I’m home from Columbus, Ohio and more or less decompressed from spending four days at Cinevent, so I think I’m ready to give a quick rundown of the highlights I saw there. The Midwest’s venerable Classic Film Convention is always an embarrassment of riches, some of them quite obscure. It’s hard not to feel movie after movie passing in a sort of blur. Still, some stand out.

* * *

Day 1 – Friday

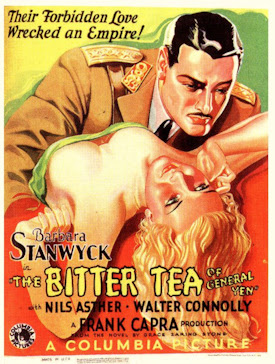

Any day that includes a screening of Frank Capra’s The Bitter Tea of General Yen is bound to be dominated by that delirious Orientalist melodrama. The picture was chosen to open the Radio City Music Hall in 1933, but it performed so poorly that Music Hall management yanked it halfway through its contracted two-week run. The fervid theme of interracial sexual attraction packs a punch even today, even with the “Chinese” warlord played by Scandinavian Nils Asther, and it made ’em positively squirm 80 years ago — those who showed up at all. Barbara Stanwyck played the naive American missionary in the thrall of Asther’s General Yen (that picture on the poster doesn’t look much like her, does it?), but it’s the all-but-forgotten Asther who dominates the picture, in a performance of grace, intelligence and dignity that (like Luise Rainer’s O-Lan in The Good Earth four years later) wins over all but the most rigidly PC viewers today.

Other highlights of the day (for me, at least):

The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T (’53), the Dr. Seuss fantasy that, in its way, was just as delirious as General Yen — and just as big a flop. (As film historian and biographer Scott Eyman said as we discussed the picture over breakfast that morning, “Yeah, [producer] Stanley Kramer lost a lot of money for Columbia.”) Still, Dr. T has found its audience over the last 60 years (though too late to do Columbia any good), and I’ve always had a soft spot for it. I still laugh out loud when, after the “whammy duel” between Peter Lind Hayes and Hans Conried, the two men collapse exhausted into each other’s arms: Conried: “Where did you study??” Hayes: “I just picked it up.”

The 1932 Fox western The Golden West, with an epic Zane Grey story that strained at the picture’s modest 74-minute running time, told the saga of two generations of star-crossed lovers, with George O’Brien playing the male half in both generations (and with an ultimately happy ending). This one featured an unusual supporting character: an Irish-Jewish peddler named Dennis Epstein (played by Bert Hanlon). There was also a buffalo stampede that was a real pip — thanks to the generous insertion of stock footage from The Iron Horse, The Big Trail and other Fox westerns.

* * *

Day 2 – Saturday

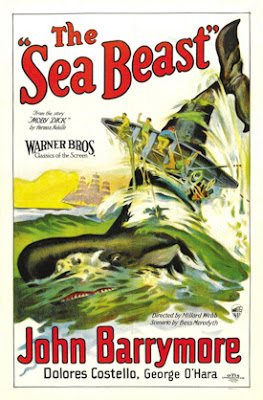

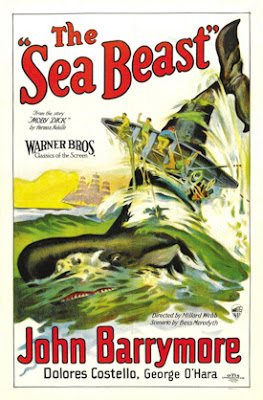

Saturday’s headliner looked at first to be the 1926 silent The Sea Beast, even though it’s exactly the kind of movie that gives Hollywood a bad name. The Sea Beast was ostensibly an adaptation of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, which by the 1920s was finally coming into its own as a pinnacle of American literature. But no pinnacle is so high that somebody can’t be knocked off of it, and that’s what writers Bess Meredyth and Rupert Hughes proceeded to do, supplying Melville with all the things he neglected to write back in 1851. Capt. Ahab’s last name for example: they decided it was Ceeley. And what’s a man without a woman, right? So they gave their Ahab (John Barrymore) a sweetheart named Esther, who by a remarkable coincidence was played by Barrymore’s real-life squeeze (and future ex-wife) Dolores Costello. Then, to add the dramatic conflict that was missing in all that business about the White Whale, they invented Derek Ceeley (George O’Hara), Ahab’s brother and rival for Esther’s affections. The result was, as Richard M. Roberts succinctly put it in his Cinevent program notes, “a REALLY Stupid movie.” Having seen the later (1930) talkie remake Moby Dick (also starring Barrymore, and where the title was the only shred of Melville to be restored), I thought I’d give this one a look for the sake of completeness. Alas, I wasn’t man enough. I got only as far as Ahab’s first run-in with Moby Dick and the line (in an intertitle, of course) “My leg! My leg! He tore it off!” — and decided I simply didn’t need to see any more. The Sea Beast and its 1930 remake may well represent the rock-bottom worst of Hollywood in general, and of Warner Bros. in particular: They got two chances to have John Barrymore, the greatest actor of his age, play Melville’s titanic Capt. Ahab — and they blew it both times. (To be fair, The Sea Beast was a box-office hit, whereas when Warners and director John Huston tried to do right by Melville 30 years later, that version of Moby Dick flopped. So you have to blame the audience as much as Hollywood or Warner Bros.)

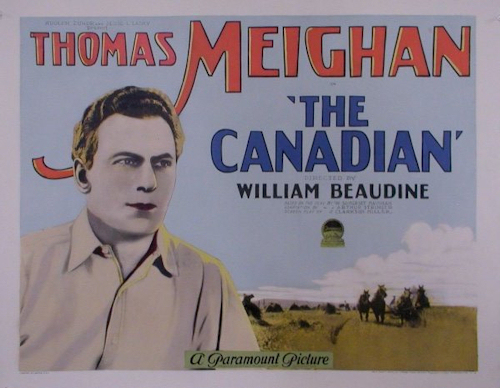

Upstaging The Sea Beast, and just about everything else shown at Cinevent this year, was a real discovery, an absolute bolt out of nowhere, a picture almost nobody had ever heard of. It was The Canadian (1926), directed by none other than William Beaudine. Yes, the notorious “One-Shot” Beaudine, who cranked out some 368 features, shorts and TV episodes over his 53-year career — including the sexploitation “documentary” Mom and Dad (’45) and, towards the end of his run, the camp titles Billy the Kid Vs. Dracula and Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter (both ’66). But back in the ’20s, Beaudine was a director to reckon with, and The Canadian shows why. It’s a simple story: Young Englishwoman Nora Marsh (Mona Palma) is left penniless at the death of the aunt she’s been living with, and has no choice but to emigrate to Canada, where her brother is a struggling farmer on the frontier of western Ontario. Pampered, stuck-up and generally useless, Nora clashes with her brother’s no-nonsense wife, until at length the wife lays down an either-she-goes-or-I-go ultimatum. Nora impulsively marries Frank Taylor, a neighboring farmer (Thomas Meighan), and the rest of the picture tells how this prissy little snob learns to carry her weight in her new household, where she and her stranger/husband slowly grow to love each other.

Upstaging The Sea Beast, and just about everything else shown at Cinevent this year, was a real discovery, an absolute bolt out of nowhere, a picture almost nobody had ever heard of. It was The Canadian (1926), directed by none other than William Beaudine. Yes, the notorious “One-Shot” Beaudine, who cranked out some 368 features, shorts and TV episodes over his 53-year career — including the sexploitation “documentary” Mom and Dad (’45) and, towards the end of his run, the camp titles Billy the Kid Vs. Dracula and Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter (both ’66). But back in the ’20s, Beaudine was a director to reckon with, and The Canadian shows why. It’s a simple story: Young Englishwoman Nora Marsh (Mona Palma) is left penniless at the death of the aunt she’s been living with, and has no choice but to emigrate to Canada, where her brother is a struggling farmer on the frontier of western Ontario. Pampered, stuck-up and generally useless, Nora clashes with her brother’s no-nonsense wife, until at length the wife lays down an either-she-goes-or-I-go ultimatum. Nora impulsively marries Frank Taylor, a neighboring farmer (Thomas Meighan), and the rest of the picture tells how this prissy little snob learns to carry her weight in her new household, where she and her stranger/husband slowly grow to love each other.

Based on Somerset Maugham’s play The Land of Promise, The Canadian was actually a remake; it was first filmed in 1917 under Maugham’s original title, with Thomas Meighan playing the same role (opposite Billie Burke). By 1926, Meighan was a well-established and popular star, billed above the title (and with the title changed to give him the title role), and he’s certainly good in The Canadian.

But the picture belongs entirely to Mona Palma as Nora (shown here with Meighan’s Frank early in their hasty marriage). She gives one of the most remarkable performances of the entire silent era — subtle, sensitive and finely tuned; her face is as immobile as Buster Keaton’s, and yet (as with Keaton) you always know exactly what she’s thinking. Frankly, for much of the first half of the picture, those thoughts aren’t pleasant, and Nora Marsh isn’t very sympathetic; as she gradually grows up and shoulders the responsibilities of her new hardscrabble life — as Nora Marsh becomes Nora Taylor — she wins our sympathy just as she wins over the other characters in the picture. It’s simply an amazing performance. Alas, it’s virtually all we have of Mona Palma. She made only seven pictures in her four-year career (three under her real name, Mimi Palmieri). The Canadian was her big break and first lead, but she made only one more picture (Cabaret, 1927) before retiring from the screen at age 29. She lived to the ripe old age of 91 but never made another movie.

The Canadian survives almost by accident, according to Richard Roberts’s program notes. Paramount’s nitrate print was donated in 1969 to the fledgling UCLA Film Archive, who refused it because it was a silent; it went instead to the American Film Institute, who preserved it. The AFI screened it at the L.A. County Museum of Art in February 1970 as part of its “Rediscovering American Cinema” program. The guest of honor was director Beaudine, seeing the picture for the first time ever. At the thunderous standing ovation afterward, Roberts tells us, the old man wiped away a tear. “I’m very surprised. I was quite a good director once.” A month later, William Beaudine was dead. (I wonder if anybody thought to drive up to Oxnard, Calif. and invite 72-year-old Mrs. Mimi P. Cooper, the former Mona Palma, to the screening as well. Evidently not.)

* * *

Day 3 – Sunday

By Sunday, things are generally beginning to wind down at Cinevent; this year, certainly, The Canadian cast a shadow that the rest of the film program was hard-pressed to live up to. There were a couple of high-profile silents on view this day.

First was The Nut (1921), Douglas Fairbanks’s last modern-dress comedy before devoting himself entirely to the costume swashbucklers that began with The Mark of Zorro (’20), and for which he’s best remembered today. The Nut was…well, if somebody asked me what was the big deal about Doug Fairbanks, this isn’t the picture I’d refer them to to find out. The Obnoxious Schmuck would be a better title, I think, as Doug plays an overbearing inventor whose every effort to win the heart of his beloved backfires in spectacular and embarrassing fashion. The program notes called the picture “episodic”; I’d call it “monotonous”, with the irrepressible Doug’s character decidedly off-putting.

Then there was Stella Maris (1918), one of Mary Pickford’s biggest successes. She plays a dual role: as the title character, a cheerfully sheltered and pampered heiress confined to a wheelchair by some mysterious unnamed disability; and as Unity Blake, a pitifully mistreated orphan whose harsh life contrasts sharply with that of the silver-spooned Stella. It’s a very well-made picture and Pickford is excellent in it, plus there are some first-rate effects when both her characters appear on screen together. But the story itself, from a 1913 novel by William J. Locke, is a specimen of the kind of sickly Victorian melodrama that was going out of fashion even then, and that only a star of Pickford’s caliber could pull off.

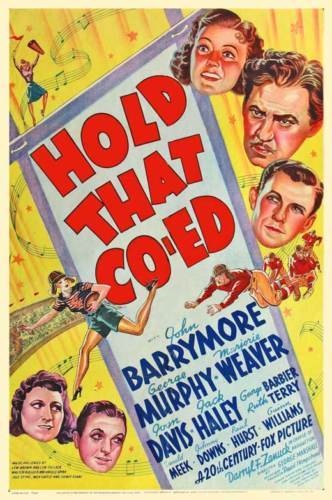

Probably the highlight of the day — and certainly the most fun — was Hold That Co-ed, a 1938 musical with John Barrymore as a Huey Long-ish governor running for the U.S. Senate while simultaneously (and corruptly) trying to wangle a national championship for his pet college football team. Barrymore is a full-throated hoot, the songs are pleasant, and the supporting cast (George Murphy, Marjorie Weaver, Joan Davis, Jack Haley, George Barbier) delightful.

Other memorable Sunday titles: Nazi Agent (’42), with Conrad Veidt (Casablanca‘s Major Strasser) as a naturalized German-American taking the place of his Nazi spy identical twin brother; The Man Who Lost Himself (’41), another lookalikes-switch-identities drama, this time with Brian Aherne replacing his double, the tycoon husband of Kay Francis; and The Disciple (’15), one of William S. Hart’s early westerns, more a strong domestic drama than shoot-’em-up, with Hart a frontier parson determined to clean up a sinful town, even as his wife succumbs to local temptations.

* * *

Day 4 – Monday

And so we come to the last day — or half-day, really. As usual, most of the dealers have packed up and left, as has a large percentage of the attendees. Still, there are pleasures to be had for those (like me) who choose to stay to the bittersweet end. I think my favorite was The House of Fear (1939) — not to be confused with the Basil Rathbone-Nigel Bruce Sherlock Holmes picture with the same title. This one is a niftly little mystery with police detective William Gargan posing as a theater producer to crack a year-old cold case in which an actor was murdered onstage during his opening night performance. Other titles on Monday were The Social Secretary (’16), a silent romantic comedy with Norma Talmadge at her most charming; and Henry Aldrich, Editor (’42), in which our Andy Hardy/Archie clone hero (Jimmy Lydon) tries to run his school newspaper, only to get in hot water over an arson investigation. These Aldrich comedies have been running for a couple of years now at Cinevent, and they’re always pleasant, well-made comedies. This one, according to the program notes, is widely considered the best of the series, and I’m not surprised.

The movies are only part of the fun at Cinevent, of course. There are also the dealers’ rooms, where you can find a vast array of items for sale — film, video, books, stills, posters, lobby cards, magazines, sheet music, souvenir programs and other memorabilia. As always, I stocked up on much of this — and, as always, I didn’t realize how much I’d bought until I had to pack it all up to come home. I get quite a bit of exercise dragging my luggage through airport security and heaving it up into overhead compartments.

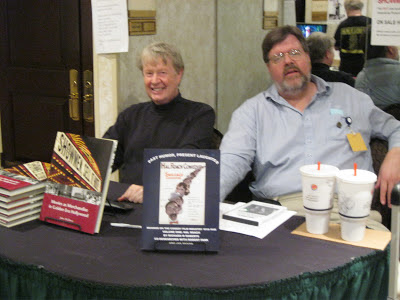

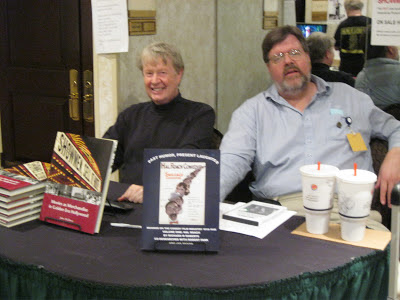

Then there are the people themselves, who have become good friends, a cozy community united by their shared love of classic Hollywood. Two such are John McElwee (left) of

Greenbriar Picture Shows and Richard M. Roberts. Both are major contributors to Cinevent’s program notes, and both were there this year selling their recently published books: John’s

Showmen, Sell It Hot!: Movies as Merchandise in Golden Era Hollywood; and Richard’s

Past Humor, Present Laughter: Musings on the Comedy Film Industry 1910-1945, Vol. One: Hal Roach. I’ll have more to say about both books next time.

Upstaging The Sea Beast, and just about everything else shown at Cinevent this year, was a real discovery, an absolute bolt out of nowhere, a picture almost nobody had ever heard of. It was The Canadian (1926), directed by none other than William Beaudine. Yes, the notorious “One-Shot” Beaudine, who cranked out some 368 features, shorts and TV episodes over his 53-year career — including the sexploitation “documentary” Mom and Dad (’45) and, towards the end of his run, the camp titles Billy the Kid Vs. Dracula and Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter (both ’66). But back in the ’20s, Beaudine was a director to reckon with, and The Canadian shows why. It’s a simple story: Young Englishwoman Nora Marsh (Mona Palma) is left penniless at the death of the aunt she’s been living with, and has no choice but to emigrate to Canada, where her brother is a struggling farmer on the frontier of western Ontario. Pampered, stuck-up and generally useless, Nora clashes with her brother’s no-nonsense wife, until at length the wife lays down an either-she-goes-or-I-go ultimatum. Nora impulsively marries Frank Taylor, a neighboring farmer (Thomas Meighan), and the rest of the picture tells how this prissy little snob learns to carry her weight in her new household, where she and her stranger/husband slowly grow to love each other.

Upstaging The Sea Beast, and just about everything else shown at Cinevent this year, was a real discovery, an absolute bolt out of nowhere, a picture almost nobody had ever heard of. It was The Canadian (1926), directed by none other than William Beaudine. Yes, the notorious “One-Shot” Beaudine, who cranked out some 368 features, shorts and TV episodes over his 53-year career — including the sexploitation “documentary” Mom and Dad (’45) and, towards the end of his run, the camp titles Billy the Kid Vs. Dracula and Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter (both ’66). But back in the ’20s, Beaudine was a director to reckon with, and The Canadian shows why. It’s a simple story: Young Englishwoman Nora Marsh (Mona Palma) is left penniless at the death of the aunt she’s been living with, and has no choice but to emigrate to Canada, where her brother is a struggling farmer on the frontier of western Ontario. Pampered, stuck-up and generally useless, Nora clashes with her brother’s no-nonsense wife, until at length the wife lays down an either-she-goes-or-I-go ultimatum. Nora impulsively marries Frank Taylor, a neighboring farmer (Thomas Meighan), and the rest of the picture tells how this prissy little snob learns to carry her weight in her new household, where she and her stranger/husband slowly grow to love each other.

Samantha: Don't feel too bad; I almost skipped The Canadian myself. Who knew? (I have to thank Richard Roberts for piquing my interest with his program notes.) It was great seeing you again in Columbus, and I look forward to seeing you yet again next year.

Now I'm bummed that I didn't see The Canadian. But it is hard sitting for so long, especially know there are so many people there to talk to, and so much memorabilia to see.

Silver: It's Cinevent that provides the public service; I'm just the messenger. I hope you'll consider joining us next year; if you do, as I told Karen, be sure to look me up and say hi.

I read your posts out of order, but now that I see the great films that are offered at Cinevent, I'm even more chagrined that I didn't know about this.

You see what a valuable public service you're offering here?