance (on stage he had played Orsino in Twelfth Night, Horatio in Hamlet, even Richard III). In Matt Ballot, Cochran gives us a good man who has been beaten down by an ill-spent life and the consequences of his own bad decisions, and who now hopes only to pull himself together before it’s too late. It was the role, and the performance, of Cochran’s life, and he knew it. When Monty Pittman brought him the script, Cochran bought it for his own company, Robert Alexander Productions (named for his real first and middle names), then sold it to Republic on the condition that he and Sherry Jackson play the roles that had been written for them. If Cochran had given this performance for any studio but Republic it might have made all the difference in the arc of his career. But the truth is that probably no other studio would have cast him as anything but a ne’er-do-well or a hood — Matt Ballot, if you will, unrepentant and unreformed. It may even be that no other studio would have touched Come Next Spring at all. That, sad to say, was just Steve Cochran’s luck.

As if Ann Sheridan, and Steve Cochran, and Montgomery Pittman’s intelligent and perceptive script were not enough, there’s another excellent reason to see

Come Next Spring, one that all by itself would be more than enough: the extraordinary performance of 13-year-old Sherry Jackson. If Pittman’s script was intended as a showcase for his friend Cochran, it seems to have been equally intended to give Pittman’s own stepdaughter the role of a lifetime. Even by the time Pittman married her mother in 1952, Sherry was already a veteran of more than 15 feature films. Mostly uncredited bits, but more substantial roles were ahead: one of the visionary Portuguese children in

The Miracle of Our Lady of Fatima (’52), John Wayne’s daughter in

Trouble Along the Way (’53). When shooting started on

Come Next Spring, Sherry was coming off her second season as Danny Thomas’s oldest daughter on

Make Room for Daddy.

As the shy and withdrawn Annie — “around the animals so much,” her mother says, “she’s beginning to act like one” — Sherry Jackson is thoughtful, watchful and wary. With her enormous — and enormously expressive — eyes, and with every tiny movement of the corners of her mouth, she makes Annie’s every fleeting thought as plain as if she spoke them out loud. And she does it without making a sound. Jane Wyman in Johnny Belinda won an Oscar (and rightly so) for doing not much more than Sherry Jackson does in Come Next Spring. It is, without question, one of the greatest child performances ever put on film.

Ann Sheridan, Steve Cochran, Sonny Tufts, Sherry Jackson. All of them were never better — maybe even never as good — as they were in Come Next Spring. Hmmm. Maybe this Bud Springsteen was a better director than he ever got credit for.

* * *

When it played host to the Come Next Spring company in 1955, Ione, Calif. was a small foothill community of perhaps 1,500 people. It’s grown somewhat in the 59 years since then, but not as much as you might think. The population now hovers around 4,200 (not counting the nearby Mule Creek State Prison, whose 3,000 inmates are technically “residents” of Ione). The town itself has changed even less than the population. Even allowing for its being dressed to resemble Arkansas 30 years earlier — with its fleet of Model A and Model T Fords, the vehicles of choice for small farmers in the 1920s — the Ione of Come Next Spring is still visible in the Ione of 2014. (NOTE: I am indebted to City Clerk Janice Traverso and her co-workers in the Ione City Hall, and to local resident Doug Hawkins, who played a small role in the picture at the age of 11, for their assistance in finding and photographing locations for Come Next Spring.)

This is Main Street of (the fictitious) Cushin, Arkansas as the Ballot family drives into town on Saturday to do their weekly shopping. That’s them on the right in their Model T — Matt driving, with Annie (holding her hat) and Bess in the back seat. That imposing-looking two-story building is actually the meeting hall of Ione Parlor 33 of the Native Sons of the Golden West…

…and it’s still there today, not much changed except for the removal of that out-of-control ivy on the eastern wall.

One block west and on the other side of Main Street, this building…

…has had a facelift since 1955 — probably more than one, as a matter of fact — but it’s still recognizable. Pretty much.

On the other hand, this stretch of sidewalk where a group of boys (including Doug Hawkins’s classmate Guy Campbell, a local boy who still lives in Ione) are taunting Annie as the town “dummy”…

…well, that’s hardly changed at all.

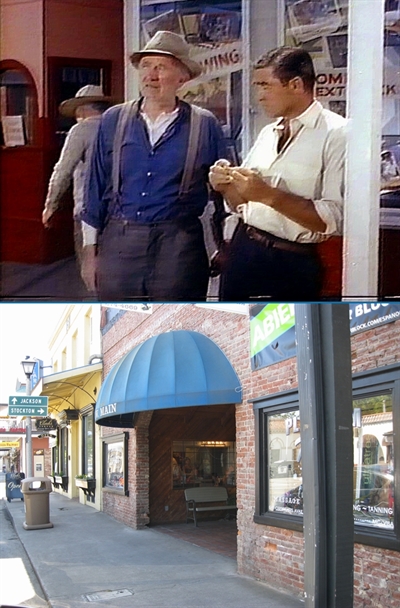

Here are Jeff Storys and Matt standing outside the town’s picture show chewing the fat (presumably the Ione Theatre’s display cases have been changed to reflect what might have been “now showing” and “coming next week” in 1927). Doug Hawkins remembers seeing Come Next Spring in this theater. That was no doubt a sneak preview for citizens of the host town; the picture’s world premiere was held at the Amador Theatre in nearby Jackson, the Amador County seat (and mighty big news that was in Jackson, believe you me). The Amador is gone now; where it stood is now the parking lot of the Jackson branch of El Dorado Savings…

…and the Ione Theatre is also gone, gutted by fire decades ago. The space is now a mini-mall housing a hair salon, a massage-and-tanning parlor, and other local businesses.

This locomotive is “Iron Ivan”. In 1955 it was the last steam engine operating on the Amador Central Railroad, a short (approx. 12 miles) line that operated entirely within the borders of Amador County. Ivan made this cameo appearance in a brief scene showing the area’s farmers arriving with their milk and eggs to ship them off to market. Iron Ivan was retired in 1956, not long after this scene was filmed…

…and rests now on permanent display in the Ione City Park.

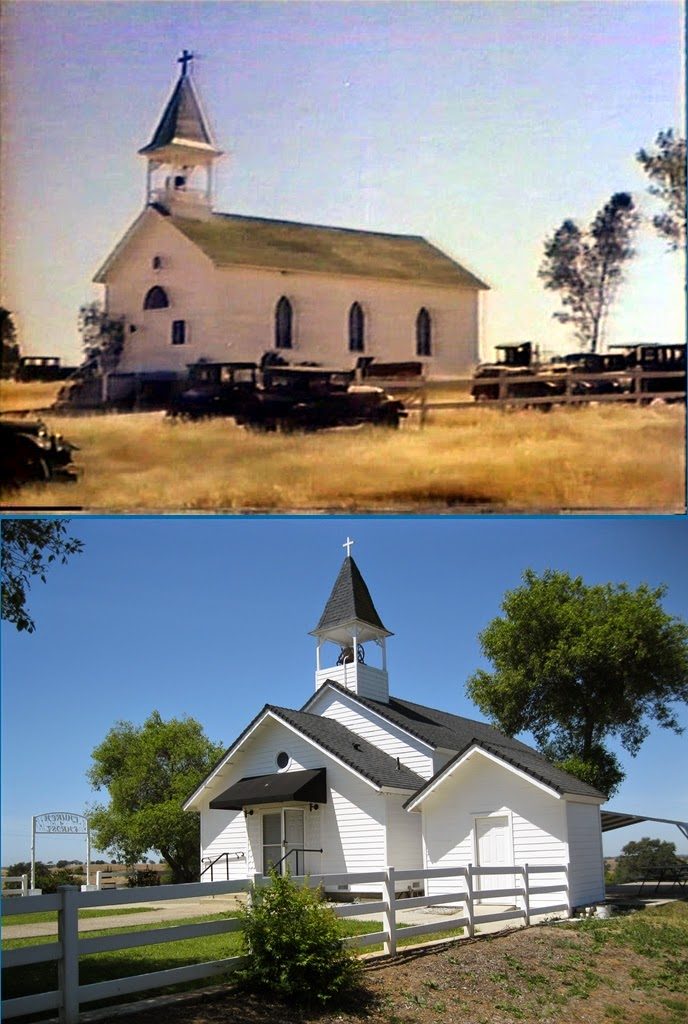

This on the right is the little country church where the Ballots and their neighbors worship. It is from these windows, during a Sunday morning sermon on the evils of drink, that the congregation first notices the approach of cyclone weather. And it’s here that Matt literally seizes the reins and stems a rising panic in the parking lot as worshipers dash madly out to their wagons and autos to try to save what they can of their homes.

In 1955 this church was in the tiny community of Camanche, about five miles south of Ione. Today, Camanche is at the bottom of Camanche Reservoir, created when an earthfill dam was completed across the Mokelumne River in 1963. (For you non-Californians out there, the river’s name is pronounced “McCullumy”.)

The church, however, was moved to higher ground, where it stands today overlooking the north shore of the reservoir — with the addition of a newer entry vestibule and storage shed.

As I mentioned before, the mainspring of Come Next Spring is Monty Pittman’s pitch-perfect script. It tells an unusual yet simple and straightforward story without a wasted word or a false note. Even its minor characters — for example, Harry Shannon as neighbor Tom Totter (that’s him a few pictures up giving Matt Ballot the cold shoulder at the railroad siding), Wade Ruby as the preacher Delbert Meaner, and Roscoe Ates as Shorty Wilkins, the local moonshiner — are sketched in sharp detail with a few deft strokes. Sometimes only a few lines are all it takes to tell us what we need to know about these people — and Pittman knew the right few lines. Then there are the sensitive performances, and the typically emotional musical score by the great Max Steiner (including a title song written with Lenny Adelson that was a popular hit for Tony Bennett, who sings it under the credits).

Come Next Spring has been going in and out of print for over 30 years, ever since the dawn of the home video age. As near as I’ve been able to determine, it’s currently out. But the good news is that it’s

not unavailable. It can be had for streaming

here at Amazon Instant Video — it’s even free if you subscribe to Amazon Prime. (

UPDATE 7/29/22: Sorry, it’s no longer free to Prime subscribers, alas. But it’s well worth the $3.99 to rent or the $12.99 to buy.)

So here’s a challenge for my Cinedrome readers. As soon as you finish reading this post — or as soon as you have 93 spare minutes — click over to Amazon Instant Video (

here’s the link again, just to double-dog-dare you) and treat yourself to

Come Next Spring. Do yourself a favor.

And one last thing. This is a promise: The very last shot of the picture, just before it fades to “The End”, is something you will remember as long as you live. Mark my words.

In the mid-1950s Republic Pictures was on its last legs as a movie-producing entity. Formed in 1935, it was the brainchild of Herbert J. Yates, founder and president of Consolidated Film Industries, a film processing lab based in New York. Yates saw his big chance when six of Hollywood’s Poverty Row studios — the largest (relatively speaking) being Monogram and Mascot — became deeply indebted to Consolidated for processing fees. Yates called all their debts, then offered an alternative: merge into one production facility, with Yates as head of the studio. The others went for it, and Republic Pictures was born. (In 1937, unable to get along with Yates, Monogram’s officers backed out of the deal and reorganized under their old corporate name, which morphed in 1947 into Allied Artists.)

In the mid-1950s Republic Pictures was on its last legs as a movie-producing entity. Formed in 1935, it was the brainchild of Herbert J. Yates, founder and president of Consolidated Film Industries, a film processing lab based in New York. Yates saw his big chance when six of Hollywood’s Poverty Row studios — the largest (relatively speaking) being Monogram and Mascot — became deeply indebted to Consolidated for processing fees. Yates called all their debts, then offered an alternative: merge into one production facility, with Yates as head of the studio. The others went for it, and Republic Pictures was born. (In 1937, unable to get along with Yates, Monogram’s officers backed out of the deal and reorganized under their old corporate name, which morphed in 1947 into Allied Artists.) The secret ingredient of Come Next Spring was its writer, Montgomery Pittman (shown here in a small role on TV’s Cheyenne, in an episode he also wrote). Pittman was the kind of talent who might almost be described as “unjustly forgotten today” — except that the sorry truth is he died before even being noticed, succumbing to throat cancer at 42 in 1962. He was prolific, resourceful and original, and what he did accomplish in his brief 11-year career gives a frustrating hint of what might have been if even another ten or 15 years had been granted to him.

The secret ingredient of Come Next Spring was its writer, Montgomery Pittman (shown here in a small role on TV’s Cheyenne, in an episode he also wrote). Pittman was the kind of talent who might almost be described as “unjustly forgotten today” — except that the sorry truth is he died before even being noticed, succumbing to throat cancer at 42 in 1962. He was prolific, resourceful and original, and what he did accomplish in his brief 11-year career gives a frustrating hint of what might have been if even another ten or 15 years had been granted to him. Come Next Spring takes place in 1927 in the hills of Arkansas. We first meet Matt Ballot (Steve Cochran) walking along a country road on a hot summer day. He strikes up a conversation with a little boy he meets (Richard Eyer), and offers to walk along with him a spell, since they both seem to be headed the same way. It turns out that they’re not only headed the same way, they’re headed to the same place. For the boy, Abraham, it’s the farm where he lives. For Matt it’s where he used to live, before he ran out on his wife Bess and daughter Annie nine years ago. Abraham is the son Matt never knew he had.

Come Next Spring takes place in 1927 in the hills of Arkansas. We first meet Matt Ballot (Steve Cochran) walking along a country road on a hot summer day. He strikes up a conversation with a little boy he meets (Richard Eyer), and offers to walk along with him a spell, since they both seem to be headed the same way. It turns out that they’re not only headed the same way, they’re headed to the same place. For the boy, Abraham, it’s the farm where he lives. For Matt it’s where he used to live, before he ran out on his wife Bess and daughter Annie nine years ago. Abraham is the son Matt never knew he had.

One who has particular and personal reasons for disgust at Matt’s return is Leroy Hightower (Sonny Tufts), Canary’s hired hand, who has been futilely trying to court Bess almost since the day Matt walked out on her. Leroy’s not a bad sort at heart, but there’s more than a little of the bully about him, and he talks to (and about) Matt with the snide sarcasm of a frustrated suitor. Leroy believes it’s only a matter of time before Matt falls off the wagon and becomes the same good-for-nothing drunk he was nine years ago — and Leroy’s not above doing his bit to make sure it happens.

One who has particular and personal reasons for disgust at Matt’s return is Leroy Hightower (Sonny Tufts), Canary’s hired hand, who has been futilely trying to court Bess almost since the day Matt walked out on her. Leroy’s not a bad sort at heart, but there’s more than a little of the bully about him, and he talks to (and about) Matt with the snide sarcasm of a frustrated suitor. Leroy believes it’s only a matter of time before Matt falls off the wagon and becomes the same good-for-nothing drunk he was nine years ago — and Leroy’s not above doing his bit to make sure it happens.

As if Ann Sheridan, and Steve Cochran, and Montgomery Pittman’s intelligent and perceptive script were not enough, there’s another excellent reason to see Come Next Spring, one that all by itself would be more than enough: the extraordinary performance of 13-year-old Sherry Jackson. If Pittman’s script was intended as a showcase for his friend Cochran, it seems to have been equally intended to give Pittman’s own stepdaughter the role of a lifetime. Even by the time Pittman married her mother in 1952, Sherry was already a veteran of more than 15 feature films. Mostly uncredited bits, but more substantial roles were ahead: one of the visionary Portuguese children in The Miracle of Our Lady of Fatima (’52), John Wayne’s daughter in Trouble Along the Way (’53). When shooting started on Come Next Spring, Sherry was coming off her second season as Danny Thomas’s oldest daughter on Make Room for Daddy.

As if Ann Sheridan, and Steve Cochran, and Montgomery Pittman’s intelligent and perceptive script were not enough, there’s another excellent reason to see Come Next Spring, one that all by itself would be more than enough: the extraordinary performance of 13-year-old Sherry Jackson. If Pittman’s script was intended as a showcase for his friend Cochran, it seems to have been equally intended to give Pittman’s own stepdaughter the role of a lifetime. Even by the time Pittman married her mother in 1952, Sherry was already a veteran of more than 15 feature films. Mostly uncredited bits, but more substantial roles were ahead: one of the visionary Portuguese children in The Miracle of Our Lady of Fatima (’52), John Wayne’s daughter in Trouble Along the Way (’53). When shooting started on Come Next Spring, Sherry was coming off her second season as Danny Thomas’s oldest daughter on Make Room for Daddy.

Thank you for your nice comments about my video (I'm very glad you liked it), and for providing the link. I would have tried to provide it myself, but: #1. I didn't want to seem like a spammer; #2. I'm not sure I'd know how to do it! 😉

Thanks for sharing that funny story about how the name of Montgomery Pittman came to be emblazoned on your mind. That would have done it for me too! Efrem Zimbalist Jr. judged Pittman by his 'cover' when they first met in the Warner Brothers commissary. He thought: this frowsy, cigar-chewing frump with a hillbilly accent is writing a script for me? But when he got the script, and began working with Pittman as director, he quickly saw how wrong he was!

And oh, may I add that I love your "then" and "now" comparison shots of the locations? Simply fascinating!

Welcome, Maricatrin, and thanks for commenting. You put me in mind of how I first became aware of Monty Pittman myself. The story wasn't germane to a discussion of Come Next Spring so I didn't include it in my post, but here it is:

In 1959 my movie-buff uncle and my 11-year-old self were watching an episode of the syndicated western series The Rough Riders when I noticed the director credit. I don't know why, but there was something that just struck me as puffed-up about the name, so I said, with elaborate sarcasm, "Ooh, look, it was directed by Montgomery Pittman!" Imagine my chagrin when my uncle gently chided me, "Actually, Montgomery Pittman is highly respected and considered one of the best writers in television." I think my ears actually burned; I was absolutely flabbergasted at the thought that anybody, let alone my own uncle, had ever heard of this Pittman guy. It was a valuable (if mortifying) lesson about never judging a book by its cover — or a talent by the name it came with.

Needless to say, that experience burned the name of Montgomery Pittman indelibly into my memory. And like you, I suddenly started noticing it everywhere: episodes of Maverick, 77 Sunset Strip, The Twilight Zone — and, eventually, on Come Next Spring. Looking back, I realized that when my uncle said what he said, he must have had Come Next Spring in mind; he was living in the neighboring county in 1956 and attended the picture's world premiere in Jackson.

Kudos, too, Maricatrin, on your video for Come Next Spring/"Don't Stop Lovin' Me Now"; a very nice job, and a fitting tribute to both. I urge my readers to check it out by clicking here.

I'm glad to see Montgomery Pittman has some fans besides myself! I kept noticing his name on the credits of tv show episodes which were particularly good. Efrem Zimbalist Jr. gives Pittman his due in his autobiography, saying Pittman was the most talented writer who worked on 77 Sunset Strip. Pittman also wrote a hilarious episode of The Rifleman, which Sherry Jackson appeared in.

I've seen "Come Next Spring", and it was everything you say it is. And I've just now completed a music video for the film, utilizing the Don Williams song: "Don't Stop Loving Me Now." I hope it will help interest yet more people in the film.

I attended this social drama,even in the 70',the defunct TV Itacolomi(Passa Tempo in Minas Gerais/Brazil).I'm a "fan" of Sherry Jackson,and a great admiration for the actor Walter Brennan.The screenwriter Montgomery Pittman,was the stepfather Shery.

Jim,

I'm glad you chose a lesser known film. One I haven't had the pleasure of seeing.

Just an enjoyable read from start to finish. Such interesting info you've provided on Republic then Mr. Springsteen. All this before even getting into the stars of the film then the wonderful review. You see films like no other and you give me so much insight into how a film is made from the ground up.

Like Jeff, I do hope CNS finds it way to DVD.

The perfect contribution to our little Blogathon.

All the best!

Page